בבא בתרא כז

בֵּית סְאָה בִּשְׁבִילָן. כַּמָּה הָווּ לְהוּ – תְּרֵי אַלְפֵי וַחֲמֵשׁ מְאָה גַּרְמִידֵי; לְכׇל חַד כַּמָּה מָטֵי לֵיהּ – תַּמְנֵי מְאָה וּתְלָתִין וּתְלָתָא וְתִילְתָּא; אַכַּתִּי נְפִישִׁי לֵיהּ דְּעוּלָּא! לָא דָּק.

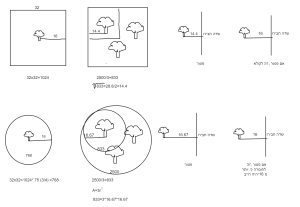

beit se’a for their sake. How much is that area in cubits? It is 2,500 square cubits. And how much area is that for each of the trees? It is 833⅓. Still, Ulla‘s amount is greater than this. The Gemara answers: Ulla was not precise in this matter.

אֵימוֹר דְּאָמְרִינַן לָא דָּק – לְחוּמְרָא; לְקוּלָּא – לָא דָּק מִי אָמְרִינַן?!

The Gemara asks: One can say that we say that a Sage was not precise in his measurements when his ruling leads to a stringency; but do we say that he was not precise if his measurements lead to a leniency? According to the previous explanation, Ulla exempts the owner of a tree from first fruits even in a case where his tree does not in fact draw nourishment from his neighbor’s field.

מִי סָבְרַתְּ בְּרִיבּוּעָא קָא אָמְרִינַן?! בְּעִיגּוּלָא קָא אָמְרִינַן!

The Gemara answers: Do you maintain that we say the roots extend that far in a square, i.e., one measures sixteen cubits to each side of the tree? Not so; we say this with regard to a circle, that is, the roots extend in a circle surrounding the tree, as the area of a circle is smaller than that of the square circumscribing it.

מִכְּדֵי כַּמָּה מְרוּבָּע יוֹתֵר עַל הָעִיגּוּל – רְבִיעַ; פָּשׁוּ לְהוּ שְׁבַע מְאָה וְשִׁתִּין וּתְמָנְיָא; אַכַּתִּי פָּשׁ לֵיהּ פַּלְגָא דְאַמְּתָא! הַיְינוּ דְּלָא דָּק – וּלְחוּמְרָא לָא דָּק.

The Gemara asks: Now, by how much is the area of a square greater than the area of a circle with a diameter the length of the side of that square? It is greater by one-quarter of the area of the circle. If so, 768 square cubits, three-quarters of 1,024, remain for each tree, but there still remains half a cubit more based on the mishna’s calculation. In other words, the measurement would be more accurate if a tree is considered to draw nourishment from a distance of sixteen and a half cubits on each side. The Gemara answers: This is why we said that Ulla was not precise, and he was not precise in a manner that leads to a stringency, as one brings first fruits even from a tree that stands just sixteen cubits from the boundary, rather than 16½.

תָּא שְׁמַע: הַקּוֹנֶה אִילָן וְקַרְקָעוֹ – מֵבִיא וְקוֹרֵא. מַאי, לָאו כׇּל שֶׁהוּא? לֹא; שֵׁשׁ עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה.

The Gemara cites a proof against the opinion of Ulla. Come and hear the following mishna (Bikkurim 1:11): One who buys a tree and its land brings first fruits and recites the requisite Torah verses (Deuteronomy 26:5–11) over them. What, is it not referring to a case where one buys any amount of land with the tree? The Gemara rejects this claim: No; it is referring to a case where one buys sixteen cubits of land around the tree.

תָּא שְׁמַע: קָנָה שְׁנֵי אִילָנוֹת בְּתוֹךְ שֶׁל חֲבֵירוֹ – מֵבִיא וְאֵינוֹ קוֹרֵא. הָא שְׁלֹשָׁה – מֵבִיא וְקוֹרֵא; מַאי, לָאו כׇּל שֶׁהוּא? לָא; הָכָא נָמֵי שֵׁשׁ עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה.

The Gemara suggests: Come and hear an additional proof from another mishna (Bikkurim 1:6): If one bought two trees in the field of another, he brings first fruits and does not recite the verses, because the land does not belong to him. It may be inferred from here that if he bought three trees he does bring first fruits and recite the verses. What, is it not referring to a case where one buys any amount of land with the trees? The Gemara rejects this claim as well: No; here too it is referring to a case where he acquires sixteen cubits of land around the trees.

תָּא שְׁמַע, רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אוֹמֵר: קַרְקַע כׇּל שֶׁהוּא – חַיָּיב בַּפֵּאָה וּבַבִּכּוּרִים, וְכוֹתְבִין עָלָיו פְּרוֹזְבּוּל,

The Gemara suggests: Come and hear a proof from a mishna (Pe’a 3:6). Rabbi Akiva says: The owner of land of any size is obligated in pe’a and in first fruits, and a lender can write a document that prevents the Sabbatical Year from abrogating an outstanding debt [prosbol] for this land, so that loans he provided will not be canceled at the close of the Sabbatical Year,

וְנִקְנִין עִמָּהּ נְכָסִים שֶׁאֵין לָהֶם אַחְרָיוּת! הָכָא בְּמַאי עָסְקִינַן – בְּחִיטֵּי.

and he can acquire property that does not serve as a guarantee, i.e., movable property, along with it. There are specific modes of acquisition for movable property, but if one is acquiring any amount of land at the same time as the movable property, the mode of acquisition employed to acquire the land suffices for the acquisition of the movable property as well. Apparently, any amount of land is subject to first fruits, whereas according to Ulla a tree acquired with less than sixteen cubits of land surrounding it draws nourishment from the land surrounding it and is exempt from first fruits. The Gemara rejects this: With what are we dealing here? We are dealing with wheat, which is subject to the halakhot of first fruits and requires very little land to nourish it.

דַּיְקָא נָמֵי, דְּקָתָנֵי: כׇּל שֶׁהוּא. שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ.

The Gemara comments that the language of the mishna is also precise, as it teaches: Land of any size, which indicates even a miniscule amount, and all normal trees certainly require more land than that. The Gemara affirms: Learn from it that it is so.

תָּא שְׁמַע: אִילָן – מִקְצָתוֹ בָּאָרֶץ וּמִקְצָתוֹ בְּחוּץ לָאָרֶץ – טֶבֶל וְחוּלִּין מְעוֹרָבִין זֶה בָּזֶה, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי.

The Gemara further suggests: Come and hear a proof from a baraita (Tosefta, Ma’asrot 2:22): If there is a tree, part of which is in Eretz Yisrael and part of which is outside of Eretz Yisrael, it is considered as though untithed produce, i.e., produce that is subject to the halakhot of terumot and tithes, and non-sacred produce, i.e., produce that is exempt from the halakhot of terumot and tithes, are mixed together in each one of this tree’s fruits. This is the statement of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi.

רַבָּן שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל אוֹמֵר: הַגָּדֵל בְּחִיּוּב – חַיָּיב, הַגָּדֵל בִּפְטוּר – פָּטוּר.

Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel says: With regard to the fruits in the part of the tree that is growing in a place where there is an obligation to separate tithes, i.e., in Eretz Yisrael, the owner is obligated to separate tithes. With regard to the fruits that are growing in a place where there is an exemption from separating tithes, i.e., outside of Eretz Yisrael, the owner is exempt.

עַד כָּאן לָא פְּלִיגִי, אֶלָּא דְּמָר סָבַר: יֵשׁ בְּרֵירָה, וּמַר סָבַר: אֵין בְּרֵירָה;

The Gemara comments: They disagree only in that one Sage, Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, holds that there is retroactive designation, and therefore it is assumed that the nourishment drawn from Eretz Yisrael sustained the fruit that grew on that side of the tree, and the nourishment drawn from outside Eretz Yisrael sustained the fruit that grew there. And one Sage, Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, holds that there is no retroactive designation, and the fruit is considered mixed.

אֲבָל גָּדֵל בִּפְטוּר – דִּבְרֵי הַכֹּל פָּטוּר!

But if the tree grew entirely in a place where there is an exemption from separating tithes, i.e., outside Eretz Yisrael, all agree that the owner is exempt, even though the tree might have roots within sixteen cubits of Eretz Yisrael and draw nourishment from there. This presents a difficulty for the opinion of Ulla, as he claims that the place from where a tree draws its nourishment is decisive with regard to first fruits.

הָכָא בְּמַאי עָסְקִינַן – דְּמַפְסִיק צוּנְמָא. אִי הָכִי, מַאי טַעְמֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי? דְּהָדְרִי עׇרְבִי.

The Gemara answers: With what are we dealing here? We are dealing with a case where a rock divides the roots up to the trunk, and therefore it is possible to distinguish between the parts of the tree that draw nutrients from Eretz Yisrael and the parts that draw nutrients from outside of Eretz Yisrael. The Gemara asks: If so, what is the reasoning of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi? Why does he view the fruits as being a mixture? The Gemara answers: He holds that although there is a division between the roots, they cannot be distinguished from one another, as they then become mixed in the body of the tree.

וּבְמַאי קָא מִיפַּלְגִי? מָר סָבַר: אַוֵּירָא מְבַלְבֵּל, וּמָר סָבַר: הַאי לְחוֹדֵיהּ קָאֵי וְהַאי לְחוֹדֵיהּ קָאֵי.

The Gemara asks: And with regard to what principle do they disagree? The Gemara answers: One Sage, Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, holds: The air above the ground mixes the nutrients, and one Sage, Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, holds: This part of the tree stands alone and this part of the tree stands alone. From the roots up to the branches, it is as if the tree were cut along the line of the border.

וְשֵׁשׁ עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה – וְתוּ לָא? וְהָא תְּנַן: מַרְחִיקִין אֶת הָאִילָן מִן הַבּוֹר, עֶשְׂרִים וְחָמֵשׁ אַמָּה! אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: מֵיזָל – טוּבָא אָזְלִי, אַכְחוֹשֵׁי לָא מַכְחֲשִׁי אֶלָּא עַד שֵׁשׁ עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה, טְפֵי לָא מַכְחֲשִׁי.

The Gemara raises a difficulty against Ulla’s opinion from a different perspective: And do roots extend sixteen cubits and no more? Didn’t we learn in a mishna (25b): One must distance a tree twenty-five cubits from a cistern? This indicates that tree roots reach more than sixteen cubits. Abaye said: The roots extend farther, but they weaken the ground only up to sixteen cubits; with regard to an area any more distant than that, they do not weaken the ground.

כִּי אֲתָא רַב דִּימִי אָמַר, בְּעָא מִינֵּיהּ רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ מֵרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: אִילָן הַסָּמוּךְ לַמֶּיצֶר בְּתוֹךְ שֵׁשׁ עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה, מַהוּ? אֲמַר לֵיהּ: גַּזְלָן הוּא, וְאֵין מְבִיאִין מִמֶּנּוּ בִּכּוּרִים.

Concerning this matter the Gemara relates that when Rav Dimi came from Eretz Yisrael he said: Reish Lakish raised a dilemma before Rabbi Yoḥanan: With regard to a tree that is within sixteen cubits of a boundary, what is the halakha? Rabbi Yoḥanan said to him: The owner is a robber, and one does not bring first fruits from it.

כִּי אֲתָא רָבִין אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: אֶחָד אִילָן הַסָּמוּךְ לַמֶּיצֶר, וְאֶחָד אִילָן הַנּוֹטֶה – מֵבִיא וְקוֹרֵא; שֶׁעַל מְנָת כֵּן הִנְחִיל יְהוֹשֻׁעַ לְיִשְׂרָאֵל אֶת הָאָרֶץ.

By contrast, when Ravin came from Eretz Yisrael, he related that Rabbi Yoḥanan says: Both in the case of a tree that is close to a boundary and a tree that leans into a neighbor’s yard, one brings first fruits and recites the verses, as it was on this condition that Joshua apportioned Eretz Yisrael to the Jewish people, i.e., that they would not be particular about such matters.

מַתְנִי׳ אִילָן שֶׁהוּא נוֹטֶה לִשְׂדֵה חֲבֵירוֹ – קוֹצֵץ מְלֹא הַמַּרְדֵּעַ, עַל גַּבֵּי הַמַּחֲרֵישָׁה. וּבֶחָרוּב וּבַשִּׁקְמָה – כְּנֶגֶד הַמִּשְׁקוֹלֶת. בֵּית הַשְּׁלָחִין – כׇּל הָאִילָן כְּנֶגֶד הַמִּשְׁקוֹלֶת. אַבָּא שָׁאוּל אוֹמֵר: כׇּל אִילַן סְרָק כְּנֶגֶד הַמִּשְׁקוֹלֶת.

MISHNA: With regard to a tree that leans into the field of another, the neighbor may cut the branches to the height of an ox goad raised over the plow, in places where the land is to be plowed, so that the branches do not impede the use of the plow. And in the case of a carob tree and the case of a sycamore tree, whose abundance of branches cast shade that is harmful to plants, all the branches overhanging one’s property may be removed along the plumb line, i.e., along a line perpendicular to the boundary separating the fields. And if the neighbor’s field is an irrigated field, all branches of the tree are removed along the plumb line. Abba Shaul says: All barren trees are cut along the plumb line.

גְּמָ׳ אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: אַבָּא שָׁאוּל – אַרֵישָׁא קָאֵי, אוֹ אַסֵּיפָא קָאֵי?

GEMARA: A dilemma was raised before them: Is Abba Shaul referring to the first clause of the mishna, which states that a tree extending into a neighbor’s field is cut only to the height of an ox goad, and Abba Shaul maintains that barren trees have the same halakha as carob and sycamore trees in that they are cut along the plumb line? Or is he referring to the latter clause, which discusses an irrigated field, and he permits cutting only barren trees along the plumb line, but not fruit trees?

תָּא שְׁמַע, דְּתַנְיָא: בֵּית הַשְּׁלָחִין – אַבָּא שָׁאוּל אוֹמֵר: כׇּל הָאִילָן כְּנֶגֶד הַמִּשְׁקוֹלֶת, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁהַצֵּל רַע לְבֵית הַשְּׁלָחִין. שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ: אַרֵישָׁא קָאֵי! שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ.

The Gemara answers: Come and hear a resolution to this dilemma, as it is taught in a baraita: With regard to an irrigated field, Abba Shaul says: All types of trees are cut along the plumb line, because the shade is harmful to an irrigated field. This shows that he does not dispute the halakha of the latter clause. Learn from it that he is referring to the first clause of the mishna. The Gemara affirms: Learn from it that it is so.

אָמַר רַב אָשֵׁי: מַתְנִיתִין נָמֵי דַּיְקָא, דְּקָתָנֵי: ״כׇּל אִילַן סְרָק״. אִי אָמְרַתְּ בִּשְׁלָמָא אַרֵישָׁא קָאֵי – הַיְינוּ דְּקָתָנֵי כׇּל אִילָן; אֶלָּא אִי אָמְרַתְּ אַסֵּיפָא קָאֵי, אִילַן סְרָק מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ?! אֶלָּא לָאו שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ אַרֵישָׁא קָאֵי? שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ.

Rav Ashi said that the wording of the mishna is also precise, as it teaches: All barren trees. Granted, if you say that Abba Shaul is referring to the first clause of the mishna, this is the reason that Abba Shaul teaches: All barren trees. But if you say that he is referring to the latter clause, he should have said simply: Barren trees, as the first tanna permits one to cut down any type of tree. Rather, isn’t it correct to conclude from it that he is referring to the first clause? The Gemara affirms: Learn from it that it is so.

מַתְנִי׳ אִילָן שֶׁהוּא נוֹטֶה לִרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים, קוֹצֵץ כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּהֵא גָּמָל עוֹבֵר – וְרוֹכְבוֹ. רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: גָּמָל טָעוּן פִּשְׁתָּן אוֹ חֲבִילֵי זְמוֹרוֹת. רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: כׇּל הָאִילָן כְּנֶגֶד הַמִּשְׁקוֹלֶת, מִפְּנֵי הַטּוּמְאָה.

MISHNA: With regard to a tree that extends into the public domain, one cuts its branches so that a camel can pass beneath the tree with its rider sitting on it. Rabbi Yehuda says: One cuts enough branches that a camel loaded with flax or bundles of branches can pass beneath it. Rabbi Shimon says: One cuts all branches of the tree that extend into the public domain along the plumb line, so that they do not hang over the public area at all, due to ritual impurity.

גְּמָ׳ מַאן תְּנָא דְּבִנְזָקִין – בָּתַר אוּמְדָּנָא דְּהַשְׁתָּא אָזְלִינַן?

GEMARA: The Gemara asks: Who is the tanna who taught that with regard to damage one follows the current assessment, and future damage is not taken into account? The mishna states that the tree’s branches are cut to the height of a camel and its rider or load but no more, despite the fact that they will certainly grow again.

אָמַר רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ: בְּמַחֲלוֹקֶת שְׁנוּיָה, וְרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר הִיא – דִּתְנַן: אֵין עוֹשִׂין חָלָל תַּחַת רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים – בּוֹרוֹת, שִׁיחִין וּמְעָרוֹת. רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר מַתִּיר, בִּכְדֵי שֶׁתְּהֵא עֲגָלָה מְהַלֶּכֶת – וּטְעוּנַהּ אֲבָנִים.

Reish Lakish says: This halakha is taught as a dispute, and it is the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. As we learned in a mishna (60a): One may not make an empty space beneath the public domain by digging pits, ditches, or caves. Rabbi Eliezer permits one to dig a pit if it is subsequently covered with material strong enough that a wagon loaded with stones can travel on it without it collapsing. If the cover can withstand such weight when the pit is dug, it is permitted, despite the fact that the cover might eventually rot.

רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר: אֲפִילּוּ תֵּימָא רַבָּנַן, הָתָם – זִימְנִין דְּמַפְחִית וְלָאו אַדַּעְתֵּיהּ, אֲבָל הָכָא – קַמָּא קַמָּא קָא קְיִיץ לֵיהּ.

Rabbi Yoḥanan said: You may even say that the mishna here represents the opinion of the Rabbis, who prohibit one from digging beneath the public domain under any circumstances. The difference is that there, the cover will occasionally deteriorate, and as this matter is not on his mind it will cause damage. But here, as each branch grows he cuts it off. Since the potential cause of damage is visible, there is no concern that it might be neglected.

רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: גָּמָל טָעוּן פִּשְׁתָּן אוֹ חֲבִילֵי זְמוֹרוֹת. אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: שִׁיעוּרָא דְרַבִּי יְהוּדָה נְפִישׁ, אוֹ דִּלְמָא שִׁיעוּרָא דְרַבָּנַן נְפִישׁ?

§ The mishna teaches that if the branches of a tree extend into the public domain, one may cut them to allow a camel and its rider to pass underneath; Rabbi Yehuda says: One cuts enough branches that a camel loaded with flax or bundles of branches can pass beneath it. A dilemma was raised before the Sages: Is Rabbi Yehuda’s measure greater, or is perhaps the Rabbis’ measure greater? Which reaches a greater height, a camel and rider or a camel loaded with flax?

פְּשִׁיטָא דְּשִׁיעוּרָא דְרַבָּנַן נְפִישׁ! דְּאִי סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ שִׁיעוּרָא דְרַבִּי יְהוּדָה נְפִישׁ, רַבָּנַן – בְּשִׁיעוּרָא דְרַבִּי יְהוּדָה הֵיכִי עָבְדִי? וְאֶלָּא מַאי, שִׁיעוּרָא דְרַבָּנַן נְפִישׁ? רַבִּי יְהוּדָה – בְּשִׁיעוּרָא דְּרַבָּנַן מַאי עָבֵיד? אֶפְשָׁר דִּגְחִין וְחָלֵיף תּוּתֵיהּ.

The Gemara answers: It is obvious that the Rabbis’ measure is greater, as, if it enters your mind that Rabbi Yehuda’s measure is greater, how would the Rabbis act in the circumstance of Rabbi Yehuda’s measure? It is clear that a camel will have to pass beneath the tree with a burden, and it would not be able to do so. The Gemara expresses surprise at this claim: Rather, what then would you say? That the Rabbis’ measure is greater? If so, how would Rabbi Yehuda act in the circumstance of the Rabbis’ measure? It is also clear that a camel will have to pass there with its rider. The Gemara answers: It is possible for the rider to bend over and to pass underneath the branches.

רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: כׇּל הָאִילָן כְּנֶגֶד הַמִּשְׁקוֹלֶת, מִפְּנֵי הַטּוּמְאָה. תָּנָא: מִפְּנֵי אֹהֶל הַטּוּמְאָה. פְּשִׁיטָא, ״מִפְּנֵי הַטּוּמְאָה״ תְּנַן!

§ The mishna teaches that Rabbi Shimon says: One cuts all branches of the tree that extend into the public domain along the plumb line, due to ritual impurity. The Gemara explains: A tanna taught in a baraita that this is due to ritual impurity imparted in a tent. Branches over a corpse might create a tent, thereby transferring impurity to whatever is beneath the branches, rendering impure those passing under the tree in the public domain. The Gemara expresses surprise at this statement: It is obvious that this is the reason. We already learned that it is due to ritual impurity. How else could ritual impurity be transferred through branches other than by means of a tent?

אִי מִמַּתְנִיתִין, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא: דִּלְמָא מַיְיתֵי עוֹרֵב טוּמְאָה וְשָׁדֵי הָתָם, וְסַגְיָא בְּדַחְלוּלִי בְּעָלְמָא; קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן:

The Gemara answers: If this is learned from the mishna alone, I would say that the concern is that perhaps a crow might bring a source of impurity and perch on the tree’s branches and throw it there. And if that were the only concern, a mere scarecrow [bedaḥlulei] would be sufficient to frighten the crows away and prevent that type of impurity. Therefore, the tanna of the baraita teaches us that the concern is due to impurity imparted in a tent.

הַדְרָן עֲלָךְ לָא יַחְפּוֹר