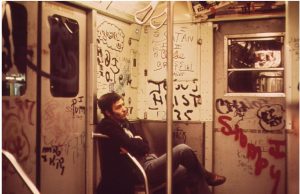

As a child of the seventies from New York, I have a hard time with so called street art. When I was growing up it was called graffiti, it was illegal, a sign of urban decay and it mostly took the form of “Tony loves Gina.” Today, people pay good money to go on graffiti tours and see the art and social protest behind the words and pictures (full disclosure: I have been as well, in Tel Aviv and I will admit it is interesting). But graffiti is a much older art form than the twentieth century and that fact is alluded to in our daf.

Calonius, Erik, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The reality of writing a menu and a guest list is a familiar one to anyone who has Shabbat guests. But writing it on a wall, and not on the back of an envelope? Less familiar (I hope!). But in the ancient world, writing on walls was very common and that is what we will explore today. . A recent book about it quotes a graffito from Pompeii attesting to its ubiquity: “I’m amazed, O wall, that you have not fallen in ruins, you who support the tediousness of so many writers.” ( http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/Reading-the-Writing-on-Pompeiis-Walls.html#ixzz2MYY2yWN6 )

The word graffiti means scribbling and is usually translated as informal writing or drawing in places not usually meant for writing or drawing. The word is modern, perhaps implying that ancient peoples did not think this was an unusual phenomenon, requiring a special word. Graffiti has been found in ancient Egypt, Israel, Greece, Italy and pretty much everywhere. Often it was from travelers or pilgrims who wanted to leave their mark on a site. Seeing it hundreds, sometimes thousands of years later is a thrill, although seeing the same sort of thing from last week would be upsetting. As Michael Press writes in his excellent article (https://hyperallergic.com/484163/the-clandestine-cultural-knowledge-of-ancient-graffiti/), “At what point in time, then, does the vandal move from prosecution to preservation?”

Graffiti is a way of making sure you are remembered. The earliest forms of the alphabet were found in primitive graffiti inscriptions by slaves on a temple in Serabit al Khadem in Sinai, asking the goddess Hathor to remember them in the next world. There is graffiti on mortuary temples in Egypt and in the Dura Europos synagogue in Syria. Perhaps we could even suggest that the Israelites, putting blood on their doorposts, are using a form of graffiti so that God will see them and pass over them?

One of the few places in the ancient world where the walls and everything on them survived completely intact is Pompeii in Italy. The volcanic eruption that buried Pompeii in the year 79 CE preserved the city and all its contents, including those people unlucky enough to not escape in time. As such, Pompeii is a rare “time capsule.” One of the things discovered in Pompeii is that people of all classes wrote all over the walls. The graffiti range from those unprintable in a family blog to juicy bits of gossip, love poetry and public service announcements. They provide a fascinating window into the everyday life of the ancient world.

Political caricature from Pompeii,

Vincent Ramos Wikipedia Commons

There is now a project to map out all the ancient graffiti from Pompeii, on a site called http://ancientgraffiti.org/Graffiti/ Among the insults, obscenities and advertisements, I found a shopping list, just what our daf is talking about!

Nuts, drinks(?) – 14 (coins)

Pork rinds – 3

Three (Loaves of) bread – 51

Three cutlets – 12

Four thyme-flavored sausages – 8

Jews also made graffiti. In a recent book, Professor Karen Stern looks at graffiti written by ancient Jews, in cemeteries, holy places and public spaces and uses it to draw conclusions about everyday life to supplement what we know from written sources. One graffiti drawing that is well known is that of the menorah in Jerusalem, a picture drawn in the first century CE, undoubtedly by someone who saw the original menorah.

Bukvoed, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

One place that seems almost sacrilegious to contemplate graffiti is the Kotel. Today it is common to leave written notes in the Kotel but one hundred years ago people actually wrote on the wall! We see the evidence in this old photograph from the American Colony photographic collection:

Matson (G. Eric and Edith) Photograph collection at the Library of Congress.

So what do we learn from all this? Maybe you should write your Shabbat menu on the wall, just so that archaeologists can find it centuries from now?