You stubborn mule! You stupid donkey! What did these poor animals do to deserve such abuse? Nothing, it turns out. Mules and donkeys serve people loyally and in return they are stereotyped as foolish, cranky and stubborn. Where do the donkey and the mule (hamor and pered) appear in our Gemara and what role do they play in Jewish texts and laws?

The donkey is the quintessential animal, cited whenever we have laws concerning domesticated beasts:

“If so, why are all of the above halakhot stated in the Torah only in reference to an ox or a donkey? Rather, the reason is that the verse speaks of a common scenario,” (Mishnah Bava Kama 5:7)

What was the main purpose of the donkey? The Gemara offers two possibilities:

“Ulla says: The dispute in the mishna is referring to the donkey’s sack and the saddlebag [disakkaya] and the kumni. As the first tanna holds: An ordinary donkey is used primarily for riding. And Naḥum the Mede holds: An ordinary donkey is used for carrying burdens. But the saddle (ukaf) and the saddlecloth(mirdaat), the harness(kilkli) and the saddle band (habak), everyone agrees that they are sold,” (Bava Batra 78a)

Is a donkey meant for riding only or also for carrying burdens? Everyone agrees that a donkey is meant for riding so the saddle and its accessories are included. But we have a dispute over whether its primary purpose is carrying things, in which case the saddlebags would be included as well.

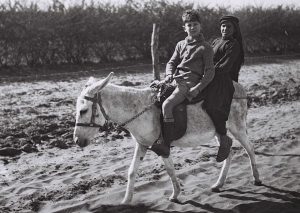

Zoltan Kluger, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Donkeys were domesticated thousands of years ago from wild Arabian asses. Some suggest that the name hamor חמור comes from hamar, the color red, since they are a reddish brown. They proved very useful to people since they could carry heavy burdens and would eat things that were less desirable to people like barley and carobs. The Torah invokes the donkey when it discusses helping up an animal that has fallen under its heavy weight:

“When you see the donkey of your enemy lying under its burden and would refrain from raising it, you must nevertheless help raise it”. (Shmot 23:5)

A donkey carrying a load of matza in Tzfat

Zoltan Kluger Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The donkey was part of every household and had the right to rest on Shabbat just like his master:

“but the seventh day is a Sabbath of your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your ox or your donkey, or any of your cattle, or the stranger in your settlements.” (Devarim 5:14)

As we see from our Gemara, donkeys were also used for riding. We have many examples in Tanakh of donkeys and their riders, among them Abraham, Moses, Bilaam and the Messiah. Rashi, in an oft-misunderstood comment, says that the donkey that Moses took down to Egypt (Shmot 4:20) was the same donkey saddled by Abraham when he took Isaac to Mount Moriah and the same one that will be the vehicle of the Messiah. Rather than a very long-lived donkey, Rashi means that all three are part of the process of the redemption of the Jewish people.

The Messiah’s donkey is perhaps the most famous, and the prophet Zechariah’s image has often been invoked by Jews and Christians alike:

“Lo, your king is coming to you. He is victorious, triumphant, Yet humble עני, riding on a donkey,” (Zechariah 9:9)

The commentaries explain that עני here does not mean poor but rather modest, like the word ענו The donkey invokes the same idea– the Messiah will not come riding on a horse, the beast of kings and of warfare, or even on a mule but on the very humble donkey.

The humility and patience of the donkey is perhaps why Jacob’s son Issachar is blessed to be like one:

“Issachar is a strong-boned donkey, Crouching among the sheepfolds.” (Bereshit 49:14)

At some point donkeys become associated not with humility but with physicality and a lack of understanding, the חמור becomes the stand-in for the חומר, the material and not spiritual side of being. For this reason, Gentiles are sometimes referred to as donkeys in Rabbinic texts and donkeys also get a reputation for stupidity. A late midrash says that if you can find a donkey going up a ladder, you can find wisdom in fools; in another words, both of these things are impossible. This association of the donkey and the fool is not accidental – lots of animals cannot climb ladders, the donkey was chosen because it was considered to be not so bright.

A donkey might not be able to climb a ladder but he can climb steps

Willem van de Poll, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

This phrase had a curious afterlife. In medieval Ashkenaz, scribes started writing at the end of a copied text not only their names but some version of this ditty:

חזק ונתחזק הסופר לא יוזק לא היום ולא לעולם עד שיעלה חמור בסולם אשר יעקב אבינו חלם

Be strong and strengthened, may no harm befall the scribe not today and not forever, until the donkey ascends the ladder that our father Jacob dreamed about

See here for some great examples of this phenomenon: https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2020/03/until-the-donkey-ascends-the-ladder-hebrew-scribal-formulae.html

A mule פרד is a related but different animal. It is the offspring of a male donkey and a female horse and so it is large like a horse but has the qualities of strength and perseverance of the donkey. Its name comes from the word to separate – it stands alone, unable to breed. Jews are forbidden to breed mules, since this is kilayim, mixed breeding, but they can benefit from them. The Mishnah on Bava Batra 77 mentions mules that pull a carriage and mules seem to have been used by a higher class of people. Avshalom, King David’s rebellious son, rides a mule and indeed meets his end when the mule takes him under a low-hanging tree and he gets caught by his hair (Shmuel II 18:9). When Solomon is taken to be crowned David’s successor he is seated on a mule(Kings I 1:33)

In modern times, mules played a part in the Zionist story. Jews such as Joseph Trumpeldor wanted to join the British army during World War I, both to help defeat the Ottoman Turks and to gain combat experience. The British did not allow them to fully join up since most of them were foreign nationals. However, they created a volunteer corps to bring water to the troops in Gallipoli. Naturally the water was carried by mules and so the Zion Mule Corps was born. The ZMC, commanded by Colonel John Patterson, a strong philo-Semite, served in the battle at Gallipoli and after that the Jewish Legion was created.

Mule from Turkey

Zeynel Cebeci, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Donkeys and mules may not really be stubborn but Jews certainly are.