“additions can be made to the city [of Jerusalem] or to the Temple courtyards only by the king, a prophet, the Urim VeTummim, and the Sanhedrin of seventy-one, and with two thanks-offerings and with song.” (Shevuot 14b)

How does your city grow? In the case of Jerusalem, like many ancient cities, little by little. While our Mishnah describes an official ceremony to consecrate new parts of the city of Jerusalem, we rarely hear about such a ceremony in our sources. One noted exception is the ceremony conducted when Nehemiah and the people finished rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem in the early years of the Return to Zion:

“At the dedication of the wall of Jerusalem, the Levites, wherever they lived, were sought out and brought to Jerusalem to celebrate a joyful dedication with thanksgiving and with song, accompanied by cymbals, harps, and lyres” (Nehemiah 12: 27)

As pointed out by Professor Zeev Safrai, the celebration in Nehemiah is clearly the model for the ceremony in the Mishnah. Significantly, the Kohanim and Leviim in the Bible are replaced in the Mishnah by the teachers and judges of the Sanhedrin, part of the Rabbis’ push to create a new elite, based on learning and not on family alone.

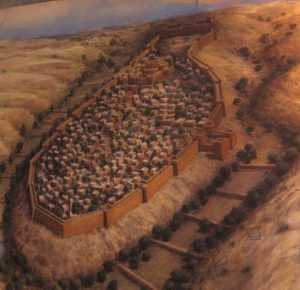

Jerusalem began as a small town about five thousand years ago, on a hill above the Gihon spring. It only came under Israelite control with King David’s conquest and his choice of it as his capital, three thousand years ago. David not only conquered the city, he also began its expansion process:

“David occupied the stronghold and renamed it the City of David; David also fortified the surrounding area, from the Millo inward” (Samuel 2 5:9)

David’s son Solomon added to the city when he built his palace and the Temple on Mount Moriah, north of the existing city:

Daniel Ventura, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

At some point Jerusalem expanded from its position on the eastern ridge to the western hill, the area where the Jewish Quarter is today. When did that happen? Up until 1967, this was one of the major questions in Jerusalem’s archaeology. Minimalists claimed that the city remained small and contained to the east until late in the Second Temple period, maximalists on the other hand said that by late First Temple times Jerusalem included the Western hill. Neither had any proof.

And then, with the return of the Old City to Israeli hands, Nahman Avigad was able to excavate and discover a massive wall in the Jewish Quarter which he dated to King Hezekiah’s times. This proved to all that by the seventh century BCE (and perhaps even earlier), Jerusalem became a city that connected the two hills, עיר שחוברה לה יחדיו.

Red is original city, yellow is expansion in late First Temple times

user:תמרה, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons

The Broad Wall

יעקב, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

After the First Temple and the city were destroyed by the Babylonians, those who returned had to start all over again. The walls of the city had to be rebuilt, as Nehemiah describes after he surveys them:

“Then I said to them, ‘You see the bad state we are in, Jerusalem lying in ruins and its gates destroyed by fire. Come, let us rebuild the wall of Jerusalem and suffer no more disgrace.’ ”(Nehemiah 2:17)

The limited manpower and resources of that early generation meant that the city shrank to an even smaller size than it had been before King David’s conquest. Still, the rebuilding and resettling was a triumphant occasion, one that we see not only in the description of the dedication ceremony quoted earlier but also in a contemporary prophet’s beautiful messianic promises:

“Thus said GOD of Hosts: There shall yet be elderly men and women in the squares of Jerusalem, each with staff in hand because of their great age. And the squares of the city shall be crowded with boys and girls playing in the squares” (Zechariah 8:4-5)

Throughout the Second Temple period, the city continued to expand. Under the Hasmonean dynasty it reached the size it had been during the final days of the First Temple. Herod expanded it yet again in the first century BCE and a final growth happened in the first century CE, under King Agrippa I. These last suburbs were in the north of the city and perhaps they are what our Gemara is referring to when it talks about the two ponds or swamps added to the city, below the Mount of Olives:

“Abba Shaul says: There were two ponds [bitzin] on the Mount of Olives, a lower and an upper. The lower was consecrated with all [the procedures mentioned in the Mishna] the upper was not consecrated with all these procedures, but by those who returned from the exile, without a king and without the Urim VeTummim.” (Shevuot 16a)

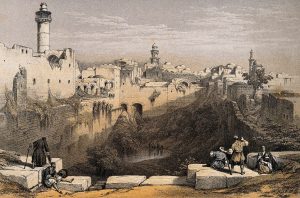

We know that one of the newer areas of the city was called Bezetha and it was in the northeast; it contained an important reservoir (“pond”) and it was enclosed by Agrippa to protect the city:

Haghe, Louis, 1806-1885, lithographer; Roberts, David, 1796-1864, artist, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This area is mentioned by Josephus in his description of the Jerusalem of his time:

“For as the city grew more populous, it gradually crept beyond its old limits: and those parts of it that stood northward of the temple, and joined that hill to the city, made it considerably larger, and occasioned that hill, which is in number the fourth, and is called Bezetha, to be inhabited also. . . Since therefore its inhabitants stood in need of a covering, the father of the present King, and of the same name with him, Agrippa, began that wall we spoke of.” (Josephus The Wars of the Jews Book 5 chapter4)

The Gemara gives the same reason for this expansion:

“Because it was a weak point of Jerusalem and it would have been easy to conquer the city from there,” (Shevuot 16a)

The three walls of Jerusalem (map is oriented east)

Daniel Ventura, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Despite the growth of Jerusalem and its protective walls, it was viciously conquered and destroyed by the Romans during the Great Revolt. After that Jerusalem waxed and waned, expanding in the time of the Byzantines, shrinking again during the endless wars between Muslims and Christians. Only with the growth of the population in the nineteenth century did the city begin to outgrow its former shape and expand beyond even the dreams of Nehemiah. Today while the Old City is still within walls, new Jerusalem has grown by such leaps and bounds that it can be said to have fulfilled a different prophecy:

“Jerusalem shall be peopled as a city without walls, so many shall be the people and cattle it contains” (Zechariah 2:8)

israeltourism, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons