Abaye disagrees with those who said that the larger courtyard absorbs the inhabitants of the smaller courtyard as how can there be a barrier that connects rather than separates and therefore forbids (like planting near a vineyard? Various rabbis try to show Abaye that walls can connect/forbid in various situations but each time Abaye responds that the case isn’t comparable. Rav Yehuda brings a case of encampments in large spaces shared like the courtyards discussed (walls seen from one side but not the other) – they are viewed as one whole unit if the outer ones can see walls when going into the inner one for the same logic as stated before that the larger courtyard absorbs the inhabitants of the smaller. Rav Chisda and Rav Mesharshia disagree about whether an embankment of 5 handbreadths can join with a wall of 5 and be considered a proper wall for laws of courtyards. A bratia is brought against Rav Chisda and three answers are brought. If the situation changes on Shabbat and a wall between courtyards is breached, does this prevent the inhabitants from carrying as they are now viewed as one whole, or can they rely on the fact that when Shabbat started, they were permitted and therefore also now. Can we learn the answer from our mishna?

Eruvin 93

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Today’s daily daf tools:

Today’s daily daf tools:

Delve Deeper

Broaden your understanding of the topics on this daf with classes and podcasts from top women Talmud scholars.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Eruvin 93

סִיכֵּךְ עַל גַּבֵּי אַכְסַדְרָה שֶׁיֵּשׁ לָהּ פַּצִּימִין — כְּשֵׁירָה. וְאִילּוּ הִשְׁוָה פַּצִּימֶיהָ — פְּסוּלָה.

If one placed roofing on top of a portico that has doorposts, i.e., a portico with two parallel walls that are valid for a sukka, as well as posts in the corners supporting the portico and protruding like doorposts, which are considered as sealing the other two sides of the portico, it is a valid sukka. However, if he evened the doorposts by constructing walls adjacent to the existing walls, obscuring the posts so that they do not protrude, the sukka is invalid. This teaching indicates that the creation of a partition can cause prohibition.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי: לְדִידִי כְּשֵׁירָה, לְדִידָךְ סִילּוּק מְחִיצּוֹת הִיא.

Abaye said to him: In my opinion, with regard to that case of a portico, the sukka is valid. However, even according to your opinion, this is another instance of the removal of partitions. Evening the doorposts does not render the sukka invalid through the establishment of new partitions, but because it negates the original partitions of the sukka.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַבָּה בַּר רַב חָנָן לְאַבָּיֵי: וְלֹא מָצִינוּ מְחִיצָה לְאִיסּוּר? וְהָתַנְיָא: בַּיִת שֶׁחֶצְיוֹ מְקוֹרֶה וְחֶצְיוֹ אֵינוֹ מְקוֹרֶה, גְּפָנִים כָּאן — מוּתָּר לִזְרוֹעַ כָּאן.

Rabba bar Rav Ḥanan said to Abaye: And didn’t we find that a partition causes prohibition? But wasn’t it taught in a baraita: With regard to a house, half of which is roofed and half unroofed, if there are vines here, under the roofed section of the house, it is permitted to sow crops there, in the open section. The reason is that it is as though the edge of the roof descends to the ground and forms a partition between the two sections of the house.

וְאִילּוּ הִשְׁוָה אֶת קֵרוּיוֹ — אָסוּר. אֲמַר לֵיהּ: הָתָם סִילּוּק מְחִיצּוֹת הוּא.

And if he evened its roofing, by extending the roof to cover the entire house, it would be prohibited to sow other crops there. It is evident that the very placement of a partition, in this case a roof, causes prohibition. Abaye said to him: There too it is an instance of the removal of partitions. It is prohibited to sow not due to the added roofing; rather, it is prohibited due to the negation of the imaginary partition.

שְׁלַח לֵיהּ רָבָא לְאַבָּיֵי בְּיַד רַב שְׁמַעְיָה בַּר זְעֵירָא: וְלֹא מָצִינוּ מְחִיצָה לְאִיסּוּר? וְהָתַנְיָא: יֵשׁ בִּמְחִיצוֹת הַכֶּרֶם לְהָקֵל וּלְהַחֲמִיר, כֵּיצַד? כֶּרֶם הַנָּטוּעַ עַד עִיקַּר מְחִיצָה — זוֹרֵעַ מֵעִיקַּר מְחִיצָה וְאֵילָךְ. שֶׁאִילּוּ אֵין שָׁם מְחִיצָה מַרְחִיק אַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת וְזוֹרֵעַ, וְזֶה הוּא מְחִיצּוֹת הַכֶּרֶם לְהָקֵל.

Rava sent a different proof to Abaye by means of Rav Shemaya bar Ze’eira, with regard to the same issue. And didn’t we find a partition causes prohibition? But wasn’t it taught in a baraita: There is an element in the partitions of a vineyard that causes leniency with regard to diverse kinds of seeds and an element that causes stringency. How so? With regard to a vineyard that is planted until the very base of a partition, one sows crops from the base of the other side of the partition onward. This is a leniency, as were there no partition there, he would be required to distance himself four cubits from the last vine and only then sow there. And this is an element in partitions of a vineyard that causes leniency.

וּלְהַחֲמִיר כֵּיצַד? הָיָה מָשׁוּךְ מִן הַכּוֹתֶל אַחַת עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה — לֹא יָבִיא זֶרַע לְשָׁם, שֶׁאִילְמָלֵי אֵין מְחִיצָה מַרְחִיק אַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת וְזוֹרֵעַ, וְזוֹהִי מְחִיצוֹת הַכֶּרֶם לְהַחְמִיר.

And as for an element in partitions that causes stringency, how so? If the vineyard was distanced eleven cubits from a wall, one may not bring the seeds of other crops there, between the vineyard and the wall, and sow that area. This is a stringency, as were there no partition, it would suffice to distance himself four cubits from the last vine, and sow there. This is an element of partitions in a vineyard that causes stringency, a clear situation of a partition that causes prohibition.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ: וְלִיטַעְמָיךְ, אוֹתְבַן מִמַּתְנִיתִין, דִּתְנַן: קָרַחַת הַכֶּרֶם, בֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים: עֶשְׂרִים וְאַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת, וּבֵית הִלֵּל אוֹמְרִים: שֵׁשׁ עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה. מְחוֹל הַכֶּרֶם, בֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים: שֵׁשׁ עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה, וּבֵית הִלֵּל אוֹמְרִים: שְׁתֵּים עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה.

Abaye said to him: And according to your reasoning that this presents a difficulty, raise an objection against our opinion from a mishna, rather than a less authoritative baraita, as we learned in a mishna: With regard to a clearing in a vineyard, Beit Shammai say: Its measure is twenty-four cubits, and Beit Hillel say: Sixteen cubits. With regard to the perimeter of a vineyard, Beit Shammai say: Sixteen cubits, and Beit Hillel say: Twelve cubits.

וְאֵיזוֹ הִיא קָרַחַת הַכֶּרֶם? כֶּרֶם שֶׁחָרַב אֶמְצָעִיתוֹ. אִם אֵין שָׁם שֵׁשׁ עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה — לֹא יָבִיא זֶרַע לְשָׁם, הָיוּ שָׁם שֵׁשׁ עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה — נוֹתֵן לוֹ כְּדֵי עֲבוֹדָתוֹ, וְזוֹרֵעַ אֶת הַמּוֹתָר.

The mishna explains: And what is a clearing in a vineyard? It is referring to a vineyard whose middle section was laid bare of vines. If there are not sixteen cubits across in the clearing, one may not bring foreign seeds and sow them there, due to the Torah prohibition against sowing other crops in a vineyard (Deuteronomy 22:9). If there were sixteen cubits across in the clearing, one provides the vineyard with its requisite work area, i.e., four cubits along either side of the vines are left unsown to facilitate cultivation of the vines, and he sows the rest of the cleared area with foreign crops.

אֵי זוֹ הִיא מְחוֹל הַכֶּרֶם? בֵּין הַכֶּרֶם לַגָּדֵר. שֶׁאִם אֵין שָׁם שְׁתֵּים עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה — לֹא יָבִיא זֶרַע לְשָׁם, הָיוּ שָׁם שְׁתֵּים עֶשְׂרֵה אַמָּה — נוֹתֵן לוֹ כְּדֵי עֲבוֹדָתוֹ, וְזוֹרֵעַ אֶת הַמּוֹתָר.

The mishna continues: What is the perimeter of a vineyard? It is the vacant area between the vineyard and the fence surrounding it. If there are not twelve cubits in that area, one may not bring foreign seeds and sow them there. If there are twelve cubits in that area, he provides the vineyard with its requisite work area, four cubits, and he sows the rest. However, were the vineyard not surrounded by a fence, all he would need to do is distance himself four cubits from the last vine. It is clear from this halakha that the partition causes prohibition.

אֶלָּא — הָתָם לָאו הַיְינוּ טַעְמָא, דְּכֹל אַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת לְגַבֵּי כֶרֶם עֲבוֹדַת הַכֶּרֶם. לְגַבֵּי גָדֵר, כֵּיוָן דְּלָא מִזְדַּרְעָן — אַפְקוֹרֵי מַפְקַר לְהוּ. דְּבֵינֵי בֵּינֵי, אִי אִיכָּא אַרְבַּע — חֲשִׁיבָן, וְאִי לָא — לָא חֲשִׁיבָן.

Rather, the objection was not raised from there because there, isn’t this the reason that the partition is not considered to cause prohibition? It is because the entire area of four cubits alongside a vineyard is considered the vineyard’s work area, and is therefore an actual part of it. Likewise, with regard to the four cubits alongside the fence surrounding the vineyard, since they cannot easily be sown due to the wall, he renounces ownership over the area. With regard to the space in between, if it is four cubits, it is deemed significant in its own right, and if not, it is not significant and is nullified relative to the rest, and it is prohibited to sow there. A similar reasoning applies to the baraita. The stringency is not due to the fact that the partition causes prohibition, but because the partition impedes cultivation of the vineyard.

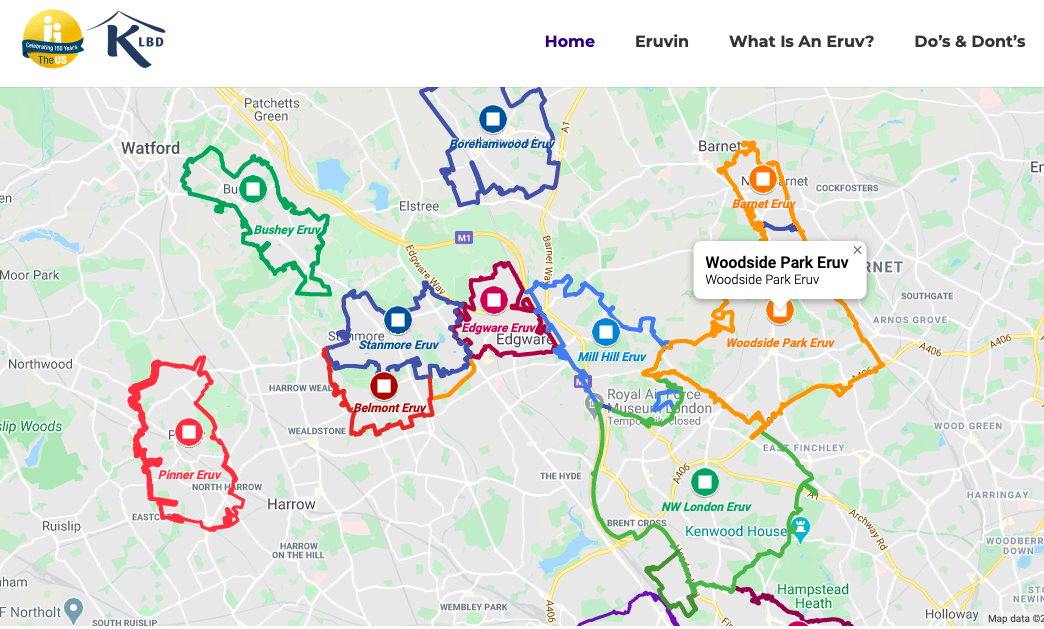

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה: שְׁלֹשָׁה קַרְפֵּיפוֹת זֶה בְּצַד זֶה, וּשְׁנַיִם הַחִיצוֹנִים מְגוּפָּפִים, וְהָאֶמְצָעִי אֵינוֹ מְגוּפָּף, וְיָחִיד בָּזֶה וְיָחִיד בָּזֶה — נַעֲשֶׂה כִּשְׁיָירָא, וְנוֹתְנִין לָהֶן כׇּל צוֹרְכָּן וַדַּאי.

Rav Yehuda said: If there are three enclosures alongside one another, and the two outer ones protrude, i.e., they are wider than the middle one, so that there are partitions on both sides of the breach between them and the middle enclosure, and the middle one does not protrude, and there are no partitions between it and the outer enclosures, as it is totally breached, and there is one person in this one and one person in that one and yet another person in the third enclosure, the people in the enclosures are considered as though they are all living in one large enclosure. Consequently, the legal status of the group becomes like that of a caravan, and one provides them with all the space that they require. In other words, they may use the entire enclosure even if it is very large, just as there are no limits to the size of the enclosed area in which members of a caravan may carry.

אֶמְצָעִי מְגוּפָּף וּשְׁנַיִם הַחִיצוֹנִים אֵינָן מְגוּפָּפִין, וְיָחִיד בָּזֶה וְיָחִיד זֶה [וְיָחִיד בָּזֶה] — אֵין נוֹתְנִין לָהֶם אֶלָּא בֵּית שֵׁשׁ.

However, if the middle enclosure protruded, and the two outer ones did not protrude, i.e., they were narrower than the middle enclosure, so that their entire width was breached into it, and there is one person in this one and one person in that one and yet another in the third, one provides them only an area of six beit se’a, in accordance with the halakha of individuals in a field, who may enclose an area of only two beit se’a per person. As the middle enclosure is larger than the two outer ones, it determines their status, in accordance with the principle stated above, not the other way around. Consequently, the person in the middle enclosure is regarded as though he established residence in only one of the outer enclosures, constituting a group of no more than two, which does not have the legal status of a caravan.

אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: אֶחָד בָּזֶה וְאֶחָד בָּזֶה וּשְׁנַיִם בָּאֶמְצָעִי, מַהוּ? אִי לְהָכָא נָפְקִי — תְּלָתָא הָווּ, וְאִי לְהָכָא נָפְקִי — תְּלָתָא הָווּ.

Based on these assumptions, a dilemma was raised before the Sages: If there is one person in this outer enclosure, and one person in the other outer enclosure, and two people in the middle enclosure, what is the halakha? Is the ruling that if the pair exit to here, one of the outer enclosures, they are three people in one place, and if they exit to there, the other outer enclosure, they are three people in one place, and three people are considered a caravan and provided with all the space they require, as stated above?

אוֹ דִילְמָא: חַד לְהָכָא נָפֵיק, וְחַד לְהָכָא נָפֵיק.

Or perhaps, as one may exit to here and the other may exit to there, in which case there would be no more than two people in each enclosure, they are provided with only two beit se’a per person.

וְאִם תִּימְצֵי לוֹמַר חַד לְהָכָא נָפֵיק וְחַד לְהָכָא נָפֵיק, שְׁנַיִם בָּזֶה וּשְׁנַיִם בָּזֶה וְאֶחָד בְּאֶמְצָעִי מַהוּ? הָכָא וַדַּאי, אִי לְהָכָא נָפֵיק — תְּלָתָא הָווּ, וְאִי לְהָכָא נָפֵיק — תְּלָתָא הָווּ, אוֹ דִילְמָא: אֵימַר לְהָכָא נָפֵיק, וְאֵימַר לְהָכָא נָפֵיק.

And if you say that one may exit to here and one may exit to there, if there were two people in this outer enclosure, and two people in that outer enclosure, and one person in the middle enclosure, what is the halakha? Is the ruling that here, certainly, if he exits to here they are three, and if he exits to there they are likewise three, and consequently they should be provided with all the space they require in any case? Or perhaps, in this case too there is uncertainty, as say that he might exit to here, and say that he might exit to there. As the direction in which he will leave his enclosure is undetermined, they should be provided with only two beit se’a each.

וְהִלְכְתָא בַּעְיַין לְקוּלָּא.

These dilemmas were essentially left unresolved, but the halakha is that these dilemmas are decided leniently, and they are provided with all the space they require in these cases.

אָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא:

Rav Ḥisda said:

גִּידּוּד חֲמִשָּׁה וּמְחִיצָה חֲמִשָּׁה — אֵין מִצְטָרְפִין עַד שֶׁיְּהֵא אוֹ כּוּלּוֹ בְּגִידּוּד אוֹ כּוּלּוֹ בִּמְחִיצָה.

An embankment, a height disparity between two surfaces of five handbreadths, and an additional partition of five handbreadths do not join together to form a partition of ten handbreadths, the minimum height for a partition to enclose a private domain. It is regarded as a partition of ten handbreadths only if the barrier is composed entirely of the embankment or if it is composed entirely of a partition.

מֵיתִיבִי: שְׁתֵּי חֲצֵירוֹת זוֹ לְמַעְלָה מִזּוֹ וְעֶלְיוֹנָה גְּבוֹהָה מִן הַתַּחְתּוֹנָה עֲשָׂרָה טְפָחִים, אוֹ שֶׁיֵּשׁ בָּהּ גִּידּוּד חֲמִשָּׁה וּמְחִיצָה חֲמִשָּׁה — מְעָרְבִין שְׁנַיִם, וְאֵין מְעָרְבִין אֶחָד. פָּחוֹת מִכָּאן מְעָרְבִין אֶחָד, וְאֵין מְעָרְבִין שְׁנַיִם!

The Gemara raises an objection from a baraita: If there were two courtyards, one above the other, and the upper one was ten handbreadths higher than the lower one, or if it had an embankment of five handbreadths and a partition of five handbreadths, the two courtyards are considered separate domains and they establish two eiruvin, one for each courtyard, and they do not establish one eiruv. If the height disparity was less than ten handbreadths, the two areas are considered a single domain, and they establish one eiruv and they do not establish two eiruvin.

אָמַר (רַב): מוֹדֶה רַב חִסְדָּא בַּתַּחְתּוֹנָה, הוֹאִיל וְרוֹאֶה פְּנֵי עֲשָׂרָה. אִי הָכִי: תַּחְתּוֹנָה — תְּעָרֵב שְׁנַיִם וְלֹא תְּעָרֵב אֶחָד, עֶלְיוֹנָה — לֹא תְּעָרֵב לֹא אֶחָד וְלֹא שְׁנַיִם.

Rav said: Rav Ḥisda concedes that an embankment and a partition combine with regard to the lower courtyard, since it faces a wall of ten, i.e., there is a full partition of ten handbreadths before its residents. The Gemara raises a difficulty: If so, according to this reasoning, the residents of the lower courtyard, from whose perspective there is a valid partition, should establish two eiruvin, i.e., an independent eiruv, and do not establish one eiruv together with the upper courtyard, while the residents of the upper courtyard establish neither one eiruv nor two. The residents of the upper courtyard neither establish an eiruv on their own, as it is breached into the lower one, nor can they establish an eiruv together with the lower courtyard, because the latter is separated from it.

אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר עוּלָּא: כְּגוֹן שֶׁהָיְתָה עֶלְיוֹנָה מְגוּפֶּפֶת עַד עֶשֶׂר אַמּוֹת.

Rabba bar Ulla said: The baraita is referring to a case where the upper courtyard had full-fledged ten-handbreadth-high walls that protruded on both sides of the section of the partition that was merely five handbreadths high, a protrusion that extended up to ten cubits. In this case, the upper courtyard is properly enclosed by a partition ten handbreadths high, while the section that is only five handbreadths high is deemed an entrance. Consequently, even the residents of the upper courtyard can establish an eiruv on their own. But the two courtyards cannot be merged by a single eiruv, because the lower courtyard is enclosed by a partition from which there is no entrance to the upper courtyard.

אִי הָכִי, אֵימָא סֵיפָא: פָּחוֹת מִכָּאן — מְעָרְבִין אֶחָד וְאֵין מְעָרְבִין שְׁנַיִם, אִי בָּעֲיָא — חַד תְּעָרֵב, אִי בָּעֲיָא — תְּרֵי תְּעָרֵב!

The Gemara raises a difficulty: If so, say the latter clause of that same baraita: If the height disparity was less than ten handbreadths, they are considered a single domain, and the residents therefore establish one eiruv, but they do not establish two eiruvin. According to the explanation suggested above, that there is a partition ten handbreadths high between the courtyards with an entrance of sorts between them, if they wish, they establish one eiruv, and if they wish, they establish two eiruvin. That is the halakha in a case of two courtyards with an entrance between them.

אָמַר רַבָּה בְּרֵיהּ דְּרָבָא: כְּגוֹן שֶׁנִּפְרְצָה הַתַּחְתּוֹנָה בִּמְלוֹאָהּ לָעֶלְיוֹנָה.

Rabba, son of Rava, said: The baraita refers to a case where the lower courtyard was fully breached into the upper one, i.e., the gap in the wall spanned the entire width of the lower courtyard. In that case, the residents of the lower courtyard establish a joint eiruv with the upper courtyard; however, they may not establish an eiruv of their own, in accordance with the mishna in which we learned that if a large courtyard is breached into a smaller one, it is permitted for the residents of the large courtyard to carry, but it is prohibited for the residents of the small one to do so.

אִי הָכִי, תַּחְתּוֹנָה חַד תְּעָרֵב, תְּרֵי לָא תְּעָרֵב. עֶלְיוֹנָה, אִי בָּעֲיָא — תְּרֵי תְּעָרֵב, אִי בָּעֲיָא — חַד תְּעָרֵב.

The Gemara raises a difficulty: If so, the halakha should be that the residents of the lower courtyard establish one eiruv together with the upper one, but they do not establish two eiruvin, i.e., the residents cannot establish an independent eiruv for their courtyard. However, with regard to the upper one, if its residents wish, they establish one eiruv together with the lower courtyard, and if they wish, they establish two eiruvin. The residents of the upper courtyard can establish an independent eiruv for their courtyard, as the larger courtyard renders it prohibited for the residents of the smaller courtyard to carry, but not vice versa.

אִין הָכִי נָמֵי. וְכִי קָתָנֵי ״פָּחוֹת מִכָּאן מְעָרְבִין אֶחָד וְאֵין מְעָרְבִין שְׁנַיִם״, אַתַּחְתּוֹנָה.

The Gemara answers: Yes, it is indeed so; that is the halakha. And when the baraita teaches: If the height disparity was less than ten handbreadths, the residents establish one eiruv, but they do not establish two eiruvin, this statement is not referring to both courtyards, but only to the lower one.

דְּרַשׁ מָרִימָר: גִּידּוּד חֲמִשָּׁה וּמְחִיצָה חֲמִשָּׁה — מִצְטָרְפִין. אַשְׁכְּחֵיהּ רָבִינָא לְרַב אַחָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרָבָא, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: תָּנֵי מָר מִידֵּי בִּמְחִיצָה? אֲמַר לֵיהּ: לָא. וְהִלְכְתָא: גִּידּוּד חֲמִשָּׁה וּמְחִיצָה חֲמִשָּׁה מִצְטָרְפִין.

Mareimar taught: An embankment of five handbreadths and an additional partition of five handbreadths above it combine to form a partition of ten handbreadths. Ravina met Rav Aḥa, son of Rava, and said to him: Has the Master taught anything with regard to this partition, whether it is effective or not? He said to him: No. The Gemara concludes: The halakha is that an embankment of five handbreadths and a partition of five handbreadths combine to form an effective partition of ten handbreadths.

בָּעֵי רַב הוֹשַׁעְיָא: דָּיוֹרִין הַבָּאִין בְּשַׁבָּת, מַהוּ שֶׁיֵּאָסְרוּ?

Rav Hoshaya raised a dilemma: What is the ruling with regard to residents who arrive on Shabbat, i.e., who join the residents of a courtyard on Shabbat, e.g., if the wall between two courtyards collapsed on Shabbat so that new residents arrive in one courtyard from the other. Had these people arrived before Shabbat they would have rendered it prohibited for the residents to carry in the courtyard unless they participated with the original residents in their eiruv. Do these residents render it prohibited for the original residents to carry in the courtyard, even if they arrive on Shabbat itself?

אָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא, תָּא שְׁמַע: חָצֵר גְּדוֹלָה שֶׁנִּפְרְצָה לִקְטַנָּה — הַגְּדוֹלָה מוּתֶּרֶת וְהַקְּטַנָּה אֲסוּרָה, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁהִיא כְּפִתְחָהּ שֶׁל גְּדוֹלָה. אָמַר רַבָּה: אֵימַר מִבְּעוֹד יוֹם נִפְרְצָה.

Rav Ḥisda said: Come and hear a resolution to the dilemma from the mishna: With regard to a large courtyard that was breached into a small courtyard, it is permitted for the residents of the large courtyard to carry, but it is prohibited for the residents of the small one to do so. It is permitted to carry in the large courtyard because the breach is regarded like the entrance of the large courtyard. Apparently, even if the breach occurred on Shabbat, it is prohibited for the residents of the small courtyard to carry. Rabba said: Say that the mishna is dealing with a case where it was breached while it was still day, i.e., on Friday. However, there is no prohibition if the breach occurred on Shabbat itself.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי: לָא תֵּימָא מָר ״אֵימַר״, אֶלָּא וַדַּאי מִבְּעוֹד יוֹם נִפְרְצָה. דְּהָא מָר הוּא דְּאָמַר, בְּעַי מִינֵּיהּ מֵרַב הוּנָא וּבְעַי מִינֵּיהּ מֵרַב יְהוּדָה: עֵירַב דֶּרֶךְ הַפֶּתַח וְנִסְתַּם הַפֶּתַח, עֵירַב דֶּרֶךְ חַלּוֹן וְנִסְתַּם הַחַלּוֹן, מַהוּ? וְאָמַר לִי: שַׁבָּת, כֵּיוָן שֶׁהוּתְּרָה הוּתְּרָה.

Abaye said to him: The Master should not state: Say, indicating that it is possible to explain the mishna in this manner. Rather, the mishna is certainly referring to a case where the courtyard was breached while it was still day. As Master, you are the one who said: I raised a dilemma before Rav Huna, and I raised a dilemma before Rav Yehuda: If one established an eiruv to join one courtyard to another via a certain opening, and that opening was sealed on Shabbat, or if one established an eiruv via a certain window, and that window was sealed on Shabbat, what is the halakha? May one continue to rely on this eiruv and carry from one courtyard to the other via other entrances? And he said to me: Once it was permitted to carry from courtyard to courtyard at the onset of Shabbat, it was permitted and remains so until the conclusion of Shabbat. According to this principle, if a breach that adds residents occurs on Shabbat, the breach does not render prohibited activities that were permitted when Shabbat began.

אִתְּמַר, כּוֹתֶל שֶׁבֵּין שְׁתֵּי חֲצֵירוֹת שֶׁנָּפַל, רַב אָמַר: אֵין מְטַלְטְלִין בּוֹ אֶלָּא בְּאַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת.

It is stated that amora’im disagreed: With regard to a wall between two courtyards, whose residents did not establish a joint eiruv, that collapsed on Shabbat, Rav said: One may carry in the joint courtyard only within four cubits, as carrying in each courtyard is prohibited due to the other, because they did not establish an eiruv together. Rav does not accept the principle that an activity that was permitted at the start of Shabbat remains permitted until the conclusion of Shabbat.

וּשְׁמוּאֵל אָמַר:

And Shmuel said: