This month’s learning is sponsored by Beth Balkany in honor of their granddaughter, Devorah Chana Serach Eichel. “May she grow up to be a lifelong learner.”

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

This month’s learning is sponsored by Beth Balkany in honor of their granddaughter, Devorah Chana Serach Eichel. “May she grow up to be a lifelong learner.”

Delve Deeper

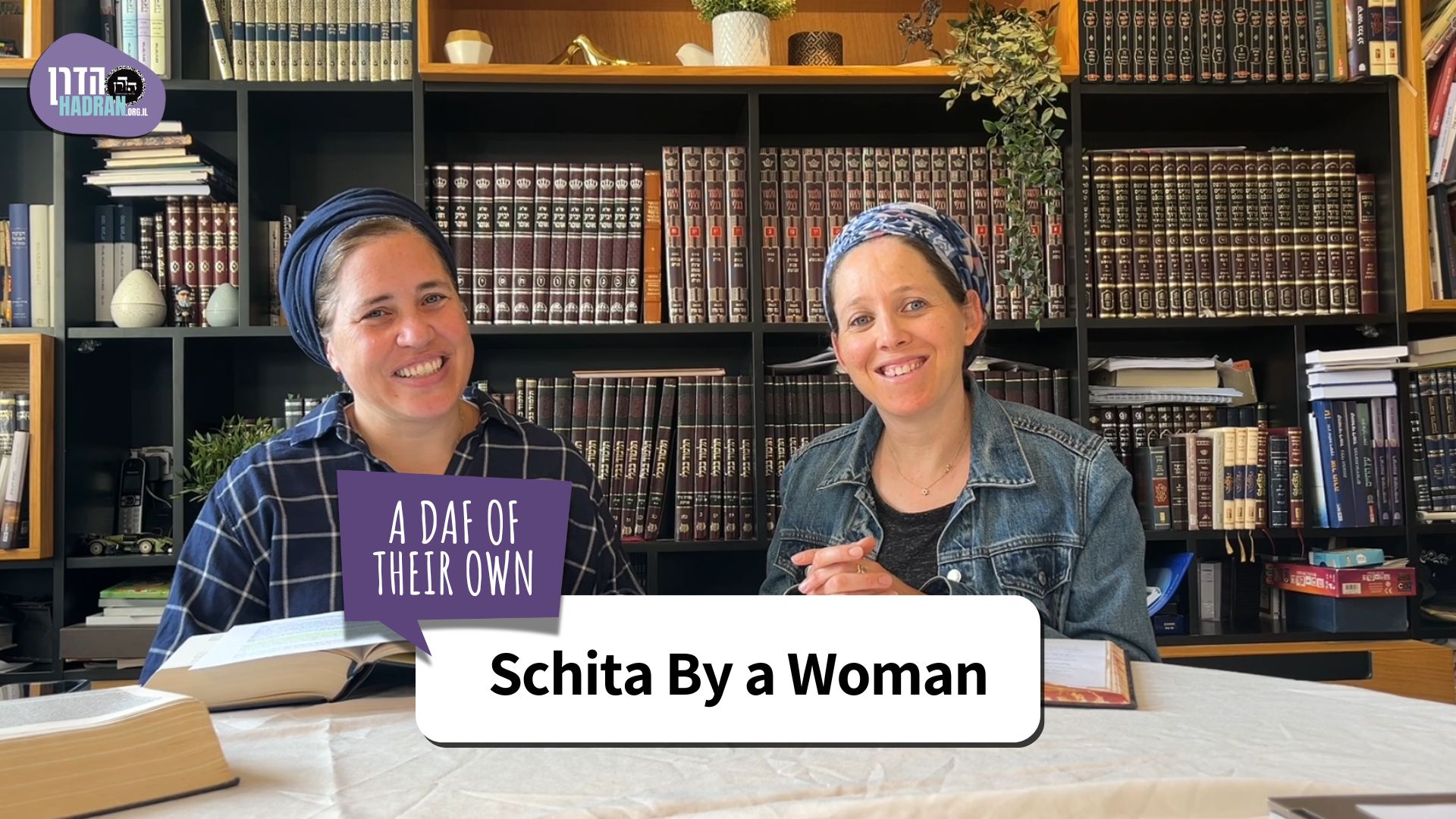

Broaden your understanding of the topics on this daf with classes and podcasts from top women Talmud scholars.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Nazir 12

״צֵא וְקַדֵּשׁ לִי אִשָּׁה״ סְתָם — אָסוּר בְּכׇל הַנָּשִׁים שֶׁבָּעוֹלָם. חֲזָקָה שָׁלִיחַ עוֹשֶׂה שְׁלִיחוּתוֹ, וְכֵיוָן דְּלָא פָּרֵישׁ לֵיהּ, הָא לָא יָדַע הֵי נִיהוּ קַדֵּישׁ לֵיהּ.

Go out and betroth a woman for me, without specifying a particular woman; from that moment onward the one who appointed the agent is forbidden to all the women in the world until he finds out which woman the agent betrothed. There is a presumption that an agent performs his assigned agency and that he has betrothed a woman for him, and since the agent did not clarify to him which woman he chose, he therefore does not know which woman is the one betrothed to him. If he now betroths another woman, it is possible that she is the daughter, sister, or mother of the one his agent betrothed on his behalf and is therefore forbidden to him.

אֵיתִיבֵיהּ רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ לְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: קֵן סְתוּמָה שֶׁפָּרְחָה גּוֹזָל אֶחָד מֵהֶן לַאֲוִיר הָעוֹלָם, אוֹ שֶׁפָּרְחָה לְבֵין חַטָּאוֹת הַמֵּתוֹת, אוֹ שֶׁמֵּת אֶחָד מֵהֶן — יִקַּח זוּג לַשֵּׁנִי.

Reish Lakish raised an objection to Rabbi Yoḥanan from a mishna (Kinnim 2:1): With regard to an impure person who comes to undergo his purification process, and for this purpose set aside an unspecified nest, meaning a pair of turtledoves or pigeons, to use for his offerings. One is to be a burnt-offering and one is to be a sin-offering, and he had not yet specified which bird will be used for which offering. If one fledgling of the pair flew away and escaped to the open air of the world, or if it flew among birds invalidated for sin-offerings that have been left to die, or if one of them died, in each of these cases the owner of the nest purchases a partner for the second, i.e., remaining, bird. At that point he may decide which is for a sin-offering and which is for a burnt-offering.

וְאִילּוּ קֵן מְפוֹרֶשֶׁת — אֵין לוֹ תַּקָּנָה.

But if a fledgling flew away or died from a specified nest, after the owner had designated which bird would be used for which offering, and it is not known which bird escaped, it has no means of remedy. This is because he does not know whether the remaining fledgling is for a burnt-offering or a sin-offering.

וְאִילּוּ שְׁאָר קִינִּין בְּעָלְמָא מִיתַּקְּנָן. וְאַמַּאי? לֵימָא כׇּל חֲדָא וַחֲדָא דִּלְמָא הַאי נִיהוּ!

Reish Lakish infers: But generally, other nests belonging to other people are fit; there is no concern with regard to them. Reish Lakish states his objection to the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan: According to your opinion that there is a concern that each woman might be a relative of the woman the agent betrothed, then why should the halakha with regard to nests be so? Let us likewise say with regard to each and every fledgling bird in the world that perhaps this is the one that was consecrated and flew away. How can anyone ever use a bird for their own offering, as it may be the bird that flew away from someone else’s nest?

אֲמַר לֵיהּ: קָאָמֵינָא אֲנָא אִשָּׁה דְּלָא נָיְידָא, וְאָמְרַתְּ לִי אַתְּ אִיסּוּרָא דְּנָיֵיד?

Rabbi Yoḥanan said to Reish Lakish: I state my opinion that there is a concern for other women only with regard to a woman, who does not move but is fixed in her home. An unidentified item is presumed to have the same legal status as the majority of items like it, and there is no concern that it may be forbidden, even if there are some forbidden items like it. However, if this unidentified item was fixed in its place, there is an equal presumption that it may belong to the class of similar permitted items or to the class of similar forbidden items. Consequently, all women in the world are forbidden to him, as there is an equal presumption that she may or may not be a relative of the woman that the agent betrothed to him. And you speak to me of a prohibition that moves and is not fixed. Since the fledgling bird is not fixed in one spot, the majority is followed and the minority is ignored.

וְכִי תֵּימָא: הָכָא נָמֵי נָיֵיד, אֵימוֹר בְּשׁוּקָא אַשְׁכַּח וְקַדֵּישׁ, הָתָם הָדְרָא לְנִיחוּתָא, גַּבֵּי קֵן מִי הָדְרָא?

And if you would say: Here too, she moves, since it is possible to say that the agent found the woman in the marketplace and betrothed her there to the one who appointed the agent, so the prohibited woman was not in a fixed location? Nevertheless, there she eventually returns to her place of rest, i.e., her home, and is therefore considered to be fixed. Conversely, with regard to a nest, does the fledgling return to a fixed place? Since it does not, the assumption is that any bird has the status of the majority of birds in the world, which have not been consecrated as offerings.

אָמַר רָבָא: וּמוֹדֶה רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן בְּאִשָּׁה שֶׁאֵין לָהּ לֹא בַּת, וְלֹא בַּת בַּת, וְלֹא בַּת בֵּן, וְלֹא אֵם, וְלֹא אֵם אֵם, וְלֹא אָחוֹת. וְאַף עַל פִּי שֶׁהָיְתָה לָהּ אָחוֹת וְנִתְגָּרְשָׁה לְאַחַר מִכָּאן, דְּהָהִיא שַׁרְיָא.

Rava said: And Rabbi Yoḥanan concedes that with regard to a woman who does not have a daughter, nor a daughter of a daughter, nor a daughter of a son, nor a mother, nor a mother of a mother, nor a sister who was single when he appointed the agent, that the one who appointed the agent may betroth her. There is no concern that the agent might have betrothed a relative that would now render such a woman forbidden. And even though she had, when he appointed the agent, a married sister, or daughter, or other female relative, and she was later divorced, Rabbi Yoḥanan concedes that this woman whom he wishes to now marry is permitted.

מַאי טַעְמָא — דִּבְהָהִיא שַׁעְתָּא דְּקָא אָמַר לֵיהּ, הֲוָה נְסִיבָן לְגַבְרֵי. כִּי מְשַׁוֵּי שָׁלִיחַ — בְּמִילְּתָא דְּקָיְימָא קַמֵּיהּ. בְּמִילְּתָא דְּלָא קָיְימָא קַמֵּיהּ — לָא מְשַׁוֵּי שָׁלִיחַ.

What is the reason for this? It is that at that moment, when he told the agent to go betroth a woman on his behalf, these women were married to men. There is a principle that when one appoints an agent, he does so only with regard to a matter present before him. In other words, he instructs his agent to betroth a woman who is available at that time, but he does not appoint an agent with regard to a matter that is not present before him. Consequently, even if the agent betrothed one of the relatives of the woman after they were divorced, the betrothal would not take effect because he was not authorized to betroth them, and therefore the one who appointed the agent is permitted to the woman.

תְּנַן: ״הֲרֵינִי נָזִיר וְעָלַי לְגַלֵּחַ נָזִיר״, וְשָׁמַע חֲבֵירוֹ וְאָמַר: ״וַאֲנִי, וְעָלַי לְגַלֵּחַ נָזִיר״, אִם הָיוּ פִּקְחִין — מְגַלְּחִין זֶה אֶת זֶה, וְאִם לָאו — מְגַלְּחִין נְזִירִים אֲחֵרִים. בִּשְׁלָמָא בָּתְרָאָה — אִיכָּא קַדְמָאָה קַמֵּיהּ. אֶלָּא קַדְמָאָה — מִי אִיכָּא בָּתְרָאָה קַמֵּיהּ?

The Gemara now proceeds to raise a difficulty against this last argument from the mishna: We learned in the mishna that if one says: I am hereby a nazirite and it is incumbent upon me to shave a nazirite, and another heard him and said: And I am hereby a nazirite, and it is incumbent upon me to shave a nazirite, if they are perspicacious they shave each other; and if not, they shave other nazirites. According to the reasoning that one takes into account only that which is possible at the time, the following difficulty arises: Granted, the last person has the first one before him and may have had in mind to volunteer to pay for the other’s offerings; but with regard to the first person, is the last one before him? When the first one stated his vow, the other one was not yet a nazirite, and he could not have been taking him into account when he vowed to pay for the offerings of another. How can paying for the offerings of the second nazirite be considered a fulfillment of his vow?

אֶלָּא הָכִי קָאָמַר: אִי מַשְׁכַּחְנָא דְּהָוֵי נָזִיר, אֲגַלְּחֵיהּ. הָכָא נָמֵי, הָכִי קָאָמַר לֵיהּ: אִי מַשְׁכַּחַתְּ דְּמִיגָּרְשָׁה, קַדֵּישׁ לִי.

Rather, it can be explained that this is what he is saying: If I find someone who becomes a nazirite, I will shave him. Here too, in the case of betrothal, this is what the one who appointed the agent is saying to the agent: Even if the woman you find is married at this moment but when you come to her you discover that she has been divorced in the meantime, betroth her to me. If so, he would be prohibited from marrying her sister, contrary to the ruling of Rava.

אָמְרִי: לָא מְשַׁוֵּי אִינִישׁ שָׁלִיחַ אֶלָּא בְּמִילְּתָא דְּמָצֵי עָבֵיד הַשְׁתָּא, בְּמִילְּתָא דְּלָא מָצֵי עָבֵיד לֵיהּ הַשְׁתָּא — לָא מְשַׁוֵּי.

The Gemara rejects this comparison: The Sages say that there is a distinction between the two cases: A person appoints an agent only for a matter that he himself can perform now, at the time of the appointment, but for a matter that he cannot perform now, he does not appoint an agent. Consequently, the agent cannot betroth a woman who was married at the time of his appointment. The one who appointed the agent may therefore marry the sister of the recently divorced woman, as stated by Rava.

וְלָא? תָּא שְׁמַע, הָאוֹמֵר לְאַפּוֹטְרוֹפּוֹס שֶׁלּוֹ: ״כׇּל נְדָרִים שֶׁתִּדּוֹר אִשְׁתִּי מִכָּאן עַד שֶׁאָבוֹא מִמָּקוֹם פְּלוֹנִי — הָפֵר לָהּ״, וְהֵפֵר לָהּ, יָכוֹל יְהוּ מוּפָרִין — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״אִישָׁהּ יְקִימֶנּוּ וְאִישָׁהּ יְפֵרֶנּוּ״, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי יֹאשִׁיָּה. וְרַבִּי יוֹנָתָן אוֹמֵר: מָצִינוּ בְּכׇל מָקוֹם שֶׁשְּׁלוּחוֹ שֶׁל אָדָם כְּמוֹתוֹ.

The Gemara asks another question on the ruling of Rava: And can one not appoint an agent to betroth a woman in this manner? Come and hear a baraita that indicates the contrary: One who says to the steward [apotropos] of his affairs: All vows that my wife will vow from now until I come from such and such a place, nullify for her, and the steward nullified them for her, one might have thought they are nullified. Therefore, the verse states: “Her husband sustains the vow and her husband nullifies the vow” (Numbers 30:14); this is the statement of Rabbi Yoshiya. The repetition of “husband” teaches that it is the husband alone who may nullify his wife’s vows. And Rabbi Yonatan says: We have found in all places that the legal status of a person’s agent is like that of himself. Therefore, a steward, who serves as the husband’s agent, may nullify the wife’s vows.

טַעְמָא דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״אִישָׁהּ יְקִימֶנּוּ וְאִישָׁהּ יְפֵירֶנּוּ״, הָא לָאו הָכִי — אַפּוֹטְרוֹפּוֹס מֵיפֵר. וְאִילּוּ גַּבֵּי דִידֵיהּ תַּנְיָא: הָאוֹמֵר לְאִשְׁתּוֹ ״כׇּל נְדָרִים שֶׁתִּדּוֹרִי מִכָּאן וְעַד שֶׁאָבֹא מִמָּקוֹם פְּלוֹנִי יְהוּ קַיָּימִין״ — לֹא אָמַר כְּלוּם. ״הֲרֵי הֵן מוּפָרִין״, רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר אוֹמֵר: מוּפָר, וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: אֵינוֹ מוּפָר.

Even according to Rabbi Yoshiya, who maintains that the steward cannot nullify her vows, the reason is that the Merciful One states in the Torah: “Her husband sustains the vow and her husband nullifies the vow,” but if it were not so, the steward could nullify even the future vows of the wife. However, with regard to the husband himself it is taught in a mishna (Nedarim 75a): One who says to his wife: All vows that you will vow from now until I come from such and such a place shall be ratified, he has not said anything. However, if a husband says: All vows that you will vow from now until I come from such and such a place, they are hereby nullified, Rabbi Eliezer says: It is nullified, and the Rabbis say: It is not nullified.

קָא סָלְקָא דַּעְתִּין כִּי אָמַר רַבִּי יֹאשִׁיָּה — אַלִּיבָּא דְרַבָּנַן דְּאָמְרִי לָא מָצֵי מֵיפֵר, וְאִי לָאו דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״אִישָׁהּ יְקִימֶנּוּ וְאִישָׁהּ יְפֵירֶנּוּ״, אַפּוֹטְרוֹפּוֹס הֲוָה מֵיפַר.

The Gemara finishes the question: It enters our mind to say that when Rabbi Yoshiya said that the steward cannot nullify the vows, he spoke in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis, who say that the husband is not able to nullify her vows ahead of time, and yet, even according to their approach, if the Merciful One had not stated in the Torah: “Her husband sustains the vow and her husband nullifies the vow” the steward would be able to nullify such vows. This proves that one can appoint an agent for something he himself cannot do at the time, which contradicts the statement of Rava.

וְדִלְמָא אַלִּיבָּא דְּרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר, דְּאָמַר מָצֵי מֵיפַר! אִי הָכִי, לְמָה לִי לְשַׁוּוֹיֵי שָׁלִיחַ? לֵיפַר לַהּ אִיהוּ! קָסָבַר דִּלְמָא מִשְׁתְּלֵינָא, אוֹ רָתַחְנָא, אוֹ מִיטְּרִידְנָא.

The Gemara rejects this: And perhaps Rabbi Yoshiya spoke in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer, who says the husband can nullify the vows ahead of time, and it is for this reason that he can appoint the steward to do the same. The Gemara rejects this: If so, why do I need to make him into an agent; let him nullify the future vows for her before he sets out on his journey. The Gemara answers: He thinks, perhaps I will forget, or become angry, or be occupied with other matters when I am about to set out on my journey. This is why he appoints an agent to nullify the vows on his behalf, and no proof can be derived from this baraita.

מַתְנִי׳ ״הֲרֵי עָלַי לְגַלֵּחַ חֲצִי נָזִיר״, וְשָׁמַע חֲבֵירוֹ וְאָמַר ״וַאֲנִי עָלַי לְגַלֵּחַ חֲצִי נָזִיר״ — זֶה מְגַלֵּחַ נָזִיר שָׁלֵם, וְזֶה מְגַלֵּחַ נָזִיר שָׁלֵם, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי מֵאִיר. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: זֶה מְגַלֵּחַ חֲצִי נָזִיר, וְזֶה מְגַלֵּחַ חֲצִי נָזִיר.

MISHNA: If one says: It is incumbent upon me to shave half a nazirite, i.e., he is vowing to pay half the costs of a nazirite’s offerings, and another heard and said: And I, it is incumbent upon me to shave half a nazirite, this one shaves a whole nazirite and that one shaves a whole nazirite, i.e., each pays the full cost of a nazirite’s offerings; this is the statement of Rabbi Meir, since there is no such entity as half a nazirite. And the Rabbis say: This one shaves half a nazirite and that one shaves half a nazirite; they may join together to pay for the offerings of one nazirite.

גְּמָ׳ אָמַר רָבָא: הַכֹּל מוֹדִים, כֹּל הֵיכָא דְּאָמַר ״חֲצִי קׇרְבָּנוֹת נָזִיר עָלַי״ — חֲצִי קׇרְבָּן מַיְיתֵי. ״קׇרְבְּנוֹת חֲצִי נָזִיר עָלַי״ — כּוּלֵּיהּ קׇרְבָּן בָּעֵי אֵיתוֹיֵי. מַאי טַעְמָא — דְּהָא לָא אַשְׁכְּחַן נְזִירוּת לְפַלְגָא.

GEMARA: With regard to this dispute, Rava said: All concede that whenever one said: Half of the offerings of a nazirite are incumbent upon me, he brings half of the offerings, since he vowed to pay only that amount. Also, everyone agrees that if he said: The offerings of half a nazirite are incumbent upon me, he needs to bring all of the offerings of a nazirite. What is the reason that he must bring all of the offerings of a nazirite? It is that we have not found such an entity as half a naziriteship. If one vowed to be half a nazirite, he is a full nazirite.

וְכִי פְּלִיגִי, בְּלִישָּׁנָא דְמַתְנִיתִין פְּלִיגִי. רַבִּי מֵאִיר סָבַר: כֵּיוָן דְּאָמַר ״הֲרֵי עָלַי״ — אִיחַיַּיב אַכּוּלֵּיהּ קׇרְבַּן נְזִירוּת, וְכִי קָאָמַר חֲצִי נְזִירוּת — לָאו כֹּל כְּמִינֵּיהּ. וְרַבָּנַן סָבְרִי: נֶדֶר וּפֶתַח עִמּוֹ הוּא.

And when they disagree, it is only in a case of one who used the precise wording of the mishna. Rabbi Meir holds that once he said: It is incumbent upon me, he is obligated in all of the naziriteship offerings, and when he later says: Half a naziriteship, it is not in his power to uproot his first obligation. And the Rabbis hold that it is a vow with its inherent opening. By saying he had only half the offerings of a nazirite in mind from the outset, he has nullified his own vow.

מַתְנִי׳ ״הֲרֵינִי נָזִיר לִכְשֶׁיִּהְיֶה לִי בֵּן״, וְנוֹלָד לוֹ בֵּן — הֲרֵי זֶה נָזִיר. נוֹלַד לוֹ בַּת, טוּמְטוּם, וְאַנְדְּרוֹגִינוֹס — אֵינוֹ נָזִיר. אִם אָמַר ״כְּשֶׁיִּהְיֶה לִי וָלָד״ — אֲפִילּוּ נוֹלַד לוֹ בַּת, טוּמְטוּם, וְאַנְדְּרוֹגִינוֹס — הֲרֵי זֶה נָזִיר.

MISHNA: If one said: I am hereby a nazirite when I will have a son, and a son was born to him, he is a nazirite. If a daughter, a tumtum, or a hermaphrodite [androginos] is born to him, he is not a nazirite, since a son was not born to him. However, if he says: I am hereby a nazirite when I will have a child, then even if a daughter, a tumtum, or a hermaphrodite is born to him, he is a nazirite.