Bava Batra 104

פָּחוֹת כׇּל שֶׁהוּא – יְנַכֶּה, יָתֵר כׇּל שֶׁהוּא – יַחֲזִיר. הָא סְתָמָא – כְּ״הֵן חָסֵר הֵן יָתֵר״ דָּמֵי!

and he gave him even the slightest amount less that what was stipulated, the seller must deduct the difference from the purchase price of the field and return money to the buyer. If he gave him even the slightest amount more than what was stipulated, the buyer must return the difference to the seller. The reason that even the slightest difference in value must be returned is that the seller specified that he was selling land measured precisely with a rope. But had he sold the land without further specification, it would be like he sold it saying that it is a beit kor more or less.

אֵימָא סֵיפָא – וְאִם אָמַר לוֹ: ״הֵן חָסֵר הֵן יָתֵר״; אֲפִילּוּ פִּיחֵת רוֹבַע לִסְאָה אוֹ הוֹתִיר רוֹבַע לִסְאָה – הִגִּיעוֹ. הָא סְתָמָא – כְּמִדָּה בְּחֶבֶל דָּמֵי! אֶלָּא מֵהָא לֵיכָּא לְמִשְׁמַע מִינַּהּ.

The Gemara rejects this argument by proposing another, completely opposite proof: Say the latter clause of the mishna: And if the seller said to the buyer that he is selling him a beit kor of land more or less, then even if he gave him one-quarter of a kav per se’a less than what was stipulated, or he gave him one-quarter of a kav per se’a more than what was stipulated, it is his and the sale is valid. One can infer: The reason that the sale is valid is that he specified that he was selling a beit kor of land more or less. But had he sold the land without further specification, it would be like he sold it saying that he was selling the land measured precisely with a rope. Rather, since the mishna can be interpreted in two opposite ways, no inference is to be learned from the mishna.

תָּא שְׁמַע: ״בֵּית כּוֹר עָפָר אֲנִי מוֹכֵר לָךְ״; ״כְּבֵית כּוֹר עָפָר אֲנִי מוֹכֵר לָךְ״; ״הֵן חָסֵר הֵן יָתֵר אֲנִי מוֹכֵר לָךְ״ – אֲפִילּוּ פִּיחֵת רוֹבַע לִסְאָה, אוֹ הוֹתִיר רוֹבַע לִסְאָה – הִגִּיעוֹ. אַלְמָא סְתָמָא נָמֵי, כְּ״הֵן חָסֵר הֵן יָתֵר״ דָּמֵי! הָתָם, פָּרוֹשֵׁי קָא מְפָרֵשׁ – אֵיזֶהוּ בֵּית כּוֹר שֶׁהִיא כְּבֵית כּוֹר? כְּגוֹן דַּאֲמַר לֵיהּ: ״הֵן חָסֵר הֵן יָתֵר״.

The Gemara tries to present another proof: Come and hear a proof from a baraita: If the seller said to the buyer: I am selling you a plot of earth the size of a beit kor; or he said to him: I am selling you a plot of earth about the size of a beit kor; or he said to him: I am selling you a beit kor more or less; then even if he gave him one-quarter of a kav per se’a less than what was stipulated, or he gave him one-quarter of a kav per se’a more than what was stipulated, it is his and the sale is valid. One can infer: Apparently, selling a beit kor of land without further specification is also like selling it more or less. The Gemara rejects this proof: There, the tanna is explaining his statement, which should be understood as follows: When is the phrase a beit kor treated like the phrase about the size of a beit kor? In a case where the seller says to the buyer: I am selling you a beit kor more or less.

מַתְקֵיף לַהּ רַב אָשֵׁי: אִם כֵּן, ״אֲנִי מוֹכֵר לָךְ״ ״אֲנִי מוֹכֵר לָךְ״ לְמָה לִי? אֶלָּא לָאו שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ סְתָמָא נָמֵי כְּ״הֵן חָסֵר הֵן יָתֵר״ דָּמֵי? שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ.

Rav Ashi objects to this: If that is so, then why do I need to repeat the words: I am selling you, three times? The fact that the baraita repeats these words in each clause indicates that it is discussing three separate sale transactions, and not that the three clauses are all referring to one case. Rather, isn’t it correct to conclude from the baraita that selling a beit kor of land without further specification is like selling it more or less? The Gemara affirms: Conclude from the baraita that this is so.

מַהוּ מַחֲזִיר לוֹ? מָעוֹת וְכוּ׳. לְיַפּוֹת כֹּחוֹ שֶׁל מוֹכֵר אָמְרִינַן, לְיַפּוֹת כֹּחוֹ שֶׁל לוֹקֵחַ לָא אָמְרִינַן?!

§ With regard to a buyer who received too much land and now must compensate the seller, the mishna teaches: What does he return to him? He pays him money, and if the seller so wishes, the buyer returns the surplus land to him, because the Sages said that the buyer pays money in order to enhance the power of the seller. In other words, the Sages allowed the seller to choose whether to take back the surplus land or to demand payment for it from the buyer, even though this effectively forces the buyer to purchase the surplus land from him. The Gemara asks: Is it correct that we say that the seller’s power should be enhanced, and that we do not say that the buyer’s power should be enhanced?

וְהָתַנְיָא: פִּיחֵת שִׁבְעַת קַבִּין וּמֶחֱצָה לְכוֹר, אוֹ הוֹתִיר שִׁבְעַת קַבִּין וּמֶחֱצָה לְכוֹר – הִגִּיעוֹ. יוֹתֵר מִכָּאן – כּוֹפִין אֶת הַמּוֹכֵר לִמְכּוֹר וְאֶת הַלּוֹקֵחַ לִיקַּח.

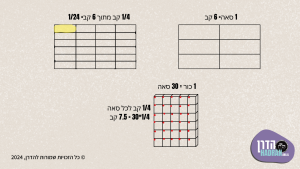

But isn’t it taught otherwise in a baraita: If the seller gave the buyer seven and a half kav per kor less than what was stipulated, which is the equivalent of a quarter-kav per se’a, as a kor is equal to thirty se’a, or he gave him seven and a half kav per kor more than what was stipulated, it is his and the sale is valid. If the difference is greater than that amount, the court compels the seller to sell and the buyer to buy the difference. This indicates that we also say that the buyer’s power should be enhanced, since if the buyer so wishes, the seller is compelled to sell him land and accept payment for it.

הָתָם, כְּגוֹן דַּהֲוָה יַקִּירָא מֵעִיקָּרָא, וְזָל הַשְׁתָּא; דְּאָמְרִינַן לֵיהּ: אִי אַרְעָא יָהֲבַתְּ לִי – הַב לִי כְּזוּלָא דְּהַשְׁתָּא.

The Gemara replies: There, the baraita is not discussing a case where the buyer wishes to acquire the surplus land, but rather with a case where the land was initially, at the time of the sale, expensive, but now it is cheap, and the seller wants the buyer to pay him for the surplus land according to the initial higher rate. In this case, we say to the seller, in the name of the buyer: If you wish to give me land and receive money, give me the land according to the current, cheaper rate. This is what the baraita is referring to when it states that the seller is compelled to sell.

וְהָתַנְיָא: כְּשֶׁהוּא נוֹתֵן לוֹ – נוֹתֵן לוֹ כְּשַׁעַר שֶׁלָּקַח מִמֶּנּוּ! הָתָם, כְּגוֹן דַּהֲוָה זוּלָא מֵעִיקָּרָא, וְיָקְרָא לַהּ הַשְׁתָּא.

The Gemara raises a difficulty: But isn’t it taught in a baraita: When he gives him money in payment for the surplus land, he gives it to him according to the rate at which he had bought the rest of the land from him? The Gemara replies: There the baraita is referring to a case where the land was initially cheap but now it is expensive. If, in such a case, the seller wants the buyer to pay him for the surplus land, he is compelled to sell it to him according to the cheap rate from the time of the original sale.

שֶׁאִם שִׁיֵּיר בַּשָּׂדֶה בֵּית תִּשְׁעָה קַבִּין וְכוּ׳. אָמַר רַב הוּנָא: תִּשְׁעָה קַבִּין שֶׁאָמְרוּ, וַאֲפִילּוּ בְּבִקְעָה גְּדוֹלָה.

§ The mishna teaches: As, if the surplus in the field was an area required for the sowing of nine kav of seed, and in a garden an area required for the sowing of a half-kav of seed, or, according to the Rabbi Akiva, an area required for the sowing of a quarter-kav of seed, the buyer can return the surplus land to the seller, and the seller cannot demand payment in money. Rav Huna says: The halakha that was stated in the mishna, that a surplus in the size of an area required for the sowing of nine kav of seed can be returned to the seller, applies even in a large valley which measures several kor. If the surplus is a significant plot of land equal in size to an area required for the sowing of nine kav of seed, the buyer can return it to the seller, even if it is less than one-quarter of a kav per se’a, i.e., less than one twenty-fourth the size of the field that was sold.

וְרַב נַחְמָן אָמַר: נוֹתֵן שִׁבְעַת קַבִּין וּמֶחֱצָה לְכׇל כּוֹר וָכוֹר.

And Rav Naḥman says: He calculates seven and a half kav for each and every kor, which is equivalent to one-quarter of a kav per se’a. As long as the surplus does not exceed that ratio, he is not required to return it, even if the surplus is greater than the area required for the sowing of nine kav.

וְאִי אִיכָּא מִילְּתָא יַתִּירָא, דְּהָוֵי לְתִשְׁעַת קַבִּין – הָדְרִי.

And if after this calculation there is still a surplus in excess of a quarter-kav per se’a, equal in size to an area required for the sowing of nine kav of seed, the entire surplus must be returned.

אֵיתִיבֵיהּ רָבָא לְרַב נַחְמָן: ״שֶׁאִם שִׁיֵּיר בַּשָּׂדֶה בֵּית תִּשְׁעַת קַבִּין״ – לָאו דְּזַבֵּין לֵיהּ כּוֹרַיִים? לָא, דְּזַבֵּין לֵיהּ כּוֹר.

Rava raised an objection to Rav Naḥman: The mishna teaches that if the surplus in the field was an area required for the sowing of nine kav of seed, the buyer returns the land to the seller. Isn’t this the halakha even in a case where he sold him a field measuring two kor? This would seem to indicate that even if the surplus does not exceed a quarter-kav per se’a, as a quarter-kav per se’a in a field of two kor is fifteen kav, the sole determining factor is whether or not the surplus is equal in size to an area required for the sowing of nine kav. Rav Naḥman rejects this argument: No, the case in the mishna is specifically where he sold him a field measuring one kor.

״וּבַגִּנָּה בֵּית חֲצִי קַב״ – לָאו דְּזַבֵּין לֵיהּ סָאתַיִם? לָא, דְּזַבֵּין לֵיהּ סְאָה.

Rava raised a further objection to Rav Naḥman: We learned in the continuation of the mishna that if the surplus in a garden was an area required for the sowing of a half-kav of seed, the buyer returns the land to the seller. Isn’t this the halakha even in a case where he sold him a garden measuring two se’a? Once again, this would seem to indicate that the surplus is returned to the seller, provided that it is equal in size to the minimum measure of a garden, even if the surplus does not exceed one-half of a kav per two se’a, which is equivalent to one-quarter of a kav per se’a. Rav Naḥman rejects this argument as well: No, the case in the mishna is where he sold him a garden measuring a se’a, so that the surplus is proportionately twice as large.

״וּכְדִבְרֵי רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא, בֵּית רוֹבַע״ – מַאי, לָאו דְּזַבֵּין לֵיהּ סְאָה? לָא, דְּזַבֵּין לֵיהּ חֲצִי סְאָה.

Rava raised yet another objection to Rav Naḥman from the next clause in the mishna, which states: Or, according to the statement of Rabbi Akiva, if the surplus in the garden was an area required for sowing a quarter-kav of seed, the buyer returns the land to the seller. What, isn’t this the halakha even in a case where he sold him a garden measuring a se’a? In that case, the surplus does not exceed one-quarter of a kav per se’a, and nevertheless the surplus is returned to the seller, provided that it is equal in size to the minimum measure of a garden. Rav Naḥman also rejects this argument: No, the case in the mishna is where he sold him a garden measuring a half-se’a, so that the surplus is proportionately twice as large.

בָּעֵי רַב אָשֵׁי: שָׂדֶה – וְנַעֲשֵׂית גִּנָּה; גִּנָּה – וְנַעֲשֵׂיתָ שָׂדֶה, מַאי? תֵּיקוּ.

The mishna teaches that in the case of a field, the buyer can return the land itself if the surplus was an area required for the sowing of nine kav of seed, and in the case of a garden, if the surplus was an area required for the sowing of a half-kav of seed. Rav Ashi raises a dilemma: If one sold a field and it turned out that the plot was larger than had been stipulated, but before the buyer returned the surplus, the plot was turned into a garden, or if it was initially a garden and it was turned into a field (see 11a), what is the halakha? Is the surplus governed by the halakhot applying to a field or by those applying to a garden? The Gemara answers: The dilemma shall stand unresolved, as no answer has been found.

תָּנָא: אִם הָיָה סָמוּךְ לְשָׂדֵהוּ – אֲפִילּוּ כָּל שֶׁהוּא, מַחֲזִיר לוֹ קַרְקַע.

A Sage taught in a baraita: If the field being sold was adjacent to another field belonging to the seller, then even if the surplus was of a minimal amount, the buyer can return the land itself to the seller, and the seller cannot demand payment in money. This is because the seller loses nothing when he receives a small tract of land, as he can cultivate it along with his adjoining field.

בָּעֵי רַב אָשֵׁי: בּוֹר, מַהוּ שֶׁתַּפְסִיק? אַמַּת הַמַּיִם, מַהוּ שֶׁתַּפְסִיק? דֶּרֶךְ הָרַבִּים, מַהוּ שֶׁתַּפְסִיק? רִיכְבָּא דְּדִיקְלָא, מַהוּ שֶׁתַּפְסִיק? תֵּיקוּ.

Rav Ashi raises a set of dilemmas: With regard to a pit between the surplus in the sold field and the adjoining field belonging to the seller, what is the halakha: Should the pit be considered an interposition between the two fields? With regard to a water channel between the two fields, what is the halakha: Should the water channel be considered an interposition? With regard to the public thoroughfare, what is the halakha: Should the public thoroughfare be considered an interposition? With regard to a row of palm trees, what is the halakha: Should a row of palm trees be considered an interposition? The Gemara states: All these dilemmas shall stand unresolved.

וְלֹא אֶת הָרוֹבַע בִּלְבַד מַחֲזִיר לוֹ, אֶלָּא כָּל הַמּוֹתָר. כְּלַפֵּי לְיָיא? תָּאנֵי רָבִין בַּר רַב נַחְמָן: לֹא אֶת הַמּוֹתָר בִּלְבַד מַחֲזִיר לוֹ, אֶלָּא אֶת כָּל הָרְבָעִין כּוּלָּן.

§ The mishna teaches that if the surplus is greater than a quarter-kav per se’a, it is not only the quarter-kav that the buyer returns; rather, he returns all of the surplus. Since he is already required to make a refund, the refund must be made in the precise amount. The Gemara raises a question: Isn’t it the opposite [kelappei layya]? The buyer is required to return the surplus even when the quarters of a kav remain in his possession. Ravin bar Rav Naḥman taught the mishna as follows: Not only must the buyer return the extra land that is beyond the limit of a quarter-kav area per beit se’a, but he must also return to him every one of the extra quarter-kav areas of land that he received beyond the stated area of a beit kor. When he is required to return the surplus, he returns not only the surplus, but also all the quarter-kav areas over and above what had originally been stipulated to be included in the sale.

מַתְנִי׳ ״מִדָּה בְּחֶבֶל אֲנִי מוֹכֵר לָךְ, הֵן חָסֵר הֵן יָתֵר״ – בִּטֵּל ״הֵן חָסֵר הֵן יָתֵר״ ״מִדָּה בְּחֶבֶל״. ״הֵן חָסֵר הֵן יָתֵר, מִדָּה בְּחֶבֶל״ –

MISHNA: If the seller says to the buyer: I am selling you a plot of land of a certain size measured precisely with a rope more or less, thereby attaching to the sale two contradictory stipulations; in this case, the words: More or less, nullify the words: Measured precisely with a rope. Accordingly, if the surplus did not exceed a quarter-kav per se’a, the sale is valid as is. Similarly, if the seller says to the buyer: I am selling you a plot of land of a certain size more or less measured precisely with a rope,