Can an impure person enter the Levite area of the Temple? This is the Gemara’s question on daf 44 and 45 of Nazir. Impurity of any kind, and certainly a dead body itself would seem to be forbidden in the Temple but then Abaye offers an interesting twist on this question:

“and not only one impure from a corpse, but even a corpse itself may be brought inside the Levite camp, as it is stated: “And Moses took the bones of Joseph with him” (Exodus 13:19). What is the meaning of “with him”? within Moses’s boundary, with him in the Levite camp” (Nazir 45a)

Moses lived in the Levite camp in the desert and he had a Joseph’s bones with him all the time, therefore it would seem fine for an impure person to enter the Levite camp. But why was Moses schlepping bones around the desert? The story of Joseph’s bones is a fascinating one that continues to this day.

At the very end of the book of Bereshit, Joseph, second in command in Egypt, makes his brothers promise that when they will be freed from Egypt, they will take his bones and rebury them back in the land of Canaan. Joseph is aware that his brothers will not have the political clout to do what he himself did for his father Jacob: bring a huge funeral cortege to Hebron under the auspices of the Egyptian government. In fact, his dying request seems to indicate dark days ahead for the Israelites in Egypt, when they will be denied freedom of movement. Only when God redeems them, will they be able to fulfill his request.

And indeed, the Israelites’ fortunes decline rapidly and they are enslaved in Egypt for centuries. When the time finally comes to leave, only one man remembers the promise made generations earlier. While the rest of the people are preparing to leave Egypt (and according to the Midrash, looting the Egyptians’ riches), Moses sets out to keep the vow made to Joseph:

“And Moses took with him the bones of Joseph, who had exacted an oath from the children of Israel, saying, “God will be sure to take notice of you: then you shall carry up my bones from here with you.”” (Shemot 13:19)

Many interpretations and legends have been attached to this simple verse. The gist of most of them is that after so many years, Moses does not know where to find Joseph’s bones. He receives advice from Serach the daughter of Asher who is the only surviving member of that early generation. She tells him to go to the Nile, where a coffin with Joseph’s bones was sunk years earlier. In one midrash this is done to make the Nile stay fertile, in another, to keep the Israelites in Egypt: if they can’t find Joseph, they cannot go. Moses goes to the edge of the Nile and calls out to Joseph:

“Moses went and stood on the bank of the Nile. He said to Joseph: Joseph, Joseph, the time has arrived about which the Holy One, Blessed be He, took an oath saying that I, i.e., God, will redeem you. And the time for fulfillment of the oath that you administered to the Jewish people that they will bury you in Eretz Yisrael has arrived. If you show yourself, it is good, but if not, we are clear from your oath. Immediately, the casket of Joseph floated to the top of the water.” (Sotah 13a)

The Nile

See page for author, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The casket with Joseph’s bones accompanied the Children of Israel throughout their years in the desert. Some sources say that it was in Joseph’s merit that the Red Sea split and the Jordan stood still. When they enter the land, the final act recorded in the book of Joshua is a series of burials, including Joseph’s, in the city of Shechem that his father purchased and bequeathed to him and his sons:

“The bones of Joseph, which the Israelites had brought up from Egypt, were buried at Shechem, in the piece of ground which Jacob had bought for a hundred kesitahs from the children of Hamor, Shechem’s father, and which had become a heritage of the Josephites.” (Joshua 24:32)

The tel of Shechem

TrickyH, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Burying Joseph’s bones is a symbolic closing of the circle, both on a personal and a national level. He was sold by his brothers near Shechem and he is returned to Shechem. On another level, bringing Joseph’s bones into Israel is the fulfillment of God’s promise that He would return us to our land after many years of exile.

But where is Joseph’s Tomb? Since at least the Byzantine period (fourth century CE) travelers have talked about a site in Balata, the area of Shechem nearest the ancient town (not Neopolis, which is the “new town” of Shechem, built by the Romans). The modern site of Joseph’s tomb is just that – modern, a building from the 19th century. But the area of the burial seems to be correct. The Madaba map, found on a mosaic floor from a Byzantine church in Jordan, clearly indicates Joseph’s tomb on the outskirts of Neopolis and near ancient Shechem. Samaritans built a synagogue next door to the tomb, calling it Helkat HaSadeh, the portion of the field, referencing the land that Jacob bought from Hamor. Jewish travelers like Eshtori haParchi (13th century) and Rabbi Moses Bassula (16th century) also mention the tomb.

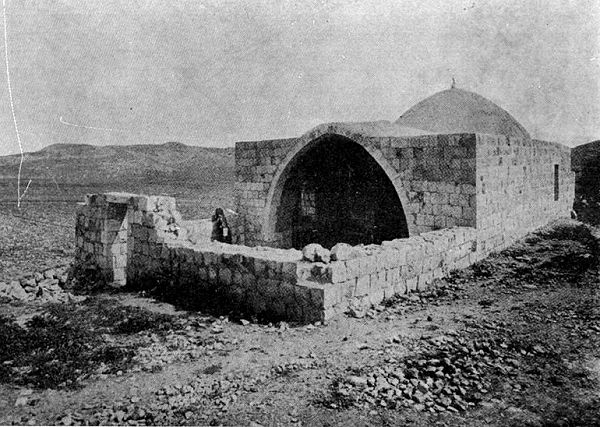

A 19th century picture of the tomb

http://www.syt.co.il/showKever.asp?id=325, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Just as Joseph was a controversial and divisive figure in his lifetime, his tomb has proved likewise after death. In Byzantine times Christians and Samaritans struggled for control of it, each burning down the other’s shrines when they could. In the 19th century it was the Jews who fought with the Samaritans. And in the twentieth century, the struggle has moved to the Muslim Palestinians and the Jewish Israelis.

With Israel’s return to Shechem after the Six-Day War, the site has remained controversial. Jews established a yeshiva there, Muslims attacked soldiers and burnt the structure of the tomb. The horrific culmination was in Oct 2000 when Israeli border police were attacked and a Druse soldier, Madhat Yusuf, was mortally wounded. His evacuation took too long and he died at the site. A few days later, Rabbi Hillel Lieberman from Elon Moreh walked to the tomb and was brutally murdered by Arabs. Since then the army has closed the site and only allows monthly visits at midnight.

Like the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron, Joseph’s Tomb is a site that is revered by all three monotheistic religions. Perhaps one day it can be a place of unity and not of divisiveness.

The tomb today

עדירל, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons