Ready to get started?

Today’s Daf – Menachot 38 / Feb. 18th, 2026 / א׳ באדר תשפ״ו

Ready to get started?

🎉 Join the 2026/5786 #MegillahChallenge! 🎉

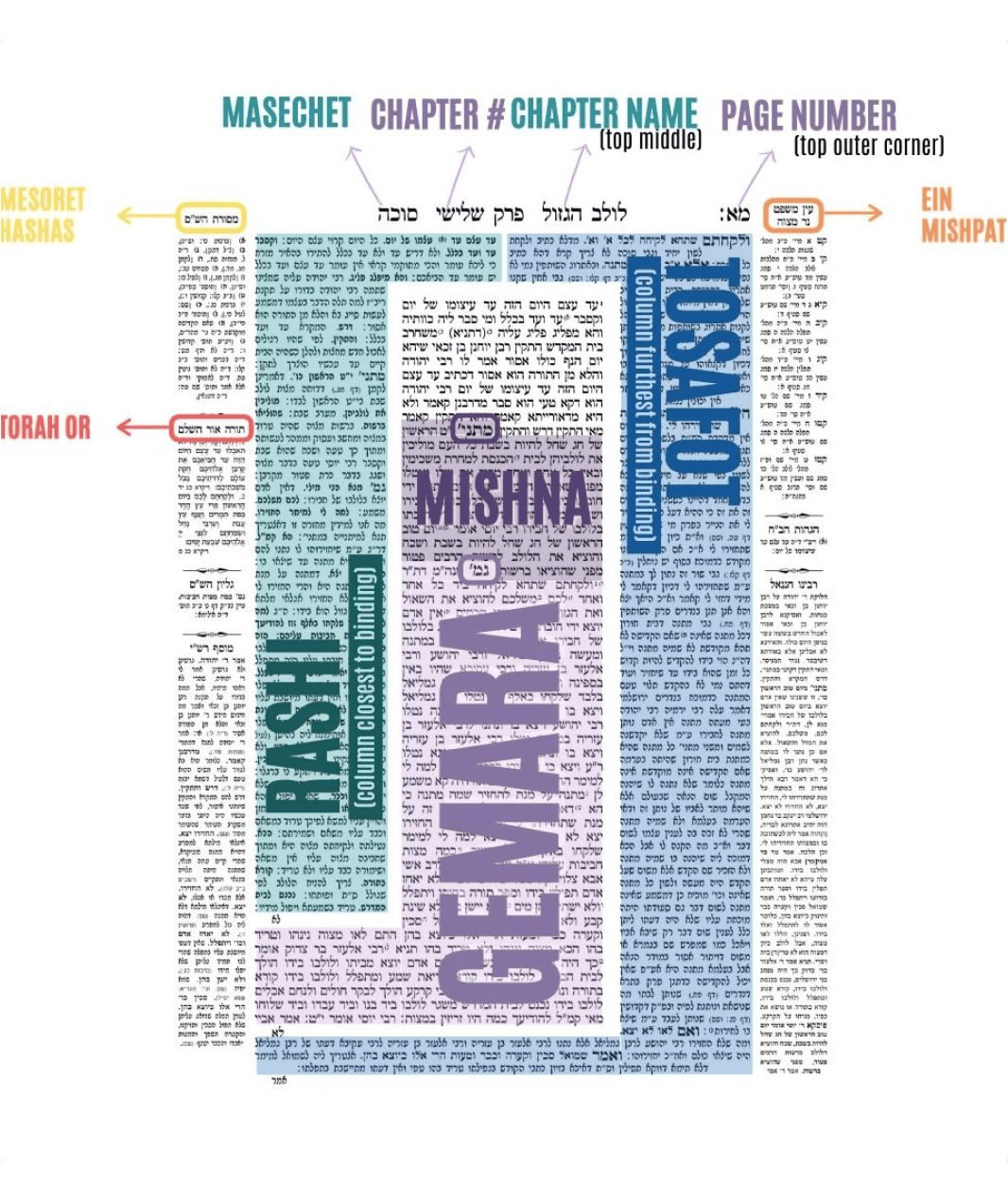

The Layout of a Talmud Page

At the top of every Talmud page, you’ll find essential information: the name of the tractate (masechet), the chapter number and title, the page number (daf), and whether it’s the front (amud alef) or back (amud bet) side of the page.

- On the right-hand side, you’ll see the chapter name (e.g., Lulav HaGazul), followed by the chapter number (Perek Shlishi – “Chapter Three”) and the name of the tractate (Sukkah).

- On the outer edge of the page, the daf number is printed (e.g., “41” – Mem Alef).

- Each daf has two sides: amud alef (a) and amud bet (b). A dot (.) after the page number indicates amud alef, while a colon (:) indicates amud bet. The image shown, for example, displays side bet of daf 41 (:מא).

Within the Gemara text itself:

- A colon (:) usually implies the end of sugya

- Other punctuation marks are often modern printing additions, were added by printers over the centuries and may vary between editions.

The classic printed page of the Talmud has a fixed structure, which has remained consistent for centuries.

At the center of the page, printed in the largest square script, you’ll find the Mishnah and Gemara texts:

- Before the Mishnah appears the abbreviation “מתני׳” (Matnitin), Aramaic for “our Mishnah.”

- Before the Gemara appears “גמ׳”, short for Gemara.

Surrounding the main text are the two most fundamental commentaries:

- On the inner margin, closer to the book’s binding, is Rashi’s commentary.

- On the outer margin, closer to the edge of the page, is the commentary of the Tosafot.

Above Rashi’s commentary is Masoret HaShas, a cross-referencing tool pointing to parallel sources in the Talmud.

Above Tosafot’s commentary is Ein Mishpat Ner Mitzvah, which provides references to halachic rulings based on the Talmudic discussion.

You may also find Torah Or, which gives references to biblical verses mentioned in the text. (In the sample image, Torah Or appears under Masoret HaShas, though its location may vary in different editions.)

The earliest Talmud printings date back to 15th-century Spain, but these were limited to individual tractates. The first complete printed edition of the entire Talmud (Shas) was published in Venice in the early 16th century, which also established the standard pagination system we still use today.

In the late 19th century, the Vilna Edition (Shas Vilna) was printed by the Widow and Brothers Romm publishing house, building on the Venetian layout. This edition became the most widespread and accepted format, and almost all Talmuds printed today follow this edition.

Over the centuries, censorship affected Talmud printings:

- Words like “goy“ (non-Jew) were often replaced with acronyms such as “Aku”m” (Oved Kochavim uMazzalot, “idol worshiper”) or “Kuti“ (Samaritan).

- The term “min“ (heretic) was sometimes replaced with “Apikores“ or “Tzeduki“ (Sadducee).

For a long time, nearly all Talmuds used only the Vilna format. That changed in 1967 with the publication of the first volume of the Steinsaltz Talmud, which did not preserve the traditional layout. Steinsaltz introduced innovations like paragraph divisions, punctuation, vocalization (nikkud), translations, and explanations—revolutionizing accessibility and study.

Why Does Every Tractate Start on Page 2?

Talmud tractates always begin on daf bet (page 2), not daf alef (page 1). This practice originates from early printing customs: the title page of each tractate was counted as page 1. Therefore, the first page of actual Talmudic text became page 2.

Over time, symbolic explanations emerged:

- Some say page 1 represents reverence for God (Yirat Hashem), reminding us that awe and humility must precede learning.

- Others interpret it as a reminder that there is always more Torah to learn—page 1 is what we have yet to study.

The Decorative Frame at the Start of a Tractate

The first word of every tractate is highlighted with a decorative border. In most tractates, this ornamentation is made up of aesthetic designs like flowers. But there are a few exceptions—namely, Sotah, Bava Kama, Bava Batra, and Avodah Zarah. In these cases, the decoration includes serpents.

Why snakes? Some suggest it’s symbolic: these tractates deal with sin, damage, and idolatry, and the snake represents the original sin and the introduction of harm into the world.

This post is part of Hadran’s educational series, helping you navigate and understand Talmudic concepts. Click here for more explorations into the world of Talmud.

For “The Complete Beginner’s Guide to Gemara” highly recommended course series, click here.