Ready to get started?

Today’s Daf – Menachot 38 / Feb. 18th, 2026 / א׳ באדר תשפ״ו

Ready to get started?

🎉 Join the 2026/5786 #MegillahChallenge! 🎉

Rashi and Tosafot

When you open a page of Talmud, you will always find two main commentaries printed alongside the text. These are Rashi and Tosafot. Both are printed in Rashi script, a semi-cursive Hebrew typeface traditionally used for commentaries. Rashi’s commentary appears on the inner margin of the page, closer to the binding, while Tosafot is printed on the outer margin.

Rashi: The Essential Guide to the Text

Rashi—Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki—offers a concise and accessible explanation of the peshat (direct meaning) of the Gemara. His commentary is considered indispensable for learning Talmud. Without Rashi, the text is often difficult to follow. His notes explain difficult words, clarify logical progressions, and untangle complex discussions.

Rashi’s language is brief and to the point, designed to help the learner move smoothly through the sugya (Talmudic passage). His work is so integral to Talmud study that his commentary is rarely left out of any Talmudic discussion.

Rashi’s Talmud commentary was written by his students and disseminated in small booklets, leading to its nickname in Talmudic literature: HaKuntres (the booklet). This term often appears in Tosafot and other medieval commentaries.

Tosafot: Questions, Contradictions, and Comparisons

The Tosafot (literally “additions”) are a collection of commentaries written by a group of medieval Ashkenazi rabbis in the 12th and 13th centuries, many of whom were Rashi’s descendants or students.

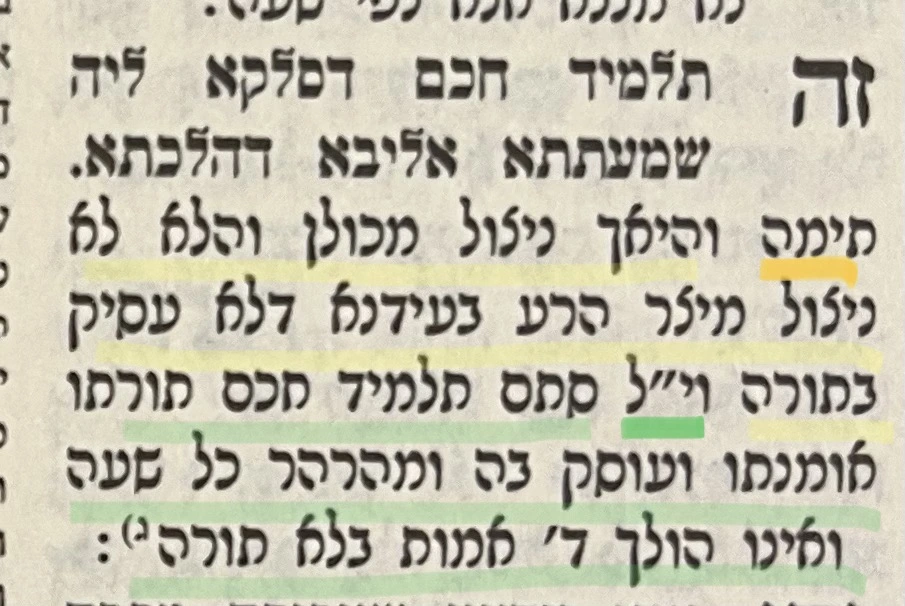

Unlike Rashi, Tosafot do not focus on explaining the straightforward meaning of the Gemara. Instead, they present questions, comparisons, and resolutions. They often raise contradictions between different sugyot across Shas (the entire Talmud) or challenge Rashi’s explanations. Their method involves deep analysis, exploring the Talmud as a unified whole and attempting to resolve inconsistencies between discussions in different tractates.

A typical passage of Tosafot will begin with a question (signaled by words like kashya, tama, or ve’im tomar—”if you will say”) and then offer a resolution (introduced with phrases like yesh lomar, veyesh letaretz, or amar Rabbi Yitzchak).

Tosafot is more complex and in-depth than Rashi, and it requires more advanced learning, but it is key to understanding the broader logic and methodology of the Talmud.

Who Was Rashi?

Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki (Rashi) lived in 11th-century France and Germany. He was a Torah scholar, halachic authority, and head of a yeshiva, but is best known for his commentaries on both the Torah and the Talmud.

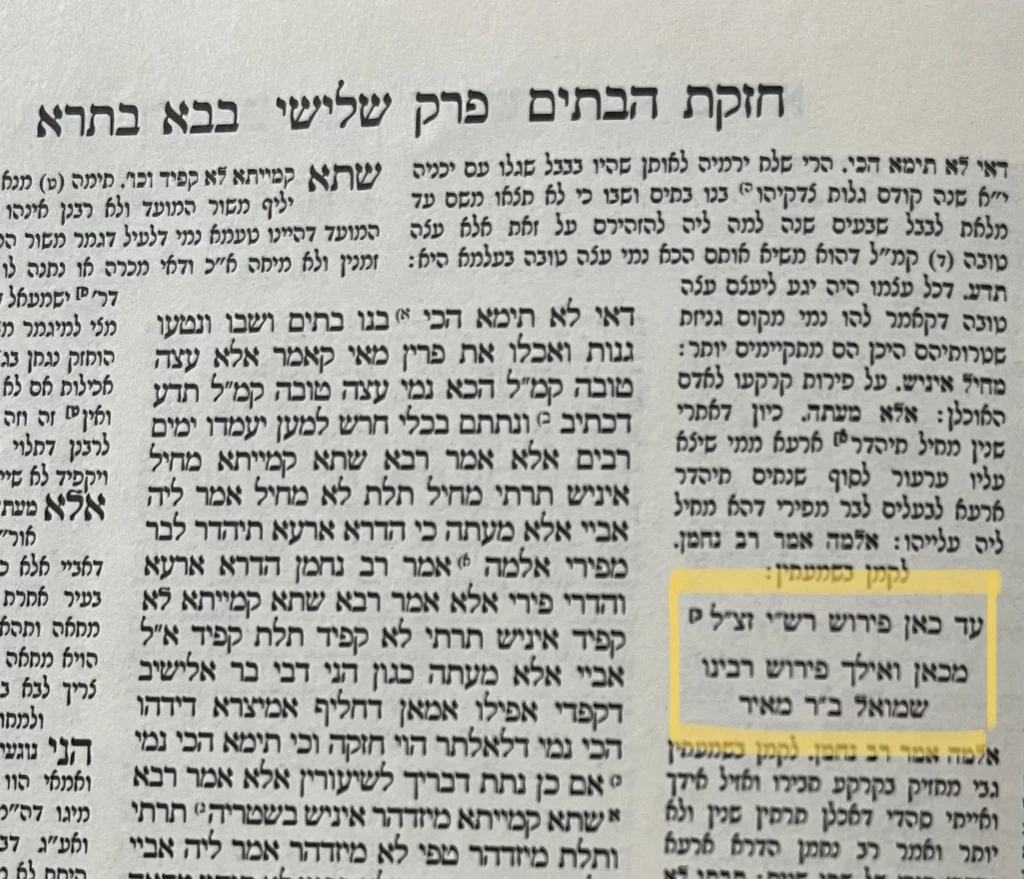

Rashi wrote commentary on nearly the entire Talmud. One notable exception is Tractate Bava Batra, which he did not complete. In the third chapter of that tractate, the commentary transitions to that of Rashbam, Rashi’s grandson. Other tractates such as Nedarim and Nazir likely do not contain Rashi’s commentary at all; although they appear under his name in standard editions, they were most likely written by other commentators. As such, some learners will refer to these commentaries as “meyuchas l’Rashi” (ascribed to Rashi) to reflect the pseudonymity.

In the image below: The yellow box surrounds the words indicating the place where Rashi’s commentary ends and the Rashbam’s picks up.

Who Were the Tosafot?

As aforementioned, the commentary of the “Tosafot” is compiled of different Ashkenazi medieval commentators known as the Ba’alei haTosafot (“authors of Tosafot”). Prominent figures include Rashbam, Rabbeinu Tam, and Rabbi Isaac of Dampierre (Ri)—many of whom were relatives or students of Rashi.

Although many different collections of Tosafot were compiled, the version we know today—the one printed on the side of each Talmud page—is a curated combination of several of these. Originally, Tosafot began as marginal notes on Rashi’s commentary but evolved into independent and complex analyses of the Talmudic text.

A famous (though unverified) story describes how the Tosafists divided up the entire Talmud, with each rabbi studying a different tractate in depth. After several years, they regrouped and discussed every contradiction or connection between sugyot they had found. Whether or not the story is historically accurate, it captures the Tosafist method: treating the Talmud as one cohesive work, and using cross-references to illuminate and resolve issues.

This post is part of Hadran’s educational series, helping you navigate and understand Talmudic concepts. Click here for more explorations into the world of Talmud.

For “The Complete Beginner’s Guide to Gemara” highly recommended course series, click here.