Was there ever such a thing as a leprous house? Our Gemara asks this question in the context of a debate over whether a rebellious son was ever really executed or an idolatrous city destroyed. Like in the other two instances, here too we have an eyewitness account that a house was destroyed because of leprosy:

“Rabbi Eliezer, son of Rabbi Tzadok says: There was a place in the area of Gaza, and it was called the leprous ruin;” (Sanhedrin 71a)

The fact that Rabbi Eliezer’s example is in Gaza is fascinating because a house can only be defined as a leprous house if it is within the Land of Israel (Mishneh Torah, Laws of Leprosy 14:11). Therefore Gaza is defined here as within the borders of Israel, a fact that is often misconstrued or ignored. Gaza has been in the news and in our minds constantly since October 7th. What is its Jewish history?

Gaza, on the southwestern coast of Israel, was dominated in Biblical times by the Philistines and was never fully conquered by Israel or Judah. When the Babylonians exiled the Jews in the sixth century BCE, they conquered and exiled the Philistines as well, ending their national existence. Gaza was ruled by the Greeks and then conquered by the Hasmonean kings in the first century BCE.

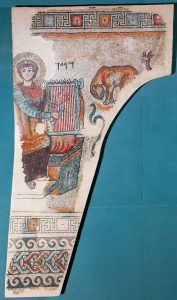

In Byzantine times, although Gaza was not a main center of Jewish life, it did have a thriving Jewish community. We have amazing mosaics from a Byzantine period synagogue in Gaza, showing King David with his harp, charming all sorts of animals. This synagogue even has an inscription, telling us when the mosaic was made and who paid for it:

“We Menachem and Yeshua sons of Yishai the late are lumber merchants, as a sign of admiration for the holiest site, have donated this mosaic in the month of Laos in the year 569.”

Israel Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Jewish life in Gaza was periodic – Jews would settle and prosper, doing business in Gaza’s port and markets. Then an enemy would come along and expel them. This happened with the Romans and the Crusaders. But the Jews would always find a way to return. When the Crusaders were vanquished by the Mamelukes in the 13th century, Jews returned to Gaza and it became one of the most important Jewish communities in late medieval times, on a par with Tzfat and Jerusalem. Here is a memory from the prominent Italian rabbi Rabbi Ovadia of Bartenura, about a visit to Gaza:

“On the Shabbat all the elders and the Torah scholars came to dine with us, bringing cakes and grapes as their custom, and we drank seven or eight cups before eating, and were happy.” (Rabbi Ovadia of Bartenura 1488)

Perhaps the most famous Jewish personality to emerge from medieval Gaza was Rabbi Israel Najara. The Najaras, a prominent rabbinic family, moved from Tzfat to Damascus and ultimately to Gaza. Rabbi Israel became the chief rabbi and was a prominent poet, composing liturgical poems that we still sing today. The most famous one is the Shabbat song “Yah Ribon Olam.”

In modern times, Jews again settled in Gaza but they fled during the 1929 Arab riots. On the night after Yom Kippur 1946, eleven new communities went up overnight in the Negev; one of them was Kfar Darom in the Gaza Strip. Kfar Darom did not survive the Arab attacks in the War of Independence and the entire Strip was conquered by Egypt and emptied of Jews. It was used as a base for terror attacks between 1948-1967.

After the Six-Day War, the Gaza Strip was again part of Israel. Labor Minister Yigal Allon suggested building communities there for security reasons. In 1970 Kfar Darom was reestablished and became part of the bloc of communities know as Gush Katif. Of the twenty-two Jewish communities, most were located in the southern portion of the strip with three in the northern part and one (Netzarim) in the center. When the Jewish communities in the Sinai were dismantled as part of the peace treaty with Egypt in he 1980s. some of the Sinai residents joined the communities of Gush Katif.

A map of the Gaza Strip, Gush Katif settlements are in blue

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Gush Katif was known for its incredible agriculture, particularly the technology of growing vegetables in a way that kept them bug-free. The greenhouses of Gush Katif accounted for 15% of Israeli agricultural exports. The communities, both religious and secular, thrived, but beginning in the 1980s with the First Intifada there were many security challenges. Rockets, road attacks, bus bombings and more created many terrible tragedies. The toll was also felt on the Israeli army who had to protect the communities and the roads. There were strong disagreements over the future of the Gush Katif communities: were they a barrier to even worse attacks in the south of Israel? Or were they the root of the problem? And of course, what would be the fate of over eight thousand residents if the decision was made to withdraw?

Daniel Ventura, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Matters came to a head in 2005. Prime Minister Ariel Sharon pushed through a unilateral decision to evacuate the communities of Gush Katif, despite opposition from the Likud. The residents, as well as many supporters, rallied for months to stop the decree and many acted as though it would not happen, refusing to pack or make contingency plans. When the army finally came in on August 15 2005, there was enormous sadness but thank God little violence. Still, the scenes of soldiers opposite residents, Torah scrolls being carried away and later, Arab attacks on the synagogues left behind were unbearable to watch.

Wherever one stood on the political spectrum, the evacuation from Gush Katif was tragic. Watching people lose their homes, seeing Jewish soldiers have to remove Jews from houses and synagogues, and feeling the deep pain of losing land in Israel affected the whole country. Compounding the pain was the mismanagement by the government of the crisis, with people left without permanent housing solutions or jobs for months and sometimes years. One of the amazing private initiatives, started in the first days of the disengagement, was an organization called Taasukatif. Started by Rabbi Yosef Zvi Rimon in Alon Shvut, its goal was to provide jobs and job training for anyone who needed it.

The former residents of Gush Katif faced a long and difficult journey of rehabilitation. Thankfully, most have found homes and jobs, in the Lachish region, Nitzan, the Golan or on the border with Egypt in Holot Halutzah. The pioneer spirit amazingly still resonates with them and they continue to build the land. Today our thoughts on Gush Katif and a Jewish future in Gaza are inevitably colored by the events of the last year and half. What will be the next incarnation for Gaza?

udi Steinwell Pikiwiki Israel, CC BY 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons