Remember those scenes in the movies of someone giving away her possessions as she lies at death’s door? That is what halacha calls a שכיב מרע. The gift of such a person has validity even if a formal transfer of ownership has not taken place. Our Gemara brings several possibilities to explain how this law is derived from the Torah. One of them is the fascinating case of Ahithophel, advisor to King David and then to his son Avshalom:

“Rami bar Yeḥezkel says: [The halakha with regard to the gift of a person on his deathbed is derived] from here: ‘And when Ahithophel saw that his counsel was not followed, he saddled his ass, and went to his home, to his city; and he instructed his household, and strangled himself’ ” (II Samuel 17:23) (Bava Batra 147a)

What is the background to this distressing story?

King David’s life, turbulent in his youth, became even more filled with drama and intrigue when he was crowned king. The culmination of many family conflicts comes when his beloved son Avshalom rebels against him. The story is related in the second book of Samuel, chapters 15 – 18. David, threatened by his son, has to flee his capital of Jerusalem, taking with him his trusted advisors. He heads northeast, to the tribal lands of Benjamin. Meanwhile, Avshalom coopts David’s best advisor, Ahithophel the Giloni.

Ahithophel’s hometown of Gilo is mentioned in the book of Joshua, in the same context as towns in the southern Hebron Hills. Scholars once suggested that the Gilo in our tale is a town just south of Jerusalem, its name preserved in the Christian Arab town of Bet Jala and the Jerusalem neighborhood of Gilo. Although Biblical era remains have been found there, today the consensus is that Ahithophel’s Gilo is the one closer to Hebron.

The desertion of Ahithophel to Avshalom’s camp was a major blow to King David. He retaliated by having a different trusted advisor, Hushai the Archite, pretend to defect to Avshalom’s camp while actually remaining loyal to David, thereby acting as a fifth column in the palace. Hushai’s goal was to undermine Ahithophel. who was considered such a brilliant strategist that his advice was compared to that of God:

“In those days, the advice which Ahithophel gave was accepted like an oracle sought from God;” (II Samuel 16:23)

And what was this wise advice? First Ahithophel tells Avshalom to publicly sleep with the king’s concubines who have been left behind to guard the house. This display of disrespect towards his father would reassure people on the fence about supporting Avshalom, who feared that he might reconcile with David. After Avshalom does this, Ahithophel offers his second suggestion: strike while the iron is hot, attack David now while he and his men are exhausted, and then you will unite the people behind you:

“And Ahithophel said to Absalom, Let me pick twelve thousand men and set out tonight in pursuit of David. I will come upon him when he is weary and disheartened, and I will throw him into a panic; and when all the troops with him flee, I will kill the king alone.” (II Samuel 17:1)

This is actually excellent advice. David is exhausted and probably would have been routed quickly. But God listens to David’s prayer (15:31) and plants a seed of doubt in Avshalom’s mind. Perhaps he is concerned that Ahithophel plans to lead the charge himself against David, perhaps he just wants to hear another opinion. He turns to Hushai, who counsels him to wait until he has amassed a larger fighting force and only then attack David. Avshalom accepts Hushai’s advice.

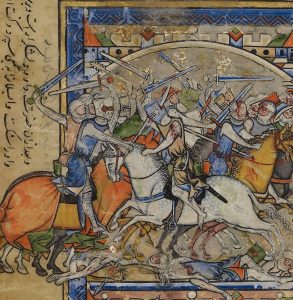

Picture from the Morgan Bible of the battle between David and Avshalom’s armies

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The outcome is twofold: Hushai sends a message to David’s camp, advising them to flee across the Jordan. The time he buys ultimately saves David and gets Avshalom killed. Meanwhile, Ahithophel, understanding the inevitable outcome of Hushai’s plan, goes home to put his house in order. He is well aware that when Avshalom is defeated and David returns, his head will be on the chopping block. He would rather commit suicide than be executed as a traitor. This way, he will be buried respectfully and, (here is the tie in to our Gemara) his possessions will go to his family and not be confiscated by the state, as would normally happen to someone who betrays the king (see the story of Navot’s vineyard, I Kings 21).

The Ahithophel story is fascinating in its description of realpolitik, betrayal and the high stakes of treason. But the rabbis add another layer. In their telling, Ahithophel is not only a brilliant strategist but a Torah scholar and the head of the Sanhedrin. He is David’s teacher as well as his learning partner, and David honors him as such:

“One who learns from his fellow one chapter, or one halakhah, or one verse, or one word, or even one letter, is obligated to treat him with honor; for so we find with David, king of Israel, who learned from Ahitophel no more than two things, yet called him his master, his guide and his beloved friend, as it is said, ‘But it was you, a man mine equal, my guide and my beloved friend’ ” (Psalms 55:14). (Mishnah Avot 6:3)

Yet despite Ahithophel’s wisdom, he is one of a handful of people that the Rabbis decree are barred from the next world:

“Three kings and four commoners have no share in the World-to-Come. . . The four commoners are: Balaam, Doeg; Ahithophel; and Gehazi.” (Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:12)

There is no doubt that Ahithophel was a sinner:: he betrayed a righteous king, advised Avshalom to commit sexual sins and murder and ultimately committed suicide. But does this make him worse than many other villains in the Bible, including Avshalom himself?

While sin may be bad, it is forgivable. What is unforgivable according to the rabbis is someone who knows better, and uses his Torah knowledge in a twisted way. This is the common denominator among the four who will not enter the next world. The message of the Rabbis is that being learned is not enough, one must also observe the commandments:

“Rich in Torah and poor in Torah, they all descend to Gehenna. Rich in Torah, such as Doeg and Ahithophel, because they did not observe the Torah, they descended to Gehenna even though they were heads of the Sanhedrin.” (Midrash Tehillim 49:2)

And have a fear of God:

“Rather, [Doeg and Ahithophel] would not conclude halakhic discussions in accordance with halakhic rulings, as it is written: “The secret of the Lord is with those who fear Him” (Psalms 25:14). [Since they did not fear God, they did not arrive at halakhic conclusions despite their keen intellect.]” (Sanhedrin 106b)

Our Gemara however offers a hint of a better ending. Ahithophel left his family three pieces of advice:

“Do not be participants in a dispute. And do not rebel against the kingship of the house of David. And if the festival of Shavuot is a clear day, sow wheat,” (Bava Batra 147a)

The first two are obvious lessons learned from his own debacle: don’t encourage dissent and do not rebel against the House of David. But what is the meaning of the third piece of advice? Why would the timing of wheat planting be Ahithophel’s last will and testament?

Many commentators give an allegorical meaning to this idea. Some suggest that Ahithophel wants to ensure that people can make a living; this will enable peace in the land. The Lubavitcher Rebbe connects the timing – Shavuot – to accepting the yoke of Heaven at Mount Sinai, something absent from Ahithophel’s life. Another interesting thought connects to a statement of the Gemara in Sanhedrin (101b). There the Rabbis explain that Ahithophel misunderstood a sign from God: he thought he would inherit the kingship and acted accordingly. His idea “sprouted” (ניבט) but he took it in the wrong direction. In his advice to his children he says don’t jump to conclusions, wait for the right moment to plant your seeds. Only then, and with a fear of God, can you succeed.

Wheatfield, Vincent Van Gogh

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons