Initially, whoever had a father would have his father teach him Torah, and whoever did not have a father would not learn Torah . . . they instituted an ordinance that teachers of children should be established in Jerusalem.” (Bava Batra 14a)

Twenty-first-century Jerusalem is a city teeming with educational institutions. From multiple styles of kindergartens and elementary schools up to multiple institutions of higher education, both secular and Judaic. The Hebrew University is consistently rated one of the top research schools in the world and Torah learning, from Orthodox to non-denominational is second to none.

But let’s journey back to Jerusalem of two hundred years ago. This small hamlet ruled (and largely neglected) by the Ottoman Empire, had a tiny Jewish community with barely any services. No hospitals, not even any doctors or nurses, no vocational training, and in fact no formal schools at all. Similar to our passage above, whoever had a (rich) father, his father would hire a melamed, a tutor. Others would learn basic reading and writing and then head off to work to bring in money to feed the family.

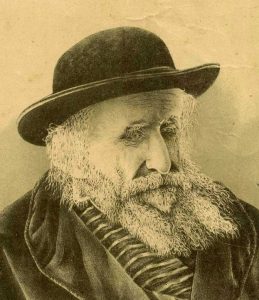

Who was the Yehoshua ben Gamla of nineteenth-century Jerusalem? An unassuming giant of a man named Rabbi Shmuel Salant. He lived in Jerusalem for almost seventy of his ninety-three years and oversaw its transformation from a primitive village to a thriving metropolis. Part of that process was instituting universal (male) education.

Salant was born in 1816 in a small village near Bialystok. He quickly outgrew the local education and went to larger towns to study Torah, eventually ending up in the Pumbedita of Eastern Europe, the Volozhin Yeshiva. He married and took his father-in-law’s last name, Salant. His in-laws moved to Jerusalem and Rav Shmuel and his wife soon followed, in 1840. The long journey to Jerusalem included a stop in the Ottoman city of Constantinople, where Rav Shmuel met and started a lifelong friendship with one of the most important Jewish figures of the day, Sir Moses Montefiore. Montefiore’s financial backing would help Salant in his many projects to improve Jerusalem.

Rabbi Shmuel Salant

By Lithographic print by Moznon c. 1903 – winners-auctions.com, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=90951386

The Jerusalem that the Salants arrived in 1841 was small, poor, and filthy. The Jewish population, split between Ashkenazim and Sephardim, numbered only five thousand people, all living within the cramped confines of the Old City. Whole families lived in one-room apartments, and disease was rampant. Most of the Ashkenazi Jews eked out a bare living, largely supplemented by charity from foreign donations. There were no hospitals and no doctors except those run by Christian missionary societies.

Rav Salant knew that many things had to be changed in this Jerusalem. He went on fundraising trips back to Europe and worked with his ally, Sir Moses Montefiore, to improve conditions for Jerusalem’s Jews. Although barely twenty-five years old, he became the unofficial, and eventually the official chief rabbi of the Ashkenazi community. He outlived his deputies, superiors, and successors. By the time he passed away in 1909. Jerusalem’s Jewish population had skyrocketed from five thousand to thirty thousand, and there were Jewish neighborhoods outside the walls, Jewish hospitals, vocational schools, and perhaps most importantly, cooperation between the Ashkenazim and the Sephardim. Rav Salant was a voice of moderation in a zealous landscape, working to find the middle ground and the way forward toward a unified and powerful Jewish community.

Although Rav Salant brought in much money for the Jews of Jerusalem, he himself refused to relocate from his one-room apartment near the Hurva Synagogue. This is where residents would come to ask their halachic questions. Rav Salant was famous not only for his sagacity but also for his common sense. When a question came before him about whether a pot of meat had become treif when milk fell into it, he was able to permit the meat by discreetly asking the milkman how much he watered down the milk, and thereby knowing how little actual milk fell into the pot.

One of the first projects Rav Salant was involved in was the Etz Hayim yeshiva. The goal was not only universal education for all boys but also a better form of education. Just as our daf discusses educational philosophies, Etz Hayim also wanted to innovate and create a better school. Instead of one tutor taking on a mixed bag of children, of different ages and abilities, the classes at Etz Hayim were grouped by skill level. This way the slowest were not frustrated by not understanding and the fastest could advance. The school also was designed to teach everyone from the smallest boys to married students on the highest level.

Early 20th-century photograph of teachers at the Etz Chaim Yeshiva located in the Hurva Synagogue complex.

By Unknown author – Die Sheinkeit fun Yerushalayim, (Yiddish), by Menachem Mendel Meshi-Zahav, 1986., Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2592656

Etz Hayim began in a small courtyard in the middle of the Jewish Quarter, right near Rav Salant’s very modest home. However, it outgrew these tight quarters and by 1908 it had moved to a much larger building on Jaffa Road, adjacent to the growing Mahane Yehuda market. The market itself was part of the expansion – the yeshiva rented out some of the space in its structures to bring in income. Over the years, some of the greatest teachers of Jerusalem, among them Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer, Rabbi Aryeh Levine and Rabbi Aharon Kotler taught in Etz Hayim. Today the historic building has been slated for preservation, within a larger commercial project. The school has moved, one branch going to the Lemel school building close by in ZIkhron Moshe, and other branches in Givat Shaul and in Betar Illit.

Rav Salant’s legacy of universal education laid the foundation for the education system of today. After overseeing the opening of yet another new neighborhood, Shaarei Hesed, Rav Salant passed away in the summer of 1909. The pillar used for his gravestone came from the courtyard of the Hurva Synagogue, a fitting monument for a man who gave everything to build his beloved city.