Eruvin 46

כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן דְּהָווּ לְהוּ נוֹלָד, דַּאֲסִירִי!

The Gemara raises a difficulty: If the water was previously not in its current state, all the more so should it be considered as something that came into being [nolad] on the Festival, and consequently it is prohibited to carry it. Something that came into being or assumed its present form on Shabbat or Festivals is considered set-aside [muktze] and may not be handled on Shabbat or Festivals.

אֶלָּא: מַיָּא בְּעָבִים מֵינָד נָיְידִי. הַשְׁתָּא דְּאָתֵית לְהָכִי, אוֹקְיָינוֹס נָמֵי לָא לִיקְשׁוֹ לָךְ, מַיָּא בְּאוֹקְיָינוֹס נָמֵי מֵינָד נָיְידִי, וְתַנְיָא: נְהָרוֹת הַמּוֹשְׁכִין וּמַעְיָינוֹת הַנּוֹבְעִין הֲרֵי הֵן כְּרַגְלֵי כׇּל אָדָם.

Rather, we should say: The water in clouds is in constant motion and therefore does not acquire residence there. The Gemara comments: Now that you have arrived at this answer, the ocean should also not be difficult for you, as the water in the ocean is also in constant motion. And it was taught in a baraita: Flowing rivers and streaming springs are like the feet of all people, as their waters do not acquire residence in any particular place. The same law also applies to clouds and seas.

אָמַר רַבִּי יַעֲקֹב בַּר אִידֵּי אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן בֶּן נוּרִי. אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַבִּי זֵירָא לְרַבִּי יַעֲקֹב בַּר אִידִי: בְּפֵירוּשׁ שְׁמִיעַ לָךְ אוֹ מִכְּלָלָא שְׁמִיעַ לָךְ? אֲמַר לֵיהּ: בְּפֵירוּשׁ שְׁמִיעַ לִי.

Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi said that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri, that one who was asleep at the beginning of Shabbat may travel two thousand cubits in every direction. Rabbi Zeira said to Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi: Did you hear this halakha explicitly from Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, or did you understand it by inference from some other ruling that he issued? Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi said to him: I heard it explicitly from him.

מַאי כְּלָלָא? דְּאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: הֲלָכָה כְּדִבְרֵי הַמֵּיקֵל בְּעֵירוּב.

The Gemara asks: From what other teaching could this ruling be inferred? The Gemara explains: From that which Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: The halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion with regard to an eiruv.

וְתַרְתֵּי לְמָה לִי?!

The Gemara asks: Why do I need both? Why was it necessary for Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi to state both the general ruling that the halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion with regard to an eiruv, and also the specific ruling that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri on this issue?

אָמַר רַבִּי זֵירָא: צְרִיכִי, דְּאִי אַשְׁמְעִינַן הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן בֶּן נוּרִי, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא בֵּין לְקוּלָּא וּבֵין לְחוּמְרָא, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן הֲלָכָה כְּדִבְרֵי הַמֵּיקֵל בְּעֵירוּב.

Rabbi Zeira said: Both rulings were necessary, as had he informed us only that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri, I would have said that the halakha is in accordance with him whether this is a leniency, i.e., that a sleeping person acquires residence and may walk two thousand cubits in every direction, or whether it is a stringency, i.e., that ownerless utensils acquire residence and can be carried only two thousand cubits from that place. Consequently, he teaches us that the halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion with regard to an eiruv, so that we rule in accordance with Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri only when it entails a leniency.

וְלֵימָא ״הֲלָכָה כְּדִבְרֵי הַמֵּיקֵל בְּעֵירוּב״. הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן בֶּן נוּרִי לְמָה לִי?

The Gemara asks: Let him state only that the halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion with regard to an eiruv. Why do I need the statement that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri?

אִיצְטְרִיךְ, סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ אָמֵינָא הָנֵי מִילֵּי יָחִיד בִּמְקוֹם יָחִיד וְרַבִּים בִּמְקוֹם רַבִּים, אֲבָל יָחִיד בִּמְקוֹם רַבִּים — אֵימָא לָא.

The Gemara answers: This ruling was necessary as well, for had he informed us only that the halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion with regard to an eiruv, it might have entered your mind to say that this statement applies only to disputes in which a single authority disagrees with another single authority, or several authorities disagree with several other authorities. But when a single authority maintains a lenient opinion against several authorities who maintain a more stringent position, you might have said that we do not rule in his favor. Hence, it was necessary to state that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri although he disputes the Rabbis.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא לְאַבָּיֵי: מִכְּדֵי עֵירוּבִין דְּרַבָּנַן, מָה לִי יָחִיד בִּמְקוֹם יָחִיד, וּמָה לִי יָחִיד בִּמְקוֹם רַבִּים!

Rava said to Abaye: Now, since the laws of eiruvin are rabbinic in origin, what reason is there for me to differentiate between a disagreement of a single authority with a single authority and a disagreement of a single authority with several authorities?

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב פָּפָּא לְרָבָא: וּבִדְרַבָּנַן לָא שָׁנֵי לַן בֵּין יָחִיד בִּמְקוֹם יָחִיד לְיָחִיד בִּמְקוֹם רַבִּים!

Rav Pappa said to Rava: Is there no difference with regard to rabbinic laws between a disagreement of a single authority with a single authority, and a disagreement of a single authority with several authorities?

וְהָתְנַן, רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר אוֹמֵר: כׇּל אִשָּׁה שֶׁעָבְרוּ עָלֶיהָ שָׁלֹשׁ עוֹנוֹת — דַּיָּיהּ שְׁעָתָהּ.

Didn’t we learn in a mishna that Rabbi Elazar says: Any woman who passed three expected menstrual cycles without experiencing bleeding is presumed not to be menstruating. If afterward she sees blood, it is enough that she be regarded as ritually impure due to menstruation from the time that she examined herself and saw that she had a discharge, rather than retroactively for up to twenty-four hours. The Rabbis, however, maintain that this halakha applies only to an older woman or to a woman after childbirth, for whom it is natural to stop menstruating, but not to a normal young woman for whom three periods have passed without bleeding.

וְתַנְיָא: מַעֲשֶׂה וְעָשָׂה רַבִּי כְּרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר. לְאַחַר שֶׁנִּזְכַּר, אָמַר: כְּדַי הוּא רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר לִסְמוֹךְ עָלָיו בִּשְׁעַת הַדְּחָק.

And it was taught in a baraita: It once happened that Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi ruled that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Elazar. After he remembered that Rabbi Elazar’s colleagues disagree with him on this matter and that he had apparently ruled incorrectly, he nonetheless said: Rabbi Elazar is worthy to rely upon in exigent circumstances.

מַאי ״לְאַחַר שֶׁנִּזְכַּר״? אִילֵּימָא: לְאַחַר שֶׁנִּזְכַּר דְּאֵין הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר אֶלָּא כְּרַבָּנַן — בִּשְׁעַת הַדְּחָק הֵיכִי עָבֵיד כְּווֹתֵיהּ!

The Gemara comments: What is the meaning of: After he remembered? If you say that it means after he remembered that the halakha is not in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Elazar but rather in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis, then how could he rule in accordance with him even in exigent circumstances, given that the halakha had been decided against him?

אֶלָּא: דְּלָא אִיתְּמַר הִלְכְתָא לָא כְּרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר וְלָא כְּרַבָּנַן. ״לְאַחַר שֶׁנִּזְכַּר״ דְּלָאו יָחִיד פְּלִיג עֲלֵיהּ אֶלָּא רַבִּים פְּלִיגִי עֲלֵיהּ, אָמַר: כְּדַי הוּא רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר לִסְמוֹךְ עָלָיו בִּשְׁעַת הַדְּחָק.

Rather, it must be that the halakha had not been stated on this matter, neither in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Elazar, nor in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis. And after he remembered that it was not a single authority who disagreed with Rabbi Elazar, but rather several authorities who disagreed with him, he nonetheless said: Rabbi Elazar is worthy to rely upon in exigent circumstances. This demonstrates that even with a dispute that involves a rabbinic decree, such as whether a woman is declared ritually impure retroactively, there is room to distinguish between a disagreement of a single authority and a single authority, and a disagreement of a single authority and several authorities.

אָמַר רַב מְשַׁרְשְׁיָא לְרָבָא, וְאָמְרִי לַהּ רַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק לְרָבָא: וּבִדְרַבָּנַן לָא שָׁנֵי בֵּין יָחִיד בִּמְקוֹם יָחִיד, בֵּין יָחִיד בִּמְקוֹם רַבִּים?

Rav Mesharshiya said to Rava, and some say it was Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak who said to Rava: Is there no difference with regard to rabbinic laws between a disagreement of a single authority with a single authority, and a disagreement of a single authority with several authorities?

וְהָתַנְיָא: שְׁמוּעָה קְרוֹבָה נוֹהֶגֶת שִׁבְעָה וּשְׁלֹשִׁים, רְחוֹקָה אֵינָהּ נוֹהֶגֶת אֶלָּא יוֹם אֶחָד.

Wasn’t it was taught in a baraita: If a person receives a proximate report that one of his close relatives has died, he practices all the customs of the intense seven day mourning period as well as the customs of the thirty day mourning period. But if he receives a distant report, he practices only one day of mourning.

וְאֵי זוֹ הִיא קְרוֹבָה וְאֵיזוֹ הִיא רְחוֹקָה? בְּתוֹךְ שְׁלֹשִׁים — קְרוֹבָה, לְאַחַר שְׁלֹשִׁים — רְחוֹקָה, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: אַחַת שְׁמוּעָה קְרוֹבָה וְאַחַת שְׁמוּעָה רְחוֹקָה נוֹהֶגֶת שִׁבְעָה וּשְׁלֹשִׁים.

What is considered a proximate report, and what is considered a distant report? If the report arrives within thirty days of the close relative’s passing, it is regarded as proximate, and if it arrives after thirty days it is considered distant; this is the statement of Rabbi Akiva. But the Rabbis say: Both in the case of a proximate report and in the case of a distant report, the grieving relative practices the seven-day mourning period and the thirty-day mourning period.

וְאָמַר רַבָּה בַּר בַּר חָנָה אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: כׇּל מָקוֹם שֶׁאַתָּה מוֹצֵא יָחִיד מֵיקֵל וְרַבִּים מֵחֲמִירִין, הֲלָכָה כְּדִבְרֵי הַמַּחְמִירִין הַמְרוּבִּים, חוּץ מִזּוֹ, שֶׁאַף עַל פִּי שֶׁרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא מֵיקֵל וַחֲכָמִים מֵחֲמִירִין — הֲלָכָה כְּדִבְרֵי רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא.

And Rabba bar bar Ḥana said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: Wherever you find that a single authority is lenient with regard to a certain halakha and several other authorities are stringent, the halakha is in accordance with the words of the stringent authorities, who constitute the majority, except for here, where despite the fact that the opinion of Rabbi Akiva is lenient and the opinion of the Rabbis is more stringent, the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Akiva.

וְסָבַר לַהּ כִּשְׁמוּאֵל, דְּאָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: הֲלָכָה כְּדִבְרֵי הַמֵּיקֵל בְּאֵבֶל.

And Rabbi Yoḥanan holds like Shmuel, as Shmuel said: The halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion with regard to mourning practices, i.e., wherever there is a dispute with regard to mourning customs, the halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion.

בַּאֲבֵילוּת הוּא דְּאַקִּילוּ בַּהּ רַבָּנַן, אֲבָל בְּעָלְמָא — אֲפִילּוּ בִּדְרַבָּנַן שָׁנֵי בֵּין יָחִיד בִּמְקוֹם יָחִיד בֵּין יָחִיד בִּמְקוֹם רַבִּים.

From here the Gemara infers: It is only with regard to mourning practices that the Sages were lenient, but in general, with regard to other areas of halakha, even in the case of rabbinic laws there is a difference between a disagreement of a single authority with a single authority and a disagreement of a single authority with several authorities. This being the case, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi did well to rule explicitly that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri, even though he is a single authority who ruled leniently in dispute with the Rabbis.

וְרַב פָּפָּא אָמַר, אִיצְטְרִיךְ, סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ אָמֵינָא: הָנֵי מִילֵּי בְּעֵירוּבֵי חֲצֵירוֹת, אֲבָל בְּעֵירוּבֵי תְחוּמִין — אֵימָא לָא צְרִיכָא.

Rav Pappa said a different explanation for the fact that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi made both statements: It was necessary for Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi to inform us that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri, because had he said only that the halakha follows the lenient opinion with regard to an eiruv, it could have entered your mind to say that this statement applies only with regard to the laws governing the eiruv of courtyards, which are entirely rabbinic in origin. But with regard to the more stringent laws governing the eiruv of Shabbat limits, you would have said that we should not rule leniently, and therefore it was necessary to make both statements.

וּמְנָא תֵּימְרָא דְּשָׁנֵי לַן בֵּין עֵירוּבֵי חֲצֵירוֹת לְעֵירוּבֵי תְּחוּמִין — דִּתְנַן, אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים — בְּעֵירוּבֵי תְחוּמִין, אֲבָל בְּעֵירוּבֵי חֲצֵירוֹת מְעָרְבִין בֵּין לְדַעַת וּבֵין שֶׁלֹּא לְדַעַת, שֶׁזָּכִין לְאָדָם שֶׁלֹּא בְּפָנָיו, וְאֵין חָבִין לְאָדָם אֶלָּא בְּפָנָיו.

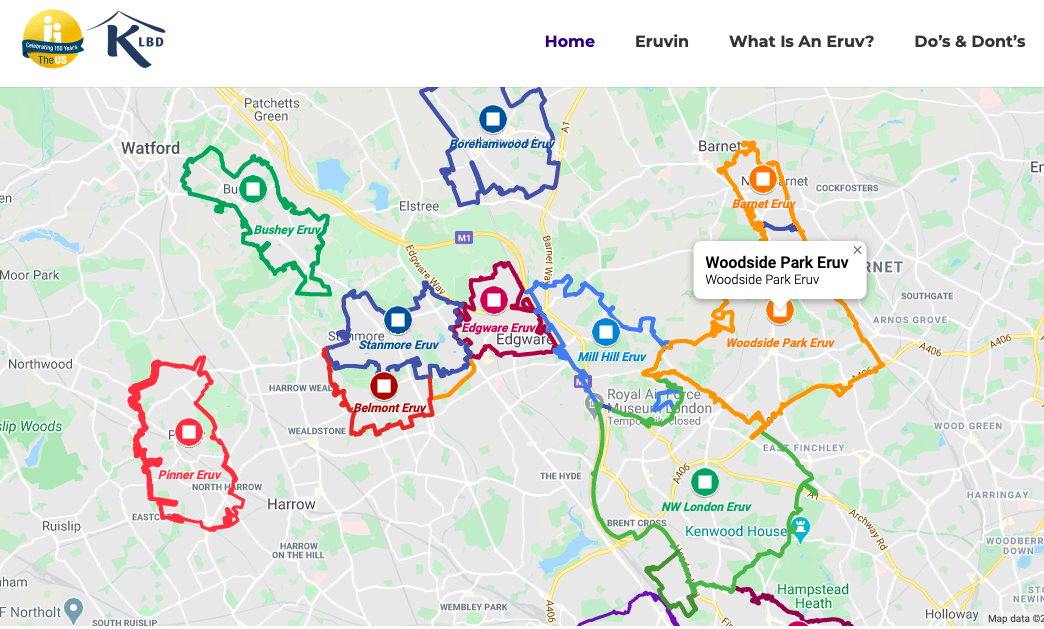

The Gemara asks: And from where do you say that we distinguish between an eiruv of courtyards and an eiruv of Shabbat limits? As we learned in a mishna that Rabbi Yehuda said: In what case is this statement said, that an eiruv may be established for another person only with his knowledge? It was said with regard to an eiruv of Shabbat limits, but with regard to an eiruv of courtyards, an eiruv may be established for another person whether with his knowledge or without his knowledge, as one may act in a person’s interest in his absence; however, one may not act to a person’s disadvantage in his absence. One may act unilaterally on someone else’s behalf when the action is to that other person’s benefit; however, when it is to the other person’s detriment, or when there are both advantages and disadvantages to him, one may act on the other person’s behalf only if one has been explicitly appointed as an agent. Since an eiruv of courtyards is always to a person’s benefit, it can be established even without his knowledge. However, with regard to an eiruv of Shabbat limits, while it enables one to walk in one direction, it disallows him from walking in the opposite direction. Therefore, it can be established only with his knowledge.

רַב אָשֵׁי אָמַר: אִיצְטְרִיךְ, סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ אָמֵינָא, הָנֵי מִילֵּי בְּשִׁיּוּרֵי עֵירוּב, אֲבָל בִּתְחִילַּת עֵירוּב — אֵימָא לָא.

Rav Ashi said that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi’s need to issue two rulings can be explained in another manner: It is necessary for Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi to inform us that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri, as if he had said only that the halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion with regard to an eiruv, it could have entered your mind to say that this statement applies only with regard to the remnants of an eiruv, i.e., an eiruv that had been properly established, where the concern is that it might subsequently have become invalid. But with regard to an initial eiruv, i.e., an eiruv that is just being established and has not yet taken effect, you might have said that we should not rule leniently, and therefore it was necessary to issue both rulings.

וּמְנָא תֵּימְרָא דְּשָׁנֵי לַן בֵּין שִׁיּוּרֵי עֵירוּב לִתְחִילַּת עֵירוּב — דִּתְנַן, אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹסֵי: בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים — בִּתְחִילַּת עֵירוּב, אֲבָל בְּשִׁיּוּרֵי עֵירוּב — אֲפִילּוּ כָּל שֶׁהוּא.

The Gemara asks: And from where do you say that we distinguish between the remnants of an eiruv and an initial eiruv? As we learned in a mishna: Rabbi Yosei said: In what case is this statement said, that the Sages stipulated that a fixed quantity of food is necessary for establishing an eiruv? It is said with regard to an initial eiruv, i.e., when setting up an eiruv for the first time; however, with regard to the remnants of an eiruv, i.e., on a subsequent Shabbat when the measure may have become diminished, even a minimal amount suffices.

וְלֹא אָמְרוּ לְעָרֵב חֲצֵירוֹת, אֶלָּא כְּדֵי שֶׁלֹּא לְשַׁכֵּחַ תּוֹרַת עֵירוּב מִן הַתִּינוֹקוֹת.

And they said to establish an eiruv for courtyards only after all the inhabitants of the city merge their alleyways and become like the inhabitants of a single courtyard, so that the law of eiruv should not be forgotten by the children, who may not be aware of the arrangement that has been made with regard to the alleyways.

רַבִּי יַעֲקֹב וְרַבִּי זְרִיקָא אָמְרוּ: הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא מֵחֲבֵירוֹ, וּכְרַבִּי יוֹסֵי מֵחֲבֵרָיו, וּכְרַבִּי מֵחֲבֵירוֹ.

Since the Gemara discussed the principles cited with regard to halakhic decision-making, it cites additional principles. Rabbi Ya’akov and Rabbi Zerika said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Akiva in disputes with any individual Sage, and the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei even in disputes with other Sages, and the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi in disputes with any individual Sage.

לְמַאי הִלְכְתָא? רַבִּי אַסִּי אָמַר: הֲלָכָה. וְרַבִּי חִיָּיא בַּר אַבָּא אָמַר: מַטִּין. וְרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בְּרַבִּי חֲנִינָא אָמַר: נִרְאִין.

The Gemara asks: With regard to what halakha do these principles apply, meaning, to what degree are they binding? Rabbi Asi said: This is considered binding halakha. And Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba said: One is inclined toward such a ruling in cases where an individual asks, but does not issue it as a public ruling in all cases. And Rabbi Yosei, son of Rabbi Ḥanina, said: It appears that one should rule this way, but it is not an established halakha that is considered binding with regard to issuing rulings.

כַּלָּשׁוֹן הַזֶּה אָמַר רַבִּי יַעֲקֹב בַּר אִידֵּי אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: רַבִּי מֵאִיר וְרַבִּי יְהוּדָה — הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה, רַבִּי יְהוּדָה וְרַבִּי יוֹסֵי — הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי. וְאֵין צָרִיךְ לוֹמַר רַבִּי מֵאִיר וְרַבִּי יוֹסֵי — הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי. הַשְׁתָּא בִּמְקוֹם רַבִּי יְהוּדָה לֵיתָא, בִּמְקוֹם רַבִּי יוֹסֵי מִיבַּעְיָא?!

Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: In the case of a dispute between Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Yehuda, the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda; in the case of a dispute between Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Yosei, the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei; and, needless to say, in the case of a dispute between Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Yosei, the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei. As now, if in disputes with Rabbi Yehuda, the opinion of Rabbi Meir is not accepted as law, need it be stated that in disputes with Rabbi Yosei, Rabbi Meir’s opinion is rejected? Rabbi Yehuda’s opinion is not accepted in disputes with Rabbi Yosei.

אָמַר רַב אַסִּי: אַף אֲנִי לוֹמֵד: רַבִּי יוֹסֵי וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן — הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי, דְּאָמַר רַבִּי אַבָּא אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: רַבִּי יְהוּדָה וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן — הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה. הַשְׁתָּא בִּמְקוֹם רַבִּי יְהוּדָה לֵיתָא, בִּמְקוֹם רַבִּי יוֹסֵי מִיבַּעְיָא?

Rav Asi said: I also learn based on the same principle that in a dispute between Rabbi Yosei and Rabbi Shimon, the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei. As Rabbi Abba said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: In cases of dispute between Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Shimon, the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda. Now, if where it is opposed by Rabbi Yehuda the opinion of Rabbi Shimon is not accepted as law, where it is opposed by the opinion of Rabbi Yosei, with whom the halakha is in accordance against Rabbi Yehuda, is it necessary to say that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei?

אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: רַבִּי מֵאִיר וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן, מַאי? תֵּיקוּ.

The Gemara raises a dilemma: In a dispute between Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Shimon, what is the halakha? No sources were found to resolve this dilemma, and it stands unresolved.

אָמַר רַב מְשַׁרְשְׁיָא: לֵיתַנְהוּ לְהָנֵי כְּלָלֵי. מְנָא לֵיהּ לְרַב מְשַׁרְשְׁיָא הָא?

Rav Mesharshiya said: These principles of halakhic decision-making are not to be relied upon. The Gemara asks: From where does Rav Mesharshiya derive this statement?

אִילֵּימָא מֵהָא דִּתְנַן: רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר לְמָה הַדָּבָר דּוֹמֶה — לְשָׁלֹשׁ חֲצֵירוֹת הַפְּתוּחוֹת זוֹ לָזוֹ וּפְתוּחוֹת לִרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים. עֵירְבוּ שְׁתַּיִם הַחִיצוֹנוֹת עִם הָאֶמְצָעִית — הִיא מוּתֶּרֶת עִמָּהֶן וְהֵן מוּתָּרוֹת עִמָּהּ, וּשְׁתַּיִם הַחִיצוֹנוֹת אֲסוּרוֹת זוֹ עִם זוֹ.

If you say that he derived it from that which we learned in the mishna that Rabbi Shimon said: To what is this comparable? It is like three courtyards that open into one another, and also open into a public domain. If the two outer courtyards established an eiruv with the middle one, the residents of the middle one are permitted to carry to the two outer ones, and they are permitted to carry to it, but the residents of the two outer courtyards are prohibited to carry from one to the other, as they did not establish an eiruv with one another.

וְאָמַר רַב חָמָא בַּר גּוּרְיָא אָמַר רַב: הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן. וּמַאן פְּלִיג עֲלֵיהּ — רַבִּי יְהוּדָה. וְהָא אָמְרַתְּ: רַבִּי יְהוּדָה וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן — הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה. אֶלָּא לָאו שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ: לֵיתַנְהוּ?

And Rav Ḥama bar Gurya said that Rav said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Shimon; and who disagrees with Rabbi Shimon on this matter? It is Rabbi Yehuda. Didn’t you say: In disputes between Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Shimon, the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda? Rather, can we not conclude from this mishna that these principles should not be relied upon?

וּמַאי קוּשְׁיָא, דִּילְמָא הֵיכָא דְּאִיתְּמַר — אִיתְּמַר, הֵיכָא דְּלָא אִיתְּמַר — לָא אִיתְּמַר.

The Gemara rejects this argument: What is the difficulty posed by this ruling? Perhaps where it is stated explicitly to the contrary, it is stated, but where it is not stated explicitly to the contrary, it is not stated, and these principles apply.

אֶלָּא, מֵהָא דִּתְנַן: עִיר שֶׁל יָחִיד וְנַעֲשֵׂית שֶׁל רַבִּים — מְעָרְבִין אֶת כּוּלָּהּ. שֶׁל רַבִּים וְנַעֲשֵׂית שֶׁל יָחִיד — אֵין מְעָרְבִין אֶת כּוּלָּהּ אֶלָּא אִם כֵּן עוֹשֶׂה חוּצָה לָהּ, כָּעִיר חֲדָשָׁה שֶׁבִּיהוּדָה שֶׁיֵּשׁ בָּהּ חֲמִשִּׁים דָּיוֹרִין — דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי יְהוּדָה.

Rather, the proof is from that which we learned elsewhere in a mishna: If a city that belongs to a single individual subsequently becomes one that belongs to many people, one may establish an eiruv of courtyards for all of it. But if the city belongs to many people, and it falls into the possession of a single individual, one may not establish an eiruv for all of it, unless he excludes from the eiruv an area the size of the town of Ḥadasha in Judea, which contains fifty residents; this is the statement of Rabbi Yehuda.

רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר:

Rabbi Shimon says: