Eruvin 53

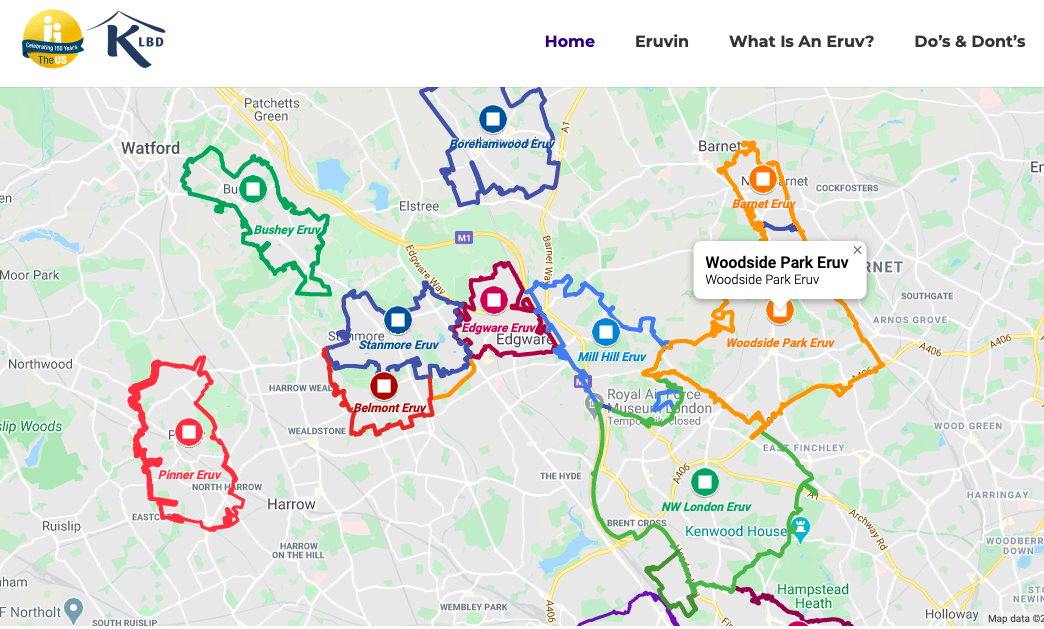

וּגְשָׁרִים וּנְפָשׁוֹת שֶׁיֵּשׁ בָּהֶן בֵּית דִּירָה — מוֹצִיאִין אֶת הַמִּדָּה כְּנֶגְדָּן. וְעוֹשִׂין אוֹתָהּ כְּמִין טַבְלָא מְרוּבַּעַת, כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּהֵא נִשְׂכָּר אֶת הַזָּוִיּוֹת.

and bridges and monuments over graves in which there is a residence, one extends the measure of that side of the city as though there were other structures opposite them in the adjacent corner of the city. And prior to measuring the Shabbat limit, one renders the city like a square tablet so that it gains the corners, although there are actually no houses in those corners.

גְּמָ׳ רַב וּשְׁמוּאֵל: חַד תָּנֵי ״מְעַבְּרִין״ וְחַד תָּנֵי ״מְאַבְּרִין״.

GEMARA: The Gemara cites a dispute with regard to the mishna’s terminology. Rav and Shmuel disagreed: One taught that the term in the mishna is me’abberin, with the letter ayin, and one taught that the term in the mishna is me’abberin, with the letter alef.

מַאן דְּתָנֵי ״מְאַבְּרִין״ — אֵבֶר אֵבֶר, וּמַאן דְּתָנֵי ״מְעַבְּרִין״ — כְּאִשָּׁה עוּבָּרָהּ.

The Gemara explains: The one who taught me’abberin with an alef explained the term in the sense of limb [ever] by limb. Determination of the city’s borders involves the addition of limbs to the core section of the city. And the one who taught me’abberin with an ayin explained the term in the sense of a pregnant woman [ubbera] whose belly protrudes. In similar fashion, all the city’s protrusions are incorporated in its Shabbat limit.

מְעָרַת הַמַּכְפֵּלָה, רַב וּשְׁמוּאֵל, חַד אָמַר: שְׁנֵי בָתִּים זֶה לִפְנִים מִזֶּה, וְחַד אָמַר: בַּיִת וַעֲלִיָּיה עַל גַּבָּיו.

Apropos this dispute, the Gemara cites similar disputes between Rav and Shmuel. With regard to the Machpelah Cave, in which the Patriarchs and Matriarchs are buried, Rav and Shmuel disagreed. One said: The cave consists of two rooms, one farther in than the other. And one said: It consists of a room and a second story above it.

בִּשְׁלָמָא לְמַאן דְּאָמַר זֶה עַל גַּב זֶה — הַיְינוּ ״מַכְפֵּלָה״. אֶלָּא לְמַאן דְּאָמַר שְׁנֵי בָתִּים זֶה לִפְנִים מִזֶּה, מַאי ״מַכְפֵּלָה״?

The Gemara asks: Granted, this is understandable according to the one who said the cave consists of one room above the other, as that is the meaning of Machpelah, double. However, according to the one who said it consists of two rooms, one farther in than the other, in what sense is it Machpelah? Even ordinary houses contain two rooms.

שֶׁכְּפוּלָה בְּזוּגוֹת. ״מַמְרֵא קִרְיַת אַרְבַּע״, אָמַר רַבִּי יִצְחָק, קִרְיַת הָאַרְבַּע זוּגוֹת: אָדָם וְחַוָּה, אַבְרָהָם וְשָׂרָה, יִצְחָק וְרִבְקָה, יַעֲקֹב וְלֵאָה.

Rather, it is called Machpelah in the sense that it is doubled with the Patriarchs and Matriarchs, who are buried there in pairs. This is similar to the homiletic interpretation of the alternative name for Hebron mentioned in the Torah: “Mamre of Kiryat Ha’Arba, which is Hebron” (Genesis 35:27). Rabbi Yitzḥak said: The city is called Kiryat Ha’Arba, the city of four, because it is the city of the four couples buried there: Adam and Eve, Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, and Jacob and Leah.

״וַיְהִי בִּימֵי אַמְרָפֶל״, רַב וּשְׁמוּאֵל, חַד אָמַר: נִמְרוֹד שְׁמוֹ. וְלָמָּה נִקְרָא שְׁמוֹ אַמְרָפֶל? שֶׁאָמַר וְהִפִּיל לְאַבְרָהָם אָבִינוּ בְּתוֹךְ כִּבְשַׁן הָאֵשׁ, וְחַד אָמַר: אַמְרָפֶל שְׁמוֹ, וְלָמָּה נִקְרָא שְׁמוֹ נִמְרוֹד? שֶׁהִמְרִיד אֶת כָּל הָעוֹלָם כּוּלּוֹ עָלָיו בְּמַלְכוּתוֹ.

They disagreed about this verse as well: “And it came to pass in the days of Amraphel” (Genesis 14:1). Rav and Shmuel both identified Amraphel with Nimrod. However, one said: Nimrod was his name. And why was his name called Amraphel? It is a contraction of two Hebrew words: As he said [amar] the command and cast [hippil] our father Abraham into the fiery furnace, when Abraham rebelled against and challenged his proclaimed divinity. And one said: Amraphel was his name. And why was his name called Nimrod? Because he caused the entire world to rebel [himrid] against God during his reign.

״וַיָּקׇם מֶלֶךְ חָדָשׁ עַל מִצְרָיִם״, רַב וּשְׁמוּאֵל, חַד אָמַר: חָדָשׁ מַמָּשׁ, וְחַד אָמַר: שֶׁנִּתְחַדְּשׁוּ גְּזֵירוֹתָיו.

They also disagreed about this verse: “There arose a new king over Egypt, who knew not Joseph” (Exodus 1:8). Rav and Shmuel disagreed. One said: He was actually a new king, and one said: He was in fact the old king, but his decrees were new.

מַאן דְּאָמַר חָדָשׁ מַמָּשׁ — דִּכְתִיב ״חָדָשׁ״, וּמַאן דְּאָמַר שֶׁנִּתְחַדְּשׁוּ גְּזֵירוֹתָיו — מִדְּלָא כְּתִיב ״וַיָּמׇת וַיִּמְלוֹךְ״.

The Gemara explains. The one who said he was actually a new king based his opinion on the fact that it is written in the verse that he was new. And the one who said that his decrees were new derived his opinion from the fact that it is not written: And the king died, and his successor reigned, as it is written, for example, with regard to the kings of Edom (Genesis 36).

וּלְמַאן דְּאָמַר שֶׁנִּתְחַדְּשׁוּ גְּזֵירוֹתָיו, הָא כְתִיב ״אֲשֶׁר לֹא יָדַע אֶת יוֹסֵף״? מַאי ״אֲשֶׁר לֹא יָדַע אֶת יוֹסֵף״ — דַּהֲוָה דָּמֵי כְּמַאן דְּלָא יָדַע לֵיהּ לְיוֹסֵף כְּלָל.

The Gemara asks: And according to the one who said that his decrees were new, isn’t it written: “Who knew not Joseph”? If it were the same king, how could he not know Joseph? The Gemara explains: What is the meaning of the phrase: “Who knew not Joseph”? It means that he conducted himself like one who did not know Joseph at all.

(סִימָן: שְׁמוֹנֶה עֶשְׂרֵה וּשְׁנֵים עָשָׂר לָמַדְנוּ בְּדָוִד וַיִּבֶן.)

The Gemara cites a mnemonic of key words from a series of traditions cited below: Eighteen and twelve we studied, with regard to David, and he will understand.

אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: שְׁמוֹנָה עָשָׂר יָמִים גִּידַּלְתִּי אֵצֶל רַבִּי אוֹשַׁעְיָא בְּרִיבִּי וְלֹא לָמַדְתִּי מִמֶּנּוּ אֶלָּא דָּבָר אֶחָד בְּמִשְׁנָתֵינוּ: כֵּיצַד מְאַבְּרִין אֶת הֶעָרִים — בְּאָלֶף.

Rabbi Yoḥanan said: I spent eighteen days with Rabbi Oshaya the Distinguished [Beribbi], and I learned from him only one matter in our Mishna. In the phrase: How does one extend cities, the word me’abberin is spelled with an alef.

אִינִי?! וְהָאָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן שְׁנֵים עָשָׂר תַּלְמִידִים הָיוּ לוֹ לְרַבִּי אוֹשַׁעְיָא בְּרִיבִּי, וּשְׁמוֹנָה עָשָׂר יָמִים גִּידַּלְתִּי בֵּינֵיהֶן, וְלָמַדְתִּי לֵב כׇּל אֶחָד וְאֶחָד, וְחׇכְמַת כׇּל אֶחָד וְאֶחָד?

The Gemara asks: Is this so? Didn’t Rabbi Yoḥanan say: Rabbi Oshaya the Distinguished had twelve students, and I spent eighteen days among them, and I learned the heart of each and every one, i.e., the nature and character of each student, and the extent of the wisdom of each and every one? How could Rabbi Yoḥanan say that he learned only one matter?

לֵב כׇּל אֶחָד וְאֶחָד וְחׇכְמַת כׇּל אֶחָד וְאֶחָד גְּמַר, גְּמָרָא — לָא גְּמַר. אִיבָּעֵית אֵימָא: מִנַּיְיהוּ דִּידְהוּ — גְּמַר, מִינֵּיהּ דִּידֵיהּ — לָא גְּמַר. וְאִיבָּעֵית אֵימָא: דָּבָר אֶחָד בְּמִשְׁנָתֵינוּ קָאָמַר.

The Gemara answers: It is possible that he learned the heart of each and every one and the wisdom of each and every one, but he did not learn substantive tradition. And if you wish, say instead: From the students themselves he learned many things; from Rabbi Oshaya himself he did not learn anything beyond that one matter. And if you wish, say instead: Rabbi Yoḥanan meant to say that he learned only one matter in our Mishna from Rabbi Oshaya, but he learned other matters from him based on baraitot and other sources.

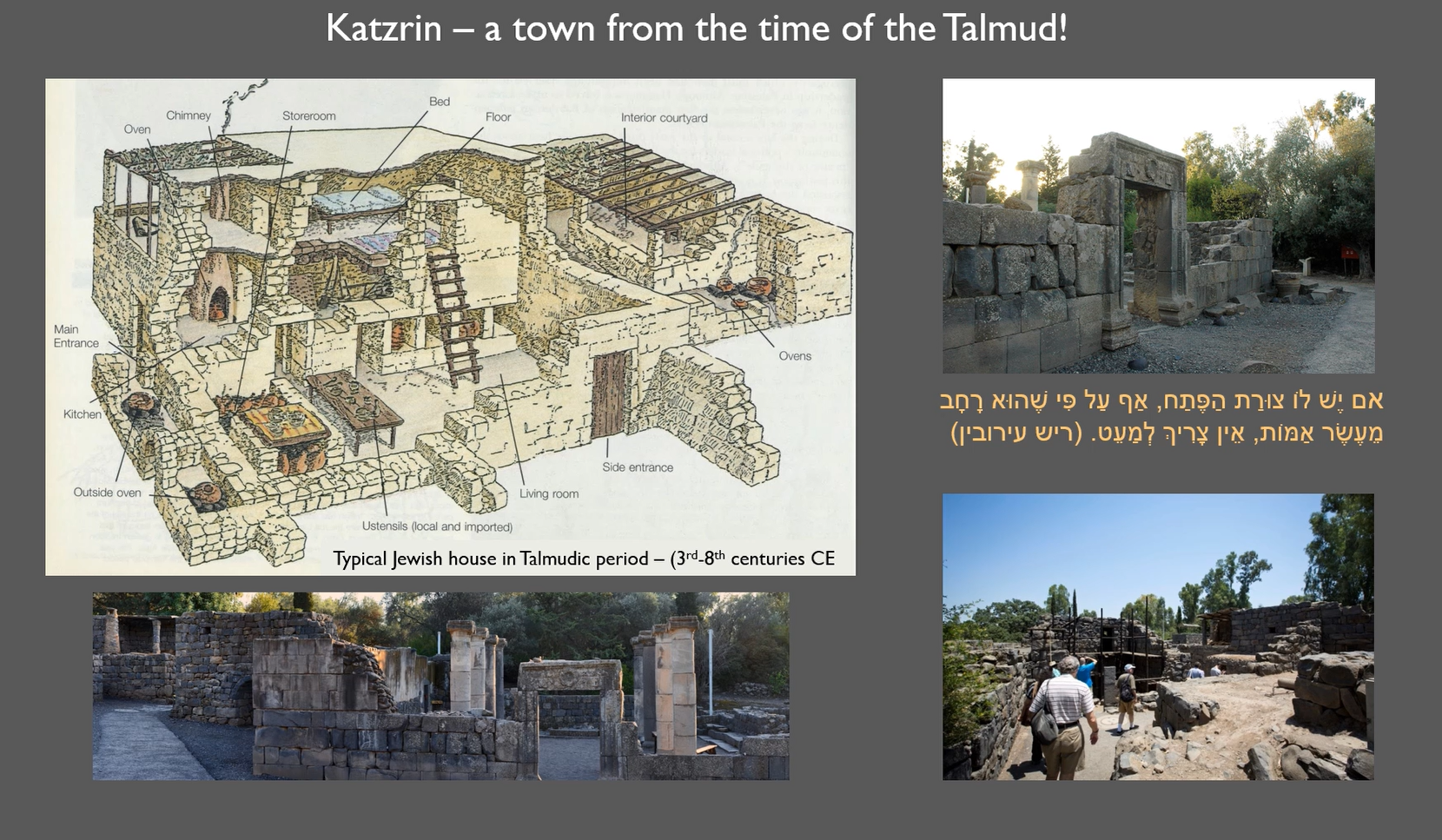

וְאָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: כְּשֶׁהָיִינוּ לוֹמְדִין תּוֹרָה אֵצֶל רַבִּי אוֹשַׁעְיָא, הָיִינוּ יוֹשְׁבִין אַרְבָּעָה אַרְבָּעָה בְּאַמָּה. אָמַר רַבִּי: כְּשֶׁהָיִינוּ לוֹמְדִין תּוֹרָה אֵצֶל רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בֶּן שַׁמּוּעַ, הָיִינוּ יוֹשְׁבִין שִׁשָּׁה שִׁשָּׁה בְּאַמָּה.

And Rabbi Yoḥanan said about that period: When we were studying Torah with Rabbi Oshaya, it was so crowded with students that we would sit four in each square cubit. Similarly, Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi said: When we were studying Torah with Rabbi Elazar ben Shamua, we would sit six in each square cubit.

אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: רַבִּי אוֹשַׁעְיָא בְּרִיבִּי בְּדוֹרוֹ כְּרַבִּי מֵאִיר בְּדוֹרוֹ, מָה רַבִּי מֵאִיר בְּדוֹרוֹ לֹא יָכְלוּ חֲבֵרָיו לַעֲמוֹד עַל סוֹף דַּעְתּוֹ — אַף רַבִּי אוֹשַׁעְיָא לֹא יָכְלוּ חֲבֵרָיו לַעֲמוֹד עַל סוֹף דַּעְתּוֹ.

Rabbi Yoḥanan said about his teacher: Rabbi Oshaya the Distinguished was as great in his generation as Rabbi Meir was in his generation: Just as with regard to Rabbi Meir, in his generation his colleagues were unable to fully grasp the profundity of his thinking due to the subtlety of his great mind, so it was with Rabbi Oshaya; his colleagues were unable to fully grasp the profundity of his thinking.

אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: לִבָּן שֶׁל רִאשׁוֹנִים כְּפִתְחוֹ שֶׁל אוּלָם, וְשֶׁל אַחֲרוֹנִים כְּפִתְחוֹ שֶׁל הֵיכָל, וְאָנוּ — כִּמְלֹא נֶקֶב מַחַט סִידְקִית.

Similarly, Rabbi Yoḥanan said: The hearts, i.e., the wisdom, of the early Sages were like the doorway to the Entrance Hall of the Temple, which was twenty by forty cubits, and the hearts of the later Sages were like the doorway to the Sanctuary, which was ten by twenty cubits. And we, i.e., our hearts, are like the eye of a fine needle.

רִאשׁוֹנִים — רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא, אַחֲרוֹנִים — רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בֶּן שַׁמּוּעַ. אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי: רִאשׁוֹנִים — רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בֶּן שַׁמּוּעַ, אַחֲרוֹנִים — רַבִּי אוֹשַׁעְיָא בְּרִיבִּי. וְאָנוּ כִּמְלֹא נֶקֶב מַחַט סִידְקִית.

He explains: The term early Sages is referring to Rabbi Akiva, and the term later Sages is referring to his student, Rabbi Elazar ben Shamua. Some say that the term early Sages refers to Rabbi Elazar ben Shamua and that the term the later Sages refers to Rabbi Oshaya the Distinguished. And we are like the eye of a fine needle.

אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: וַאֲנַן, כִּי סִיכְּתָא בְּגוּדָּא לִגְמָרָא. אָמַר רָבָא: וַאֲנַן, כִּי אֶצְבַּעְתָּא בְּקִירָא לִסְבָרָא. אָמַר רַב אָשֵׁי: אֲנַן, כִּי אֶצְבַּעְתָּא בְּבֵירָא לְשִׁכְחָה.

On the topic of the steady decline of the generations, Abaye said: And we, as far as our capabilities are concerned, are like a peg in the wall with regard to Torah study. Just as a peg enters a wall with difficulty, our studies penetrate our minds only with difficulty. Rava said: And we are like a finger in wax [kira] with regard to logical reasoning. A finger is not easily pushed into wax, and it extracts nothing from the wax. Rav Ashi said: We are like a finger in a pit with regard to forgetfulness. Just as a finger easily enters a large pit, similarly, we quickly forget our studies.

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב: בְּנֵי יְהוּדָה שֶׁהִקְפִּידוּ עַל לְשׁוֹנָם, נִתְקַיְּימָה תּוֹרָתָם בְּיָדָם. בְּנֵי גָלִיל שֶׁלֹּא הִקְפִּידוּ עַל לְשׁוֹנָם, לֹא נִתְקַיְּימָה תּוֹרָתָם בְּיָדָם.

The Gemara continues the discussion relating to study and comprehension, and cites that which Rav Yehuda said that Rav said: With regard to the people of Judea, who were particular in their speech and always made certain that it was both precise and refined, their Torah knowledge endured for them; with regard to the people of the Galilee, who were not particular in their speech, their Torah knowledge did not endure for them.

מִידֵּי בִּקְפֵידָא תַּלְיָא מִילְּתָא? אֶלָּא: בְּנֵי יְהוּדָה דְּדָיְיקִי לִישָּׁנָא, וּמַתְנְחִי לְהוּ סִימָנָא, נִתְקַיְּימָה תּוֹרָתָן בְּיָדָן. בְּנֵי גָלִיל דְּלָא דָּיְיקִי לִישָּׁנָא, וְלָא מַתְנְחִי לְהוּ סִימָנָא, לֹא נִתְקַיְּימָה תּוֹרָתָן בְּיָדָם.

The Gemara asks: Is this matter at all dependent on being particular with one’s language? Rather, with regard to the people of Judea, who were precise in their language and who would formulate mnemonics for their studies, their Torah knowledge endured for them; with regard to the people of the Galilee, who were not precise in their language and who would not formulate mnemonics, their Torah knowledge did not endure for them.

בְּנֵי יְהוּדָה גְּמַרוּ מֵחַד רַבָּה, נִתְקַיְּימָה תּוֹרָתָן בְּיָדָם. בְּנֵי גָלִיל דְּלָא גָּמְרִי מֵחַד רַבָּה, לֹא נִתְקַיְּימָה תּוֹרָתָן בְּיָדָם.

Furthermore, with regard to the people of Judea, who studied from one teacher, their Torah knowledge endured for them, as their teacher provided them with a consistent approach; however, with regard to the people of the Galilee, who did not study from one teacher, but rather from several teachers, their Torah knowledge did not endure for them, as it was a combination of the approaches and opinions of a variety of Sages.

רָבִינָא אָמַר: בְּנֵי יְהוּדָה דְּגַלּוֹ מַסֶּכְתָּא, נִתְקַיְּימָה תּוֹרָתָן בְּיָדָם. בְּנֵי גָלִיל דְּלָא גַּלּוֹ מַסֶּכְתָּא, לֹא נִתְקַיְּימָה תּוֹרָתָן בְּיָדָם.

Ravina said: With regard to the people of Judea, who would publicly disclose the tractate to be studied in the coming term so that everyone could prepare and study it in advance (ge’onim), their Torah knowledge endured for them; with regard to the people of the Galilee, who would not disclose the tractate to be studied in the coming term, their Torah knowledge did not endure for them.

דָּוִד גַּלִּי מַסֶּכְתָּא, שָׁאוּל לָא גַּלִּי מַסֶּכְתָּא. דָּוִד דְּגַלִּי מַסֶּכְתָּא, כְּתִיב בֵּיהּ: ״יְרֵאֶיךָ יִרְאוּנִי וְיִשְׂמָחוּ״. שָׁאוּל דְּלָא גַּלִּי מַסֶּכְתָּא, כְּתִיב בֵּיהּ: ״(אֶל כׇּל) אֲשֶׁר יִפְנֶה

The Gemara relates that King David would disclose the tractate to be studied in advance, whereas Saul would not disclose the tractate to be studied. With regard to David, who would disclose the tractate, it is written: “Those who fear You will see me and be glad” (Psalms 119:74), since all were prepared and could enjoy his Torah. With regard to Saul, who would not disclose the tractate to be studied, it is written: “And wherever he turned himself

יַרְשִׁיעַ״.

he did them mischief” (i Samuel 14:47).

וְאָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: מִנַּיִין שֶׁמָּחַל לוֹ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא עַל אוֹתוֹ עָוֹן — שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״מָחָר אַתָּה וּבָנֶיךָ עִמִּי״. עִמִּי — בִּמְחִיצָתִי.

The Gemara concludes the mention of Saul on a positive note. And Rabbi Yoḥanan said: From where is it derived that the Holy One, Blessed be He, forgave him for that sin, the massacre of Nov, the city of priests? As it is stated that the spirit of Samuel said to him: “And the Lord will also deliver Israel with you into the hand of the Philistines, and tomorrow shall you and your sons be with me” (i Samuel 28:19); the phrase “with me” means within my partition together with me in heaven, i.e., on the same level as the righteous prophet Samuel.

אָמַר רַבִּי אַבָּא: אִי אִיכָּא דִּמְשַׁאֵיל לְהוּ לִבְנֵי יְהוּדָה דְּדָיְיקִי לִשָּׁנֵי — מְאַבְּרִין תְּנַן אוֹ מְעַבְּרִין תְּנַן, אַכּוּזוֹ תְּנַן אוֹ עַכּוּזוֹ תְּנַן, יָדְעִי.

The Gemara returns to the earlier question with regard to the correct reading of the word me’abberin. Rabbi Abba said: If there is anyone who can ask the people of Judea, who are precise in their language, whether the term in the mishna that we learned is me’abberin with an alef or me’abberin with an ayin, he should ask them. Similarly, with regard to the blemishes of a firstborn animal, was the term meaning its hindquarters that we learned in the mishna akkuzo with an alef, or did we learn akkuzo with an ayin? They would know.

שְׁאֵילִינְהוּ וְאָמְרִי לֵיהּ: אִיכָּא דְּתָנֵי מְאַבְּרִין, וְאִיכָּא דְּתָנֵי מְעַבְּרִין. אִיכָּא דְּתָנֵי אַכּוּזוֹ וְאִיכָּא דְּתָנֵי עַכּוּזוֹ.

The Gemara answers: One asked the people of Judea, and they said to him: Some teach me’abberin with an alef, and some teach me’abberin with an ayin. Some teach akkuzo with an alef, and some teach akkuzo with an ayin. Both versions are well founded and neither one is erroneous.

בְּנֵי יְהוּדָה דָּיְיקִי לִישָּׁנָא מַאי הִיא? דְּהָהוּא בַּר יְהוּדָה דַּאֲמַר לְהוּ: טַלִּית יֵשׁ לִי לִמְכּוֹר. אֲמַרוּ לֵיהּ: מַאי גּווֹן טַלִּיתְךָ? אֲמַר לְהוּ: כִּתְרָדִין עֲלֵי אֲדָמָה.

Having mentioned that the people of Judea are precise in their speech, the Gemara asks: What is the meaning of this? The Gemara answers with an example: As in the case of a certain person from Judea who said to those within earshot: I have a cloak to sell. They said to him: What color is your cloak? He said to them: Like beets on the ground, providing an exceedingly precise description of the exact shade of the cloak, the green tint of beet greens when they first sprout.

בְּנֵי גָלִיל דְּלָא דָּיְיקִי לִישָּׁנָא מַאי הִיא? (דְּתַנְיָא) דְּהָהוּא בַּר גָּלִילָא [דַּהֲוָה קָאָזֵיל] וַאֲמַר לְהוּ: ״אֲמַר לְמַאן, אֲמַר לְמַאן?״ אֲמַרוּ לֵיהּ: גָּלִילָאָה שׁוֹטֶה, חֲמַר לְמִירְכַּב אוֹ חֲמַר לְמִישְׁתֵּי? עֲמַר לְמִילְבַּשׁ אוֹ אִימַּר לְאִיתְכַּסָּאָה?

The Gemara returns to the people of the Galilee, who are not precise in their speech. What is the meaning of this? The Gemara cites examples: As it was taught in a baraita that there was a certain person from the Galilee who would walk and say to people: Who has amar? Who has amar? They said to him: Foolish Galilean, what do you mean? Galileans did not pronounce the guttural letters properly, so it was unclear whether he sought a donkey [ḥamor] to ride, or wine [ḥamar] to drink, wool [amar] to wear, or a lamb [imar] to slaughter. This is an example of the lack of precision in the Galileans’ speech.

הָהִיא אִיתְּתָא דְּבָעֲיָא לְמֵימַר לַחֲבֶרְתַּהּ: ״תָּאִי דְּאוֹכְלִיךְ חֲלָבָא״, אֲמַרָה לַהּ: ״שְׁלוּכָתִי, תּוֹכְלִיךָ לָבִיא״.

The Gemara cites another example of the lack of linguistic precision of the Galileans: There was a certain woman who wanted to say to her friend: My neighbor, come and I will feed you milk [ta’i de’okhlikh ḥelba]; however, due to the imprecise articulation of her words, she said to her: My neighbor, may a lioness eat you [tokhlikh lavya].

הַהִיא אִתְּתָא דְּאָתְיָא לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּדַיָּינָא, אֲמַרָה לֵיהּ: ״מָרִי כִּירִי, תַּפְלָא הֲוָית לִי וְגַנְבוּךְ מִין. וְכַדּוּ הֲווֹת, דְּכַד שָׁדְרוּ לָךְ עִילָּוַיהּ — לָא מָטֵי כַּרְעָיךְ אַאַרְעָא״.

The Gemara cites another example of the ignorance and incivility of the Galileans: There was a certain woman who came before a judge intending to say: Master, sir [Mari kiri, spelled with a kuf], I had a board, and they stole it from me [tavla havet li ugenavuha mimeni]. But instead she said to him: Master, servant [Mari kiri, spelled with a kaf], I had a beam and they stole you from me [tafla havet li ugenavukh min]. And it was so large, that when they would hang you upon it, your feet would not reach the ground.

אַמְהֲתָא דְּבֵי רַבִּי כִּי הֲוָה מִשְׁתַּעְיָא בִּלְשׁוֹן חׇכְמָה, אָמְרָה הָכִי: עֶלֶת נְקַפַת בְּכַד, יִדְאוֹן נִישְׁרַיָּא לְקִינֵּיהוֹן.

In contrast to the speech of the Galileans, which indicates ignorance and loutishness, the Gemara cites examples of the clever phraseology of the inhabitants of Judea and the Sages: The maidservant in the house of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, when she would speak enigmatically, employing euphemistic terminology or in riddles, she would say as follows: The ladle used for drawing wine from the jug is already knocking against the bottom of the jug, i.e., the wine jug is almost empty. Let the eagles fly to their nests, i.e., let the students return home, as there is nothing left for them to drink.

וְכַד הֲוָה בָּעֵי דְּלִיתְּבוּן, הֲוָה אָמְרָה לְהוּ: יִעְדֵּי בָּתַר חֲבֶרְתַּהּ מִינַּהּ, וְתִתְקְפֵי עֶלֶת בְּכַד, כְּאִילְפָא דְּאָזְלָא בְּיַמָּא.

And when Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi wanted them to sit, she would say to them: Let us remove the stopper from another jug, and let the ladle float in the jug like a ship sailing in the sea.

רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר אָסְיָין כִּי הֲוָה מִשְׁתַּעֵי בִּלְשׁוֹן חׇכְמָה, אֲמַר: עֲשׂוּ לִי שׁוֹר בְּמִשְׁפָּט בְּטוּר מִסְכֵּן.

The Gemara also relates that when Rabbi Yosei bar Asyan would speak enigmatically, he would say: Prepare for me an ox in judgment on a poor mountain. His method was to construct words by combining words from Aramaic translations of Hebrew words or Hebrew translations of Aramaic words. Ox is tor in Aramaic; judgment is din. Combined they form teradin, beets. Mountain in Hebrew is har, which they pronounced ḥar; poor is dal. Together it spells ḥardal, mustard. Thus, Rabbi Yosei bar Asyan was requesting beets in mustard.

וְכַד הֲוָה שָׁאֵיל בְּאוּשְׁפִּיזָא, אָמַר הָכִי: גְּבַר פּוּם דֵּין חַי, מַה זּוֹ טוֹבָה יֵשׁ?

And when he would inquire about an inn, he would say as follows: This man here is raw; what is this good that there is? The phrase “this man here is raw” is used in a similar syllable-by-syllable translation: man in Hebrew is ish; here is po; this is zeh; and raw is na. All together, they sound like ushpazikhna, i.e., an innkeeper (Rabbeinu Ḥananel). In other words, Rabbi Yosei bar Asyan was asking after the innkeeper.

רַבִּי אֲבָהוּ כִּי הֲוָה מִשְׁתַּעֵי בִּלְשׁוֹן חׇכְמָה, הֲוָה אָמַר הָכִי: אַתְרִיגוּ לְפֶחָמִין, אַרְקִיעוּ לִזְהָבִין, וַעֲשׂוּ לִי שְׁנֵי מַגִּידֵי בַּעֲלָטָה. אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי: וְיַעֲשׂוּ לִי בָּהֶן שְׁנֵי מַגִּידֵי בַּעֲלָטָה.

When Rabbi Abbahu would speak enigmatically, he would say as follows: Make the coals the color of an etrog; beat the golden ones, i.e., spread out the coals, which redden like gold when they glow; and make me two speakers-in-the-dark, i.e., roosters, which announce the dawn when it is still dark. Some say a slightly different version: And they shall make me in them, on the coals, i.e., roast for me on top of the coals, two speakers-in-the-dark.

אֲמַרוּ לֵיהּ רַבָּנַן לְרַבִּי אֲבָהוּ: הַצְפִּינֵנוּ הֵיכָן רַבִּי אִלְעַאי צָפוּן. אָמַר לָהֶן: עָלַץ בְּנַעֲרָה אַהֲרוֹנִית אַחֲרוֹנִית עֵירָנִית וְהִנְעִירַתּוּ.

In a similarly clever manner, the Sages said to Rabbi Abbahu: Show us [hatzpinenu] where Rabbi Elai is hiding [tzafun], as we do not know his whereabouts. He said to them: He rejoiced with the latter [aḥaronit] Aharonic [Aharonit] girl; she is lively [eiranit] and kept him awake [vehiniratu].

אָמְרִי לַהּ אִשָּׁה.

There are two ways to understand this cryptic statement: Some say it refers to a woman, i.e., he married a young girl from a priestly family [Aharonic], who is his second [latter] wife, from a village [eiranit], and he is sleeping now because she kept him awake during the night.

וְאָמְרִי לַהּ מַסֶּכְתָּא.

And some say it refers to a tractate. The term girl refers to the tractate; Aharonic indicates that it is a tractate from the order of Kodashim, which deals with the priestly service. The phrase the latter means that it is his latest course of study, and lively alludes to the challenging nature of the subject matter. Since he was awake all night studying, he is presently sleeping.

אָמְרִי לֵיהּ לְרַבִּי אִלְעַאי: הַצְפִּינֵנוּ הֵיכָן רַבִּי אֲבָהוּ [צָפוּן]. אָמַר לָהֶן: נִתְיָיעֵץ בַּמַּכְתִּיר וְהִנְגִּיב לִמְפִיבֹשֶׁת.

The Gemara continues: They said to Rabbi Elai: Show us where Rabbi Abbahu is hiding, as we do not know where he is. He said to them: He has taken counsel with the one who crowns, i.e., the Nasi, who appoints the Sages, and has gone south [hingiv] to Mephibosheth, i.e., he has headed to the Sages of the south, referred to here as Mephibosheth, who was King Saul’s grandson and a great Sage of his time.

אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן חֲנַנְיָה: מִיָּמַי לֹא נִצְּחַנִי אָדָם חוּץ מֵאִשָּׁה תִּינוֹק וְתִינוֹקֶת. אִשָּׁה מַאי הִיא? פַּעַם אַחַת נִתְאָרַחְתִּי אֵצֶל אַכְסַנְיָא אַחַת, עָשְׂתָה לִי פּוֹלִין בְּיוֹם רִאשׁוֹן — אֲכַלְתִּים וְלֹא שִׁיַּירְתִּי מֵהֶן כְּלוּם. שְׁנִיָּיה, וְלֹא שִׁיַּירְתִּי מֵהֶן כְּלוּם. בְּיוֹם שְׁלִישִׁי הִקְדִּיחָתַן בְּמֶלַח, כֵּיוָן שֶׁטָּעַמְתִּי — מָשַׁכְתִּי יָדַי מֵהֶן.

Having discussed the clever speech of various Sages, the Gemara relates that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Ḥananya said as follows: In all my days, no person defeated me in a verbal encounter except for a woman, a young boy, and a young girl. What is the encounter in which a woman got the better of me? One time I was staying at a certain inn and the hostess prepared me beans. On the first day I ate them and left nothing over, although proper etiquette dictates that one should leave over something on his plate. On the second day I again ate and left nothing over. On the third day she over-salted them so that they were inedible. As soon as I tasted them, I withdrew my hands from them.

אָמְרָה לִי: רַבִּי, מִפְּנֵי מָה אֵינְךָ סוֹעֵד? אָמַרְתִּי לָהּ: כְּבָר סָעַדְתִּי מִבְּעוֹד יוֹם. אָמְרָה לִי: הָיָה לְךָ לִמְשׁוֹךְ יָדֶיךָ מִן הַפַּת!

She said to me: My Rabbi, why aren’t you eating beans as on the previous days? Not wishing to offend her, I said to her: I have already eaten during the daytime. She said to me: You should have withdrawn your hand from bread and left room for some beans.

אָמְרָה לִי: רַבִּי, שֶׁמָּא לֹא הִנַּחְתָּ פֵּאָה בָּרִאשׁוֹנִים? וְלֹא כָּךְ אָמְרוּ חֲכָמִים: אֵין מְשַׁיְּירִין פֵּאָה בָּאִלְפָּס, אֲבָל מְשַׁיְּירִין פֵּאָה בַּקְּעָרָה.

She then said to me: My Rabbi, perhaps you did not leave a remainder of food on your plate on the first days, which is why you are leaving over food today. Isn’t this what the Sages said: One need not leave a remainder in the pot [ilpas], but one must leave a remainder on the plate as an expression of etiquette (Tosafot). This is the incident in which a woman got the better of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Ḥananya.

תִּינוֹקֶת מַאי הִיא? פַּעַם אַחַת הָיִיתִי מְהַלֵּךְ בַּדֶּרֶךְ, וְהָיְתָה דֶּרֶךְ עוֹבֶרֶת בַּשָּׂדֶה, וְהָיִיתִי מְהַלֵּךְ בָּהּ. אָמְרָה לִי תִּינוֹקֶת אַחַת: רַבִּי, לֹא שָׂדֶה הִיא זוֹ? אָמַרְתִּי לָהּ: לֹא, דֶּרֶךְ כְּבוּשָׁה הִיא. אָמְרָה לִי: לִיסְטִים כְּמוֹתְךָ כְּבָשׁוּהָ.

What is the incident with a young girl? One time I was walking along the path, and the path passed through a field, and I was walking on it. A certain young girl said to me: My Rabbi, isn’t this a field? One should not walk through a field, so as not to damage the crops growing there. I said to her: Isn’t it a well-trodden path in the field, across which one is permitted to walk? She said to me: Robbers like you have trodden it. In other words, it previously had been prohibited to walk through this field, and it is only due to people such as you, who paid no attention to the prohibition, that a path has been cut across it. Thus, the young girl defeated Rabbi Yehoshua ben Ḥananya in a debate.

תִּינוֹק מַאי הִיא? פַּעַם אַחַת הָיִיתִי מְהַלֵּךְ בַּדֶּרֶךְ, וְרָאִיתִי תִּינוֹק יוֹשֵׁב עַל פָּרָשַׁת דְּרָכִים. וְאָמַרְתִּי לוֹ: בְּאֵיזֶה דֶּרֶךְ נֵלֵךְ לָעִיר? אָמַר לִי: זוֹ קְצָרָה וַאֲרוּכָּה, וְזוֹ אֲרוּכָּה וּקְצָרָה. וְהָלַכְתִּי בִּקְצָרָה וַאֲרוּכָּה, כֵּיוָן שֶׁהִגַּעְתִּי לָעִיר מָצָאתִי שֶׁמַּקִּיפִין אוֹתָהּ גַּנּוֹת וּפַרְדֵּיסִין.

What is the incident with a young boy? One time I was walking along the path, and I saw a young boy sitting at the crossroads. And I said to him: On which path shall we walk in order to get to the city? He said to me: This path is short and long, and that path is long and short. I walked on the path that was short and long. When I approached the city I found that gardens and orchards surrounded it, and I did not know the trails leading through them to the city.

חָזַרְתִּי לַאֲחוֹרַי. אָמַרְתִּי לוֹ: בְּנִי, הֲלֹא אָמַרְתָּ לִי קְצָרָה? אָמַר לִי: וְלֹא אָמַרְתִּי לְךָ אֲרוּכָּה? נְשַׁקְתִּיו עַל רֹאשׁוֹ, וְאָמַרְתִּי לוֹ: אַשְׁרֵיכֶם יִשְׂרָאֵל שֶׁכּוּלְּכֶם חֲכָמִים גְּדוֹלִים אַתֶּם, מִגְּדוֹלְכֶם וְעַד קְטַנְּכֶם.

I went back and met the young boy again and said to him: My son, didn’t you tell me that this way is short? He said to me: And didn’t I tell you that it is also long? I kissed him on his head and said to him: Happy are you, O Israel, for you are all exceedingly wise, from your old to your young.

רַבִּי יוֹסֵי הַגְּלִילִי הֲוָה קָא אָזֵיל בְּאוֹרְחָא, אַשְׁכְּחַהּ לִבְרוּרְיָה אֲמַר לַהּ: בְּאֵיזוֹ דֶּרֶךְ נֵלֵךְ לְלוֹד? אֲמַרָה לֵיהּ: גָּלִילִי שׁוֹטֶה, לֹא כָּךְ אָמְרוּ חֲכָמִים: אַל תַּרְבֶּה שִׂיחָה עִם הָאִשָּׁה?! הָיָה לְךָ לוֹמַר: ״בְּאֵיזֶה לְלוֹד״.

Having discussed wise speech and the wisdom of Jewish women, the Gemara cites the following story: Rabbi Yosei HaGelili was walking along the way, and met Berurya. He said to her: On which path shall we walk in order to get to Lod? She said to him: Foolish Galilean, didn’t the Sages say: Do not talk much with women? You should have said your question more succinctly: Which way to Lod?

בְּרוּרְיָה אַשְׁכַּחְתֵּיהּ לְהַהוּא תַּלְמִידָא דַּהֲוָה קָא גָרֵיס בִּלְחִישָׁה.

The Gemara relates more of Berurya’s wisdom: Berurya came across a certain student who was whispering his studies rather than raising his voice.