Today’s daf is sponsored in honor of Rabbanit Dasi Fruchter and the South Philadelphia Shtiebel on their siyum of Mesechet Yoma! “We are so inspired by your learning and leadership. Sending so much love your way!! Love, Chayim and Rena Fruchter, Temim Fruchter, Yoshie Fruchter and Leah Koenig, Ora Fruchter and Bradford Jordan, Hannah Heller, Elliot Heller, Amy Supraner and David Fruchter, Debbie Robinson, Yehudit and Sam Daitch, Yechiel Robinson, Sarah Robinson, Rabbi Nissan Antine, Ariel Hart, Maharat Ruth Balinsky Friedman, Rabbi Steven Exler.”

Yoma 87

Share this shiur:

This month’s learning is dedicated to the refuah shleima of our dear friend, Phyllis Hecht, גיטל פעשא בת מאשה רחל by all her many friends who love and admire her. Phyllis’ emuna, strength, and positivity are an inspiration.

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Today’s daily daf tools:

This month’s learning is dedicated to the refuah shleima of our dear friend, Phyllis Hecht, גיטל פעשא בת מאשה רחל by all her many friends who love and admire her. Phyllis’ emuna, strength, and positivity are an inspiration.

Today’s daily daf tools:

Delve Deeper

Broaden your understanding of the topics on this daf with classes and podcasts from top women Talmud scholars.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

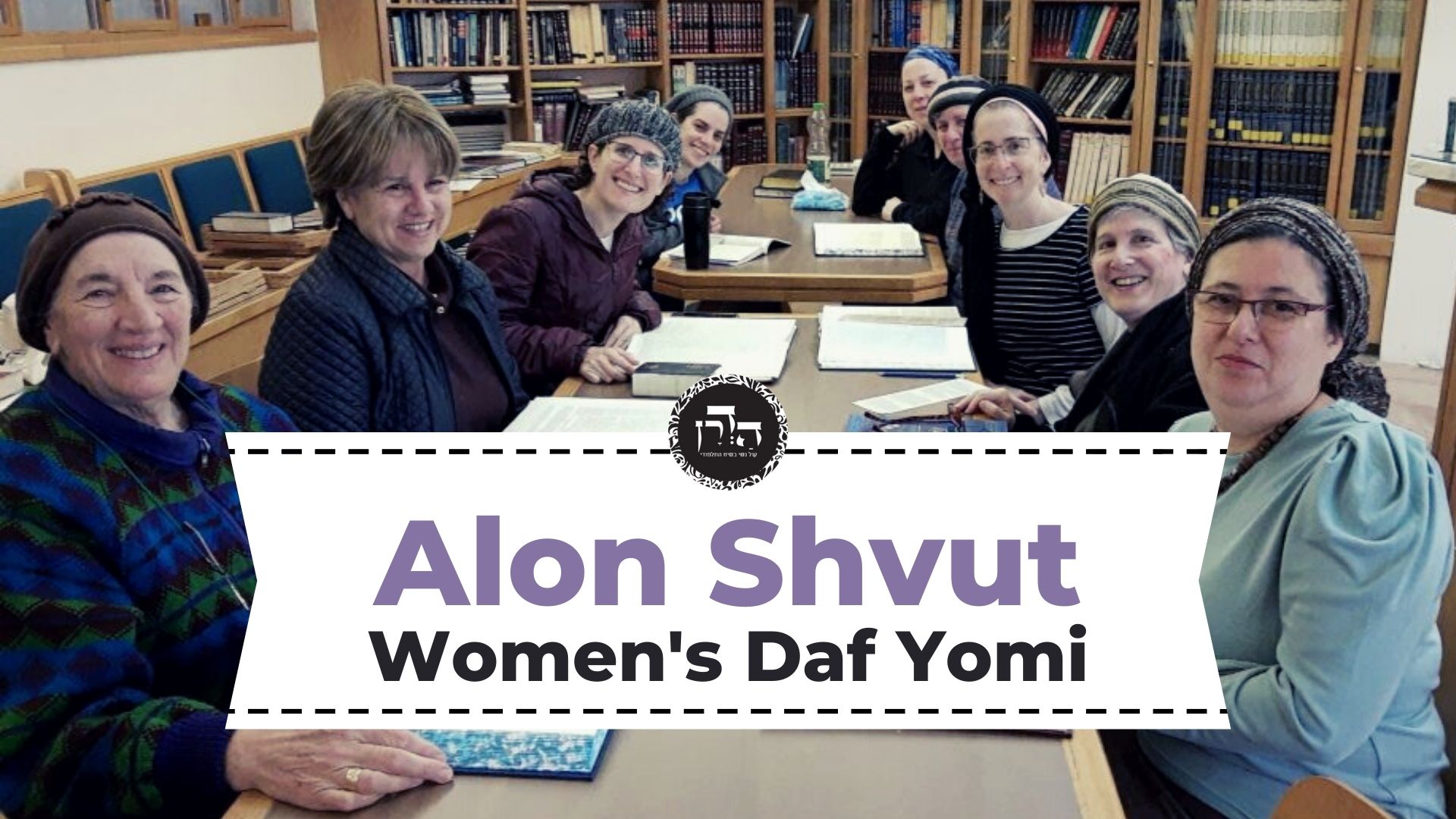

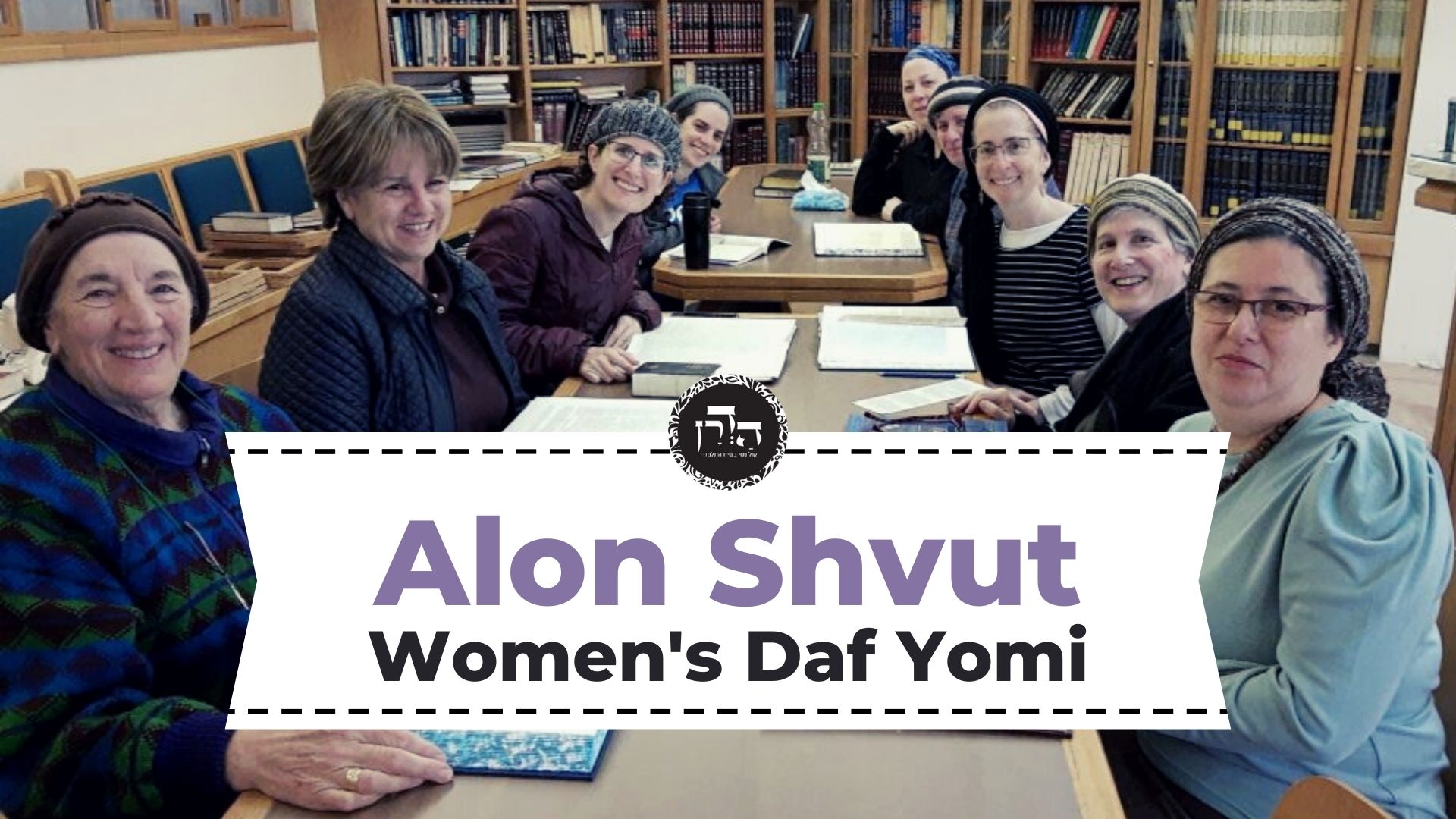

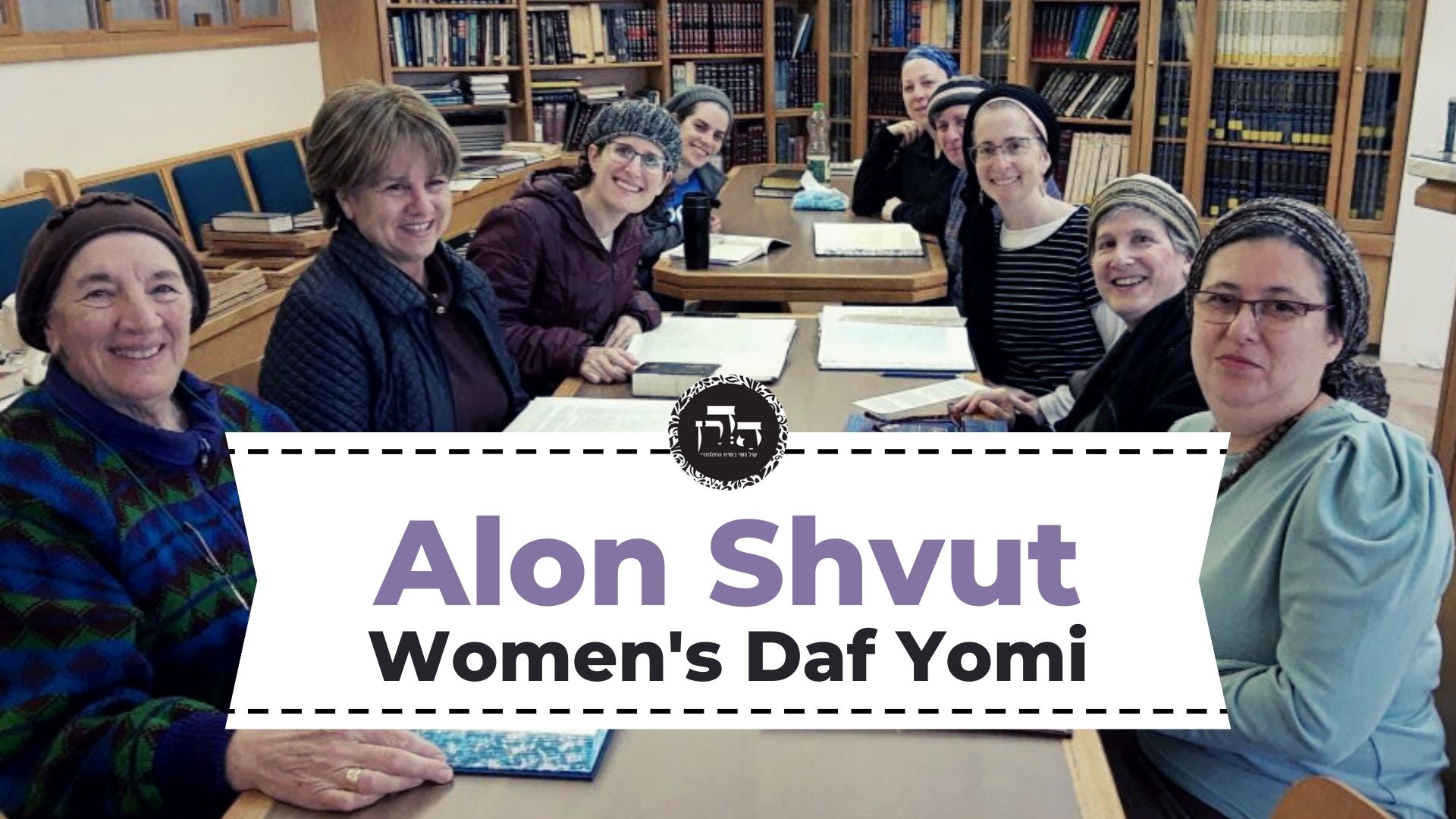

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Yoma 87

בִּצְבוּ נַפְשֵׁיהּ לִקְטָלָא נָפֵיק, וּצְבוּ בֵּיתֵיהּ לֵית הוּא עָבֵיד, וְרֵיקָן לְבֵיתֵיהּ אָזֵיל, וּלְוַאי שֶׁתְּהֵא בִּיאָה כִּיצִיאָה. וְכִי הָוֵי חָזֵי אַמְבּוּהָא אַבָּתְרֵיהּ, אָמַר: ״אִם יַעֲלֶה לַשָּׁמַיִם שִׂיאוֹ וְרֹאשׁוֹ לָעָב יַגִּיעַ. כְּגֶלֲלוֹ לָנֶצַח יֹאבֵד רוֹאָיו יֹאמְרוּ אַיּוֹ״. רַב זוּטְרָא, כִּי הֲווֹ מְכַתְּפִי לֵיהּ בְּשַׁבְּתָא דְרִיגְלָא, הֲוָה אָמַר: ״כִּי לֹא לְעוֹלָם חֹסֶן וְאִם נֵזֶר לְדוֹר וָדוֹר״.

Of his own will, he goes to die; and he does not fulfill the will of his household, and he goes empty-handed to his household; and if only his entrance would be like his exit. And when he saw a line of people [ambuha] following after him out of respect for him, he said: “Though his excellency ascends to the heavens, and his head reaches to the clouds, yet he shall perish forever like his own dung; they who have seen him will say: Where is he?” (Job 20:6–7). This teaches that when one achieves power, it can lead to his downfall. When they would carry Rav Zutra on their shoulders during the Shabbat of the Festival when he taught, he would recite the following to avoid becoming arrogant: “For power is not forever, and does the crown endure for all generations?” (Proverbs 27:24).

״שְׂאֵת פְּנֵי רָשָׁע לֹא טוֹב״ — לֹא טוֹב לָהֶם לָרְשָׁעִים שֶׁנּוֹשְׂאִין לָהֶם פָּנִים בָּעוֹלָם הַזֶּה. לֹא טוֹב לוֹ לְאַחְאָב שֶׁנָּשְׂאוּ לוֹ פָּנִים בָּעוֹלָם הַזֶּה, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״יַעַן כִּי נִכְנַע (אַחְאָב מִלְּפָנָי) לֹא אָבִיא הָרָעָה בְּיָמָיו״.

§ It was further taught: “It is not good to respect the person of the wicked” (Proverbs 18:5), meaning, it is not good for wicked people when they are respected in this world and are not punished for their sins. For example, it was not good for Ahab to be respected in this world, as it is stated: “Because he humbled himself before Me, I will not bring the evil in his days” (I Kings 21:29), and Ahab thereby lost his share in the World-to-Come.

״לְהַטּוֹת צַדִּיק בַּמִּשְׁפָּט״ — טוֹב לָהֶם לַצַּדִּיקִים שֶׁאֵין נוֹשְׂאִין לָהֶם פָּנִים בָּעוֹלָם הַזֶּה. טוֹב לוֹ לְמֹשֶׁה שֶׁלֹּא נָשְׂאוּ לוֹ פָּנִים בָּעוֹלָם הַזֶּה, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״יַעַן לֹא הֶאֱמַנְתֶּם בִּי לְהַקְדִּישֵׁנִי״, הָא אִילּוּ הֶאֱמַנְתֶּם בִּי — עֲדַיִין לֹא הִגִּיעַ זְמַנָּם לִיפָּטֵר מִן הָעוֹלָם.

The opposite is also true. The complete verse states: “It is not good to respect the person of the wicked, to turn aside the righteous in judgment” (Proverbs 18:5), meaning: It is good for the righteous when they are not respected in this world and are punished in this world for their sins. For example, it was good for Moses that he was not respected in this world, as it is stated: “Because you did not believe in Me, to sanctify Me” (Numbers 20:12). The Gemara analyzes this: Had you believed in Me, your time still would not have come to depart the world.

אַשְׁרֵיהֶם לַצַּדִּיקִים, לֹא דַּיָּין שֶׁהֵן זוֹכִין, אֶלָּא שֶׁמְּזַכִּין לִבְנֵיהֶם וְלִבְנֵי בְנֵיהֶם עַד סוֹף כׇּל הַדּוֹרוֹת. שֶׁכַּמָּה בָּנִים הָיוּ לוֹ לְאַהֲרֹן שֶׁרְאוּיִין לִישָּׂרֵף כְּנָדָב וַאֲבִיהוּא, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״הַנּוֹתָרִים״, אֶלָּא שֶׁעָמַד לָהֶם זְכוּת אֲבִיהֶם.

They said: Fortunate are the righteous because not only do they accumulate merit for themselves, but they accumulate merit for their children and their children’s children until the end of all generations; as there were several sons of Aaron who essentially deserved to be burned like Nadav and Avihu, as it is stated: “The sons of Aaron who were left” (Leviticus 10:16), implying that others were left as well although they deserved to be burned with their brothers. But the merit of their father protected them, and they and their descendants were priests for all time.

אוֹי לָהֶם לָרְשָׁעִים, לֹא דַּיָּין שֶׁמְּחַיְּיבִין עַצְמָן, אֶלָּא שֶׁמְּחַיְּיבִין לִבְנֵיהֶם וְלִבְנֵי בְנֵיהֶם עַד סוֹף כׇּל הַדּוֹרוֹת. הַרְבֵּה בָּנִים הָיוּ לוֹ לִכְנַעַן שֶׁרְאוּיִין לִיסָּמֵךְ כְּטָבִי עַבְדּוֹ שֶׁל רַבָּן גַּמְלִיאֵל, אֶלָּא שֶׁחוֹבַת אֲבִיהֶם גָּרְמָה לָהֶן.

On the other hand: Woe to the wicked, as not only do they render themselves liable, but they also render their children and children’s children liable until the end of all generations. For example, Canaan had many children who deserved to be ordained as rabbis and instructors of the public due to their great stature in Torah study, like Tavi, the servant of Rabban Gamliel, who was famous for his wisdom; but their father’s liability caused them to remain as slaves.

כׇּל הַמְזַכֶּה אֶת הָרַבִּים — אֵין חֵטְא בָּא עַל יָדוֹ, וְכׇל הַמַּחְטִיא אֶת הָרַבִּים — כִּמְעַט אֵין מַסְפִּיקִין בְּיָדוֹ לַעֲשׂוֹת תְּשׁוּבָה. כׇּל הַמְזַכֶּה אֶת הָרַבִּים — אֵין חֵטְא בָּא עַל יָדוֹ, מַאי טַעְמָא? כְּדֵי שֶׁלֹּא יְהֵא הוּא בְּגֵיהִנָּם וְתַלְמִידָיו בְּגַן עֵדֶן, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״כִּי לֹא תַעֲזוֹב נַפְשִׁי לִשְׁאוֹל לֹא תִתֵּן חֲסִידְךָ לִרְאוֹת שָׁחַת״. וְכׇל הַמַּחְטִיא אֶת הָרַבִּים — אֵין מַסְפִּיקִין בְּיָדוֹ לַעֲשׂוֹת תְּשׁוּבָה, שֶׁלֹּא יְהֵא הוּא בְּגַן עֵדֶן וְתַלְמִידָיו בְּגֵיהִנָּם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״אָדָם עָשׁוּק בְּדַם נָפֶשׁ עַד בּוֹר יָנוּס אַל יִתְמְכוּ בוֹ״.

Furthermore: Whoever accumulates merit for the public will not have sin come to his hand, and God protects him from failing; but whoever causes the public to sin has almost no ability to repent. The Gemara explains: What is the reason that whoever accumulates merit for the public will not have sin come to his hand? It is so that he will not be in Gehenna while his students are in the Garden of Eden, as it is stated: “For You will not abandon my soul to the nether-world; neither will You suffer Your godly one to see the pit” (Psalms 16:10). On the other hand, whoever causes the public to sin has almost no ability to repent, so that he will not be in the Garden of Eden while his students are in Gehenna, as it is stated: “A man who is laden with the blood of any person shall hasten his steps to the pit; none will support him” (Proverbs 28:17). Since he oppressed others and caused them to sin, he shall have no escape.

הָאוֹמֵר אֶחֱטָא וְאָשׁוּב אֶחֱטָא וְאָשׁוּב. לְמָה לִי לְמֵימַר ״אֶחֱטָא וְאָשׁוּב, אֶחֱטָא וְאָשׁוּב״ תְּרֵי זִימְנֵי? כִּדְרַב הוּנָא אָמַר רַב. דְּאָמַר רַב הוּנָא אָמַר רַב: כֵּיוָן שֶׁעָבַר אָדָם עֲבֵירָה וְשָׁנָה בָּהּ — הוּתְּרָה לוֹ. הוּתְּרָה לוֹ סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ?! אֶלָּא: נַעֲשֵׂית לוֹ כְּהֶיתֵּר.

§ The Gemara returns to interpreting the mishna. It states there that one who says: I will sin and I will repent, I will sin and I will repent, is not given the opportunity to repent.The Gemara asks: Why do I need the mishna to say twice: I will sin and I will repent, I will sin and repent? The Gemara explains that this is in accordance with that which Rav Huna said that Rav said, as Rav Huna said that Rav said: Once a person commits a transgression and repeats it, it becomes permitted to him. The Gemara is surprised at this: Can it enter your mind that it becomes permitted to him? Rather, say that it becomes to him as though it were permitted. Consequently, the sinner who repeats his sin has difficulty abandoning his sin, and the repetition of his sin is reflected in the repetition of the phrase.

אֶחֱטָא וְיוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים מְכַפֵּר — אֵין יוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים מְכַפֵּר. לֵימָא מַתְנִיתִין דְּלָא כְּרַבִּי. דְּתַנְיָא, רַבִּי אוֹמֵר: עַל כׇּל עֲבֵירוֹת שֶׁבַּתּוֹרָה, בֵּין עָשָׂה תְּשׁוּבָה בֵּין לֹא עָשָׂה תְּשׁוּבָה — יוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים מְכַפֵּר! אֲפִילּוּ תֵּימָא רַבִּי, אַגַּב שָׁאנֵי.

It is stated in the mishna that if one says: I will sin and Yom Kippur will atone for my sins, Yom Kippur does not atone for his sins. The Gemara comments: Let us say that the mishna is not in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, as it was taught in a baraita that Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi says: Yom Kippur atones for all transgressions of the Torah, whether one repented or did not repent. The Gemara answers: Even if you say that the mishna is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, it is different when it is on the basis of being permitted to sin. Even Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi agrees that Yom Kippur does not atone for the transgressions one commits only because he knows that Yom Kippur will atone for them.

עֲבֵירוֹת שֶׁבֵּין אָדָם לַמָּקוֹם וְכוּ׳. רָמֵי לֵיהּ רַב יוֹסֵף בַּר חָבוּ לְרַבִּי אֲבָהוּ: עֲבֵירוֹת שֶׁבֵּין אָדָם לַחֲבֵירוֹ אֵין יוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים מְכַפֵּר? וְהָא כְּתִיב: ״אִם יֶחֱטָא אִישׁ לְאִישׁ וּפִלְלוֹ אֱלֹהִים״! מַאן אֱלֹהִים — דַּיָּינָא.

§ It was taught in the mishna: Yom Kippur atones for sins committed against God but does not atone for sins committed against another person. Rav Yosef bar Ḥavu raised a contradiction before Rabbi Abbahu: The mishna states that Yom Kippur does not atone for sins committed against a fellow person, but isn’t it written: “If one man sin against another, God [Elohim] shall judge him [ufilelo]” (I Samuel 2:25). The word ufilelo, which may also refer to prayer, implies that if he prays, God will grant the sinner forgiveness. He answered him: Who is Elohim mentioned in the verse? It is referring to a judge [elohim] and not to God, and the word ufilelo in the verse indicates judgment. Atonement occurs only after justice has been done toward the injured party by means of a court ruling.

אִי הָכִי, אֵימָא סֵיפָא: ״וְאִם לַה׳ יֶחֱטָא אִישׁ מִי יִתְפַּלֶּל לוֹ״! הָכִי קָאָמַר: ״אִם יֶחֱטָא אִישׁ לְאִישׁ וּפִלְלוֹ אֱלֹהִים״ — יִמְחוֹל לוֹ. ״וְאִם לַה׳ יֶחֱטָא אִישׁ מִי יִתְפַּלֶּל בַּעֲדוֹ״ — תְּשׁוּבָה וּמַעֲשִׂים טוֹבִים.

Rav Yosef bar Ḥavu said to him: If so, say the following with regard to the latter clause of the verse: “But if a man sin against the Lord, who shall entreat [yitpallel] for him?” (I Samuel 2:25). This is difficult, since it has been established that the root pll is interpreted in this verse as indicating judgment, and therefore the latter clause of the verse implies that if one sins toward God there is no one to judge him. Rabbi Abbahu answered him: This is what the verse is saying: If one man sins against another, God [Elohim] shall forgive him [ufilelo]; if the sinner appeases the person against whom he has sinned, he will be forgiven. But if a man sin against the Lord, who shall entreat [yitpallel] for him? Repentance and good deeds. The root pll is to be interpreted as indicating forgiveness rather than judgment.

אָמַר רַבִּי יִצְחָק: כׇּל הַמַּקְנִיט אֶת חֲבֵירוֹ, אֲפִילּוּ בִּדְבָרִים — צָרִיךְ לְפַיְּיסוֹ, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״בְּנִי אִם עָרַבְתָּ לְרֵעֶךָ תָּקַעְתָּ לַזָּר כַּפֶּיךָ נוֹקַשְׁתָּ בְאִמְרֵי פִיךָ עֲשֵׂה זֹאת אֵפוֹא בְּנִי וְהִנָּצֵל כִּי בָאתָ בְכַף רֵעֶךָ לֵךְ הִתְרַפֵּס וּרְהַב רֵעֶיךָ״. אִם מָמוֹן יֵשׁ בְּיָדְךָ — הַתֵּר לוֹ פִּסַּת יָד, וְאִם לָאו — הַרְבֵּה עָלָיו רֵיעִים.

§ Rabbi Yitzḥak said: One who angers his friend, even only verbally, must appease him, as it is stated: “My son, if you have become a guarantor for your neighbor, if you have struck your hands for a stranger, you are snared by the words of your mouth… Do this now, my son, and deliver yourself, seeing you have come into the hand of your neighbor. Go, humble yourself [hitrapes] and urge [rehav] your neighbor” (Proverbs 6:1–3). This should be understood as follows: If you have money that you owe him, open the palm of [hater pisat] your hand to your neighbor and pay the money that you owe; and if not, if you have sinned against him verbally, increase [harbe] friends for him, i.e., send many people as your messengers to ask him for forgiveness.

(וְאָמַר) רַב חִסְדָּא: וְצָרִיךְ לְפַיְּיסוֹ בְּשָׁלֹשׁ שׁוּרוֹת שֶׁל שְׁלֹשָׁה בְּנֵי אָדָם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״יָשׁוֹר עַל אֲנָשִׁים וַיֹּאמֶר חָטָאתִי וְיָשָׁר הֶעֱוֵיתִי וְלֹא שָׁוָה לִי״.

Rav Ḥisda said: And one must appease the one he has insulted with three rows of three people, as it is stated: “He comes [yashor] before men, and says: I have sinned, and perverted that which was right, and it profited me not” (Job 33:27). Rav Ḥisda interprets the word yashor as related to the word shura, row. The verse mentions sin three times: I have sinned, and perverted, and it profited me not. This implies that one should make three rows before the person from whom he is asking forgiveness.

(וְאָמַר) רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר חֲנִינָא: כׇּל הַמְבַקֵּשׁ מָטוּ מֵחֲבֵירוֹ, אַל יְבַקֵּשׁ מִמֶּנּוּ יוֹתֵר מִשָּׁלֹשׁ פְּעָמִים, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״אָנָּא שָׂא נָא וְעַתָּה שָׂא נָא״. וְאִם מֵת — מֵבִיא עֲשָׂרָה בְּנֵי אָדָם וּמַעֲמִידָן עַל קִבְרוֹ, וְאוֹמֵר: חָטָאתִי לַה׳ אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וְלִפְלוֹנִי שֶׁחָבַלְתִּי בּוֹ.

Rabbi Yosei bar Ḥanina said: Anyone who asks forgiveness of his friend should not ask more than three times, as it is stated: “Please, please forgive the transgression of your brothers and their sin, for they did evil to you. And now, please forgive” (Genesis 50:17). The verse uses the word please three times, which shows that one need not ask more than three times, after which the insulted friend must be appeased and forgive. And if the insulted friend dies before he can be appeased, one brings ten people, and stands them at the grave of the insulted friend, and says in front of them: I have sinned against the Lord, the God of Israel, and against so-and-so whom I wounded.

רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה הֲוָה לֵיהּ מִילְּתָא לְרַבִּי אַבָּא בַּהֲדֵיהּ, אֲזַל אִיתִּיב אַדַּשָּׁא דְּרַבִּי אַבָּא בַּהֲדֵי דְּשָׁדְיָא אַמְּתֵיהּ מַיָּא, מְטָא זַרְזִיפֵי דְמַיָּא אַרֵישָׁא. אָמַר: עֲשָׂאוּנִי כְּאַשְׁפָּה. קְרָא אַנַּפְשֵׁיהּ: ״מֵאַשְׁפּוֹת יָרִים אֶבְיוֹן״. שְׁמַע רַבִּי אַבָּא וּנְפֵיק לְאַפֵּיהּ, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: הַשְׁתָּא צְרִיכְנָא לְמִיפַּק אַדַּעְתָּךְ, דִּכְתִיב: ״לֵךְ הִתְרַפֵּס וּרְהַב רֵעֶיךָ״.

The Gemara relates that Rabbi Yirmeya insulted Rabbi Abba, causing the latter to have a complaint against him. Rabbi Yirmeya went and sat at the threshold of Rabbi Abba’s house to beg him for forgiveness. When Rabbi Abba’s maid poured out the dirty water from the house, the stream of water landed on Rabbi Yirmeya’s head. He said about himself: They have made me into a trash heap, as they are pouring dirty water on me. He recited this verse about himself: “Who lifts up the needy out of the trash heap” (Psalms 113:7). Rabbi Abba heard what happened and went out to greet him. Rabbi Abba said to him: Now I must go out to appease you for this insult, as it is written: “Go, humble yourself [hitrapes] and urge your neighbor” (Proverbs 6:3).

רַבִּי זֵירָא כִּי הֲוָה לֵיהּ מִילְּתָא בַּהֲדֵי אִינִישׁ, הֲוָה חָלֵיף וְתָנֵי לְקַמֵּיהּ וּמַמְצֵי לֵיהּ, כִּי הֵיכִי דְּנֵיתֵי וְנִיפּוֹק לֵיהּ מִדַּעְתֵּיהּ.

It is related that when Rabbi Zeira had a complaint against a person who insulted him, he would pace back and forth before him and present himself, so that the person could come and appease him. Rabbi Zeira made himself available so that it would be easy for the other person to apologize to him.

רַב הֲוָה לֵיהּ מִילְּתָא בַּהֲדֵי הָהוּא טַבָּחָא, לָא אֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ. בְּמַעֲלֵי יוֹמָא דְכִפּוּרֵי אֲמַר אִיהוּ: אֵיזִיל אֲנָא לְפַיּוֹסֵי לֵיהּ. פְּגַע בֵּיהּ רַב הוּנָא, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: לְהֵיכָא קָא אָזֵיל מָר, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: לְפַיּוֹסֵי לִפְלָנְיָא. אָמַר: אָזֵיל אַבָּא לְמִיקְטַל נַפְשָׁא. אֲזַל וְקָם עִילָּוֵיהּ. הֲוָה יָתֵיב וְקָא פָלֵי רֵישָׁא, דַּלִּי עֵינֵיהּ וְחַזְיֵיהּ, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: אַבָּא אַתְּ? זִיל, לֵית לִי מִילְּתָא בַּהֲדָךְ. בַּהֲדֵי דְּקָא פָלֵי רֵישָׁא, אִישְׁתְּמִיט גַּרְמָא וּמַחְיֵיהּ בְּקוֹעֵיהּ וְקַטְלֵיהּ.

It is further related that Rav had a complaint against a certain butcher who insulted him. The butcher did not come before him to apologize. On Yom Kippur eve, Rav said: I will go and appease him. He met his student Rav Huna, who said to him: Where is my Master going? He said to him: I am going to appease so-and-so. Rav Huna called Rav by his name and said: Abba is going to kill a person, for surely that person’s end will not be good. Rav went and stood by him. He found the butcher sitting and splitting the head of an animal. The butcher raised his eyes and saw him. He said to him: Are you Abba? Go, I have nothing to say to you. While he was splitting the head, one of the bones of the head flew out and struck him in the throat and killed him, thereby fulfilling Rav Huna’s prediction.

רַב הֲוָה פָּסֵיק סִידְרָא קַמֵּיהּ דְּרַבִּי. עֲיַיל

The Gemara further relates: Rav was reciting the Torah portion before Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi.

אֲתָא רַבִּי חִיָּיא — הֲדַר לְרֵישָׁא. עֲיַיל בַּר קַפָּרָא — הֲדַר לְרֵישָׁא. אֲתָא רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בְּרַבִּי — הֲדַר לְרֵישָׁא. אֲתָא רַבִּי חֲנִינָא (בַּר) חָמָא, אָמַר: כּוּלֵּי הַאי נֶהְדַּר וְנֵיזִיל? לָא הֲדַר. אִיקְּפִיד רַבִּי חֲנִינָא, אֲזַל רַב לְגַבֵּיהּ תְּלֵיסַר מַעֲלֵי יוֹמֵי דְּכִפּוּרֵי וְלָא אִיפַּיַּיס.

Rabbi Ḥiyya, Rav’s uncle and teacher, came in, whereupon Rav returned to the beginning of the portion and began to read it again. Afterward, bar Kappara came in, and Rav returned to the beginning of the portion out of respect for bar Kappara. Then Rabbi Shimon, son of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, came in, and he returned again to the beginning of the portion. Then, Rabbi Ḥanina bar Ḥama came in, and Rav said to himself: Shall I go back and read so many times? He did not return but continued from where he was. Rabbi Ḥanina was offended because Rav showed that he was less important than the others. Rav went before Rabbi Ḥanina on Yom Kippur eve every year for thirteen years to appease him, but he would not be appeased.

וְהֵיכִי עָבֵיד הָכִי? וְהָאָמַר רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר חֲנִינָא: כׇּל הַמְבַקֵּשׁ מָטוּ מֵחֲבֵירוֹ אַל יְבַקֵּשׁ מִמֶּנּוּ יוֹתֵר מִשָּׁלֹשׁ פְּעָמִים! רַב שָׁאנֵי. וְרַבִּי חֲנִינָא, הֵיכִי עָבֵיד הָכִי? וְהָאָמַר רָבָא: כׇּל הַמַּעֲבִיר עַל מִדּוֹתָיו — מַעֲבִירִין לוֹ עַל כׇּל פְּשָׁעָיו!

The Gemara asks: How could Rav act this way? Didn’t Rabbi Yosei bar Ḥanina say: Anyone who requests forgiveness from another should not ask more than three times? The Gemara answers: Rav is different, since he was very pious and forced himself to act beyond the letter of the law. The Gemara asks: And how could Rabbi Ḥanina act this way and refuse to forgive Rav, though he asked many times? Didn’t Rava say: With regard to anyone who suppresses his honor and forgives someone for hurting him, God pardons all his sins?

אֶלָּא: רַבִּי חֲנִינָא חֶלְמָא חָזֵי לֵיהּ לְרַב דְּזַקְפוּהוּ בְּדִיקְלָא, וּגְמִירִי דְּכֹל דְּזַקְפוּהוּ בְּדִיקְלָא — רֵישָׁא הָוֵי. אָמַר: שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ בָּעֵי לְמֶעְבַּד רְשׁוּתָא וְלָא אִיפַּיַּיס, כִּי הֵיכִי דְּלֵיזִיל וְלִגְמַר אוֹרָיְיתָא בְּבָבֶל.

The Gemara explains: Rather, this is what happened: Rabbi Ḥanina saw in a dream that Rav was being hung on a palm tree, and he learned as a tradition that anyone about whom there is a dream in which he was being hung on a palm tree will become the head of a yeshiva. He said: Learn from this that providence has decreed that he must eventually become the head of the yeshiva. Therefore, I will not be appeased, so that he will have to go and study Torah in Babylonia. He was conscious of the principle that one kingdom cannot overlap with another, and he knew that once Rav was appointed leader, he, Rabbi Ḥanina, would have to abdicate his own position or die. Therefore, he delayed being appeased, so that Rav would go to Babylonia and be appointed there as head of the yeshiva. In this way, the dream would be fulfilled, as Rav would indeed be appointed as head of a yeshiva, but since he would be in Babylonia, Rabbi Ḥanina would not lose his own position.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: מִצְוַת וִידּוּי עֶרֶב יוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים עִם חֲשֵׁכָה. אֲבָל אָמְרוּ חֲכָמִים: יִתְוַדֶּה קוֹדֶם שֶׁיֹּאכַל וְיִשְׁתֶּה, שֶׁמָּא תִּטָּרֵף דַּעְתּוֹ בִּסְעוּדָה. וְאַף עַל פִּי שֶׁהִתְוַדָּה קוֹדֶם שֶׁאָכַל וְשָׁתָה — מִתְוַדֶּה לְאַחַר שֶׁיֹּאכַל וְיִשְׁתֶּה, שֶׁמָּא אֵירַע דְּבַר קַלְקָלָה בַּסְּעוּדָה. וְאַף עַל פִּי שֶׁהִתְוַדָּה עַרְבִית — יִתְוַדֶּה שַׁחֲרִית. שַׁחֲרִית — יִתְוַדֶּה בְּמוּסָף, בְּמוּסָף — יִתְוַדֶּה בְּמִנְחָה, בְּמִנְחָה — יִתְוַדֶּה בִּנְעִילָה.

§ The Sages taught: The main mitzva of confession is on Yom Kippur eve when darkness falls. But the Sages said: One should also confess on Yom Kippur eve before he eats and drinks at his last meal before the fast lest he become confused at the meal, due to the abundance of food and drink, and be unable to confess afterward. And although one confessed before he ate and drank, he confesses again after he eats and drinks, as perhaps he committed some sin during the meal itself. And although one confessed during the evening prayer on the night of Yom Kippur, he should confess again during the morning prayer. Likewise, although one confessed during the morning prayer, he should still confess during the additional prayer. Similarly, although one confessed during the additional prayer, he should also confess during the afternoon prayer; and although one confessed during the afternoon prayer, he should confess again during the closing prayer [ne’ila].

וְהֵיכָן אוֹמְרוֹ? יָחִיד אַחַר תְּפִלָּתוֹ, וּשְׁלִיחַ צִבּוּר אוֹמְרוֹ בָּאֶמְצַע. מַאי אָמַר? אָמַר רַב: ״אַתָּה יוֹדֵעַ רָזֵי עוֹלָם״. וּשְׁמוּאֵל אָמַר: ״מִמַּעֲמַקֵּי הַלֵּב״. וְלֵוִי אָמַר: ״וּבְתוֹרָתְךָ כָּתוּב לֵאמֹר״. רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר: ״רִבּוֹן הָעוֹלָמִים״.

And where in the Yom Kippur prayers does one say the confession? An individual says it after his Amida prayer, and the prayer leader says it in the middle of the Amida prayer. The Gemara asks: What does one say; what is the liturgy of the confession? Rav said: One says the prayer that begins: You know the mysteries of the universe, in accordance with the standard liturgy. And Shmuel said that the prayer begins with: From the depths of the heart. And Levi said that it begins: And in your Torah it is written, saying, and one then recites the forgiveness achieved by Yom Kippur as stated in the Torah. Rabbi Yoḥanan said that it begins: Master of the Universe.

רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אָמַר: ״כִּי עֲוֹנוֹתֵינוּ רַבּוּ מִלִּמְנוֹת וְחַטֹּאתֵינוּ עָצְמוּ מִסַּפֵּר״. רַב הַמְנוּנָא אָמַר: ״אֱלֹהַי, עַד שֶׁלֹּא נוֹצַרְתִּי אֵינִי כְּדַאי. עַכְשָׁיו שֶׁנּוֹצַרְתִּי, כְּאִילּוּ לֹא נוֹצַרְתִּי. עָפָר אֲנִי בְּחַיַּי, קַל וָחוֹמֶר בְּמִיתָתִי. הֲרֵי אֲנִי לְפָנֶיךָ כִּכְלִי מָלֵא בּוּשָׁה וּכְלִימָּה. יְהִי רָצוֹן מִלְּפָנֶיךָ שֶׁלֹּא אֶחֱטָא, וּמַה שֶׁחָטָאתִי — מְרוֹק בְּרַחֲמֶיךָ, אֲבָל לֹא עַל יְדֵי יִסּוּרִין״. וְהַיְינוּ וִידּוּיָא דְרָבָא כּוּלַּהּ שַׁתָּא, וּדְרַב הַמְנוּנָא זוּטָא בְּיוֹמָא דְכִפּוּרֵי.

Rabbi Yehuda said that one says: For our iniquities are too many to count and our sins are too great to number. Rav Hamnuna said: This is the liturgy of the confession: My God, before I was formed I was unworthy. Now that I have been formed, it is as if I had not been formed. I am dust while alive, how much more so when I am dead. See, I am before You like a vessel filled with shame and disgrace. May it be Your will that I may sin no more, and as for the sins I have committed before You, erase them in Your compassion, but not by suffering. The Gemara comments: This is the confession that Rava used all year long; and it was the confession that Rav Hamnuna Zuta used on Yom Kippur.

אָמַר מָר זוּטְרָא: לָא אֲמַרַן, אֶלָּא דְּלָא אָמַר: ״אֲבָל אֲנַחְנוּ חָטָאנוּ״, אֲבָל אָמַר: ״אֲבָל אֲנַחְנוּ חָטָאנוּ״ — תּוּ לָא צְרִיךְ. דְּאָמַר בַּר הַמְדּוּדֵי: הֲוָה קָאֵימְנָא קַמֵּיהּ דִּשְׁמוּאֵל, וַהֲוָה יָתֵיב, וְכִי מְטָא שְׁלִיחָא דְצִבּוּרָא וְאָמַר: ״אֲבָל אֲנַחְנוּ חָטָאנוּ״, קָם מֵיקָם, אֲמַר: שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ עִיקַּר וִידּוּי הַאי הוּא.

Mar Zutra said: We said only that one must follow all these versions when he did not say the words: But we have sinned. However, if he said the words: But we have sinned, he need not say anything further because that is the essential part of the confession. As bar Hamdudei said: I was standing before Shmuel and he was sitting; and when the prayer leader reached the words: But we have sinned, Shmuel stood. Bar Hamdudei said: Learn from here that this is the main part of the confession, and Shmuel stood up to emphasize the significance of these words.

תְּנַן הָתָם: בִּשְׁלֹשָׁה פְּרָקִים בַּשָּׁנָה כֹּהֲנִים נוֹשְׂאִין אֶת כַּפֵּיהֶן אַרְבָּעָה פְּעָמִים בַּיּוֹם: בְּשַׁחֲרִית, בְּמוּסָף, בְּמִנְחָה, וּבִנְעִילַת שְׁעָרִים. וְאֵלּוּ הֵן שְׁלֹשָׁה פְּרָקִים: בְּתַעֲנִיּוֹת, וּבְמַעֲמָדוֹת, וּבְיוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים.

§ We learned in a mishna there, in tractate Ta’anit: At three times in the year, priests raise their hands to recite the priestly benediction four times in a single day: In the morning prayer, in the additional prayer, in the afternoon prayer, and at the closing [ne’ila] of the gates. And these are the three times in the year: During communal fasts for lack of rain, on which the ne’ila prayer is recited; and during non-priestly watches [ma’amadot], when the Israelite members of the guard parallel to the priestly watch come and read the account of Creation (see Ta’anit 26a); and on Yom Kippur.

מַאי נְעִילַת שְׁעָרִים? רַב אָמַר: צְלוֹתָא יַתִּירְתָּא. וּשְׁמוּאֵל אָמַר: ״מָה אָנוּ מֶה חַיֵּינוּ״. מֵיתִיבִי: אוֹר יוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים מִתְפַּלֵּל שֶׁבַע וּמִתְוַדֶּה, בְּשַׁחֲרִית מִתְפַּלֵּל שֶׁבַע וּמִתְוַדֶּה, בְּמוּסָף מִתְפַּלֵּל שֶׁבַע וּמִתְוַדֶּה, בְּמִנְחָה מִתְפַּלֵּל שֶׁבַע וּמִתְוַדֶּה, בִּנְעִילָה מִתְפַּלֵּל שֶׁבַע וּמִתְוַדֶּה!

The Gemara asks: What is the closing of the gates, i.e., the ne’ila prayer? Rav said: It is an added prayer of Amida. And Shmuel said: It is not a full prayer but only a confession that begins with the words: What are we, what are our lives? The Gemara raises an objection to this from a baraita, as it was taught: On the night of Yom Kippur, one prays seven blessings in the Amida prayer and confesses; during the morning prayer, one prays seven blessings and confesses; during the additional prayer, one prays seven blessings and confesses; during the afternoon prayer, one prays seven blessings and confesses; and during the ne’ila prayer, one prays seven blessings and confesses. This concurs with Rav’s opinion that ne’ila is an added prayer.

תַּנָּאֵי הִיא, דְּתַנְיָא: יוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים עִם חֲשֵׁיכָה מִתְפַּלֵּל שֶׁבַע וּמִתְוַדֶּה, וְחוֹתֵם בְּוִידּוּי — דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי מֵאִיר. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: מִתְפַּלֵּל שֶׁבַע, וְאִם רָצָה לַחְתּוֹם בְּוִידּוּי — חוֹתֵם. תְּיוּבְתָּא דִשְׁמוּאֵל תְּיוּבְתָּא.

This is a dispute between tanna’im They all agree that ne’ila is an added prayer but disagree about the obligation to confess at the ne’ila prayer, as it was taught in a baraita: At the end of Yom Kippur, as darkness falls, one prays seven blessings of the Amida and confesses and ends with the confession; this is the statement of Rabbi Meir. And the Rabbis say: He prays seven blessings of the Amida, and if he wishes to end his prayer with a confession, he ends it in this way. The Gemara says: If so, this is a refutation of the opinion of Shmuel, since all agree that ne’ila is a complete prayer. The Gemara concludes: Indeed, it is a conclusive refutation.

עוּלָּא בַּר רַב נְחֵית קַמֵּיהּ דְּרָבָא. פְּתַח בְּ״אַתָּה בְּחַרְתָּנוּ״ וְסַיֵּים בְּ״מָה אָנוּ מֶה חַיֵּינוּ״, וְשַׁבְּחֵיהּ. רַב הוּנָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב נָתָן אָמַר: וְיָחִיד אוֹמְרָהּ אַחַר תְּפִלָּתוֹ.

The Gemara relates: Ulla bar Rav went down to lead the ne’ila prayer before Rava, who was in the synagogue. He opened the prayer with: You have chosen us, and he concluded with: What are we, what are our lives? And Rava praised him. Rav Huna, son of Rav Natan, said: And an individual says it after his Amida prayer. The individual says the confession after his Amida prayer, not within the Amida prayer as the prayer leader does.

אָמַר רַב: תְּפִלַּת נְעִילָה פּוֹטֶרֶת אֶת שֶׁל עַרְבִית. רַב לְטַעְמֵיהּ, דַּאֲמַר: צְלוֹתָא יַתִּירָה הִיא, וְכֵיוָן דְּצַלִּי לֵיהּ — תּוּ לָא צְרִיךְ.

Rav said: The ne’ila prayer exempts one from the evening prayer. Since one recited an added prayer after the afternoon prayer, when darkness fell, it serves as the evening prayer. The Gemara comments that Rav conforms to his line of reasoning above, as he said: It is an added prayer, and since he has prayed it he needs no further prayer in the evening.

וּמִי אָמַר רַב הָכִי? וְהָאָמַר רַב: הֲלָכָה כְּדִבְרֵי הָאוֹמֵר תְּפִלַּת עַרְבִית רְשׁוּת! לְדִבְרֵי הָאוֹמֵר חוֹבָה קָאָמַר.

The Gemara is surprised at this: And did Rav actually say this? Didn’t Rav say: The halakha is in accordance with the statement of the one who says that the evening prayer is optional? If it is optional, why would Rav use the term exempt? One is exempt even if he does not pray the closing prayer. The Gemara answers: He said this in accordance with the statement of the one who says that the evening prayer is mandatory. Even according to the opinion that maintains that the evening prayer is mandatory, if one recites ne’ila, he has fulfilled his obligation to recite the evening prayer.

מֵיתִיבִי: אוֹר יוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים מִתְפַּלֵּל שֶׁבַע וּמִתְוַדֶּה, שַׁחֲרִית שֶׁבַע וּמִתְוַדֶּה, מוּסָף שֶׁבַע וּמִתְוַדֶּה, בִּנְעִילָה מִתְפַּלֵּל שֶׁבַע וּמִתְוַדֶּה, עַרְבִית מִתְפַּלֵּל שֶׁבַע מֵעֵין שְׁמוֹנֶה עֶשְׂרֵה. רַבִּי חֲנִינָא בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל מִשּׁוּם אֲבוֹתָיו: מִתְפַּלֵּל שְׁמוֹנֶה עֶשְׂרֵה שְׁלֵימוֹת,

The Gemara raises an objection from that which we learned in a baraita: During the evening after Yom Kippur, one prays seven blessings in the Amida and confesses; during the morning prayer, one prays seven blessings in the Amida and confesses; during the additional prayer, one prays seven blessings in the Amida and confesses; during ne’ila one prays seven blessings in the Amida and confesses; and during the evening prayer, one prays seven blessings in an abridged version of the eighteen blessings of the weekday Amida prayer. One recites the first three blessings, the final three, and a middle blessing that includes an abbreviated form of the other weekday blessings. Rabbi Ḥanina ben Gamliel says in the name of his ancestors: One prays the full eighteen blessings of the weekday Amida prayer as usual,