Eruvin 22

שֶׁמַּשְׁכִּים וּמַעֲרִיב עֲלֵיהֶן לְבֵית הַמִּדְרָשׁ. רַבָּה אָמַר: בְּמִי שֶׁמַּשְׁחִיר פָּנָיו עֲלֵיהֶן כְּעוֹרֵב.

who, for the Torah’s sake, gets up early in the morning [shaḥar] and stays late in the evening [erev] in the study hall. Rabba said: In him who, for the Torah’s sake, blackens his face like a raven, i.e., who fasts and deprives himself for the sake of Torah study.

רָבָא אָמַר: בְּמִי שֶׁמֵּשִׂים עַצְמוֹ אַכְזָרִי עַל בָּנָיו וְעַל בְּנֵי בֵּיתוֹ כְּעוֹרֵב. כִּי הָא דְּרַב אַדָּא בַּר מַתְנָא הֲוָה קָאָזֵיל לְבֵי רַב, אֲמַרָה לֵיהּ דְּבֵיתְהוּ: יָנוֹקֵי דִידָךְ מַאי אֶעֱבֵיד לְהוּ? אֲמַר לַהּ: מִי שְׁלִימוּ קוּרָמֵי בְּאַגְמָא?

Rava said: In him who makes himself cruel to his sons and other members of his household like a raven for the sake of Torah. This was the case with Rav Adda bar Mattana, who was about to go to the study hall to learn Torah, and his wife said to him: What shall I do for your children? How shall I feed them in your absence? He said to her: Are all the rushes [kurmei] in the marsh already gone? If there is no other bread, let them eat food prepared from rushes.

״וּמְשַׁלֵּם לְשׂוֹנְאָיו אֶל פָּנָיו לְהַאֲבִידוֹ״, אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: אִילְמָלֵא מִקְרָא כָּתוּב, אִי אֶפְשָׁר לְאוֹמְרוֹ — כִּבְיָכוֹל כְּאָדָם שֶׁנּוֹשֵׂא מַשּׂוֹי עַל פָּנָיו, וּמְבַקֵּשׁ לְהַשְׁלִיכוֹ מִמֶּנּוּ.

The Gemara proceeds to interpret a different verse homiletically: “And He repays them that hate Him to His face to destroy them; He will not be slack to him that hates Him, He will repay him to his face” (Deuteronomy 7:10). Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: Were the verse not written in this manner, it would be impossible to utter it, in deference to God, for it could be understood, as it were, like a person who bears a burden on his face, and wishes to throw it off. Written slightly differently, the verse could have been understood as implying that God is unable, as it were, to bear the situation, but must punish the wicked immediately.

״לֹא יְאַחֵר לְשׂוֹנְאוֹ״, אָמַר רַבִּי אִילָא: לְשׂוֹנְאָיו הוּא דְּלֹא יְאַחֵר, אֲבָל יְאַחֵר לַצַּדִּיקִים גְּמוּרִים.

With regard to the words “He shall not be slack to him that hates Him,” Rabbi Ila said: He will not be slack in bringing punishment to him that hates Him, but He will be slack in rewarding those who are absolutely righteous, as the reward of the righteous does not arrive immediately, but only in the World-to-Come.

וְהַיְינוּ דְּאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: מַאי דִּכְתִיב ״אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי מְצַוְּךָ הַיּוֹם לַעֲשׂוֹתָם״, ״הַיּוֹם לַעֲשׂוֹתָם״ — וְלֹא לְמָחָר לַעֲשׂוֹתָם, ״הַיּוֹם לַעֲשׂוֹתָם״ — לְמָחָר לְקַבֵּל שְׂכָרָם.

And that is what Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: What is the meaning of that which is written: “And you shall keep the commandments, and the statutes, and the judgments which I command you today to do them” (Deuteronomy 7:11)? It means: Today is the time to do them, in this world, and tomorrow is not the time to do them, as there is no obligation or opportunity to fulfill mitzvot in the World-to-Come. Furthermore, it means: Today is the time to do them, but only tomorrow, in the ultimate future, is the time to receive reward for doing them.

אָמַר רַבִּי חַגַּי, וְאִיתֵּימָא רַבִּי שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר נַחְמָנִי: מַאי דִּכְתִיב ״אֶרֶךְ אַפַּיִם״? ״אֶרֶךְ אַף״ מִבְּעֵי לֵיהּ!

In a similar vein, Rabbi Ḥaggai said, and some say it was Rabbi Shmuel bar Naḥmani: What is the meaning of that which is written: “And the Lord passed by before him, and proclaimed: The Lord, the Lord, merciful and gracious, long-suffering [erekh appayim], and abundant in love and truth” (Exodus 34:6)? Why does it say “erekh appayim,” using a plural form? It should have said erekh af, using the singular form.

אֶלָּא אֶרֶךְ אַפַּיִם לְצַדִּיקִים, אֶרֶךְ אַפַּיִם לָרְשָׁעִים.

What this means is that God is long-suffering in two ways: He is long-suffering toward the righteous, i.e., He delays payment of their reward; and He is also long-suffering toward the wicked, i.e., He does not punish them immediately.

רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר עַד בֵּית סָאתַיִם וְכוּ׳. אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: בּוֹר וּפַסִּין קָאָמַר, אוֹ דִילְמָא בּוֹר וְלֹא פַּסִּין קָאָמַר?

The mishna stated that Rabbi Yehuda says: The area may be expanded up to an area of two beit se’a, an area of five thousand square cubits. A dilemma was raised before the Sages in clarification of this statement: Did he speak of the area of the cistern itself and that enclosed by the upright boards, that the total area enclosed by the upright boards may be expanded up to, but may not exceed, an area of two beit se’a? Or perhaps he spoke of the area of the cistern without that enclosed by the upright boards, that the cistern itself may be expanded up to an area of two beit se’a? In that case, the total area enclosed by the boards could exceed an area of two beit se’a.

אָדָם נוֹתֵן עֵינָיו בְּבוֹרוֹ, וְלָא גָּזְרִינַן דִּילְמָא אָתֵי לְטַלְטוֹלֵי יוֹתֵר מִבֵּית סָאתַיִם בְּקַרְפֵּף;

The underlying rationale of each side of this dilemma is as follows: Does one fix his eyes on his cistern, keeping in mind that the partition is made because of it, and therefore, since the area of the cistern is not greater than an area of two beit se’a, we do not decree lest he come to carry also in an enclosure [karpef], an enclosed storage space behind the house that was not originally surrounded by a fence for the purpose of residence, even when it is more than an area of two beit se’a?

אוֹ דִילְמָא, אָדָם נוֹתֵן עֵינָיו בִּמְחִיצָתוֹ, וְגָזְרִינַן דִּילְמָא אָתֵי לְאִיחַלּוֹפֵי יוֹתֵר מִבֵּית סָאתַיִם בְּקַרְפֵּף.

Or perhaps a person fixes his eyes on his partition, and does not pay attention to the cistern, but only to the area enclosed by the partition. And in this case we do decree, lest he come to confuse this case with that of a karpef that is larger than an area of two beit se’a, and come to carry there, because of the similarity between them.

תָּא שְׁמַע: כַּמָּה הֵן מְקוֹרָבִין — כְּדֵי רֹאשָׁהּ וְרוּבָּהּ שֶׁל פָּרָה, וְכַמָּה הֵן מְרוּחָקִין — אֲפִילּוּ כּוֹר אֲפִילּוּ כּוֹרַיִים. רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: בֵּית סָאתַיִם — מוּתָּר, יָתֵר מִבֵּית סָאתַיִם — אָסוּר.

In order to resolve this question, the Gemara cites a proof: Come and hear what was taught in a baraita: How close may the boards be to the well? They may be as close as the length of the head and most of the body of a cow. And how far may they be from the well? The enclosed area may be expanded even to the area of a beit kor and even two beit kor, provided that one adds more upright boards or increases their size so as to reduce the size of the gaps between them. Rabbi Yehuda says: Up to an area of two beit se’a, it is permitted to enclose the area in this manner; more than an area of two beit se’a, it is prohibited.

אָמְרוּ לְרַבִּי יְהוּדָה: אִי אַתָּה מוֹדֶה בְּדִיר וְסַהַר מוּקְצֶה וְחָצֵר, אֲפִילּוּ בֵּית חֲמֵשֶׁת כּוֹרִים וּבֵית עֲשֶׂרֶת כּוֹרִים, שֶׁמּוּתָּר.

The other Rabbis said to Rabbi Yehuda: Do you not concede with regard to a pen, a stable, a backyard, and a courtyard, that even one the size of five beit kor and even of ten beit kor is permitted for use?

אָמַר לָהֶם: זוֹ מְחִיצָה, וְאֵלּוּ פַּסִּין.

Rabbi Yehuda said to them: A distinction can be made between the cases, for this, the wall surrounding the pen, the stable or the yard, is a proper partition, and hence it is permitted to carry in them even if they are more than an area of two beit se’a. However, these are only upright boards, and they only allow one to carry if the area they enclose is not more than an area of two beit se’a.

רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן אֶלְעָזָר אוֹמֵר: בּוֹר בֵּית סָאתַיִם אַבֵּית סָאתַיִם — מוּתָּר, וְלֹא אָמְרוּ לְהַרְחִיק אֶלָּא כְּדֵי רֹאשָׁהּ וְרוּבָּהּ שֶׁל פָּרָה.

Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar says: A cistern the length of two beit se’a by the width of two beit se’a is permitted, and they only said to distance the upright boards from the cistern as much as the length of the head and most of the body of a cow.

הָא מִדְּקָאָמַר רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן אֶלְעָזָר בּוֹר וְלֹא פַּסִּין, מִכְּלָל דְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה בּוֹר וּפַסִּין קָאָמַר. וְלָא הִיא, רַבִּי יְהוּדָה בּוֹר בְּלֹא פַּסִּין קָאָמַר.

The Gemara tries to draw an inference from this baraita: From the fact that Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar spoke only of the cistern itself and not of the upright boards, we can infer that Rabbi Yehuda spoke of both the cistern itself and the area enclosed by the upright boards. The Gemara rejects this argument: It is not so. When Rabbi Yehuda said that the area may be expanded up to an area of two beit se’a, he was, in fact, speaking of the area of the cistern without that which is enclosed by the upright boards.

אִי הָכִי, הַיְינוּ דְּרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן אֶלְעָזָר! אִיכָּא בֵּינַיְיהוּ אֲרִיךְ וְקַטִּין.

The Gemara asks: If so, that is exactly what Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar said. The Gemara answers: There is a practical halakhic difference between them in a case where the enclosed area is long and narrow. Rabbi Yehuda permits using it, whereas Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar requires that the area be square.

כְּלָל אָמַר רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן אֶלְעָזָר: כׇּל אֲוִיר שֶׁתַּשְׁמִישׁוֹ לְדִירָה, כְּגוֹן דִּיר וְסַהַר מוּקְצֶה וְחָצֵר, אֲפִילּוּ בֵּית חֲמֵשֶׁת כּוֹרִים וּבֵית עֲשֶׂרֶת כּוֹרִים — מוּתָּר.

The Gemara adds: Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar stated a principle: With regard to any enclosed space that is used as a dwelling, such as a pen, a stable, a backyard, or a courtyard, even if it lacks a roof and even if the structure has the area of five beit kor and even ten beit kor, it is permitted to carry in it.

וְכׇל דִּירָה שֶׁתַּשְׁמִישָׁהּ לַאֲוִיר, כְּגוֹן בּוּרְגָּנִין שֶׁבַּשָּׂדוֹת, בֵּית סָאתַיִם — מוּתָּר, יֶתֶר מִבֵּית סָאתַיִם — אָסוּר.

And with regard to any dwelling that is used for the space outside it, i.e., whose partitions were arranged not so that it could be lived in, but for the sake of the field or yard outside, such as field huts, if its area was two beit se’a, it is permitted to carry in it; but if its area was more than two beit se’a, it is prohibited to do so.

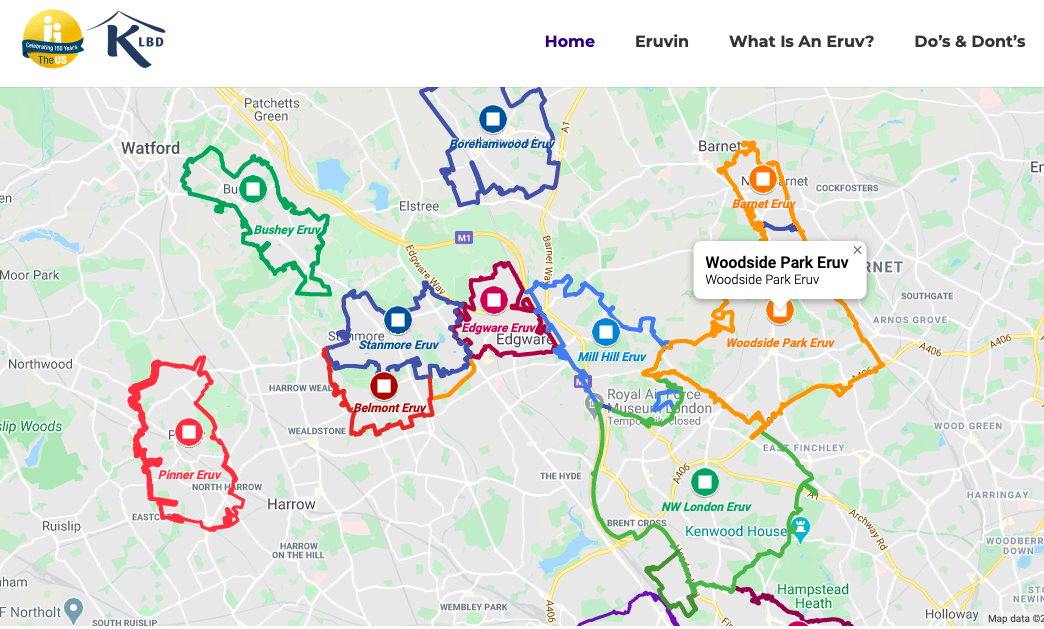

מַתְנִי׳ רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: אִם הָיָה דֶּרֶךְ רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים מַפְסַקְתָּן — יְסַלְּקֶנָּה לִצְדָדִין. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: אֵינוֹ צָרִיךְ.

MISHNA: Rabbi Yehuda says: If the path of the public domain passes through the area of the upright boards surrounding a well and obstructs it, one must divert the path to the sides, so that the public will circumvent the enclosed area; otherwise, the partition is invalid and the enclosed area cannot be regarded as a private domain. And the Rabbis say: One need not divert the path of the public domain, for the partition is valid even if many people pass through it.

גְּמָ׳ רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן וְרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר דְּאָמְרִי תַּרְוַויְיהוּ: כָּאן הוֹדִיעֲךָ כּוֹחָן שֶׁל מְחִיצּוֹת.

GEMARA: Rabbi Yoḥanan and Rabbi Elazar both said: Here, the Rabbis informed you of the strength of partitions; although a path of the public domain passes through the partitions and the partitions do not constitute effective barriers, they are still strong enough to allow one to carry.

כָּאן, וּסְבִירָא לֵיהּ? וְהָאָמַר רַבָּה בַּר בַּר חָנָה אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: יְרוּשָׁלַיִם, אִילְמָלֵא דַּלְתוֹתֶיהָ נִנְעָלוֹת בַּלַּיְלָה, חַיָּיבִין עָלֶיהָ מִשּׁוּם רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים.

The Gemara wishes to clarify the meaning of Rabbi Yoḥanan’s statement: Did he mean here that the Rabbis expressed this idea, and he agrees with them that a public thoroughfare does not invalidate a partition? Didn’t Rabba bar bar Ḥana say that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: With regard to Jerusalem, even though it is walled, were it not for the fact that its doors are locked at night, one would be liable for carrying in it on Shabbat because its thoroughfares are regarded as the public domain? Apparently, Rabbi Yoḥanan maintains that a partition is not strong enough to overcome the passage of many people.

אֶלָּא: כָּאן — וְלָא סְבִירָא לֵיהּ.

Rather, Rabbi Yoḥanan’s statement must be understood as follows: Here, the Rabbis expressed this idea, although he does not agree with them.

וּרְמִי דְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה אַדְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה. וּרְמִי דְּרַבָּנַן אַדְּרַבָּנַן.

The Gemara raised a contradiction between this statement of Rabbi Yehuda and another statement of Rabbi Yehuda, and raised a contradiction between this statement of the Rabbis and another statement of the Rabbis.

דְּתַנְיָא, יָתֵר עַל כֵּן אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: מִי שֶׁהָיוּ לוֹ שְׁנֵי בָתִּים מִשְּׁנֵי צִידֵּי רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים, עוֹשֶׂה לוֹ לֶחִי מִכָּאן וְלֶחִי מִכָּאן, אוֹ קוֹרָה מִכָּאן וְקוֹרָה מִכָּאן, וְנוֹשֵׂא וְנוֹתֵן בָּאֶמְצַע. אָמְרוּ לוֹ: אֵין מְעָרְבִין רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים בְּכָךְ.

The other statements are as it was taught in the Tosefta: Furthermore, Rabbi Yehuda said: If one had two houses on the two sides of the public domain, and he wishes to carry from one house to the other on Shabbat via the public domain, he may place a side post from here, perpendicular to the public domain, and an additional side post from here, on the other side of the public domain, or he may place a cross beam from here, from one end of one house to the end of the house opposite it, and another cross beam from here, from the other side of the house, and carry objects and place them in the area between them because the two added partitions turn the area in the middle into a private domain. The Rabbis said to him: One cannot make the public domain fit for carrying by means of an eiruv in this manner, i.e., by means of a side post alone, when many people continue to walk through the public thoroughfare in the middle.

קַשְׁיָא דְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה אַדְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה, קַשְׁיָא דְּרַבָּנַן אַדְּרַבָּנַן.

Consequently, there is a contradiction between one statement of Rabbi Yehuda and the other statement of Rabbi Yehuda, and there is also a contradiction between one statement of the Rabbis and the other statement of the Rabbis.

דְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה אַדְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה לָא קַשְׁיָא: הָתָם — דְּאִיכָּא שְׁתֵּי מְחִיצּוֹת מְעַלְּיָיתָא. הָכָא — לֵיכָּא שְׁתֵּי מְחִיצּוֹת מְעַלְּיָיתָא,

The Gemara answers: Between one statement of Rabbi Yehuda and the other statement of Rabbi Yehuda there is no contradiction, because one can differentiate between them. There, in the case of the two houses, there are two proper partitions, for the houses are real partitions, and two partitions suffice to establish a separate domain. However, here, in the case of the upright boards, there are not two proper partitions, for the upright boards are not real partitions.

דְּרַבָּנַן אַדְּרַבָּנַן [נָמֵי] לָא קַשְׁיָא: הָכָא — אִיכָּא שֵׁם אַרְבַּע מְחִיצּוֹת, הָתָם — לֵיכָּא שֵׁם אַרְבַּע מְחִיצּוֹת.

Between one statement of the Rabbis and the other statement of the Rabbis there is also no contradiction, as here, with regard to the upright boards, there is a nominal set of four partitions; on all four sides side there are at least two cubits of some form of partition, so the cistern is regarded as enclosed by four partitions. However, there, with regard to the two houses, there is not a nominal set of four partitions.

אָמַר רַבִּי יִצְחָק בַּר יוֹסֵף אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל אֵין חַיָּיבִין עָלֶיהָ מִשּׁוּם רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים. יָתֵיב רַב דִּימִי וְקָאֲמַר לֵיהּ לְהָא שְׁמַעְתָּא. אֲמַר לֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי לְרַב דִּימִי: מַאי טַעְמָא?

Rabbi Yitzḥak bar Yosef said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: In Eretz Yisrael one is not liable for carrying in the public domain. Rav Dimi sat and recited this halakha. Abaye said to Rav Dimi: What is the reason underlying this ruling?

אִילֵּימָא מִשּׁוּם דְּמַקֵּיף לַהּ סוּלְּמָא דְצוֹר מֵהָךְ גִּיסָא וּמַחְתָנָא דְגָדֵר מֵהָךְ גִּיסָא — בָּבֶל נָמֵי, מַקִּיף לֵהּ פְּרָת מֵהָךְ גִּיסָא וְדִיגְלַת מֵהַאי גִּיסָא! דְּכוּלָּא עָלְמָא נָמֵי מַקִּיף אוֹקְיָינוֹס! דִּילְמָא מַעֲלוֹת וּמוֹרָדוֹת קָאָמְרַתְּ?

If you say this law because Eretz Yisrael is surrounded by the Ladder of Tyre on one side and the slope of Gader on the other side, each formation being over ten handbreadths high and constituting a valid partition, then Babylonia, which is also surrounded by the Euphrates River on one side and the Tigris River on the other side, should not be considered a public domain either. Moreover, the entire world is also surrounded by the ocean, and therefore there should be no public domain anywhere in the world. Rather, perhaps you spoke of the ascents and descents of Eretz Yisrael, which are not easy to traverse and hence should not have the status of a public domain?

אֲמַר לֵיהּ: קַרְקַפְנָא, חֲזִיתֵיהּ לְרֵישָׁךְ בֵּי עַמּוּדֵי כִּי אֲמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן לְהָא שְׁמַעְתָּא.

Rav Dimi said to him: Man of great skull, i.e., man of distinction, I saw your head between the pillars of the study hall when Rabbi Yoḥanan taught this halakha, meaning you grasped the meaning as though you actually were present in the study hall and heard the statement from Rabbi Yoḥanan himself.

אִיתְּמַר נָמֵי, כִּי אֲתָא רָבִין אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, וְאָמְרִי לַהּ, אָמַר רַבִּי אֲבָהוּ אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: מַעֲלוֹת וּמוֹרָדוֹת שֶׁבְּאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל אֵין חַיָּיבִין עֲלֵיהֶן מִשּׁוּם רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים לְפִי שֶׁאֵינָן כְּדִגְלֵי מִדְבָּר.

It was also stated that when Ravin came from Eretz Yisrael he said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said, and some say it was Rabbi Abbahu who said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: In the case of the ascents and descents of Eretz Yisrael, one is not liable for carrying in the public domain, because they are not like the banners in the desert. To be regarded as a public domain, a place must be similar to the area in which the banners of the tribes of Israel passed in the desert, i.e., it must be level and suitable for the passage of large numbers of people.

בְּעָא מִינֵּיהּ רַחֲבָה מֵרָבָא: תֵּל הַמִּתְלַקֵּט עֲשָׂרָה מִתּוֹךְ אַרְבַּע, וְרַבִּים בּוֹקְעִין בּוֹ, חַיָּיבִין עָלָיו מִשּׁוּם רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים אוֹ אֵין חַיָּיבִין עָלָיו?

Raḥava raised a dilemma before Rava: In the case of a mound that rises to a height of ten handbreadths within four cubits, thereby fulfilling the conditions that create a private domain, but many people traverse it, is one liable for carrying in the public domain or is one not liable?

אַלִּיבָּא דְרַבָּנַן לָא תִּיבְּעֵי לָךְ: הַשְׁתָּא, וּמָה הָתָם דְּנִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתֵּיהּ — אָמְרִי רַבָּנַן לָא אָתוּ רַבִּים וּמְבַטְּלִי לַהּ מְחִיצְתָּא, הָכָא, דְּלָא נִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתֵּיהּ — לֹא כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן!

The Gemara explains: According to the opinion of the Rabbis, this should not be a dilemma for you. Just as there, with regard to the upright boards surrounding a well, where the use of the public domain is convenient, the Rabbis say that the public does not come and invalidate the partition; here, where its use is inconvenient due to the slope, all the more so should the mound be considered partitioned off as a private domain, and the passage of the public should not invalidate it.

כִּי תִּיבְּעֵי לָךְ אַלִּיבָּא דְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה. מַאי, הָתָם הוּא דְּנִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתֵּיהּ, הָכָא הוּא דְּלָא נִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתֵּיהּ — לָא אָתוּ רַבִּים וּמְבַטְּלִי מְחִיצְתָּא? אוֹ דִילְמָא לָא שְׁנָא? אֲמַר לֵיהּ: חַיָּיבִין.

Where there should be a dilemma for you is according to the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda. What is the halakha? Does he maintain his position only there, because the use of the public domain is convenient, whereas here, where its use is inconvenient, he too would agree that the public does not come and invalidate the partition? Or perhaps there is no difference? Rava said to Raḥava: In such a case, one is liable for carrying in a public domain.

וַאֲפִילּוּ עוֹלִין לוֹ בְּחֶבֶל? אֲמַר לֵיהּ: אִין. וַאֲפִילּוּ בְּמַעֲלוֹת בֵּית מָרוֹן?! אֲמַר לֵיהּ: אִין.

Raḥava asked him: And do you issue this ruling even in the case of a slope that is so steep that in order to climb it one must ascend it by means of a rope? He said to him: Yes. He asked him further: And even in the case of the ascents of Beit Meron, which are exceedingly steep? He said to him: Yes.

אֵיתִיבֵיהּ: חָצֵר שֶׁהָרַבִּים נִכְנָסִין לָהּ בָּזוֹ וְיוֹצְאִין בָּזוֹ — רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים לַטּוּמְאָה, וּרְשׁוּת הַיָּחִיד לַשַּׁבָּת.

Raḥava raised an objection to Rava’s opinion from the Tosefta: A courtyard that was properly surrounded by partitions, into which many people enter on this side and exit on that other side, is treated like the public domain with regard to ritual impurity, so that in cases of doubt, the person is considered ritually pure, as uncertainty concerning ritual impurity only renders a person impure in an area defined as a private domain; however, it is still treated like the private domain with regard to Shabbat.

מַנִּי? אִילֵּימָא רַבָּנַן, הַשְׁתָּא וּמָה הָתָם — דְּנִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתֵּיהּ, אָמְרִי רַבָּנַן: לָא אָתוּ רַבִּים וּמְבַטְּלִי מְחִיצְתָּא, הָכָא — דְּלָא נִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתֵּיהּ, לֹא כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן!

He proceeds to clarify the Tosefta: Who is the author of this statement? If you say it was the Rabbis, there is a difficulty: Just as there, with regard to the upright boards surrounding a well, where the use of the public domain is convenient, the Rabbis say that the public does not come and invalidate the partition; here, in the case of the courtyard, where its use as a path for a public domain is inconvenient, all the more so should they say that the passage of many people does not invalidate the partition and therefore there would be no need to discuss this case.

אֶלָּא לָאו, רַבִּי יְהוּדָה הִיא?

Rather, is it not in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda? This indicates that even Rabbi Yehuda differentiates between different paths in the public domain.

לָא, לְעוֹלָם רַבָּנַן, וּרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים לַטּוּמְאָה אִיצְטְרִיכָא לֵיהּ.

Rava replied: No; actually, you can explain that this Tosefta was taught in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis. As to the question raised with regard to the novelty of this case according to their approach, it was necessary for them to teach us that such a courtyard is treated like the public domain with regard to ritual impurity, even though it is considered a private domain with respect to Shabbat.

תָּא שְׁמַע: מְבוֹאוֹת הַמְפוּלָּשׁוֹת בְּבוֹרוֹת, בְּשִׁיחִין וּבִמְעָרוֹת — רְשׁוּת הַיָּחִיד לְשַׁבָּת וּרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים לַטּוּמְאָה.

Raḥava attempts to cite a proof again, this time from a mishna: Come and hear the following teaching: Alleyways that open in cisterns, ditches or caves constitute the private domain with regard to Shabbat and the public domain with regard to ritual impurity.

״בְּבוֹרוֹת״ סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ? אֶלָּא: לְבוֹרוֹת — רְשׁוּת הַיָּחִיד לְשַׁבָּת וּרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים לַטּוּמְאָה.

The Gemara first clarifies the wording of the mishna: Should it enter your mind to say that the correct reading is in cisterns [baborot]; is it possible to speak of alleyways that open inside cisterns? Rather, it should be corrected as follows: Alleyways that open out into cisterns [laborot] constitute the private domain with regard to Shabbat and the public domain with regard to ritual impurity.

מַנִּי? אִילֵּימָא רַבָּנַן, הַשְׁתָּא וּמָה הָתָם — דְּנִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתֵּיהּ, אָמְרִי: לָא אָתוּ רַבִּים וּמְבַטְּלִי לַהּ, הָכָא — דְּלָא נִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתֵּיהּ, לֹא כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן! אֶלָּא לָאו רַבִּי יְהוּדָה הִיא?

Raḥava proceeds to clarify the matter: Who is the author of this mishna? Now, if you say it is the Rabbis, there is a difficulty: Just as there, with regard to the upright boards surrounding a well, where the use of the public thoroughfare is convenient, the Rabbis say that the public does not come and invalidate the partition; here, in the case of an alleyway, where its use as a public thoroughfare is inconvenient, all the more so should they say that the passage of many people does not invalidate the partition, and so there was no need to discuss this case. Rather, isn’t it in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda?

לָא, לְעוֹלָם רַבָּנַן, וּרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים לַטּוּמְאָה אִיצְטְרִיכָא לֵיהּ.

Rava refutes this argument: No; actually, you can explain that this mishna was taught in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis. It does present a novel teaching, as it was necessary for them to teach us that such an alleyway has the status of the public domain with regard to ritual impurity. Although it is not a convenient place to cross, it is considered a public domain with respect to impurity, since many people are found there.

תָּא שְׁמַע: שְׁבִילֵי בֵּית גִּילְגּוּל וְכַיּוֹצֵא בָּהֶן — רְשׁוּת הַיָּחִיד לַשַּׁבָּת וּרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים לַטּוּמְאָה.

Once again Raḥava attempts to cite a proof from a mishna: Come and hear the following teaching: The paths of Beit Gilgul, which are difficult to traverse, and similar ones have the status of the private domain with regard to Shabbat, and that of the public domain with regard to ritual impurity.

וְאֵיזֶהוּ שְׁבִילֵי בֵּית גִּילְגּוּל? אָמְרִי דְּבֵי רַבִּי יַנַּאי: כֹּל שֶׁאֵין הָעֶבֶד יָכוֹל לִיטּוֹל סְאָה שֶׁל חִיטִּין וְיָרוּץ לִפְנֵי סַרְדְּיוֹט.

The Gemara asks: And what paths are like the paths of Beit Gilgul? The school of Rabbi Yannai say: This is any path in which a slave [eved] is unable to take up a se’a of wheat by hand and run before an officer [sardeyot], despite his fear of him.

מַנִּי? אִילֵּימָא רַבָּנַן, הַשְׁתָּא וּמָה הָתָם — דְּנִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתָּא, אָמְרִי רַבָּנַן: לָא אָתוּ רַבִּים וּמְבַטְּלִי לַהּ מְחִיצְתָּא. הָכָא — דְּלָא נִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתָּא, לֹא כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן! אֶלָּא לָאו, רַבִּי יְהוּדָה הִיא?

Raḥava proceeds to clarify the issue: Who is the author of this mishna? Now, if you say it is the Rabbis, there is a difficulty: Just as there, with regard to the upright boards surrounding a well, where the use of the public thoroughfare is convenient, the Rabbis say that the public does not come and invalidate the partition; here, in the case of the paths of Beit Gilgul, where their use as a public pathway is inconvenient, all the more so should they say that the passage of many people does not invalidate the partitions. Rather, is it not in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda?

אֲמַר לֵיהּ: שְׁבִילֵי בֵּית גִּילְגּוּל קָאָמְרַתְּ? יְהוֹשֻׁעַ אוֹהֵב יִשְׂרָאֵל הָיָה, עָמַד וְתִיקֵּן לָהֶם דְּרָכִים וּסְרַטְיָא, כֹּל הֵיכָא דְּנִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתָּא — מְסָרָהּ לָרַבִּים, כֹּל הֵיכָא דְּלָא נִיחָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתָּא — מְסָרָהּ לַיָּחִיד.

Rava said to him: Did you say the paths of Beit Gilgul? Joshua, who conquered the land and divided it among the tribes, was a lover of Israel. He rose up and established roads and highways for them; any place that was convenient to use he handed over to the public, and any place that was inconvenient to use he handed over to an individual. Therefore, the roads of Eretz Yisrael, which like the paths of Beit Gilgul are not easy to use, have the status of a private domain. However, there is no general rule in other places that roads that are difficult to traverse do not have the status of a public domain.

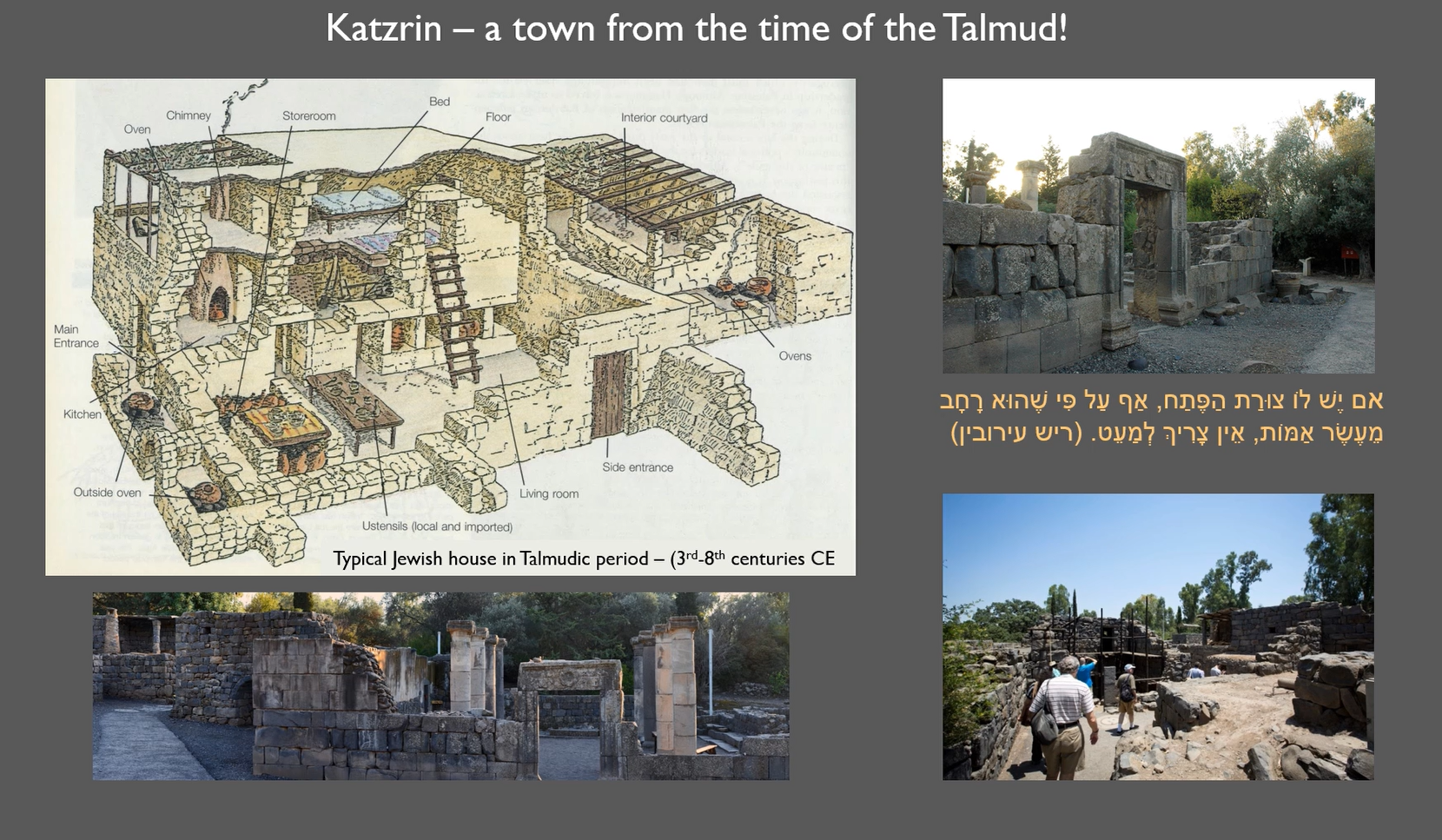

מַתְנִי׳ אֶחָד בּוֹר הָרַבִּים וּבְאֵר הָרַבִּים וּבְאֵר הַיָּחִיד — עוֹשִׂין לָהֶן פַּסִּין.

MISHNA: In the case of a public cistern containing collected water, as well as a public well containing spring water, and even a private well, one may arrange upright boards around them in order to allow one to carry in the enclosed area, as delineated above.

אֲבָל לְבוֹר הַיָּחִיד — עוֹשִׂין לוֹ מְחִיצָה גָּבוֹהַּ עֲשָׂרָה טְפָחִים, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא.

But in the case of a private cistern, there are two deficiencies: It belongs to an individual, and it does not contain spring water. Consequently, it is impossible to permit drawing from it on Shabbat by means of boards set up in the corners; rather, one must construct for it a proper partition ten handbreadths high; this is the statement of Rabbi Akiva.

רַבִּי יְהוּדָה בֶּן בָּבָא אוֹמֵר: אֵין עוֹשִׂין פַּסִּין אֶלָּא לִבְאֵר הָרַבִּים בִּלְבַד, וְלַשְּׁאָר — עוֹשִׂין חֲגוֹרָה גָּבוֹהַּ עֲשָׂרָה טְפָחִים.

Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava says: One may arrange upright boards only for a public well. But for the others, that is, a public cistern or a private well, one must set up a belt, i.e., a partition consisting of ropes, ten handbreadths high. Such an arrangement creates a proper partition based on the principle of lavud, namely, that solid surfaces with gaps between them smaller than three handbreadths are considered joined.