Eruvin 26

שַׁלְפִינְהוּ. אֲזַל רַב פָּפָּא וְרַב הוּנָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב יְהוֹשֻׁעַ, נַקְטִינְהוּ מִבָּתְרֵיהּ.

and removed the reeds, as he maintained that they were unnecessary; he regarded the entire orchard as having been enclosed for the purpose of residence, owing to the banqueting pavilion. Rav Pappa and Rav Huna, son of Rav Yehoshua, went after him and collected the reeds, so as to prevent Rav Huna bar Ḥinnana from restoring the partitions, as they were Rava’s students and wanted to enforce his ruling.

לִמְחַר אֵיתִיבֵיהּ רָבִינָא לְרָבָא: עִיר חֲדָשָׁה מוֹדְדִין לָהּ מִיְּשִׁיבָתָהּ, וִישָׁנָה מֵחוֹמָתָהּ.

On the following day, on Shabbat, Ravina raised an objection to Rava’s opinion from a baraita which states: In the case of a new town, we measure the Shabbat limit from its settled area, from where it is actually inhabited; and in the case of an old town, we measure the Shabbat limit from its wall, even if it is not inhabited up to its wall.

אֵיזוֹ הִיא חֲדָשָׁה וְאֵיזוֹ הִיא יְשָׁנָה? חֲדָשָׁה, שֶׁהוּקְּפָה וּלְבַסּוֹף יָשְׁבָה. יְשָׁנָה, יָשְׁבָה וּלְבַסּוֹף הוּקְּפָה. וְהַאי נָמֵי כְּהוּקְּפָה וּלְבַסּוֹף יָשְׁבָה דָּמֵי!

What is a new town, and what is an old town? A new town is one that was first surrounded by a wall, and only afterward settled, meaning that the town’s residents arrived after the wall had already been erected; an old town is one that was first settled, and only afterward surrounded by a wall. Ravina raised his objection: And this orchard should also be considered like a town that was first surrounded by a wall and only afterward settled, as it had not been enclosed from the outset for the purpose of residence. Even if a dwelling was later erected there, this should not turn it into a place that had been enclosed for the purpose of residence.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב פָּפָּא לְרָבָא: וְהָאָמַר רַב אַסִּי מְחִיצוֹת אַדְרְכָלִין לָא שְׁמָהּ מְחִיצָה, אַלְמָא כֵּיוָן דְּלִצְנִיעוּתָא עֲבִידָא לַהּ — לָא הָוְיָא מְחִיצָה. הָכָא נָמֵי, כֵּיוָן דְּלִצְנִיעוּתָא עֲבִידָא — לָא הָוְיָא מְחִיצָה.

Seeing that an additional objection could be raised against his teacher’s position, Rav Pappa said to Rava: Didn’t Rav Asi say that the temporary screens erected by architects to serve as protection against the sun and the like are not deemed valid partitions? Apparently, since it was erected only for privacy, and not for the purpose of permanent dwelling, it is not considered a valid partition. Here too, then, with regard to the fence around the orchard, since it was erected only for privacy, it should not be considered a valid partition.

וְאָמַר רַב הוּנָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב יְהוֹשֻׁעַ לְרָבָא: וְהָאָמַר רַב הוּנָא: מְחִיצָה הָעֲשׂוּיָה לְנַחַת — לֹא שְׁמָהּ מְחִיצָה!

And Rav Huna, son of Rav Yehoshua, said to Rava: Didn’t Rav Huna say that a partition made for resting objects alongside it and thereby providing them with protection is not considered a valid partition?

דְּהָא רַבָּה בַּר אֲבוּהּ מְעָרֵב לַהּ לְכוּלַּהּ מָחוֹזָא עַרְסְיָיתָא עַרְסְיָיתָא מִשּׁוּם פֵּירָא דְּבֵי תוֹרֵי. וְהָא פֵּירָא דְּבֵי תוֹרֵי כִּמְחִיצָה הָעֲשׂוּיָה לְנַחַת דָּמְיָא.

This is as Rabba bar Avuh did, when he constructed an eiruv separately for each row of houses in the whole town of Meḥoza, due to the ditches from which the cattle would feed that separated the rows of houses from one another. Shouldn’t such cattle ditches be considered like a partition made for resting objects alongside it? Such a partition is invalid. All these proofs indicate that Rava was wrong to remove the reed fences erected by Rav Huna bar Ḥinnana, for those fences were indeed necessary.

קָרֵי עֲלַיְיהוּ רֵישׁ גָּלוּתָא: ״חֲכָמִים הֵמָּה לְהָרַע וּלְהֵיטִיב לֹא יָדָעוּ״.

With regard to the resolution of this incident, the Exilarch recited the following verse about these Rabbis: “They are wise to do evil, but to do good they have no knowledge” (Jeremiah 4:22), as on Friday they ruined the arrangement that Rav Huna bar Ḥinnana had made to permit carrying from the house to the pavilion, and the next day all they could do was prove that they had acted improperly the day before and that it was prohibited to carry in the orchard.

אָמַר רַבִּי אִלְעַאי, שָׁמַעְתִּי מֵרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר: וַאֲפִילּוּ בֵּית כּוֹר. מַתְנִיתִין דְּלָא כַּחֲנַנְיָה. דְּתַנְיָא, חֲנַנְיָה אוֹמֵר: וַאֲפִילּוּ הִיא אַרְבָּעִים סְאָה כְּאִסְטְרַטְיָא שֶׁל מֶלֶךְ.

We learned in the mishna: Rabbi Elai said: I heard from Rabbi Eliezer that one is permitted to carry in a garden or karpef, even if the garden is the size of a beit kor, thirty times larger than a beit se’a. The Gemara notes that all agree that what the mishna taught was not in accordance with the opinion of Ḥananya, as it was taught in a baraita that Ḥananya says: One is permitted to carry even if it is the size of forty beit se’a, like the court of a king.

אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: וּשְׁנֵיהֶם מִקְרָא אֶחָד דָּרְשׁוּ, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וַיְהִי יְשַׁעְיָהוּ לֹא יָצָא אֶל חָצֵר הַתִּיכוֹנָה״. כְּתִיב ״הָעִיר״ וְקָרֵינַן ״חָצֵר״ — מִכָּאן לָאִסְטְרַטְיָא שֶׁל מֶלֶךְ שֶׁהָיוּ כַּעֲיָירוֹת בֵּינוֹנִיּוֹת.

Rabbi Yoḥanan said: Both Rabbi Elai and Ḥananya derived their opinion from the same verse, as it is stated: “And it came to pass, before Isaiah was gone out into the middle courtyard, that the word of the Lord came to him, saying” (ii Kings 20:4). In the biblical text, it is written: “The city [ha’ir],” and we read it as: “The middle courtyard [ḥatzer],” as there is a difference in this verse between the written word and how it is spoken. From here it is derived that royal courts were as large as intermediate-sized cities. Consequently, there is no contradiction, as the central courtyard of the royal palace was itself like a small town.

בְּמַאי קָמִיפַּלְגִי? מָר סָבַר: עֲיָירוֹת בֵּינוֹנִיּוֹת הָוְיָין בֵּית כּוֹר. וּמָר סָבַר: אַרְבָּעִים סְאָה הָוְיָין.

The Gemara explains: With regard to what principle do Rabbi Elai and Ḥananya disagree? One Sage, Rabbi Elai, maintains: Intermediate-sized towns are the size of a field that had an area of a beit kor; and one Sage, Ḥananya, maintains: They are the size of forty se’a.

וִישַׁעְיָהוּ מַאי בָּעֵי הָתָם? אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר בַּר חָנָה אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: מְלַמֵּד שֶׁחָלָה חִזְקִיָּה, וְהָלַךְ יְשַׁעְיָהוּ וְהוֹשִׁיב יְשִׁיבָה עַל פִּתְחוֹ.

The Gemara asks about the Biblical narrative cited above: What did Isaiah need to do there in the middle court, i.e., why was he there? The Gemara answers: Rabba bar bar Ḥana said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: This teaches that Hezekiah took ill, and Isaiah went and established a Torah academy at his door, so that Torah scholars would sit and occupy themselves with Torah outside his room, the merit of which would help Hezekiah survive.

מִכָּאן לְתַלְמִיד חָכָם שֶׁחָלָה, שֶׁמּוֹשִׁיבִין יְשִׁיבָה עַל פִּתְחוֹ. וְלָאו מִילְּתָא הִיא, דִּילְמָא אָתֵי לְאִיגָּרוֹיֵי בֵּיהּ שָׂטָן.

Based on this, it is derived, with regard to a Torah scholar who took ill, that one establishes an academy at the entrance to his home. The Gemara comments: This, however, is not a proper course of action, as perhaps they will come to provoke Satan against him. Challenging Satan might worsen the health of a sick person rather than improve it.

וְכֵן שָׁמַעְתִּי הֵימֶנּוּ: אַנְשֵׁי חָצֵר שֶׁשָּׁכַח אֶחָד וְלֹא עֵירַב — בֵּיתוֹ אָסוּר.

The mishna cites another statement made by Rabbi Elai in the name of Rabbi Eliezer: And I also heard from him another halakha: If one of the residents of a courtyard forgot and did not join in an eiruv with the other residents, and on Shabbat he ceded ownership of his share in the courtyard to the other residents, it is prohibited for him, the one who forgot to establish an eiruv, to bring in objects or take them out from his house to the courtyard; but it is permitted to the other residents to bring objects from their houses to that other person’s house via the courtyard, and vice versa.

וְהָתְנַן: בֵּיתוֹ אָסוּר לְהוֹצִיא וּלְהַכְנִיס לוֹ וְלָהֶן?!

The Gemara raises an objection: Didn’t we learn in a mishna: It is prohibited for the one who forgot to establish an eiruv to bring in objects or take them out from his house to the courtyard, and for the other residents who did make an eiruv, to take out objects from the house to the courtyard or to bring them into the house from the courtyard.

אָמַר רַב הוּנָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב יְהוֹשֻׁעַ אָמַר רַב שֵׁשֶׁת: לָא קַשְׁיָא,

Rav Huna, son of Rav Yehoshua, said that Rav Sheshet said: This is not difficult.

הָא רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר, וְהָא רַבָּנַן.

This, the mishna here, is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer, while that, the other mishna, is in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis.

כְּשֶׁתִּימְצֵי לוֹמַר, לְדִבְרֵי רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר: הַמְבַטֵּל רְשׁוּת חֲצֵירוֹ — רְשׁוּת בֵּיתוֹ בִּיטֵּל. לְרַבָּנַן: הַמְבַטֵּל רְשׁוּת חֲצֵירוֹ — רְשׁוּת בֵּיתוֹ לֹא בִּיטֵּל.

Rav Sheshet adds: When you examine the matter closely, you will find that according to the statement of Rabbi Eliezer, one who renounces his authority over his share in the courtyard to the other residents of the courtyard also renounces his authority over his own house. However, according to the opinion of the Rabbis, one who renounces his authority over his share in the courtyard to the other residents does not renounce his authority over his own house to them.

פְּשִׁיטָא!

The Gemara expresses surprise at this comment: But it is obvious that this is the point over which the tanna’im disagree.

אָמַר רַחֲבָה: אֲנָא וְרַב הוּנָא בַּר חִינָּנָא תַּרְגֵּימְנָא: לֹא נִצְרְכָא אֶלָּא לַחֲמִשָּׁה שֶׁשְּׁרוּיִן בְּחָצֵר אֶחָד וְשָׁכַח אֶחָד מֵהֶן וְלֹא עֵירַב.

The Gemara answers: Raḥava said: Both Rav Huna bar Ḥinnana and I explained: Rav Sheshet’s explanation was necessary only with regard to the case of five people who lived in the same courtyard, one of whom forgot to join in an eiruv with the others.

לְדִבְרֵי רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר: כְּשֶׁהוּא מְבַטֵּל רְשׁוּתוֹ, אֵין צָרִיךְ לְבַטֵּל לְכׇל אֶחָד וְאֶחָד.

According to the statement of Rabbi Eliezer, when he renounces his authority, he need not renounce it to each and every one of the residents, as we already know that Rabbi Eliezer holds that one who renounces authority does so in a generous manner, renouncing authority not only of his share in the courtyard, but also of his own house. Consequently, if he is required to renounce authority to many people, we assume that he does so even if this is not explicitly stated.

לְרַבָּנַן: כְּשֶׁהוּא מְבַטֵּל רְשׁוּתוֹ, צָרִיךְ לְבַטֵּל לְכׇל אֶחָד וְאֶחָד.

In contrast, according to the opinion of the Rabbis, when he renounces his authority, it does not suffice that he renounces it in favor of one person; rather, he must explicitly renounce it to each and every one, as we cannot presume that he renounces authority in a generous manner.

כְּמַאן אָזְלָא הָא דְּתַנְיָא: חֲמִשָּׁה שֶׁשְּׁרוּיִן בְּחָצֵר אֶחָד וְשָׁכַח אֶחָד מֵהֶן וְלֹא עֵירַב, כְּשֶׁהוּא מְבַטֵּל רְשׁוּתוֹ, אֵין צָרִיךְ לְבַטֵּל רְשׁוּת לְכׇל אֶחָד וְאֶחָד. כְּמַאן? כְּרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר.

The Gemara continues: In accordance with which tanna is the ruling that was taught in the following baraita? If five people lived in the same courtyard, and one of them forgot and did not join in an eiruv with the other residents, when he renounces his authority, he need not renounce his authority to each and every one of the residents. The Gemara asks: In accordance with whose opinion is it? It is in accordance with Rabbi Eliezer, as explained above.

רַב כָּהֲנָא מַתְנֵי הָכִי. רַב טַבְיוֹמֵי מַתְנֵי הָכִי: כְּמַאן אָזְלָא הָא דְּתַנְיָא: חֲמִשָּׁה שֶׁשְּׁרוּיִם בְּחָצֵר אֶחָד וְשָׁכַח אֶחָד מֵהֶן וְלֹא עֵירַב, כְּשֶׁהוּא מְבַטֵּל רְשׁוּתוֹ אֵינוֹ צָרִיךְ לְבַטֵּל רְשׁוּת לְכׇל אֶחָד וְאֶחָד, כְּמַאן? אָמַר רַב הוּנָא בַּר יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב שֵׁשֶׁת: כְּמַאן? כְּרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר.

Rav Kahana taught the passage this way, as cited above, that it was Raḥava and Rav Huna bar Ḥinnana who applied Rav Sheshet’s explanation to the case of the five people living in the same courtyard. Rav Tavyomei, on the other hand, taught it as follows, that it was Rav Sheshet himself who applied it to that case: In accordance with which tanna is the ruling that was taught in the following baraita? If five people lived in the same courtyard, and one of them forgot and did not join in an eiruv with the other residents, when he renounces his authority, he need not renounce his authority to each and every one of the residents. This statement is in accordance with whose opinion? Rav Huna bar Yehuda said that Rav Sheshet said: In accordance with whom? In accordance with Rabbi Eliezer.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב פָּפָּא לְאַבָּיֵי: לְרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר, אִי אָמַר: לָא מְבַטֵּילְנָא, וּלְרַבָּנַן, אִי אָמַר: מְבַטֵּילְנָא — מַאי?

Rav Pappa said to Abaye: According to the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer, which presumes that one renounces his authority over his house as well, if one who forgot to join in an eiruv with the other residents of the courtyard explicitly stated: I am not renouncing authority of my house, and likewise, according to the opinion of the Rabbis, if he explicitly stated: I am renouncing authority of my house, what is the halakha in such cases?

טַעְמָא דְּרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר מִשּׁוּם דְּקָסָבַר: הַמְבַטֵּל רְשׁוּת חֲצֵירוֹ, רְשׁוּת בֵּיתוֹ בִּיטֵּל. וְהַאי אָמַר: אֲנָא לָא מְבַטֵּילְנָא.

The Gemara clarifies: Is Rabbi Eliezer’s reason because he maintains in general that one who renounces authority over his share in a courtyard to the other residents presumably also renounces to them authority over his own house, but that since this person explicitly stated: I am not renouncing authority of my house, he therefore maintains his authority?

אוֹ דִילְמָא, טַעְמָא דְּרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר מִשּׁוּם דְּבַיִת בְּלָא חָצֵר לָא עֲבִידִי אִינָשֵׁי דְּדָיְירִי. וְכִי קָאָמַר לָא מְבַטֵּילְנָא — לָאו כָּל כְּמִינֵּיהּ, אַף עַל גַּב דְּאָמַר דָּיַירְנָא — לָאו כְּלוּם קָאָמַר.

Or perhaps Rabbi Eliezer’s reason is because people do not generally live in a house without a courtyard, and therefore anyone who renounces authority over his share in a courtyard automatically renounces authority over his own house regardless of what he says. Therefore, when he says: I am not renouncing authority over my house, it is not in his power to do so, as even though he says: I will continue to live in and retain authority over my house, he has said nothing.

וּלְרַבָּנַן, אִי אָמַר: מְבַטֵּילְנָא. מַאי טַעְמָא דְרַבָּנַן? מִשּׁוּם דְּקָסָבְרִי: הַמְבַטֵּל רְשׁוּת חֲצֵירוֹ — רְשׁוּת בֵּיתוֹ לֹא בִּיטֵּל, וְהַאי אֲמַר מְבַטֵּילְנָא.

And the question likewise arises according to the opinion of the Rabbis. If one explicitly stated: I am renouncing authority of my house as well, what is the halakha? Is the reason for the opinion of the Rabbis because they maintain that one who renounces authority over his share in a courtyard to the other residents presumably does not renounce authority over his own house to them, but since this person explicitly stated: I am renouncing authority over my house, the other residents should be permitted to carry?

אוֹ דִילְמָא, טַעְמָא דְרַבָּנַן מִשּׁוּם דְּלָא עֲבִיד אִינִישׁ דִּמְסַלֵּק נַפְשֵׁיהּ לִגְמָרֵי מִבַּיִת וְחָצֵר, וְהָוֵי כִּי אוֹרֵחַ לְגַבַּיְיהוּ. וְהַאי כִּי אָמַר מְבַטֵּילְנָא — לָאו כָּל כְּמִינֵּיהּ קָאָמַר.

Or perhaps the reason for the opinion of the Rabbis is because one does not usually remove himself entirely from a house and courtyard, making himself like a guest among his neighbors. And therefore, when he states: I am renouncing authority over my house, it is not in his power to do so, and his statement is disregarded.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ: בֵּין לְרַבָּנַן בֵּין לְרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר, כֵּיוָן דְּגַלִּי דַּעְתֵּיהּ — גַּלִּי.

Abaye said to Rav Pappa in answer to his question: Both according to the Rabbis and according to Rabbi Eliezer, once one has revealed his wishes, he has revealed them, and everything follows his express wishes.

וְכֵן שָׁמַעְתִּי מִמֶּנּוּ שֶׁיּוֹצְאִים בְּעַרְקַבָּלִין בְּפֶסַח. מַאי עַרְקַבָּלִין? אָמַר רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ: אַצְווֹתָא חָרוּזְיָאתָא.

The mishna records yet another teaching handed down by Rabbi Elai: And I also heard from Rabbi Eliezer another halakha, that one may fulfill his obligation to eat bitter herbs on Passover with arkablin, a certain bitter herb. The Gemara asks: What is arkablin? Reish Lakish said: It is Atzvata ḥaruziyata, a type of fiber that wraps itself around a date palm.

הֲדַרַן עֲלָךְ עוֹשִׂין פַּסִּין

מַתְנִי׳ בַּכֹּל מְעָרְבִין וּמִשְׁתַּתְּפִין, חוּץ מִן הַמַּיִם וּמִן הַמֶּלַח.

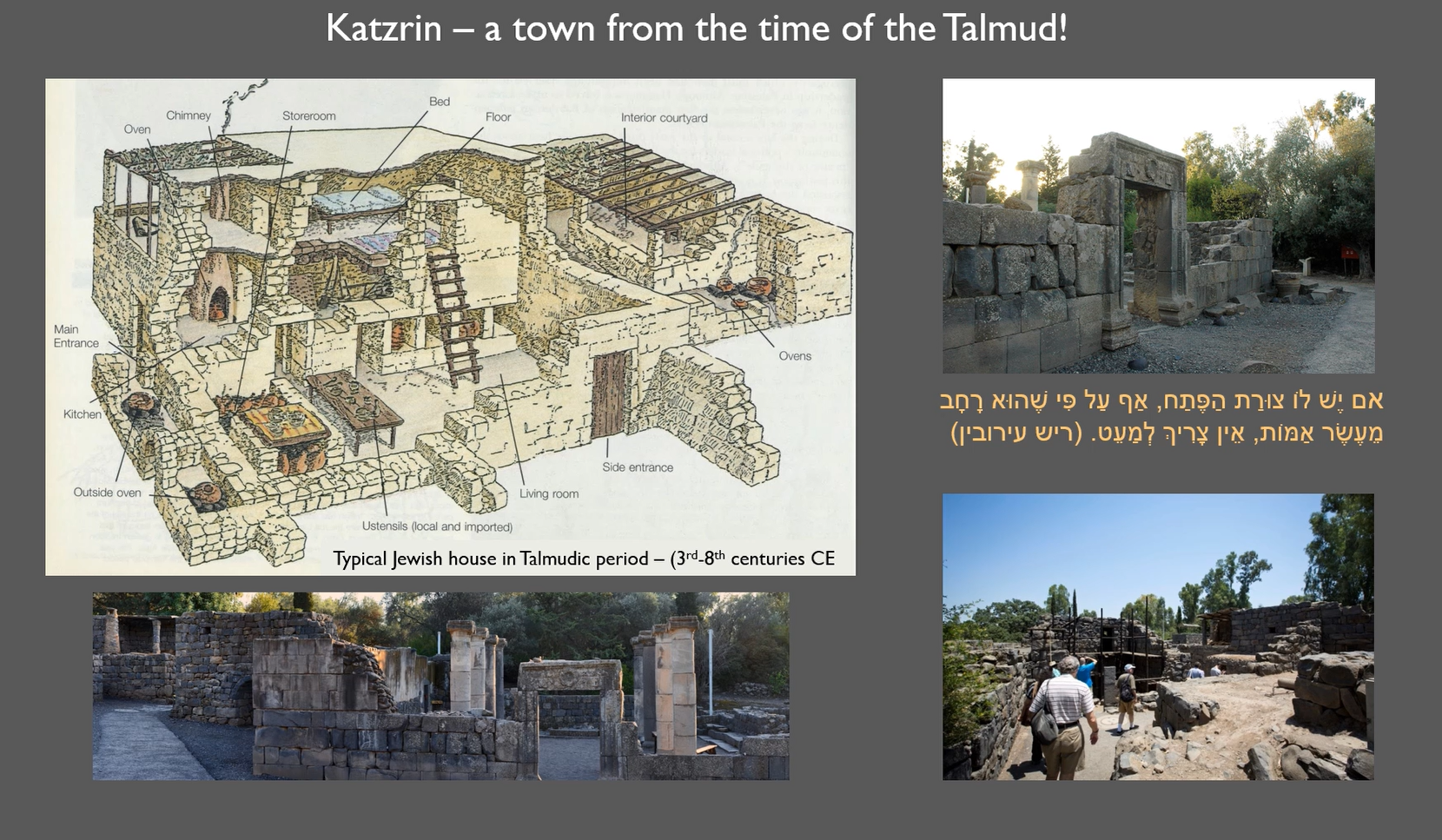

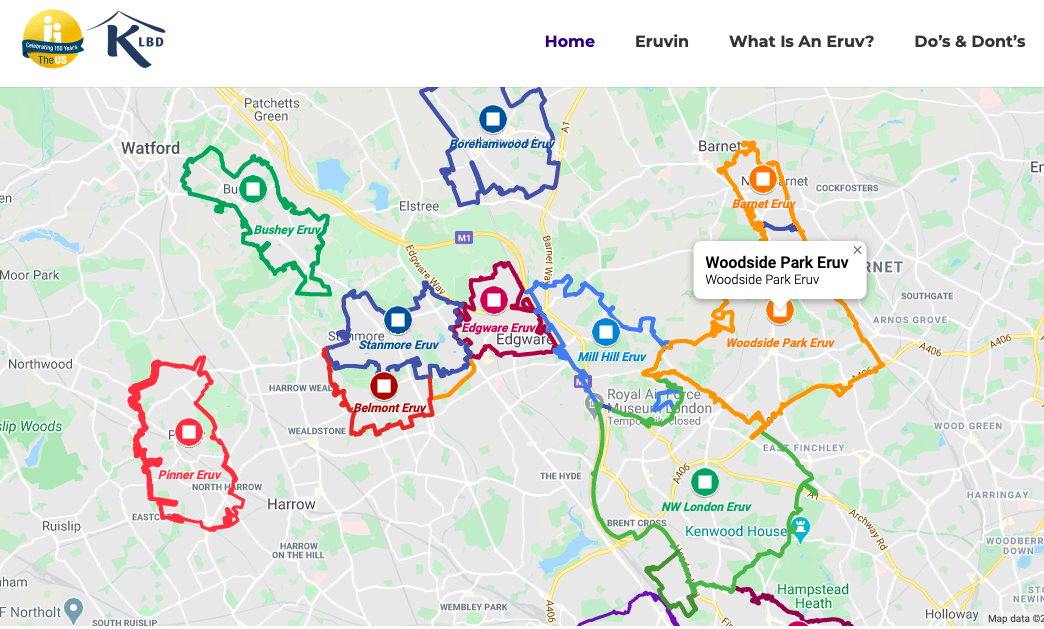

MISHNA: One may establish a joining of houses in courtyards [eiruv ḥatzerot] in order to permit carrying on Shabbat in a courtyard shared by two or more houses, and one may establish a joining of Shabbat borders [eiruv teḥumin] in order to extend the distance one is permitted to walk on Shabbat; and similarly, one may merge courtyards in order to permit carrying in an alleyway shared by two or more courtyards. This may be done with all kinds of food except for water and salt, as they are not considered foods and therefore may not be used for these purposes.

וְהַכֹּל נִיקָּח בְּכֶסֶף מַעֲשֵׂר, חוּץ מִן הַמַּיִם וּמִן הַמֶּלַח. הַנּוֹדֵר מִן הַמָּזוֹן — מוּתָּר בְּמֶלַח וּבְמַיִם.

The mishna continues with two similar principles: All types of food may be bought with second-tithe money, which must be taken to Jerusalem and used to purchase food (Deuteronomy 14:26), except for water and salt. Similarly, one who vows that nourishment is prohibited to him is permitted to eat water and salt, as they are not considered sources of nourishment.

מְעָרְבִין לַנָּזִיר בְּיַיִן וּלְיִשְׂרָאֵל בִּתְרוּמָה. סוֹמְכוֹס אוֹמֵר: בְּחוּלִּין.

It was further stated with regard to the laws of joining courtyards that one may establish an eiruv teḥumin for a nazirite with wine, even though he is prohibited to drink it, because it is permitted to others. And similarly, one may establish an eiruv teḥumin for an Israelite with teruma, even though he may not eat it, because it is permitted to a priest. The food used for an eiruv teḥumin must be fit for human consumption, but it is not essential that it be fit for the consumption of the one for whom it is being used. Summakhos, however, says: One may only establish an eiruv teḥumin for an Israelite with unconsecrated food.

וְלַכֹּהֵן בְּבֵית הַפְּרָס. רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: אֲפִילּוּ בֵּין הַקְּבָרוֹת.

It was additionally stated that one may establish an eiruv teḥumin for a priest in a beit haperas, a field containing a grave that was plowed over. There is doubt as to the location of bone fragments in the entire area. A priest is prohibited to come into contact with a corpse, and therefore may not enter a beit haperas. Rabbi Yehuda says: An eiruv teḥumin may be established for a priest even between the graves in a graveyard, an area which the priest may not enter by Torah law,