Disaster strikes. A couple is separated. The woman makes her way home from a foreign country alone. But when she appears before the court to testify that her husband is dead and requests permission to remarry, she can only produce one witness to her claim. And one witness is not enough say the rabbis, therefore she remains an aguna, forever chained to her (perhaps dead) husband. But there is one rabbi who allows her to be set free based on one witness’ testimony. That is Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava, whose opinion is quoted here on daf 115 of Yevamot:

“I heard that the Sages do not allow a woman to marry in Eretz Yisrael based on the testimony of one witness, apart from Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava,” (Yevamot 115a)

On the very last page of Yevamot, we get the complete story. Rabbi Akiva returns to tell Rabban Gamliel that there is a support for Rabbi Yehuda’s lone opinion – Rabban Gamliel’s grandfather! Rabban Gamliel the grandson is pleased:

“And when I came and presented the matter before Rabban Gamliel of Yavne, the grandson of Rabban Gamliel the Elder, he rejoiced at my words and said: We have found a companion who agrees with Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava” (Yevamot 122a)

Now that Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava is no longer a lone opinion, the halacha can follow him and a woman can be freed based on the testimony of one witness. But who is Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava and what can we learn from his life story?

Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava was a member of the third generation of Tannaim, a contemporary of Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Yishmael. He was part of the scholars of Yavneh, in central Israel, the place where the Sanhedrin relocated to after the destruction of the Temple. His teacher was the great sage Shmuel HaKatan and he was known as a righteous man. In fact, the Gemara in Bava Kama states:

“anywhere that we say: There was an incident involving a certain pious man חסיד, the pious man is either Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava or Rabbi Yehuda, son of Rabbi Elai,” (Bava Kama 103b)

If this was all we knew about Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava – that he had an illustrious teacher and illustrious colleagues and that he was a pious man – that would not set him apart among the sages. But Rabbi Yehuda’s time made him into someone extraordinary. In a powerful and disturbing passage about martyrdom in the minor tractate Semachot we hear of Rabbi Yehuda’s reaction to the terrible news that Rabbi Akiva has been executed:

“When R. ‘Aḳiva was executed in Caesarea and the news reached R. Yehuda ben Bava and R. Ḥanina ben Teradion, they arose, girded themselves in sackcloth, rent their garments and exclaimed, ‘Our brethren, hearken unto us! R. ‘Aḳiva was not executed for robbery or because he did not labor in the Torah with all his strength. He has only been put to death as a sign. . . Within a short while there will be no place found in the land of Israel where no [slain] will be cast forth” (Semachot chapter 8)

The Roman amphitheater in Caesarea

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Rabbi Yehuda and his companion Rabbi Hanina ben Teradion understand the significance of the moment. Ultimately, they too will be swallowed by the Roman monsters. The time is the period of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, one of the most difficult times in Jewish history. The Roman empire is set on destroying Judaism. They outlaw Torah study, forbid basic practices like circumcision and Shabbat and go after Rabbinic leadership.

Rabbi Yehuda understands that the attack on the rabbis is the worst of all the decrees for without teachers there is no Jewish future. When the Romans outlaw semicha, the traditional ordination of new rabbis, Rabbi Yehuda decides he must take action. He does so in a way that guarantees that Judaism will have leaders but that he himself will die. The story is told in the tractate of Sanhedrin:

“What did Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava do? He went and sat between two large mountains, between two large cities, and between two Shabbat boundaries: Between Usha and Shefaram and there he ordained five elders. And they were: Rabbi Meir, and Rabbi Yehuda, and Rabbi Shimon, and Rabbi Yosei, and Rabbi Elazar ben Shammua. Rav Avya adds that Rabbi Neḥemya was also When their enemies discovered them, Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava said to the newly ordained Sages: My sons, run for your lives. They said to him: My teacher, what will be with you?. He said to them: In any case, I am cast before them like a stone that cannot be overturned; The Roman soldiers did not move from there until they had inserted three hundred iron spears into him, making him appear like a sieve pierced with many holes.” (Sanhedrin 14a)

According to this tale, Rabbi Yehuda deliberately choose to ordain the rabbis in “no man’s land,” between two towns (both of which become homes of the Sanhedrin, making them highly symbolic locations). This way no town could be collectively punished for his act of resistance. He guarantees the next generation of scholars, and in fact these men become the mainstays of Torah in the following years. But he also sacrifices himself so that they may escape. The Ben Yehoyada in his commentary equates the numerical equivalence of the word stone אבן, (when he says, I will be like a stone), with the word from love מאהבה, meaning that Rabbi Yehuda sacrificed himself with a whole heart, with love for Torah and the Jewish people.

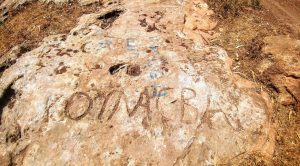

Stone showing the edge of the Shabbat boundary in Usha

שועל, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Although Rabbi Yehuda did not merit a proper eulogy because of the terrible times he lived and died in (Sotah 48b), he is mentioned in two different kinot (mourning poems). Both Arzei HaLevanon, read on Tisha B’Av and Eleh Ezkerah, read on Yom Kippur, mention Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava among the rabbis killed by the Romans. These kinot tell the tale of what are called the Ten Martyrs. They conflate the deaths of the rabbis of this period – Rabbi Akiva, Rabbi Yishmael, Rabbi Hanina and others – into one terrible incident. While historically inaccurate, the kinot capture the flavor of this awful time of persecution.

Traditional site of Rabbi Yehuda’s grave in Shfaram

Michael Yaakovson, Wikipedia

And does any of this tragic story connect to our chained women? Perhaps. There is little straightforward history in the Gemara. The trauma of the Bar Kokhba Revolt is compressed into a few pages of stories in the tractate of Gittin. But the echoes of this horrific time are in the halachot. Just as we heard a few weeks ago about the babies born in hideout caves, here we see a reflection of a time of war and uncertainty. Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava is sadly aware of the tragedies unfolding on his doorstep. In the light of this reality, maybe he wants to make the lives of the women left behind a little easier, by allowing them to remarry.

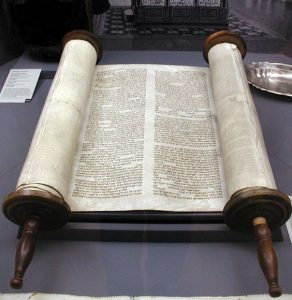

Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava’s actions carry on the chain of tradition. His courage allowed the Torah to continue to be passed down through the generations. In the words of Rabbi Hanina ben Teradyon, as he was burned by the Romans while wrapped in a Torah scroll: the parchment is burning but the letters fly up in the air. Our learning also helps to keep those letters aloft.

HOWI – Horsch, Willy, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons