Yevamot 108

אָתֵי לְאִיחַלּוֹפֵי בְּגִיטָּא. תַּקִּינוּ הָכִי: ״בְּיוֹם פְּלוֹנִי מֵיאֲנָה פְּלוֹנִית בַּת פְּלוֹנִי בְּאַנְפַּנָא״.

This document may come to be confused with a bill of divorce and perhaps a man will err and give a bill of divorce using the text of refusal. Therefore, they decreed that one should write as follows: On such and such a day, so-and-so, the daughter of so-and-so, performed refusal in our presence, and no more.

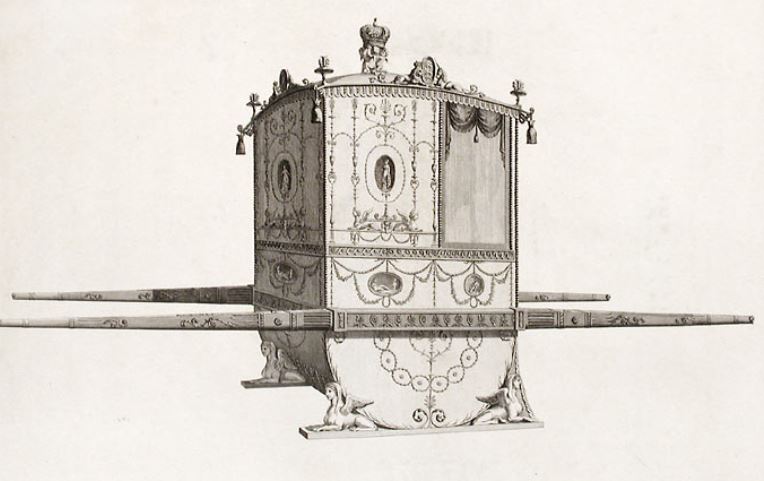

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: אֵי זֶהוּ מֵיאוּן? אָמְרָה: ״אִי אֶפְשִׁי בִּפְלוֹנִי בַּעְלִי״, ״אִי אֶפְשִׁי בְּקִידּוּשִׁין שֶׁקִּידְּשׁוּנִי אִמִּי וְאַחַי״. יָתֵר עַל כֵּן אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: אֲפִילּוּ יוֹשֶׁבֶת בְּאַפִּרְיוֹן וְהוֹלֶכֶת מִבֵּית אָבִיהָ לְבֵית בַּעְלָהּ, וְאָמְרָה: ״אִי אֶפְשִׁי בִּפְלוֹנִי בַּעְלִי״ — זֶהוּ מֵיאוּן.

§ The Sages taught: What constitutes a refusal? If she said: I do not want so-and-so as my husband, or: I do not want the betrothal in which my mother and brothers had me betrothed, that is a refusal. Rabbi Yehuda said more than that: Even if she is sitting in a bridal chair [apiryon] going from her father’s house to her husband’s house and said along the way: I do not want so-and-so as my husband, this constitutes a refusal.

יָתֵר עַל כֵּן אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: אֲפִילּוּ הָיוּ אוֹרְחִין מְסוּבִּין בְּבֵית בַּעְלָהּ וְהִיא עוֹמֶדֶת וּמַשְׁקָה עֲלֵיהֶם, וְאָמְרָה לָהֶם: ״אִי אֶפְשִׁי בִּפְלוֹנִי בַּעְלִי״ — הֲרֵי הוּא מֵיאוּן. יָתֵר עַל כֵּן אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר יְהוּדָה: אֲפִילּוּ שִׁיגְּרָהּ בַּעְלָהּ אֵצֶל חֶנְוָנִי לְהָבִיא לוֹ חֵפֶץ מִשֶּׁלּוֹ, וְאָמְרָה: ״אִי אֶפְשִׁי בִּפְלוֹנִי בַּעְלִי״ — אֵין לְךָ מֵיאוּן גָּדוֹל מִזֶּה.

Rabbi Yehuda said even more than that: Even if guests are reclining at her husband’s house and she is standing and serving them drinks as hostess, and she said to them: I do not want so-and-so as my husband, this constitutes a refusal, even though it is possible that she is merely complaining about the effort she is expending. Rabbi Yosei bar Yehuda said more than that: Even if her husband sent her to a shopkeeper to bring him an article of his and she said: I do not want so-and-so as my husband, there is no greater refusal than this.

רַבִּי חֲנִינָא בֶּן אַנְטִיגְנוֹס אוֹמֵר: כׇּל תִּינוֹקֶת וְכוּ׳. אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי חֲנִינָא בֶּן אַנְטִיגְנוֹס. תָּנָא: קְטַנָּה שֶׁלֹּא מֵיאֲנָה, וְעָמְדָה וְנִשֵּׂאת, מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי יְהוּדָה בֶּן בְּתִירָה אָמְרוּ: נִישּׂוּאֶיהָ הֵן הֵן מֵיאוּנֶיהָ.

§ It was taught in the mishna: Rabbi Ḥanina ben Antigonus says: Any girl who is so young that she cannot keep her betrothal safe does not need to refuse. Rav Yehuda said that Shmuel said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Ḥanina ben Antigonus. It was taught: In the case of a minor girl who did not refuse her husband, but who went and married someone else, it was said in the name of Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira: Her new marriage constitutes her refusal, as she made her state of mind known, that she does not want him, and that is sufficient.

אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: נִתְקַדְּשָׁה, מַהוּ? תָּא שְׁמַע: קְטַנָּה שֶׁלֹּא מֵיאֲנָה וְעָמְדָה וְנִתְקַדְּשָׁה — מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי יְהוּדָה בֶּן בְּתִירָה אָמְרוּ: קִידּוּשֶׁיהָ הֵן הֵן מֵיאוּנֶיהָ.

A dilemma was raised before the Sages: What is the halakha if she was betrothed to another man without performing refusal of the first husband? Is her acceptance of the betrothal sufficient to indicate that she refuses the first husband? The Gemara suggests: Come and hear an answer from a baraita: If a minor girl did not refuse her husband but went and became betrothed to another man, then, as the Sages said in the name of Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira: Her betrothal constitutes her refusal.

אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: פְּלִיגִי רַבָּנַן עֲלֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה בֶּן בְּתִירָה אוֹ לָא? אִם תִּימְצֵי לוֹמַר פְּלִיגִי: בְּקִידּוּשִׁין, אוֹ אֲפִילּוּ בְּנִישּׂוּאִין? וְאִם תִּימְצֵי לוֹמַר פְּלִיגִי אֲפִילּוּ בְּנִישּׂוּאִין: הֲלָכָה כְּמוֹתוֹ אוֹ אֵין הֲלָכָה כְּמוֹתוֹ? וְאִם תִּימְצֵי לוֹמַר הֲלָכָה כְּמוֹתוֹ: בְּנִישּׂוּאִין אוֹ אֲפִילּוּ בְּקִידּוּשִׁין?

A dilemma was raised before the Sages: Do the Rabbis disagree with Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira or not? And further, if you say that they do disagree with him, do they disagree with him with regard to betrothal alone, or do they also disagree with him with regard to marriage? And if you say that they disagree even with regard to marriage, is the halakha in accordance with his opinion or is the halakha not in accordance with his opinion? And if you say that the halakha is in accordance with his opinion, is this only with regard to marriage, or is it even with regard to betrothal?

תָּא שְׁמַע, אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה בֶּן בְּתִירָה. הֲלָכָה — מִכְּלָל דִּפְלִיגִי.

The Gemara cites a tradition: Come and hear: Rav Yehuda said that Shmuel said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira with regard to both marriage and betrothal. From the fact that he ruled the halakha, one may derive by inference that the Rabbis disagree.

וְאַכַּתִּי תִּיבְּעֵי לָךְ: דַּהֲוָה נְסִיבָא מֵעִיקָּרָא, אוֹ דִלְמָא מִיקַּדְּשָׁא? תָּא שְׁמַע: דְּכַלָּתֵיהּ דְּאַבָּדָן, אִימְּרוּד, שַׁדַּר רַבִּי זוּגֵי דְּרַבָּנַן לְמִיבְדְּקִינְהוּ. אָמְרִי לְהוּ נְשֵׁי: חֲזוּ גַּבְרַיְיכוּ דְּקָאָתוּ. אָמְרִי לְהוּ: נִיהְווֹ גַּבְרַיְיכוּ דִּידְכוּ.

But still, you should raise the dilemma: Does Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira say that her betrothal to another counts as refusal even when she had initially been married or perhaps only if she was betrothed but not married beforehand? Come and hear: The daughters-in-law of Abdan rebelled against their husbands. Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi sent a pair of Sages to examine them and determine what could be done to rectify the matter. Some women said to the daughters-in-law: See, it is your husbands that are coming. They said back to them: Let them be your husbands.

אָמַר רַבִּי: אֵין לְךָ מֵיאוּן גָּדוֹל מִזֶּה. מַאי לָאו, דַּהֲוָה נְסִיבָא? לָא, דַּהֲוָה מִיקַּדְּשָׁא קִידּוּשֵׁי. וַהֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה בֶּן בְּתִירָה, וַאֲפִילּוּ בְּנִישּׂוּאִין דְּקַמָּא.

Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi said: There is no greater refusal than this. What is the case? Is it not that they were already married? The Gemara rejects this: No, they were merely betrothed, but not married. This story cannot establish unequivocally what the halakha is in the case when the girl is married. The Gemara nevertheless concludes: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira in all of these matters, even with regard to her marriage to the first husband: Even if she had actually been married to the first man, the marriage is invalidated by her betrothal to another.

רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר אוֹמֵר וְכוּ׳. אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: חוֹזְרַנִי עַל כׇּל צִדְדֵי חֲכָמִים וְלֹא מָצָאתִי אָדָם שֶׁהִשְׁוָה מִדּוֹתָיו בִּקְטַנָּה כְּרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר. שֶׁעֲשָׂאָהּ רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר כִּמְטַיֶּילֶת עִמּוֹ בֶּחָצֵר, וְעוֹמֶדֶת מֵחֵיקוֹ וְטוֹבֶלֶת וְאוֹכֶלֶת בִּתְרוּמָה לָעֶרֶב.

§ It is taught in the mishna: Rabbi Elazar says: The act of a minor girl is nothing. Rather, her status is as though she were a seduced unmarried woman. Rav Yehuda said that Shmuel said: I reviewed all the opinions of the Sages concerning these matters, and I did not find any person who applied a consistent standard with regard to a minor like Rabbi Elazar did. For Rabbi Elazar portrayed her as a girl walking with her husband in a courtyard, who stands up from his bosom after he engaged in intercourse with her, and immerses herself to become ritually pure, and partakes of teruma by evening as if there were no marital bond between them and as if she, as the daughter of a priest, could continue to partake of teruma. The daughter of a priest is prohibited from eating teruma once she is married to a non-priest.

תַּנְיָא, רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר אוֹמֵר: אֵין מַעֲשֵׂה קְטַנָּה כְּלוּם, וְאֵין בַּעְלָהּ זַכַּאי לֹא בִּמְצִיאָתָהּ, וְלֹא בְּמַעֲשֵׂה יָדֶיהָ, וְלֹא בַּהֲפָרַת נְדָרֶיהָ, וְאֵינוֹ יוֹרְשָׁהּ, וְאֵין מִיטַּמֵּא לָהּ. כְּלָלוֹ שֶׁל דָּבָר: אֵינָהּ כְּאִשְׁתּוֹ לְכׇל דָּבָר, אֶלָּא שֶׁצְּרִיכָה מֵיאוּן.

It is taught in a baraita: Rabbi Eliezer says: The act of a minor girl is nothing, and therefore her marriage is not valid. And her husband has no rights to items she finds, nor to her earnings; nor does he have the right to annul her vows; he does not inherit her assets if she dies; and if she dies he may not become ritually impure on her account if he is a priest, i.e., through his presence in the same room as her corpse. The principle is: She is not his wife in any sense, except that she must perform refusal in order to marry someone else.

רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ אוֹמֵר: בַּעְלָהּ זַכַּאי בִּמְצִיאָתָהּ, וּבְמַעֲשֵׂה יָדֶיהָ, וּבַהֲפָרַת נְדָרֶיהָ, וְיוֹרְשָׁהּ, וּמִיטַּמֵּא לָהּ. כְּלָלוֹ שֶׁל דָּבָר: הֲרֵי הִיא כְּאִשְׁתּוֹ לְכׇל דָּבָר, אֶלָּא שֶׁיּוֹצְאָה בְּמֵיאוּן.

Rabbi Yehoshua says: In the case of a minor whose mother or brother married her off, her husband has rights to items she finds, and to her earnings; and he has the right to annul her vows; and he inherits her assets if she dies; and if she dies he must become ritually impure on her account even if he is a priest. The principle is: She is his wife in every sense, except that she can leave him by means of refusal and does not require a bill of divorce.

אָמַר רַבִּי: נִרְאִין דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר מִדִּבְרֵי רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ. שֶׁרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר הִשְׁוָה מִדּוֹתָיו בִּקְטַנָּה, וְרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ חָלַק. מַאי חָלַק? אִי אִשְׁתּוֹ הִיא — תִּיבְעֵי גֵּט.

Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi said: The statement of Rabbi Eliezer appears to be more correct than the statement of Rabbi Yehoshua, as Rabbi Eliezer applied a consistent standard with regard to a minor, while Rabbi Yehoshua applied an inconsistent standard. The Gemara asks: In what way is his standard inconsistent? The Gemara answers: If she is his wife, she should require a bill of divorce from him.

לְרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר נָמֵי: אִי לָאו אִשְׁתּוֹ הִיא — מֵיאוּן נָמֵי לָא תִּיבְעֵי! אֶלָּא בִּכְדִי תִּיפּוֹק?!

According to Rabbi Eliezer too, there appears to be an inconsistency, as, if she is not his wife, she should not be required to perform refusal either. The Gemara answers: But shall she leave with no ritual at all? Some sort of act is required to indicate that their relationship is permanently severed. Rabbi Eliezer has a consistent standard, according to which the marriage of a minor has no substance and to dissolve it she need only indicate that she does not want her husband. Rabbi Yehoshua is inconsistent in treating the relationship as a marriage even though it can be dissolved easily.

רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר בֶּן יַעֲקֹב אוֹמֵר וְכוּ׳. הֵיכִי דָּמֵי עַכָּבָה שֶׁהִיא מִן הָאִישׁ וְעַכָּבָה שֶׁאֵינָהּ מִן הָאִישׁ? אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: תְּבָעוּהָ לִינָּשֵׂא, וְאָמְרָה: ״מֵחֲמַת פְּלוֹנִי בַּעְלִי״ — זוֹ הִיא עַכָּבָה שֶׁהִיא מִן הָאִישׁ. ״מֵחֲמַת בְּנֵי אָדָם שֶׁאֵינָם מְהוּגָּנִין לִי״ — זוֹ הִיא עַכָּבָה שֶׁאֵינָהּ מִן הָאִישׁ.

§ The mishna stated: Rabbi Eliezer ben Ya’akov says: If there is any obstruction in the matter due to the man, it is as if she were his wife. If there is any obstruction in the matter that is not due to the man, it is as if she were not his wife. The Gemara asks: What are the circumstances of an obstruction due to the man, and an obstruction that is not due to the man? Rav Yehuda said that Shmuel said: If someone proposed marriage to her and she said: I do not wish to marry on account of so-and-so, my husband, this is an obstruction that is due to the man. When she declined the proposal, she made it clear that she views herself as his wife. But if she says: I do not want to marry because the men suggested to me are not suitable for me, this is an obstruction that is not due to the man, and she is not considered to be his wife.

אַבָּיֵי בַּר אָבִין וְרַב חֲנִינָא בַּר אָבִין דְאָמְרִי תַּרְוַיְיהוּ: נָתַן לָהּ גֵּט — זוֹ הִיא עַכָּבָה שֶׁהִיא מִן הָאִישׁ, וְהוּא אָסוּר בִּקְרוֹבוֹתֶיהָ, וְהִיא אֲסוּרָה בִּקְרוֹבָיו, וּפְסָלָהּ מִן הַכְּהוּנָּה. מֵיאֲנָה בּוֹ — זוֹ הִיא עַכָּבָה שֶׁאֵינָהּ מִן הָאִישׁ, וְהוּא מוּתָּר בִּקְרוֹבוֹתֶיהָ, וְהִיא מוּתֶּרֶת בִּקְרוֹבָיו, וְלֹא פְּסָלָהּ מִן הַכְּהוּנָּה.

Abaye bar Avin and Rav Ḥanina bar Avin both say: If the minor’s husband gave her a bill of divorce, this is an obstruction that is due to the man, since in presenting the bill of divorce, the marriage is being treated as valid. Therefore, from then onward, he is prohibited from marrying her close relatives, and she is prohibited from marrying his close relatives; and, as a divorced woman, she is disqualified from marrying into the priesthood. However, if she refuses him, this is an obstruction that is not due to the man. Therefore, he is permitted to marry her close relatives, and she is permitted to marry his close relatives, and she is not disqualified from the priesthood, since her refusal annuls the marriage retroactively.

הָא קָתָנֵי לְקַמַּן: הַמְמָאֶנֶת בָּאִישׁ — הוּא מוּתָּר בִּקְרוֹבוֹתֶיהָ, וְהִיא מוּתֶּרֶת בִּקְרוֹבָיו, וְלֹא פְּסָלָהּ מִן הַכְּהוּנָּה. נָתַן לָהּ גֵּט — הוּא אָסוּר בִּקְרוֹבוֹתֶיהָ, וְהִיא אֲסוּרָה בִּקְרוֹבָיו, וּפְסָלָהּ מִן הַכְּהוּנָּה! פָּרוֹשֵׁי קָמְפָרֵשׁ.

The Gemara challenges: But it is taught explicitly below, in the following mishna: If a minor girl refuses a man, he is permitted to marry her close relatives and she is permitted to marry his close relatives, and he has not disqualified her from marrying into the priesthood. If he gave her a bill of divorce, he is prohibited from marrying her close relatives, and she is prohibited from marrying his close relatives, and he has disqualified her from marrying into the priesthood. Since the difference between refusal and a bill of divorce is already addressed in the following mishna, why is the same ruling repeated here? The Gemara answers: The following mishna is explaining the latter part of this mishna.

מַתְנִי׳ הַמְמָאֶנֶת בָּאִישׁ — הוּא מוּתָּר בִּקְרוֹבוֹתֶיהָ, וְהִיא מוּתֶּרֶת בִּקְרוֹבָיו, וְלֹא פְּסָלָהּ מִן הַכְּהוּנָּה. נָתַן לָהּ גֵּט — הוּא אָסוּר בִּקְרוֹבוֹתֶיהָ, וְהִיא אֲסוּרָה בִּקְרוֹבָיו, וּפְסָלָהּ מִן הַכְּהוּנָּה.

MISHNA: If a minor girl refuses a man, he is permitted to marry her close relatives, such as her mother or her sister, and she is permitted to marry his close relatives, such as his father or brother, and he has not disqualified her from marrying into the priesthood, as she is not considered divorced. However, if he gave her a bill of divorce, then even though the marriage was valid according to rabbinic law and not Torah law, he is prohibited from marrying her close relatives, and she is prohibited from marrying his close relatives, and he has disqualified her from marrying into the priesthood.

נָתַן לָהּ גֵּט וְהֶחְזִירָהּ, מֵיאֲנָה בּוֹ וְנִשֵּׂאת לְאַחֵר, וְנִתְאַרְמְלָה אוֹ נִתְגָּרְשָׁה — מוּתֶּרֶת לַחְזוֹר לוֹ. מֵיאֲנָה בּוֹ וְהֶחְזִירָהּ, נָתַן לָהּ גֵּט וְנִשֵּׂאת לְאַחֵר, וְנִתְאַרְמְלָה אוֹ נִתְגָּרְשָׁה — אֲסוּרָה לַחְזוֹר לוֹ.

If he gave her a bill of divorce but afterward remarried her, and she subsequently refused him and married another man, and then she was widowed or divorced from her second husband, she is permitted to return to him. Since she left him the last time by means of refusal, the refusal cancels the bill of divorce that he gave her previously, and her status is that of a minor girl who refused her husband, who is not forbidden to her first husband after a second marriage. However, if the order was different, and if she refused him and he subsequently remarried her, and this time he gave her a bill of divorce and she married another man, and she was widowed or divorced, she is forbidden to return to him, like any divorced woman who married another man.

זֶה הַכְּלָל: גֵּט אַחַר מֵיאוּן — אֲסוּרָה לַחְזוֹר לוֹ, מֵיאוּן אַחַר גֵּט — מוּתֶּרֶת לַחְזוֹר לוֹ.

This is the principle concerning a minor girl who refused her husband and then married several times: If the bill of divorce followed the refusal and she remarried, she is forbidden to return to him. If the refusal followed the bill of divorce, she is permitted to return to him. Since the refusal followed the bill of divorce it is clear that she was a minor and neither the marriage nor the divorce were valid by Torah law. However, when the ultimate separation is by means of a bill of divorce, there is no indication that she was a minor at the time and there is potential for confusion with an adult divorcée.

הַמְמָאֶנֶת בָּאִישׁ וְנִשֵּׂאת לְאַחֵר וְגֵירְשָׁהּ, לְאַחֵר וּמֵיאֲנָה בּוֹ, לְאַחֵר וְגֵירְשָׁהּ, זֶה הַכְּלָל: כֹּל שֶׁיּוֹצְאָה הֵימֶנּוּ בְּגֵט — אֲסוּרָה לַחְזוֹר לוֹ, בְּמֵיאוּן — מוּתֶּרֶת לַחְזוֹר לוֹ.

If a minor girl refuses one man and marries another, and he divorces her, and then she marries another man and refuses him, and then she marries another man and he divorces her, this is the principle for this case: With regard to anyone she leaves by means of a bill of divorce, it is prohibited for her to return to him. With regard to anyone she leaves by means of refusal, she is permitted to return to him.

גְּמָ׳ אַלְמָא אָתֵי מֵיאוּן וּמְבַטֵּל גֵּט.

GEMARA: It was taught in the mishna that if the man gave his minor wife a bill of divorce but subsequently remarried her and she refused him, and then she married someone else, she is permitted to remarry the first husband when her marriage to the second is concluded. Apparently, refusal comes and nullifies a bill of divorce.

וּרְמִינְהִי: הַמְמָאֶנֶת בָּאִישׁ וְנִשֵּׂאת לְאַחֵר וְגֵירְשָׁהּ, לְאַחֵר וּמֵיאֲנָה בּוֹ, לְאַחֵר וְגֵירְשָׁהּ, זֶה הַכְּלָל: כֹּל שֶׁיָּצְתָה הֵימֶנּוּ בְּגֵט — אֲסוּרָה לַחְזוֹר לוֹ, בְּמֵיאוּן — מוּתֶּרֶת לַחְזוֹר לוֹ. אַלְמָא לָא אָתֵי מֵיאוּן דְּחַבְרֵיהּ וּ[מְ]בַטֵּיל גִּיטָּא דִּידֵיהּ.

The Gemara raises a contradiction from the end of the mishna: If a minor girl refuses one man and marries another, and he divorces her, and then she marries another man and refuses him, and then she marries another man and he divorces her, this is the principle: With regard to anyone she leaves by means of a bill of divorce, she is prohibited from returning to him. With regard to anyone she leaves by means of refusal, she is permitted to return to him. Apparently, a refusal of another man does not come and nullify one’s own bill of divorce. If the refusal completely nullified the marriage to the second husband, there would be no obstacle to her remarrying her first husband, as an ex-wife who did not marry another man is permitted to remarry her first husband. However, the divorce, combined with the second marriage, does generate a prohibition, and she is prohibited from remarrying in this case.

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: תַּבְרַהּ, מִי שֶׁשָּׁנָה זוֹ לֹא שָׁנָה זוֹ.

Rav Yehuda said that Shmuel said: This mishna is disjointed, and he who taught this halakha, that she may remarry her first husband if she refused him after he divorced her, did not teach that halakha, that her refusal of another man does not render her permitted to her divorced husband.

אָמַר רָבָא: וּמַאי קוּשְׁיָא? וְדִלְמָא: מֵיאוּן דִּידֵיהּ מְבַטֵּל גֵּט דִּידֵיהּ, מֵיאוּן דְּחַבְרֵיהּ לָא מְבַטֵּל גִּיטָּא דִידֵיהּ. וּמַאי שְׁנָא מֵיאוּן דְּחַבְרֵיהּ דְּלָא מְבַטֵּל גִּיטָּא דִידֵיהּ — אַיְּידֵי דְּמַכֶּרֶת בִּרְמִיזוֹתָיו וּקְרִיצוֹתָיו אָזֵל מְשַׁבֵּשׁ וּמַיְיתֵי לַהּ, מֵיאוּן דִידֵיהּ נָמֵי לָא לִיבַטֵּל גִּיטָּא דִידֵיהּ — דְּאַיְּידֵי דְּמַכֶּרֶת בִּרְמִיזוֹתָיו וּקְרִיצוֹתָיו אָזֵיל מְשַׁבֵּשׁ וּמַיְיתֵי לַהּ!

Rava said: What is the difficulty here? Perhaps her refusal of him nullifies his bill of divorce, while her refusal of the other man does not nullify the original husband’s bill of divorce. The Gemara asks: In what way is her refusal of the other man different, that it does not nullify his bill of divorce? Isn’t it that because she is familiar with the intimations and gestures [keritzotav] of her first husband, he will lead her astray and bring her back to him, by causing her to refuse her new husband and then return to him? Consequently, it was decreed that she may not return to her first husband by refusing the second. But for this same reason the refusal against the first husband himself also should not nullify his own bill of divorce, as, since she is familiar with his intimations and gestures, he will lead her astray and bring her back to him after she has married another man.

הָא כְּבָר שַׁבְּשַׁהּ וְלָא אִישְׁתַּבַּשָׁא.

The Gemara answers: But he already tried to lead her astray and she was not led astray. In other words, he already remarried her after the divorce and she still refused him, which proves that he does not have sufficient influence to lead her astray.

אֶלָּא אִי קַשְׁיָא, דְּחַבְרֵיהּ אַדְּחַבְרֵיהּ קַשְׁיָא: מֵיאֲנָה בּוֹ וְהֶחְזִירָהּ, נָתַן לָהּ גֵּט וְנִשֵּׂאת לְאַחֵר, וְנִתְאַרְמְלָה אוֹ נִתְגָּרְשָׁה — אֲסוּרָה לַחְזוֹר לוֹ. טַעְמָא דְּנִתְאַרְמְלָה אוֹ נִתְגָּרְשָׁה. הָא מֵיאֲנָה — מוּתֶּרֶת לַחְזוֹר לוֹ, אַלְמָא אָתֵי מֵיאוּן דְּחַבְרֵיהּ וּמְבַטֵּל גִּיטָּא דִידֵיהּ.

But if there is a difficulty, it is the contradiction between one halakha involving another man and a different halakha involving another man that is difficult, as the mishna states: If she refused him and he subsequently remarried her, and this time he gave her a bill of divorce and she married another man, and she was widowed or divorced, she is prohibited from returning to her original husband. The reason is specifically that she was widowed or divorced by the other man. But if she had refused the second husband, she would be permitted to return to the first husband. Apparently, a refusal of the other man would have come and nullified his bill of divorce, permitting her to remarry the first husband, despite her erstwhile marriage to the other man.

וּרְמִינְהִי: הַמְמָאֶנֶת בָּאִישׁ וְנִשֵּׂאת לְאַחֵר וְגֵירְשָׁהּ, לְאַחֵר וּמֵיאֲנָה בּוֹ, זֶה הַכְּלָל: כֹּל שֶׁיָּצְתָה מִמֶּנּוּ בְּגֵט — אֲסוּרָה לַחְזוֹר לוֹ, בְּמֵיאוּן — מוּתֶּרֶת לַחְזוֹר לוֹ. אַלְמָא לָא אָתֵי מֵיאוּן דְּחַבְרֵיהּ וּמְבַטֵּל גִּיטָּא דִידֵיהּ!

This raises a contradiction, as it is taught later: If a minor girl refuses one man and marries another and he divorces her, and then she marries another and refuses him, this is the principle: With regard to anyone she leaves by means of a bill of divorce, she is prohibited from returning to him. With regard to anyone she leaves by means of refusal, she is permitted to return to him. Apparently, refusal of the other man cannot come and nullify his own bill of divorce.

אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר: תִּבְרַהּ, מִי שֶׁשָּׁנָה זוֹ לֹא שָׁנָה זוֹ. עוּלָּא אָמַר: כְּגוֹן שֶׁשִּׁלְּשָׁה בְּגִיטִּין, דְּמִיחַזְּיָא כִּגְדוֹלָה.

Rabbi Elazar said: This mishna is disjointed, and he who taught this halakha did not teach that halakha. Ulla said: The last clause, in which it says her refusal does not nullify the bill of divorce, is referring to a case where she was divorced three times. Since she was divorced three times, she appears to be an adult, and therefore the Sages did not allow her refusal to cancel the effect of the divorce.

מַאן תַּנָּא? אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב, מַאי דִּכְתִיב: ״מֵימֵינוּ בְּכֶסֶף שָׁתִינוּ עֵצֵינוּ בִּמְחִיר יָבֹאוּ״? בִּשְׁעַת הַסַּכָּנָה נִתְבַּקְּשָׁה הֲלָכָה זוֹ: הֲרֵי שֶׁיָּצְאָה מֵרִאשׁוֹן בְּגֵט וּמִשֵּׁנִי בְּמֵיאוּן, מַהוּ שֶׁתַּחֲזוֹר לָרִאשׁוֹן?

§ The Gemara asks: According to Rabbi Elazar, who holds that the mishna is disjointed, who is the tanna that taught that a minor may always remarry a husband she refused but not one who divorced her? Rav Yehuda said that Rav said: This can be determined based on the following incident. What is the meaning of that which is written: “We have drunk our water for money; our wood comes to us for a price” (Lamentations 5:4), implying that Torah, which is analogous to water, can be purchased with money. The Gemara explains: During the time of danger, i.e., religious persecution by the Romans, this halakhic ruling was requested: If she, a minor, left her first husband by means of a bill of divorce and her second by refusal, what is the halakha with regard to her returning to the first?

שָׂכְרוּ אָדָם אֶחָד בְּאַרְבַּע מֵאוֹת זוּז, וְשָׁאֲלוּ אֶת רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא בְּבֵית הָאֲסוּרִין, וְאָסַר. אֶת רַבִּי יְהוּדָה בֶּן בְּתִירָה בִּנְצִיבִין, וְאָסַר.

Those involved hired one person for four hundred dinars for the dangerous mission and asked Rabbi Akiva, who was incarcerated in prison by the Romans for teaching Torah, and he ruled that it is forbidden. They asked Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira in Netzivin, in Babylonia, and he also deemed it forbidden.

אָמַר רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל בְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי: לְזוֹ לֹא הוּצְרַכְנוּ. לְאִיסּוּר כָּרֵת הִתַּרְתָּ, לְאִיסּוּר לָאו — לֹא כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן.

Rabbi Yishmael, son of Rabbi Yosei, said: This question was not what they asked, as it was unnecessary: If you rendered permitted a prohibition for whose violation one is liable to receive excision from the World-to-Come [karet], i.e., if the prohibition against sexual intercourse with a married woman is dissolved by the refusal, as the marriage is nullified retroactively, then is it not clear all the more so that after a refusal, the regular prohibition against remarrying one’s ex-wife after she was married to another should be permitted? The opinion in the mishna that refusal does not cancel the effect of divorce is in accordance with that of Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira, while the opinion that she is permitted to return to her first husband after refusing the second one is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yishmael, son of Rabbi Yosei.

בְּרַם כָּךְ שָׁאֲלוּ: הֲרֵי הָיְתָה אֵשֶׁת אֲחִי אִמּוֹ, שֶׁהִיא שְׁנִיָּיה לוֹ, וּנְשָׂאָהּ אָחִיו מֵאָבִיו וּמֵת, מַהוּ שֶׁתְּמָאֵן הַשְׁתָּא וְתִעְקְרִינְהוּ לְנִישּׂוּאִין קַמָּאֵי, וְתִתְיַיבֵּם (צָרָתַהּ). יֵשׁ מֵיאוּן לְאַחַר מִיתָה בִּמְקוֹם מִצְוָה, אוֹ לָא?

Rabbi Yishmael, son of Rabbi Yosei, continued: Rather, this is what they asked: If the minor was the wife of someone’s mother’s brother, a secondary forbidden relative, i.e., a relative forbidden to him by rabbinic law, and afterward his paternal brother married her and died, so that she became eligible to him for levirate marriage, what is the halakha with regard to the following: May she refuse now and uproot the first marriage to the mother’s brother, so that she will no longer be a forbidden relative, and likewise her rival wife will not be the rival wife of a forbidden relative, so that her rival wife may enter into levirate marriage? In other words, in a case where there is a mitzva of levirate marriage, is refusal after the husband’s death valid or not?

שָׂכְרוּ שְׁנֵי בְּנֵי אָדָם בְּאַרְבַּע מֵאוֹת זוּז, וּבָאוּ וְשָׁאֲלוּ אֶת רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא בְּבֵית הָאֲסוּרִין, וְאָסַר. אֶת רַבִּי יְהוּדָה בֶּן בְּתִירָה בִּנְצִיבִין, וְאָסַר.

Those involved hired two people for four hundred dinars, and they came and asked Rabbi Akiva in prison and he deemed it prohibited. They asked Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira in Netzivin and he deemed it prohibited.

אָמַר רַב יִצְחָק בַּר אַשְׁיָאן: וּמוֹדֶה רַב, שֶׁמּוּתֶּרֶת לְאָחִיו שֶׁל זֶה שֶׁנֶּאֶסְרָה עָלָיו.

Rav Yitzḥak bar Ashyan said: Rav concedes that she is permitted to the brother of the man to whom she is forbidden. Rav Yitzḥak is referring to a case of a minor who refused her husband, remarried the same man, and was subsequently divorced, and then married another man and refused him. Although she may not remarry the first husband, she may marry his brother, despite the fact that one may not ordinarily marry one’s brother’s divorcée.

פְּשִׁיטָא, הוּא נִיהוּ דְּמַכֶּרֶת בִּרְמִיזוֹתָיו וּקְרִיצוֹתָיו, אֲבָל אָחִיו לָא! מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: לִיגְזַר הַאי אַטּוּ הַאי, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara asks: It is obvious. It is he, her former husband, whose hints and gestures she recognizes, but not those of his brother, so that there is no concern that the brother will persuade her to refuse her husband. The Gemara explains: Rav Yitzḥak bar Ashyan saw fit to point this out, lest you say: Issue a decree rendering it prohibited for her to marry this brother due to the risk that such a marriage would lead people to think she is permitted to marry that brother, her original husband. Therefore, he teaches us that no such decree was instituted.

וְאִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי, אָמַר רַב יִצְחָק בַּר אַשְׁיָאן: כְּשֵׁם שֶׁאֲסוּרָה לוֹ, כָּךְ אֲסוּרָה לָאַחִין. וְהָא אֵינָהּ מַכֶּרֶת בִּקְרִיצוֹתֵיהֶם וּרְמִיזוֹתֵיהֶם? גְּזֵירָה אָחִיו אַטּוּ הוּא.

And there are those who say a different version of the discussion: Rav Yitzḥak bar Ashyan said: Just as she is forbidden to him, to the man who divorced her, so is she forbidden to his brothers. The Gemara asks: But she is not familiar with their intimations and gestures. Why is it prohibited for her to marry them? The Gemara answers: It is a rabbinic decree concerning the ex-husband’s brothers due to him, the ex-husband. If she were to be permitted to her ex-husband’s brothers, people might mistakenly think that she is even permitted to remarry the ex-husband himself.

מַתְנִי׳ הַמְגָרֵשׁ אֶת הָאִשָּׁה וְהֶחְזִירָהּ — מוּתֶּרֶת לַיָּבָם.

MISHNA: With regard to one who divorces a woman and remarries her and then dies childless, his wife is permitted to enter into levirate marriage with her yavam,