“Rather, Rava said: I and the lion of the group explained it. And who is this? It is Rabbi Zeira,” (Bava Batra 88a)

Shakespeare was known for his creative names and insults but he had nothing on the rabbis of the Talmud. Terms of endearment (and many zingers) appear throughout Rabbinic texts and sometimes they are hard to understand. Here Rava calls Rabbi Zeira by a special name: the lion of the group אֲרִי שֶׁבַּחֲבוּרָה. What is this chavurah and why is Rabbi Zeira singled out with a special title?

A lion with his havurah

Charles J. Sharp, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

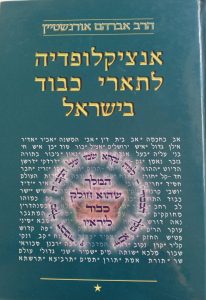

To answer this question I turned to my new favorite book, The Encyclopedia for Honorifics in Israel האנציקלופדיה לתארי כבוד בישראל by Rabbi Avraham Nisan Orenstein (1912-1970). Up until a few weeks ago I did not know that this book existed and I discovered it by chance. It is a four-volume work explaining every name and title in rabbinic literature, from Abba to Tirshata. Some are titles of important people, like the aforementioned lion or tall tree אילן גבוה, some are listings of all the places where “that grandfather,” ההוא סבא is mentioned. Most are positive; some like Aher אחר, the stranger, are negative. This fantastic work, compiled years before computer databases, was written by Rav Orenstein, a survivor who lost most of his family in the Holocaust. He came to Israel as an illegal immigrant in 1948, was banished to Cyprus by the British and eventually he and his wife were allowed into the country. He worked as a teacher, a community rabbi in Tel Aviv and in various government positions for the Poalei Mizrachi and the Religious Zionist parties. In his spare time, he wrote this monumental work as well as several other compositions.

Shulie Mishkin

So what does Rav Orenstein have to say about our lion? First he points out that the phrase has two parts: the lion ארי, and the havurah חבורה. Each one is used individually but the combination is only used for two individuals, Rabbi Zeira and Rabbi Hiyya bar Avin. In both cases, the man designating them with this title is Rava.

“Rather, Rava said: I and the lion of the group explained this. And who is the lion of the group? It is Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Avin.” (Shabbat 111b)

(See also Kiddushin 48b and Sanhedrin 8b for other examples)

The metaphor of lions appears in many places in Tanakh and in Rabbinic literature. As the king of the beasts, lions can symbolize great leaders, scholars and even God. Usually the reference is to a human being as in this famous statement contrasting the mighty lion to the lowly fox:

“Rabbi Mathia ben Harash said: . . And be a tail unto lions, and not a head unto foxes.” (Pirkei Avot 4:15)

Scholars who merit the title lion are among the truly great, both in terms of their learning and what we would call their presence or charisma. Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus, Rabbi Judah the Prince and Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai are among these individuals. Interestingly, the Gemara talks about lions the son of lions and lions the sons of foxes, i.e., what is your ancestry and how does that affect your greatness (see here)

The havura is a more slippery term. It seems to refer to the rabbis of the Land of Israel specifically but some people think it may be about only a certain yeshiva in northern Israel, that of Rabbi Yannai.

Akhbara, where Rabbi Yannai lived

Alaa.hleihel, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

In any case, according to Rav Orenstein, the havura seems to have taken place in a situation where scholars met and determined halachot in a special synod. It may have happened surreptitiously because of Roman persecution. There are a number of examples of this type of halachic decision making in a havurah:

“Rabbi Yannai said: In the group, they counted and concluded that betrothal does not take effect with a yevama.” (Yevamot 92b)

אָמַר רַבִּי יַנַּאי: בַּחֲבוּרָה נִמְנוּ וְגָמְרוּ

“Rabbi Yannai says that when the Sages sat in a group, their opinions were counted and they concluded:” (Makkot 21b)

In other places a havurah seems to just be a gathering of Sages.

“Rabbi Avin is the one who went, and he said: The entire group sided with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan” (Kiddushin 44a)

רַבִּי אָבִין הוּא דְּעָיֵיל וַאֲמַר: חַבְרוּתָא כּוּלַּהּ כְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן.

In the language of the Geonim, hundreds of years later, we hear about the havurah kedosha, a yeshiva in Jerusalem. We mention this havurah ourselves in the Aramaic prayer of yeum purkan recited on Shabbat:

“To the scholars and teacher the holy group in the Land of Israel and in Babylonia”

לְמָרָנָן וְרַבָּנָן חֲבוּרָתָא קַדִּישָׁתָא דִּי בְּאַרְעָא דְיִשרָאֵל וְדִּי בְּבָבֶל

So what does the combination of lion and havurah mean and why is it applied specifically to Rabbi Zeira and to Rabbi Hiyya bar Avin? The two shared some interesting personal details. They were contemporaries, members of the third generation of Amoraim. They were both from Babylonia but traveled to the Land of Israel and studied with the scholars there. And they were both very careful about always finding out from the source whether a certain halacha was actually said by the rabbi in whose name it is cited, or this is just an inference made by the messenger. Rav Orenstein gives many examples of this need for clarification, here is one:

“Rabbi Zeira said to Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi: Did you hear it explicitly or did you hear it by inference?” (Gittin 39b)

Rabbi Hiyya bar Avin goes so far as to quote testimonies of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korha about events that happened long before his time:

“Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Avin said that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korḥa said: An old man reported to me: One time I went to Shiloh, and I smelled the smell of the incense from between its walls.” (Yoma 39b)

The Gemara in Berachot brings a story where the two lions meet each other and discuss the origins of a particular halacha:

“Rabbi Zeira was riding a donkey while Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Avin was coming and walking after him. He said to him: Is it true that you said in the name of Rabbi Yoḥanan that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer” (Berachot 33b)

The two are particularly concerned about the traditions of the Land of Israel and that is where Rav Orenstein connects the havurah to the lion. If the havurah are specifically Eretz Yisrael scholars, then it makes sense that these two, who worry about the transmission of Torat Eretz Yisrael, should be its lions. In fact, Rabbi Zeira expresses the wish to be able to make aliya expressly to learn Torah from the masters there:

“Rabbi Zeira said: [May it be God’s will that] I merit to ascend to Eretz Yisrael, and that I learn this halakha from the mouth of its Master, [Rabbi Elazar]” (Nidah 48a)

Rabbi Zeira, Rabbi Hiyya bar Abin and Rav Orenstein all merited to have their Torah become part of the Torah of the Land of Israel.

Illegal immigration ship arriving in Israel 1947

Unknown source, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons