Have you ever been distracted by the art in a synagogue – stained glass windows, decorations on or behind the ark or even on the walls? Synagogues today have a variety of images, some only have flowers and geometric shapes, others have animals like in the representations of the tribes: Judah as a lion and Benjamin as a wolf. Some might even have human figures.

In people’s homes the variety is even greater. Art on the wall may include celestial bodies, portraits and even images of kings and queens. What is the Torah’s position on representative art? As we enter the third chapter of Avoda Zara, we begin to discuss this question.

Reading the Torah text, it seems fairly simple what is allowed and what is forbidden. The second commandment states:

“You shall not make for yourself a sculptured image, or any likeness of what is in the heavens above, or on the earth below, or in the waters under the earth.” (Shmot 20:3)

Rashi explains that this means a picture of anything at all:

וכל תמונה OR ANY LIKENESS i. e. the likeness of any thing אשר בשמים THAT IS IN THE HEAVENS.

It would seem that this prohibition could be mitigated by a number of things: the image has to be a פסל, i.e., three dimensional (but the Torah also says תמונה image), and it cannot be worshipped (see the verses before – have no other gods – and after – don’t bow to these images). However, taken at face value these verses would seem to prohibit any kind of representational art.

Some of the rabbis in the Mishna and later however take a different approach. They set parameters: the image has to have a symbol of power attached to it:

“And the Rabbis say: The only type of statue that is forbidden is any statue that has in its hand a staff, or a bird, or an orb,” (Mishnah Avodah Zarah 3:1)

It has to be encountered in a place and with an attitude of reverence:

“Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel says: Those figures that are upon respectable vessels are forbidden. Those that are upon disgraceful vessels are permitted.”(Mishnah Avodah Zarah 3:2)

We even have a story about Rabban Gamliel who permitted going to a bathhouse with a statue of Aphrodite because in this context, he was not worshipping the statue in any way:

“He said to him: I did not come into its domain; it came into my domain; people do not say: Let us make a bathhouse as an adornment for Aphrodite; rather, they say: Let us make a statue of Aphrodite as an adornment for the bathhouse.” (Mishnah Avodah Zarah 3:3)

The Gemara engages further with this idea and Rav Sheshet issues a blanket permission for everything except human faces, the sun and moon and “dragons” (probably snakes):

“all constellations are permitted, except for the following celestial objects: The sun and the moon. And figures of all faces are permitted, except for the human face. And all figures of other items are permitted except for the figure of a dragon.” (Avodah Zarah 42b)

The Tosefta backs up this idea:

“Rabbi Elazar ben Zadok said all faces were in Jerusalem excepting only a human face.” (Tosefta Avoda Zara 5:2)

So which is it: no images, some images, it depends on the context, it depends on the intention? In true Jewish fashion the answer is yes to all of the above. The more we unearth archaeological artifacts from ancient times, the more we understand the variety of opinions onimagery.

In Second Temple times human and animal images were almost unknown among Jews. Their homes were decorated with geometric or floral patterns, never with animals and people. And when Herod suggests putting an eagle on the gates of the Temple, he provokes a riot:

“Now when these men were informed that the king was wearing away with melancholy, and with a distemper, they dropped words to their acquaintance how it was now a very proper time to defend the cause of God, and to pull down what had been erected contrary to the laws of their country; for it was unlawful there should be any such thing in the temple as images, or faces, or the like representation of any animal whatsoever. Now the king had put up a golden eagle over the great gate of the temple, which these learned men exhorted them to cut down;” (Josephus The Jewish War Book 1 chapter 33)

Herod himself was very circumspect about imagery, even in his own palaces. The one exception we have found so far are the beautiful paintings he had commissioned for the theater at Herodion. Here we find animals and other representative art.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Fast forward a few centuries and travel north a bit and you will find a different story. Synagogues in the Galilee were replete with imagery. Not only classic designs like a menorah and scenes from the Temple:

Bet Shean synagogue

Davidbena, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

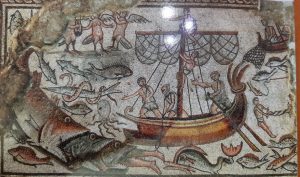

We also find stories from Tanakh like the Tower of Babel, Samson and the foxes and Jonah, as in this mosaic from Hukok, near the Kinneret:

אלון פלצור, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

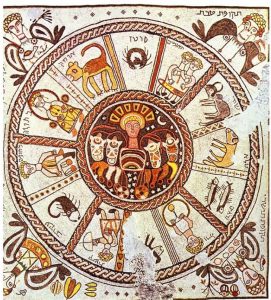

We even find what we would think of as pagan imagery: the zodiac and Helios the sun god in his chariot:

Bet Alfa synagogue

Levan Ramishvili from Tbilisi, Georgia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

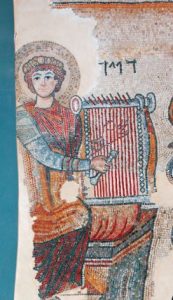

In a sixth century CE a synagogue in Gaza there is a whole menagerie of animals and a picture of King David, looking suspiciously like a Christian saint with a halo around his head:

Israel Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Why are some eras more accepting of images and some less? For one thing, we do not know what the rabbis thought of the synagogue mosaics. There is no proof that these pictures were put before a rabbinic committee to be approved. Perhaps the rabbis avoided these synagogues and these pictures.

However, we can also think about context. In an era replete with paganism, like Second Temple times, Jews avoided even a hint of idolatry. Perhaps in later years, where the threat was not pagan gods but a human god, Jesus, they had less trouble with outmoded images like Helios or the zodiac but avoided human figures. In addition, some places were more “religious” than others. In the south: Sussia, Ein Gedi and others, we find fewer images. Just as the rabbis were trying to understand the parameters of the second commandment, so were the congregants and the artists employed by them.

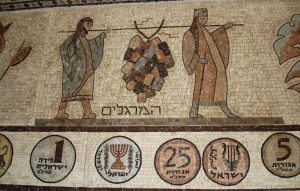

Today, Orthodox synagogues tend to avoid human figures but a fascinating twist was employed in the gorgeous, over-stimulating Tunisian synagogue in Akko. There the walls, floors, ceilings and hallways are covered in modern mosaics. Flora, fauna, coins, animals, maps, verses – you name it, Zion Badash the creator of this iconic building commissioned it. There are many human figures among the mosaics and some have faces:

FLLL, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

However, particularly in the portrayals in the women’s section, there are people who have no facial features. Was this Badash’s way of adhering to the rule of no human figures?

The debate on representational art will undoubtedly go on, not only in synagogues but in all the other media available in our world today, from newspapers to museums to the Internet.