The gemara discusses what is considered part of the city and what is not considered part of the city regarding from where we would measure the techum. Straight lines are drawn from parts that protrude and if the shape of the inhabited part of the city is not square (i.e. round, rainbow-shaped, etc.) from where do we measure the 2,000 cubits?

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Today’s daily daf tools:

Today’s daily daf tools:

Delve Deeper

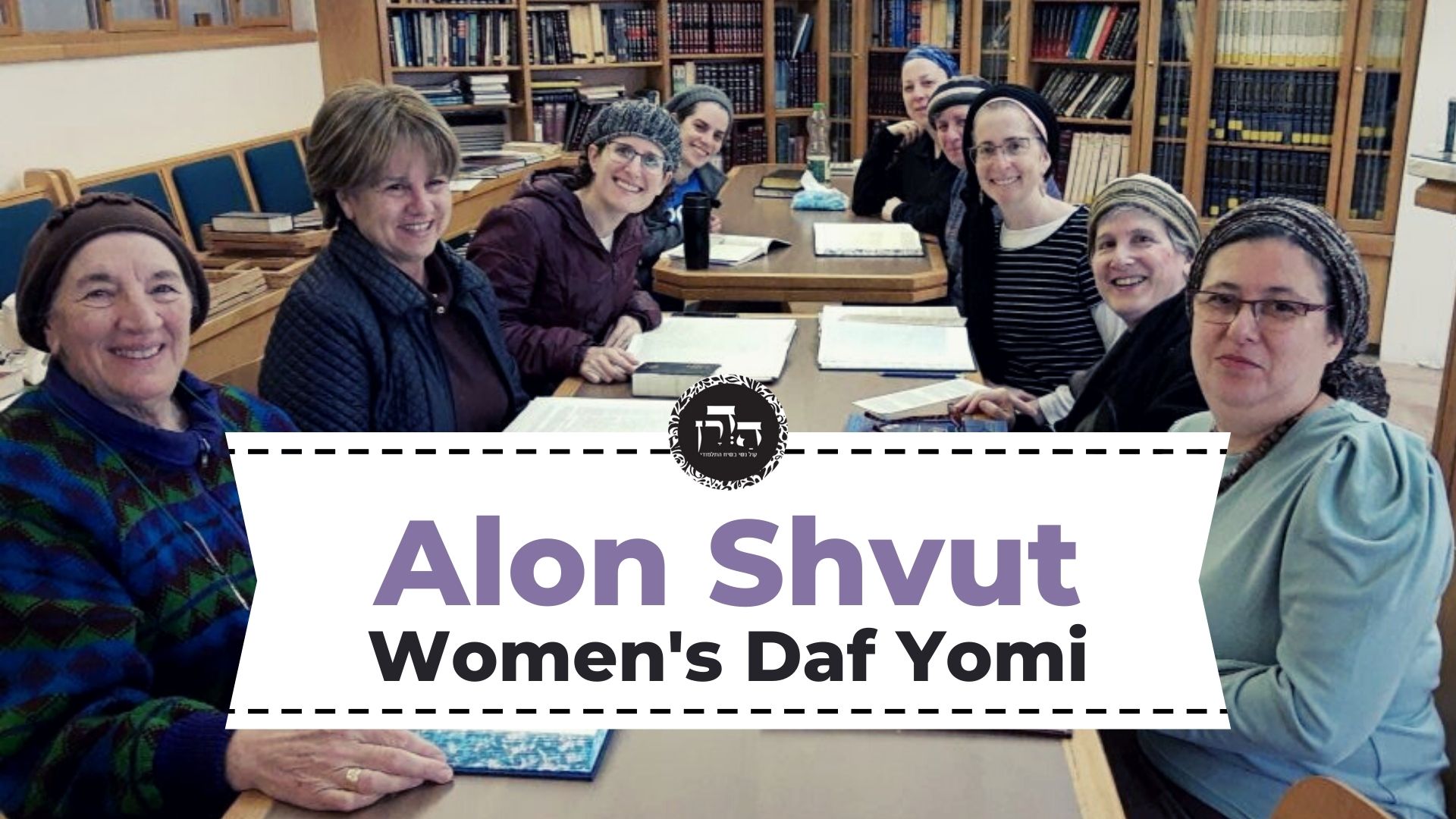

Broaden your understanding of the topics on this daf with classes and podcasts from top women Talmud scholars.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Eruvin 55

וְהַיְינוּ דְּאָמַר אַבְדִּימִי בַּר חָמָא בַּר דּוֹסָא, מַאי דִּכְתִיב: ״לֹא בַשָּׁמַיִם הִיא וְלֹא מֵעֵבֶר לַיָּם הִיא״. ״לָא בַּשָּׁמַיִם הִיא״, שֶׁאִם בַּשָּׁמַיִם הִיא — אַתָּה צָרִיךְ לַעֲלוֹת אַחֲרֶיהָ, וְאִם מֵעֵבֶר לַיָּם הִיא — אַתָּה צָרִיךְ לַעֲבוֹר אַחֲרֶיהָ.

And this idea, that one must exert great effort to retain one’s Torah knowledge, is in accordance with what Avdimi bar Ḥama bar Dosa said: What is the meaning of that which is written: “It is not in heaven…nor is it beyond the sea” (Deuteronomy 30:12–13)? “It is not in heaven” indicates that if it were in heaven, you would have to ascend after it, and if it were beyond the sea, you would have to cross after it, as one must expend whatever effort is necessary in order to study Torah.

רָבָא אָמַר: ״לֹא בַשָּׁמַיִם הִיא״ — לֹא תִּמָּצֵא בְּמִי שֶׁמַּגְבִּיהַּ דַּעְתּוֹ עָלֶיהָ כַּשָּׁמַיִם, וְלֹא תִּמָּצֵא בְּמִי שֶׁמַּרְחִיב דַּעְתּוֹ עָלֶיהָ כַּיָּם.

Expounding the verse differently, Rava said: “It is not in heaven” means that Torah is not to be found in someone who raises his mind over it, like the heavens, i.e., he thinks his mind is above the Torah and he does not need a teacher; nor is it to be found in someone who expands his mind over it, like the sea, i.e., he thinks he knows everything there is to know about the topic he has learned.

רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר: ״לֹא בַּשָּׁמַיִם הִיא״ — לֹא תִּמָּצֵא בְּגַסַּי רוּחַ, ״וְלֹא מֵעֵבֶר לַיָּם הִיא״ — לֹא תִּמָּצֵא לֹא בְּסַחְרָנִים וְלֹא בְּתַגָּרִים.

Rabbi Yoḥanan said: “It is not in heaven” means that Torah is not to be found in the haughty, those who raise their self-image as though they were in heaven. “Nor is it beyond the sea” means that it is not to be found among merchants or traders who are constantly traveling and do not have the time to study Torah properly.

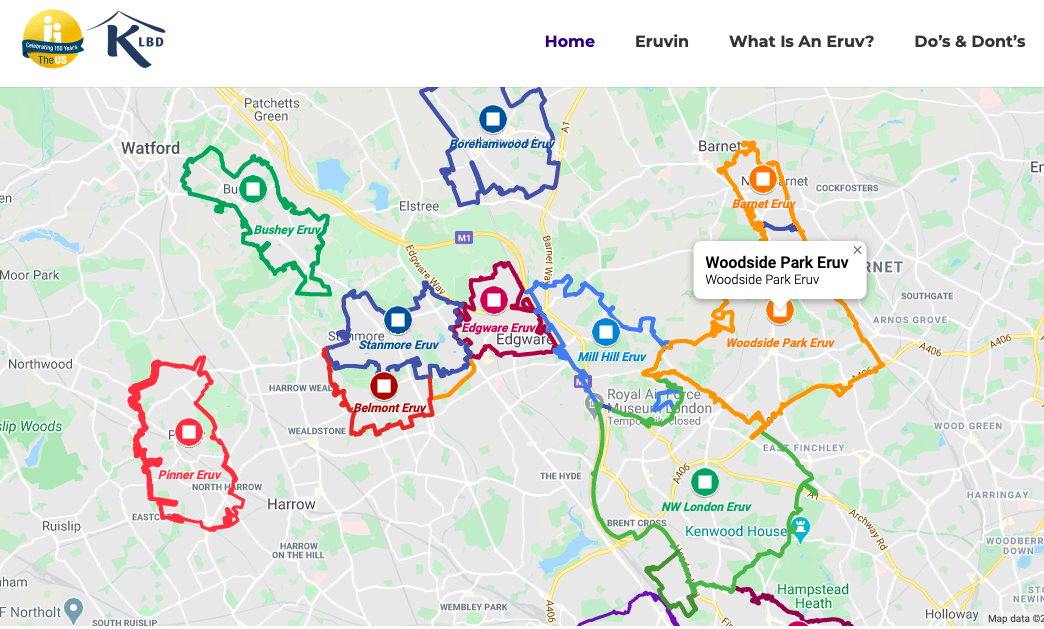

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: כֵּיצַד מְעַבְּרִין אֶת הֶעָרִים? אֲרוּכָּה — כְּמוֹת שֶׁהִיא. עֲגוּלָּה — עוֹשִׂין לָהּ זָוִיּוֹת. מְרוּבַּעַת — אֵין עוֹשִׂין לָהּ זָוִיּוֹת. הָיְתָה רְחָבָה מִצַּד אֶחָד וּקְצָרָה מִצַּד אַחֵר — רוֹאִין אוֹתָהּ כְּאִילּוּ הִיא שָׁוָה.

After the lengthy aggadic digression, the Gemara returns to the topic of the mishna, extending the outskirts of a city. The Sages taught in the Tosefta: How does one extend the boundaries of cities? If the city is long, in the shape of a rectangle, the Shabbat limit is measured from the boundary as it is. If the city is round, one creates simulated corners for it, rendering it square, and the Shabbat limit is measured from there. If it is square, one does not create additional corners for it. If the city was wide on one side and narrow on the other side, one regards it as though the two sides were of equal length, adding to the narrow side to form a square.

הָיָה בַּיִת אֶחָד יוֹצֵא כְּמִין פִּגּוּם, אוֹ שְׁנֵי בָתִּים יוֹצְאִין כְּמִין שְׁנֵי פִגּוּמִין — רוֹאִין אוֹתָן כְּאִילּוּ חוּט מָתוּחַ עֲלֵיהֶן, וּמוֹדֵד מִמֶּנּוּ וּלְהַלָּן אַלְפַּיִם אַמָּה. הָיְתָה עֲשׂוּיָה כְּמִין קֶשֶׁת אוֹ כְּמִין גַּאם — רוֹאִין אוֹתָהּ כְּאִילּוּ הִיא מְלֵאָה בָּתִּים וַחֲצֵירוֹת, וּמוֹדֵד מִמֶּנּוּ וּלְהַלָּן אַלְפַּיִם אַמָּה.

If one house in a row of dwellings was protruding like a turret, or if two houses were protruding like two turrets, one regards them as though a cord is stretched over their outer edge along the length of the city, and one measures two thousand cubits beginning from there. If the city was shaped like a bow or like the Greek letter gamma, one regards it as though the interior space were full of houses and courtyards, and one measures two thousand cubits beginning from there.

אָמַר מָר: אֲרוּכָּה כְּמוֹת שֶׁהִיא. פְּשִׁיטָא! לָא צְרִיכָא, דַּאֲרִיכָא וְקַטִּינָא, מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: לִיתֵּן לַהּ פּוּתְיָא אַאוּרְכַּהּ. קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara proceeds to analyze the Tosefta. The Master said: If the city is long, the Shabbat limit is measured from the boundary as it is. The Gemara expresses surprise: That is obvious. The Gemara explains: It was necessary to teach this halakha only with regard to a case where the city is long and narrow. Lest you say: Let us give its breadth the dimension of its length and regard the city as if it were square, it teaches us that we do not do so.

מְרוּבַּעַת אֵין עוֹשִׂין לָהּ זָוִיּוֹת. פְּשִׁיטָא! לָא צְרִיכָא, דִּמְרַבְּעָא, וְלָא מְרַבְּעָא בְּרִיבּוּעַ עוֹלָם. מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: לִירַבְּעָא בְּרִיבּוּעַ עוֹלָם. קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Tosefta stated: If the city is square, one does not create additional corners for it. Once again the Gemara asks: That is obvious. The Gemara answers: It was necessary to teach this halakha only with regard to a case where the shape of the city is square but that square is not aligned with the four directions of the world, i.e., north, south, east, and west. Lest you say: Let us align the square with the four directions of the world, it teaches us that this is not done.

הָיָה בַּיִת אֶחָד יוֹצֵא כְּמִין פִּגּוּם אוֹ שְׁנֵי בָתִּים יוֹצְאִין כְּמִין שְׁנֵי פִגּוּמִין. הַשְׁתָּא בַּיִת אֶחָד אָמְרַתְּ, שְׁנֵי בָתִּים מִיבַּעְיָא?!

The Tosefta also stated: If one house in a row of dwellings was protruding like a turret, or if two houses were protruding like two turrets, one regards them as though a cord is stretched over their outer edge along the length of the city, and one measures two thousand cubits beginning from there. The Gemara asks: Now, if with regard to one house, you said to extend the city’s boundaries, with regard to two houses, is it necessary to say so?

לָא צְרִיכָא, מִשְׁתֵּי רוּחוֹת. מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: מֵרוּחַ אַחַת אָמְרִינַן, מִשְׁתֵּי רוּחוֹת לָא אָמְרִינַן. קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara answers: It was necessary to teach this halakha only with regard to a case where the two houses were protruding on two different sides of the city. Lest you say: When a house protrudes from one side, we say that the city is extended even due to a single house, but if houses protrude from two sides we do not say so; therefore, it teaches us to regard the city as though it is extended on both sides.

הָיְתָה עֲשׂוּיָה כְּמִין קֶשֶׁת אוֹ כְּמִין גַּאם, רוֹאִין אוֹתָהּ כְּאִילּוּ הִיא מְלֵאָה בָתִּים וַחֲצֵירוֹת, וּמוֹדֵד מִמֶּנָּה וּלְהַלָּן אַלְפַּיִם אַמָּה. אָמַר רַב הוּנָא: עִיר הָעֲשׂוּיָה כְּקֶשֶׁת, אִם יֵשׁ בֵּין שְׁנֵי רָאשֶׁיהָ פָּחוֹת מֵאַרְבַּעַת אֲלָפִים אַמָּה — מוֹדְדִין לָהּ מִן הַיֶּתֶר, וְאִם לָאו — מוֹדְדִין לָהּ מִן הַקֶּשֶׁת.

The Tosefta stated: If the city was shaped like a bow or like the Greek letter gamma, one regards it as if the interior space were full of houses and courtyards, and one measures two thousand cubits beginning from there. Rav Huna said: With regard to a city that is shaped like a bow, the following distinction applies: If there are less than four thousand cubits between the two ends of the bow, so that the Shabbat limits measured from the two ends of the city overlap, the interior space of the bow is regarded as if it were filled with houses, and one measures the Shabbat limit of the city from the imaginary bowstring stretched between the two ends of the bow. But if that is not the case, and the distance between the two ends of the bow is four thousand cubits or more, one measures the Shabbat limit from the bow itself.

וּמִי אָמַר רַב הוּנָא הָכִי, וְהָאָמַר רַב הוּנָא: חוֹמַת הָעִיר שֶׁנִּפְרְצָה — בְּמֵאָה וְאַרְבָּעִים וְאַחַת וּשְׁלִישׁ?

The Gemara asks: Did Rav Huna actually say that the distance between two sections of a single city that renders them separate entities is four thousand cubits? Didn’t Rav Huna say: With regard to the wall of a city that was breached, even if there is a gap between two sections of the city, the city is still considered a single entity if the breach is no more than 141⅓ cubits? However, if the breach is wider, the two sections are considered separate entities. Apparently, a distance of 141⅓ cubits suffices to separate between two sections of a city and to render them separate entities.

אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר עוּלָּא, לָא קַשְׁיָא: כָּאן — בְּרוּחַ אַחַת, כָּאן — מִשְׁתֵּי רוּחוֹת.

Rabba bar Ulla said: That is not difficult. Here, where Rav Huna speaks of four thousand cubits, he is referring to a case where the gap is on only one side, as the other side, the bow, is inhabited; but there, where he speaks of 141⅓ cubits, he is referring to a case where the breach is from two sides, which truly renders the city two separate entities.

וּמַאי קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן? דְּנוֹתְנִין קַרְפֵּף לָזוֹ וְקַרְפֵּף לָזוֹ? הָא אַמְרַהּ רַב הוּנָא חֲדָא זִימְנָא, דִּתְנַן:

The Gemara asks: If so, what is Rav Huna teaching us in the case of the breached city wall, that one allocates a karpef, an area measuring slightly more than seventy cubits, to this section of the city and a karpef to that section of the city? Didn’t Rav Huna already say this on one occasion? As we learned in a mishna:

נוֹתְנִין קַרְפֵּף לָעִיר, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי מֵאִיר. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: לֹא אָמְרוּ קַרְפֵּף אֶלָּא בֵּין שְׁתֵּי עֲיָירוֹת.

One allocates a karpef to every city, i.e., an area of slightly more than seventy cubits is added to the boundary of a city and the Shabbat limit is measured from there; this is the statement of Rabbi Meir. And the Sages say: They spoke of the measure of a karpef only with regard to the space between two adjacent cities, i.e., if adjacent cities are separated by a shorter distance than that, they are considered one city.

וְאִיתְּמַר, רַב הוּנָא אָמַר: קַרְפֵּף לָזוֹ וְקַרְפֵּף לָזוֹ. וְחִיָּיא בַּר רַב אָמַר: אֵין נוֹתְנִין אֶלָּא קַרְפֵּף אֶחָד לִשְׁנֵיהֶם!

And it was stated that the amora’im disputed this issue. Rav Huna said: A karpef is added to this city and another karpef is added to that city, so that as long as the cities are not separated by a distance of slightly more than 141 cubits, they are considered one entity. And Ḥiyya bar Rav said: One allocates only one karpef to the two of them. Accordingly, Rav Huna has already stated that the measure of a karpef is added to both cities in determining whether they are close enough to be considered a single entity.

צְרִיכָא, דְּאִי אַשְׁמְעִינַן הָכָא — מִשּׁוּם דַּהֲוָה לֵיהּ צַד הֶיתֵּר מֵעִיקָּרָא. אֲבָל הָתָם, אֵימָא לָא.

The Gemara answers: It is necessary for Rav Huna to state this halakha in both instances, as, had he taught it to us only here, in the case of the breached wall, one might have said that a karpef is allocated to each city only in that case because it had an aspect of permissibility from the outset, namely, the two sections originally formed one city. But there, with regard to the two cities, say that this is not the case and the two cities are only considered as one if they are separated by less than the measure of a single karpef.

וְאִי אַשְׁמְעִינַן הָתָם — מִשּׁוּם דִּדְחִיקָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתַּיְיהוּ, אֲבָל הָכָא דְּלָא דְּחִיקָא תַּשְׁמִישְׁתַּיְיהוּ — אֵימָא לָא, צְרִיכָא.

And had he taught it to us only there, with regard to the two cities, one might have said that only in that case is a karpef allocated to each city because one karpef would be too cramped for the use of both cities. But here, in the case of the breached wall, where one karpef would not be too cramped for the use of both sections, as the vacant space is inside the city, in an area that had not been used in this fashion before the wall was breached, say that this is not the case and a single karpef is sufficient. Therefore, it was necessary to state this halakha in both cases.

וְכַמָּה הָוֵי בֵּין יֶתֶר לַקֶּשֶׁת? רַבָּה בַּר רַב הוּנָא אָמַר: אַלְפַּיִם אַמָּה, רָבָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַבָּה בַּר רַב הוּנָא אָמַר: אֲפִילּוּ יָתֵר מֵאַלְפַּיִם אַמָּה.

The Gemara asks: And how much distance may there be between the imaginary bowstring and the center of the bow in a city that is shaped like a bow? Rabba bar Rav Huna said: Two thousand cubits. Rava, son of Rabba bar Rav Huna, said: Even more than two thousand cubits.

אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּרָבָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַבָּה בַּר רַב הוּנָא מִסְתַּבְּרָא, דְּאִי בָּעֵי הָדַר אָתֵי דֶּרֶךְ בָּתִּים.

Abaye said: It stands to reason in accordance with the opinion of Rava, son of Rabba bar Rav Huna, as if one wants, he can return and go anywhere within the bow by way of the houses. Since one can always walk to the end of the city, and from there he is permitted to walk down the line of the imaginary bowstring, he should also be permitted to walk from the middle of the bow to the bowstring, even if the distance is more than two thousand cubits.

הָיוּ שָׁם גְּדוּדִיּוֹת גְּבוֹהוֹת עֲשָׂרָה טְפָחִים כּוּ׳. מַאי גְּדוּדִיּוֹת? אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה: שָׁלֹשׁ מְחִיצּוֹת שֶׁאֵין עֲלֵיהֶן תִּקְרָה.

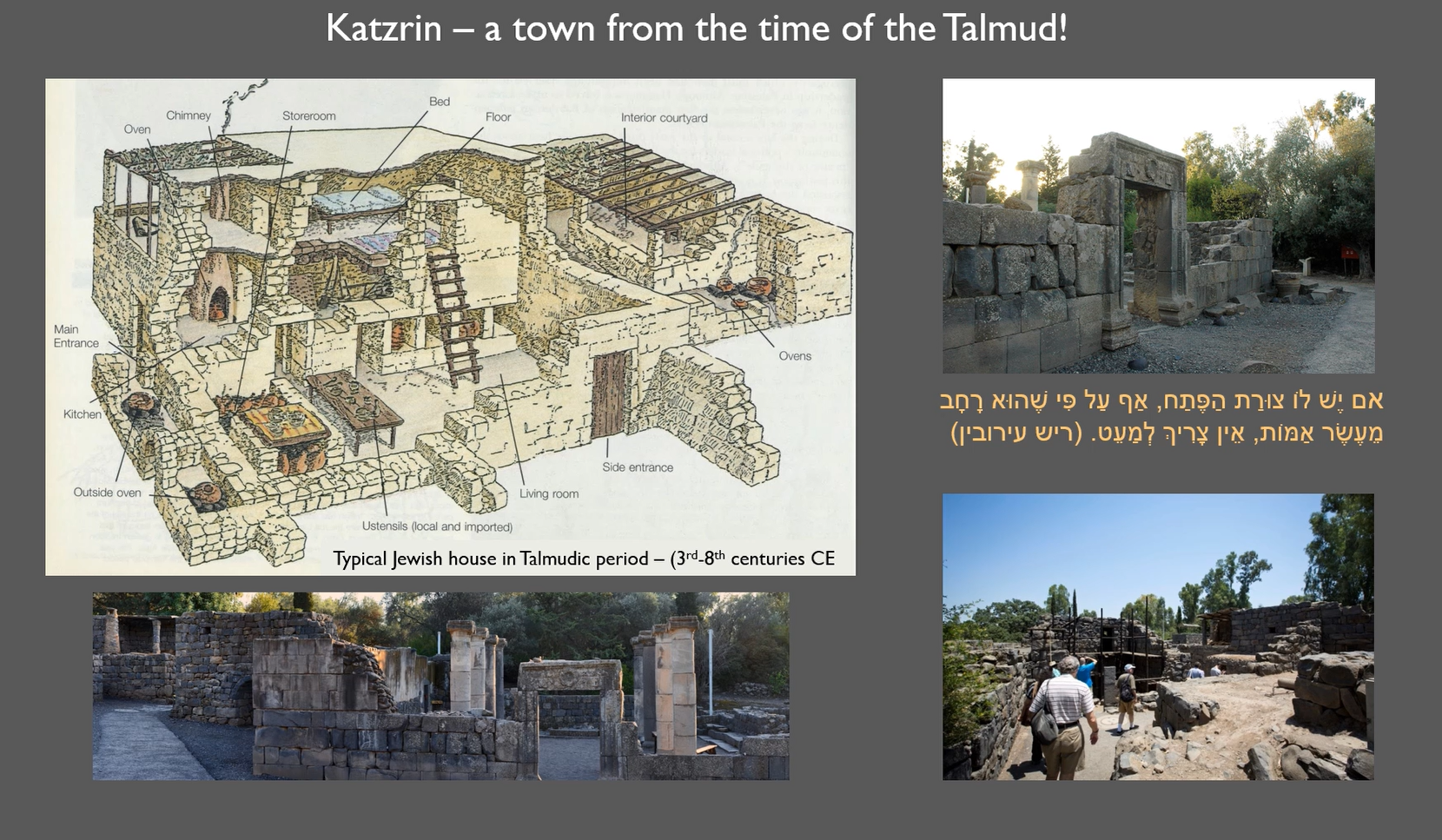

We learned in the mishna: If there were remnants of walls ten handbreadths high on the outskirts of a city, they are considered part of the city, and the Shabbat limit is measured from them. The Gemara asks: What are these remnants? Rav Yehuda said: Three partitions that do not have a roof over them, which are considered part of the city despite the fact that they do not comprise a proper house.

אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: שְׁתֵּי מְחִיצּוֹת וְיֵשׁ עֲלֵיהֶן תִּקְרָה, מַהוּ? תָּא שְׁמַע, אֵלּוּ שֶׁמִּתְעַבְּרִין עִמָּהּ: נֶפֶשׁ שֶׁיֵּשׁ בָּהּ אַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת עַל אַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת, וְהַגֶּשֶׁר וְהַקֶּבֶר שֶׁיֵּשׁ בָּהֶן בֵּית דִּירָה, וּבֵית הַכְּנֶסֶת שֶׁיֵּשׁ בָּהּ בֵּית דִּירָה לַחַזָּן, וּבֵית עֲבוֹדָה זָרָה שֶׁיֵּשׁ בָּהּ בֵּית דִּירָה לַכּוֹמָרִים, וְהָאוּרְווֹת וְהָאוֹצָרוֹת שֶׁבַּשָּׂדוֹת וְיֵשׁ בָּהֶן בֵּית דִּירָה, וְהַבּוּרְגָּנִין שֶׁבְּתוֹכָהּ, וְהַבַּיִת שֶׁבַּיָּם — הֲרֵי אֵלּוּ מִתְעַבְּרִין עִמָּהּ.

The dilemma was raised before the Sages: In the case of two partitions that have a roof over them, what is the halakha? Is this structure also treated like a house? Come and hear a proof from the Tosefta: These are the structures that are included in the city’s extension: A monument [nefesh] over a grave that is four cubits by four cubits; and a bridge or a grave in which there is a residence; and a synagogue in which there is a residence for the sexton or synagogue attendant, and which is used not only for prayer services at specific times; and an idolatrous temple in which there is a residence for the priests; and similarly, horse stables and storehouses in the fields in which there is a residence; and small watchtowers in the fields; and similarly, a house on an island in the sea or lake, which is located within seventy cubits of the city; all of these structures are included in the city’s boundaries.

וְאֵלּוּ שֶׁאֵין מִתְעַבְּרִין עִמָּהּ: נֶפֶשׁ שֶׁנִּפְרְצָה מִשְׁתֵּי רוּחוֹתֶיהָ אֵילָךְ וְאֵילָךְ, וְהַגֶּשֶׁר וְהַקֶּבֶר שֶׁאֵין לָהֶן בֵּית דִּירָה, וּבֵית הַכְּנֶסֶת שֶׁאֵין לָהּ בֵּית דִּירָה לַחַזָּן, וּבֵית עֲבוֹדָה זָרָה שֶׁאֵין לָהּ בֵּית דִּירָה לַכּוֹמָרִים, וְהָאוּרְווֹת וְהָאוֹצָרוֹת שֶׁבַּשָּׂדוֹת שֶׁאֵין לָהֶן בֵּית דִּירָה, וּבוֹר וְשִׁיחַ וּמְעָרָה וְגָדֵר וְשׁוֹבָךְ שֶׁבְּתוֹכָהּ, וְהַבַּיִת שֶׁבַּסְּפִינָה — אֵין אֵלּוּ מִתְעַבְּרִין עִמָּהּ.

And these structures are not included in the boundaries of a city: A tomb that was breached on both sides, from here to there, i.e., from one side all the way to the other; and similarly, a bridge and a grave that do not have a residence; and a synagogue that does not have a residence for the sexton; and an idolatrous temple that does not have a residence for the priests; and similarly, stables and storehouses in fields that do not have a residence, and therefore are not used for human habitation; and a cistern, and an elongated water ditch, and a cave, i.e., a covered cistern, and a wall, and a dovecote in the field; and similarly, a house on a boat that is not permanently located within seventy cubits of the city; all of these structures are not included in the city’s boundaries.

קָתָנֵי מִיהַת: נֶפֶשׁ שֶׁנִּפְרְצָה מִשְׁתֵּי רוּחוֹתֶיהָ אֵילָךְ וְאֵילָךְ. מַאי לָאו דְּאִיכָּא תִּקְרָה! לָא — דְּלֵיכָּא תִּקְרָה.

In any case, it was taught that a tomb that was breached on both sides, from here to there, is not included in the city’s boundaries. What, is this not referring to a case where there is a roof on the tomb, and the two remaining walls are not included in the city’s boundaries even though they have a roof? The Gemara answers: No, the Tosefta is referring to a case where there is no roof on the tomb.

בַּיִת שֶׁבַּיָּם. לְמַאי חֲזֵי? אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא: בַּיִת שֶׁעָשׂוּי לְפַנּוֹת בּוֹ כֵּלִים שֶׁבַּסְּפִינָה.

The Gemara asks: A house on an island in the sea, what is it suitable for if it is not actually part of the inhabited area? Rav Pappa said: It is referring to a house used to move a ship’s utensils into it for storage.

וּמְעָרָה אֵין מִתְעַבֶּרֶת עִמָּהּ, וְהָתָנֵי רַבִּי חִיָּיא: מְעָרָה מִתְעַבֶּרֶת עִמָּהּ! אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: כְּשֶׁיֵּשׁ בִּנְיָן עַל פִּיהָ.

The Gemara raises another question with regard to the Tosefta: And is a cave on the outskirts of a city really not included in its extension? Didn’t Rabbi Ḥiyya teach in a baraita: A cave is included in its extension? Abaye said: That statement applies when there is a structure built at its entrance, which is treated like a house on the outskirts of the city.

וְתִיפּוֹק לֵיהּ מִשּׁוּם בִּנְיָן גּוּפֵיהּ! לָא צְרִיכָא, לְהַשְׁלִים.

The Gemara asks: If there is a structure at the entrance to the cave, why is the cave mentioned? Let him derive the halakha that it is treated like a house because of the structure itself. The Gemara answers: No, it is necessary only in a case where the cave serves to complete the structure, i.e., where the area of the structure and cave combined are only four by four cubits, which is the minimum size of a house.

אָמַר רַב הוּנָא: יוֹשְׁבֵי צְרִיפִין, אֵין מוֹדְדִין לָהֶן אֶלָּא מִפֶּתַח בָּתֵּיהֶן.

The discussion with regard to measuring Shabbat limits has been referring to a properly built city. Rav Huna said: Those who dwell in huts, i.e., in thatched hovels of straw and willow branches, are not considered inhabitants of a city. Therefore, one measures the Shabbat limit for them only from the entrance to their homes; the huts are not combined together and considered a city.

מֵתִיב רַב חִסְדָּא: ״וַיַּחֲנוּ עַל הַיַּרְדֵּן מִבֵּית הַיְשִׁימוֹת״, וְאָמַר רַבָּה בַּר בַּר חָנָה (אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן): לְדִידִי חֲזֵי לִי הָהוּא אַתְרָא, וְהָוֵי תְּלָתָא פַּרְסֵי עַל תְּלָתָא פַּרְסֵי.

Rav Ḥisda raised an objection: The Torah states with regard to the Jewish people in the desert: “And they pitched by the Jordan, from Beit-HaYeshimot to Avel-Shittim in the plains of Moab” (Numbers 33:49), and Rabba bar bar Ḥana said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: I myself saw that place, and it is three parasangs [parsa], the equivalent of twelve mil, by three parasangs.

וְתַנְיָא: כְּשֶׁהֵן נִפְנִין — אֵין נִפְנִין לֹא לִפְנֵיהֶם, וְלֹא לְצִדֵּיהֶן, אֶלָּא לְאַחֲרֵיהֶן?

And it was taught in a baraita: When they would defecate in the wilderness, they would not defecate in front of themselves, i.e., in front of the camp, and not to their sides, due to respect for the Divine Presence; rather, they would do so behind the camp. This indicates that even on Shabbat, when people needed to defecate, they would walk the entire length of the camp, which was considerably longer than two thousand cubits, which equals one mil. It is apparent that the encampment of the Jewish people was considered to be a city despite the fact that it was composed of tents alone. How, then, did Rav Huna say that those who live in huts are not considered city dwellers?

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא: דִּגְלֵי מִדְבָּר קָאָמְרַתְּ? כֵּיוָן דִּכְתִיב בְּהוּ: ״עַל פִּי ה׳ יַחֲנוּ וְעַל פִּי ה׳ יִסָּעוּ״ — כְּמַאן דִּקְבִיעַ לְהוּ דָּמֵי.

Rava said to him: The banners of the desert, you say? Are you citing a proof from the practice of the Jewish people as they traveled through the desert according to their tribal banners? Since it is written with regard to them: “According to the commandment of the Lord they remained encamped, and according to the commandment of the Lord they journeyed” (Numbers 9:20), it was considered as though it were a permanent residence for them. A camp that is established in accordance with the word of God is regarded as a permanent settlement.

אָמַר רַב חִינָּנָא בַּר רַב כָּהֲנָא אָמַר רַב אָשֵׁי: אִם יֵשׁ שָׁם שָׁלֹשׁ חֲצֵירוֹת שֶׁל שְׁנֵי בָתִּים — הוּקְבְּעוּ.

Rav Ḥinnana bar Rav Kahana said that Rav Ashi said: If there are three courtyards of two properly built houses among a settlement of huts, they have been established as a permanent settlement, and the Shabbat limit is measured from the edge of the settlement.

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב: יוֹשְׁבֵי צְרִיפִין וְהוֹלְכֵי מִדְבָּרוֹת — חַיֵּיהֶן אֵינָן חַיִּים, וּנְשֵׁיהֶן וּבְנֵיהֶן אֵינָן שֶׁלָּהֶן.

On the topic of people who dwell in huts, Rav Yehuda said that Rav said: Those who dwell in huts, such as shepherds who pass from one place to another and stay in a single location for only a brief period, and desert travelers, their lives are not lives, i.e., they lead extremely difficult lives, and their wives and children are not always their own, as will be explained below.

תַּנְיָא נָמֵי הָכִי, אֱלִיעֶזֶר אִישׁ בִּירְיָא אוֹמֵר: יוֹשְׁבֵי צְרִיפִין כְּיוֹשְׁבֵי קְבָרִים. וְעַל בְּנוֹתֵיהֶם הוּא אוֹמֵר: ״אָרוּר שׁוֹכֵב עִם כׇּל בְּהֵמָה״.

That was also taught in the following baraita: Eliezer of Biriyya says: Those who dwell in huts are like those who dwell in graves. And with regard to one who marries their daughters, the verse says: “Cursed be he who sleeps with any manner of beast” (Deuteronomy 27:21).

מַאי טַעְמָא? עוּלָּא אָמַר: שֶׁאֵין לָהֶן מֶרְחֲצָאוֹת. וְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר: מִפְּנֵי שֶׁמַּרְגִּישִׁין זֶה לָזֶה בִּטְבִילָה.

The Gemara asks: What is the reason for this harsh statement with regard to the daughters of those who dwell in huts or travel in deserts? Ulla said: They do not have bathhouses, and therefore the men have to walk a significant distance in order to bathe. There is concern that while they are away their wives commit adultery, and that consequently their children are not really their own. And Rabbi Yoḥanan said: Because they sense when one another immerses. Similarly to the men, the women must walk a significant distance in order to immerse in a ritual bath. Since the settlement is very small and everyone knows when the women go to immerse, it is possible for an unscrupulous man to use this information to engage in adulterous relations with them by following them and taking advantage of the fact that they are alone.

מַאי בֵּינַיְיהוּ? אִיכָּא בֵּינַיְיהוּ נַהֲרָא דִּסְמִיךְ לְבֵיתָא.

The Gemara asks: What is the practical difference between the explanations of Ulla and Rabbi Yoḥanan? The Gemara explains: There is a practical difference between them in a case where there is a river that is adjacent to the house, and it is suitable for immersion but not for bathing. Consequently, the women would not have to go far to immerse themselves, but the men would still have to walk a significant distance in order to bathe.

אָמַר רַב הוּנָא: כׇּל עִיר שֶׁאֵין בָּהּ יָרָק — אֵין תַּלְמִיד חָכָם רַשַּׁאי לָדוּר בָּהּ. לְמֵימְרָא דְּיָרָק מְעַלְּיָא? וְהָתַנְיָא: שְׁלֹשָׁה מַרְבִּין אֶת הַזֶּבֶל, וְכוֹפְפִין אֶת הַקּוֹמָה, וְנוֹטְלִין אֶחָד מֵחֲמֵשׁ מֵאוֹת מִמְּאוֹר עֵינָיו שֶׁל אָדָם, וְאֵלּוּ הֵן:

Having mentioned various places of residence, the Gemara cites what Rav Huna said: Any city that does not have vegetables, a Torah scholar is not permitted to dwell there for health reasons. The Gemara asks: Is that to say that vegetables are beneficial to a person’s health? Wasn’t it taught in a baraita: Three things increase one’s waste, bend his stature, and remove one five-hundredth of the light of a person’s eyes; and they are