“Rabbi Yosei ben Kisma said to them: If it is as I say, the water of the Cave of Pamias will be transformed into blood.” (Sanhedrin 98a)

Throughout Jewish history there have been people who have tried to calculate when the Messiah will come. The final chapter of Sanhedrin is replete with speculations, hints and ideas about Messianic times and attempts to find signs of the Messiah’s arrival. Rabbi Yossi ben Kisma ties the Messiah’s appearance to a specific place, the cave of Pamias. Where is this place and how can we understand Rabbi Yossi’s insight?

Pamias is what today we call the Banias or Hermon Stream national park, at the edge of the northern border, where the Upper Galilee ends and the Golan begins.

The Mishnah and Gemara have a number of references to Pamias, which also goes by the name Panias, Caesarion, Caesarea Phillipi, and since the Muslim conquest of the seventh century, Banias (Arabic does not have a letter “P” so “P”s become “B”s). It is one of sourcewaters of the Jordan River:

“The Jordan issues forth from the cave of Pamias, and travels in the Sea of Sivkhi, [the Hula Lake], and in the Sea of Tiberias, [the Sea of Galilee]” (Bava Batra 74b)

Because of their proximity and similarities between them, the rabbis and many later writers like the great Eshtori HaParchi in the 13th century equated the springs of Panias with those of Dan/Leshem/Laish:

“Rabbi Yitzḥak said: Leshem [the city conquered by the tribe of Dan] this is Pamias” (Megillah 6a)

While Dan and Panias both have springs that are sourcewaters for the Jordan and were both sites of idol worship, they are not identical. Dan flourished in Canaanite and Biblical times and faded from prominence just as Panias started to become prominent.

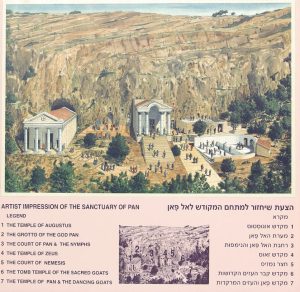

Panias, like other sites with abundant water became a place of pagan worship. As its name implies, it was most closely associated with the Greek god Pan. From its early days in the second century BCE, Panias had temples dedicated to Pan worship. The cave where the waters of the spring emerged was consecrated as a holy place and there was also an area for sacred goat worship as well as other miscellaneous temples.

Pan’s image is antithetical to Jewish ideas of holiness. He was a god of nature, found in grottoes and caves. He had an insatiable appetite for sexual conquest and tales about him include his chasing after and raping women, men and animals. He was clearly a popular god in the Land of Israel. In an excavation at the city of Sussita on the eastern shore of the Kinneret, this realistic mask of Pan was found:

Michael Eisenberg מיכאל איזנברג, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The Mishnah (Parah 8:11) troubles to inform us that the waters of Panias are considered “living waters,” good for purification. Professor Zeev Safrai suggests that Panias is mentioned, unlike other springs, because we might have thought that the rampant idol worship would sully the waters, but this is not true.

In later years, Herod, his son Philip and the Jewish leader Agrippas II all added to the city and to the temples there. The city became known as Caesarea and to differentiate it from its coastal twin, it was called Caesarea Phillippi after Philip.

A reconstruction of the Pan temples

Berthold Werner, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By the time of the Great Revolt, Panias was a firmly Roman city. Josephus relates that the Roman general Titus brought Jewish prisoners there and forced them to participate in gladiator games. The rabbis also mention Panias as a site of Roman rule. We have a number of stories where the emperor Diocletian (late third century CE) is residing at Panias and summons the Jews there or raises their taxes:

“Diocletian oppressed the people of Panias; they told him: we are leaving.” (Yerushalmi Shviit 9:2)

Jews lived at Panias alongside the Romans. Besides Rabbi Yossi ben Kisma, we also hear about Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanos visiting his colleague Rabbi Yochanan at his home in Panias:

“The Sages taught: There was an incident involving Rabbi Eliezer, who stayed in the Upper Galilee in the sukka of Yoḥanan, son of Rabbi Elai, in Caesarea; and some say in Caesarion [another name for Panias].” (Sukkah 27b)

This place of pagans and Jews also held significance for early Christians. The Gospels tell a story of Jesus and his disciples in Panias. The main disciple Peter, affirms that Jesus is the Messiah and Jesus announces that Peter is the rock (a play on words: the Greek word for rock is petra) upon which the church will be built (Matthew 16).

When the Roman empire became Christian in the fourth century CE, so did Panias. The great temple of Pan had a large church built over it. This church was destroyed in various earthquakes and was only recently rediscovered. The excavator, Adi Ehrlich of Haifa University, suggests that it was built less for worship and more to erase the pagan connection of the place.

Panias remained important through Muslim and Crusader times, largely because of its critical water source. Documents in the Cairo Genizah inform us that while the world powers were fighting over it, there were two Jewish communities in Panias (now called Banias), one following Land of Israel traditions and one following Babylonian.

Panias was important for its position, its water and its theology. But why should it be the place to look for signs of the Messiah? I can only offer conjectures since I did not find any answers. One possibility is the unapologetically pagan nature of the site of Panias. The Messiah will redeem the world and perhaps he needs to come from a place of the deepest impurity, an idea that is suggested in other places in our chapter:

“Rabbi Nehorai says: During the generation in which the son of David comes, youths will humiliate elders and elders will stand in deference before youths, and a daughter will rebel against her mother, and a bride against her mother-in-law, and the face of the generation will be like the face of a dog,” (Sanhedrin 97a)

Adi Ehrlich, the excavator of the church, suggests that Rabbi Yossi ben Kisma was familiar with a practice mentioned by Eusebius in his fourth century composition, the Onomasticon. He says that worshippers would throw sacrifices into the sourcewaters of the Banias. This would cause the waters to turn red with blood, a phenomenon that made Rabbi Yossi think this was an eschatological sign.

Finally, perhaps the connection is to the Christian story. In the place where Peter accepts that Jesus is the Messiah, the Jews needed to uproot that false conception and prove that the true Messiah has yet to emerge.

Eschatology and theology aside, the Banias is one of the most beautiful places in Israel. With the reopening of the north, we hope and pray for continued peace and opportunities to visit!

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons