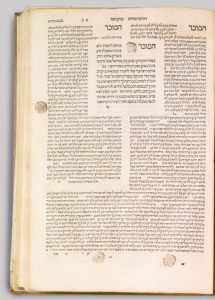

You may have noticed that your daily daf shiur or learning session has been shorter these past few weeks. You may have also noticed that the Gemara you are toting around is heavier than they usually are (unless you use the handy dandy small paperback volumes). You are not imagining this – Bava Batra has some of the shortest pages and the longest page counts in the whole Shas. Part of the reason for that is because of a sad announcement halfway down the Rashi column on page 29a:

“up until here Rashi zt”l explained, from here we have the commentary of Rabbi Shmuel ben Rabbi Meir”

Rashi, as has been often stated, is the student’s best friend (see here). His brilliant and concise explanations of the Gemara elucidate this often impenetrable text. But here Rashi left us and his grandson, the Rashbam, continues his labors. The Rashbam’s commentary is much longer, and with the way our Talmud pages are laid out, this makes each Bava Batra page much shorter to accommodate all that text. Rashbam’s Talmud commentary is often maligned as inferior to Rashi, we will address that later in this post. But first, let’s understand who Rabbi Shmuel ben Meir was.

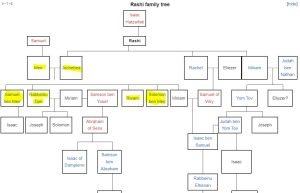

As is well known, Rashi had only daughters, no sons. He married those daughters off to great scholars and they produced Rabbinic dynasties, many of whom became known as the Baalei Tosafot, the authors of the Tosafot. Rabbi Meir, a scholar in Ramerupt (northern France) married Yocheved and they had four sons, each one a Torah giant. Shmuel was the oldest, his brothers were Yaakov, otherwise known as Rabbenu Tam, Yitzchak, AKA the Rivam, and Shlomo, a great grammarian.

Being the oldest grandson, Shmuel had the privilege of studying with his grandfather, as he mentions often in his own works. While we don’t know his exact birth date, we do know that Rashi was born in 1040 and died in 1105. Shmuel had to have been born at least 35 years after Rashi but not too late that he could not have had a significant time to study with him. Scholars suggest that Shmuel was born sometime between 1075 and 1085 and he lived a long life, although we also do not know his death date. He worked the land and also kept sheep, and like Rashi, he familiarized himself with many fields of everyday life.

Northern France, and particularly the area dominated by Rashi and his family, was a pious and scholarly place. Rashbam grew up secure in the knowledge that he was part of an exceptional community and family. Perhaps this is what gave him the courage to interpret Torah and Talmud in more radical ways than his predecessors. He also lived in a very Christian world and anti-Christian polemics sometimes surface in his writings, often in subtle ways.

Historic Jewish area of Troyes

Emmanuel DYAN from Paris, France, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The Rashbam is best known for his commentary on the Torah. It seems he wrote on all the books of Tanakh; however, not all the works survived (at least as far as we know). His guiding principle in his work is the search for what he calls “peshat,” a term that was defined differently by different people. He particularly disagrees with his grandfather about what is meant by this literal or simple meaning of the text, as he famously wrote in his commentary to Bereshit 37. After explaining that the text must be explained according to its literal meaning: אין המקרא יוצא מידי פשוטו , he goes on to say that despite this, most scholars focus on the derash, the exegetical meaning.

“And also our teacher Shlomo, my mother’s father, enlightener of the exile, who explained Torah, Neviim and Ktuvim, wanted to explain the literal version of the text. And I, Shmuel ben Rabbi Meir his son-in law, zt”l argued with him and he admitted to me that if had had the time, he should have made other explanations according to the literary meanings we are innovating daily.” (Rashbam, Bereshit 37:2)

Rashbam’s search for literal meaning included looking at the customs of the time, gaining a deep understanding of the language and structure of the verse and trying to parse the larger methodology of the Torah text. It also meant that he sometimes interpreted a verse not according to its halachic explanation but rather its literal meaning. When the Torah talks about remembering the Exodus, there is the famous verse:

“And this shall serve you as a sign on your hand and as a reminder on your forehead” (Shmot 13:9)

While most commentators, including Rashi, interpret this as the commandment to wear tefillin, Rashbam explains that it is meant metaphorically, rather than teaching us to create a physical object.

Yoavlemmer, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Another famous example is where he shows that in the story of Creation, day comes first and then nighttime. In this way, Shabbat should begin on Saturday morning and not as traditional Judaism explains, that the night precedes the day.

Although these interpretations caused an outcry (particularly by Rashbam’s contemporary, Abraham ibn Ezra) they were in no way meant to topple normative halacha. Rashbam was looking at the text in a critical and literary way while still keeping all the principles of the Rabbinic explanations of the verses.

Unlike Rashbam’s commentary to the Torah, which has been studied, published in critical editions and praised as being modern, his Talmud exegesis has been largely ignored or dismissed. Much of it has been lost; we essentially have only his works on (most of) Bava Batra and on the last chapter of Pesachim, although he is mentioned by the Baalei Tosafot in other places. When people do write about these two works, they inevitably compare him to Rashi and denigrate his wordy style. But perhaps we are looking at him all wrong – rather than complaining that he is NOT Rashi, maybe we should be seeing that he IS Rashbam? In other words, if his Torah commentary was so groundbreaking, wouldn’t his Talmud commentary be similar?

This is the premise of an article written by David Farkas (https://seforimblog.com/2012/11/rashbam-talmudist-reconsidered/?print=print) where he suggests that Rashbam’s writings on Talmud include many of the classic elements of a modern, academic way of looking at the Gemara. This includes understanding that the text developed over time and had an editor. It also had a consistent methodology, as Rashbam says in Pesachim 101b – this is the method of the Gemara.

Rashbam looked, to the best of his abilities, for manuscripts in order to find the most correct texts. He fought against exaggeration and supernatural beliefs, saying that numbers may be inflated (Pesachim 119a). And he sought out outside experts to explain texts, as when he says in Bava Batra 56 that he asked farmers about crop rotation.

All these motifs show us a teacher who wanted to understand the Gemara on a deep level, as a whole text composed over a long time, with editors trying to piece it together, similar to what Talmud scholars do today. Rashbam was ahead of his time, something his grandfather would have admired.

Sotheby’s, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This article includes the insights of my friend and colleague Dr. Avigail Rock zt”l, from her book on Biblical commentators, as well as the ideas in the aforementioned article by Farkas. Thank you!