During these hot summer days, we all seek out shade when we are outside. But have you ever thought that you cannot stand under that tree because it might be used for idol worship? The prophet Hoshea connects the idea of an Asherah, a sacred tree, with the pleasant shade it provides:

They sacrifice on the mountaintops

And offer on the hills,

Under oaks, poplars, and terebinths

Whose shade is so pleasant.” (Hoshea 4:13)

But what is an Asherah? The Mishnah seems to go in two different directions: the tree itself that is worshipped, or an idol placed under the tree that then renders the tree idolatrous as well:

“MISHNA: Which is an Asherah? Any tree that has idol worship beneath it. Rabbi Shimon says: Any tree that people worship.” (Avodah Zarah 48a)

The Torah seems to support both explanations. We have a few examples, particularly in the book of Devarim, that refer to the Asherah as a tree, albeit one next to an altar, but also one that is planted in order to be worshipped by itself:

“You shall not plant an Asherah, any tree beside the altar of your God that you may make” (Devarim 16:21)

In the book of Shemot the Asherah is a tree that is independent of an altar:

“No, you must tear down their altars, smash their pillars, and cut down their Asherot”(Shemot 34:13)

However, in the books of the Prophets, an Asherah seems to be closer to an idol. The image of Asherah is made during the reign of the idolatrous king of Judah Menashe, and he even placed it in the Temple:

“The sculptured image of Asherah that he made he placed in the House concerning which God had said to David and to his son Solomon, “In this House and in Jerusalem, which I chose out of all the tribes of Israel, I will establish My name forever.” (Kings II 21:7)

Later the righteous king Josiah has this Asherah destroyed:

“He brought out the Asherah from the House of God to the Kidron Valley outside Jerusalem, and burned it in the Kidron Valley; he beat it to dust and scattered its dust over the burial ground of the common people.” (Kings II 23:6)

Often Asherah is paired with that other major Canaanite god, Baal:

“Now summon all Israel to join me at Mount Carmel, together with the four hundred and fifty prophets of Baal and the four hundred prophets of Asherah, who eat at Jezebel’s table.” (Kings I 18:19)

Is the Asherah a tree, an idol or both?

The phenomenon of sacred trees is well-known in our region. A tree has the good fortune to grow large and old and not be cut down. People see its size and are amazed, they then attribute some holiness to it and worship it (or near it). This keeps it from being cut down and it becomes even older, and thus even holier. The cycle can continue for centuries. We have example of trees like this today, like the famous “Lone Tree” in Gush Etzion:

Dr. Avishai Teicher Pikiwiki Israel, CC BY 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons

The Tosefta is familiar with these sacred trees as well and mentions three specific ones as Asherot:

“Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar says, There are three Asherahs in Eretz Yisrael: a carob in Kfar Patam, and [a carob] in Kfar Pigshah, [and] a sycamore in Rani and in Karmel.” (Tosefta Avodah Zarah 7:4)

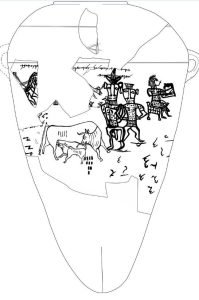

What about the Asherah that is an idol? Asherah was the consort of the supreme Canaanite god El, and the mother of Baal, that is why they are often portrayed together. Some Israelites may have even seen Asherah as the “wife” not of El but of God. In a remote outpost in the Sinai desert, a drawing and inscription were found that stated:

“For YHVH and His Asherah” (Inscription from Kuntillat Ajrud in the Sinai, 9th century BCE)

Drawing found at Kuntilat Ajrud

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The idea that God has a wife is clearly opposed to monotheistic ideas and we can understand why such an idea would be anathema to the prophets.

Do we have other images of the Asherah? One of the most common idols found all over Israelite sites from Biblical times are something called Judean Pillar Figurines. They are exaggerated female figures:

Chamberi, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

They were found throughout Judah, from Arad and Beersheva in the south to Gibeon and Bet El in the north. The vast majority (over four hundred!) were found in Jerusalem. They date to the eighth – seventh century BCE. Their appearance: clearly female with large breasts – implies that they were some kind of fertility figure and that is often how they are referred to. But some scholars identify them with Asherah, the most prominent female goddess in Canaan. Others see them as a representation of Ashtoret, a confusingly named but separate female deity (Asherah’s daughter in the Canaanite pantheon).

The most intriguing explanation of these figures is by a scholar named Ryan Byrne. He argues that while these idols look like other goddesses, they acquired a new meaning due to the circumstances of their time and place. They were not necessarily idols but a propaganda campaign carried out by the kingdom of Judah after the Assyrian invasion. While Jerusalem was saved from the Assyrian attack, the rest of Judah was decimated. Towns were destroyed, many people were killed and others were taken captive to Assyria. Judah needed a baby boom and these figures were a way to tell people, get started having babies!

Is there a connection between the two definitions of the Asherah? Some scholars suggest that the pillar bottom in these figurines represents the tree part of the Asherah, while the torso and head represent the female goddess

Were there any Asherot around in the time of the Mishnah? The tree kind seems to have definitely survived. We have the evidence of the Tosefta as well as the sacred trees that we still see today. It seems less likely that the Rabbis saw the idol version of the Asherah and perhaps that is why they focus on the trees. In any case, whether or not they knew the details of Canaanite mythology, the Rabbis understood that an Asherah was threatening to the idea of the one true God.

צילום: אולגה גנזר, CC BY 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons