Have you ever had a conversation with someone who was “all over the place,” jumping from one subject to another? In elegant Hebrew that is called פתח בכד וסיים בחבית, he began with a kad and ended with a havit, exactly what our Gemara says when it questions the language of the Mishna on Bava Kamma 27a: why did the Mishnah begin it’s example with a kad, a jug, and end with a havit, a barrel? The Gemara is often bothered by this sort of language inconsistency in the Mishnah. For example, in Bava Batra (17b) a law discussing a pit (bor) ends by referring to a wall (kotel). In Betzah (7b) the example is leavening (seor) and leavened bread (hametz). Often the answer is that the items are similar (enough) like our kad and havit, and the law is the same for both of them. Sometimes the answer is that the variety is coming to teach us something, as in this example:

“He began with the word “altar” and ended with the word “table,”. Rabbi Yoḥanan and Reish Lakish both say: When the Temple is standing the altar atones for a person; now that the Temple has been destroyed, it is a person’s table that atones for him,” (Hagigah 27a)

It is not that altar and table mean the same thing but that they are used for the same purpose. Scholars suggest that these variations are because Rabbi Judah the Prince took the parts of the Mishnah from different sources and kept their original language, assuming that people would understand that these are synonyms.

In our example, a kad (loosely translated as a jug) and a havit (a barrel) are similar, in fact the Gemara says that they are interchangeable terms and you only need to specify which if you are selling or buying them. But are they really the same? Both are vessels used for carrying, serving or storing liquids, like wine, oil and water. Both are relatively large, although they can come in different sizes, and are meant to be used for items that you need in large quantities, not for perfume or other very expensive liquids that need smaller containers. Both are not cooking vessels. They are made, at least in Biblical and Rabbinic times, from pottery. For more on pottery as a general category see here: https://hadran.org.il/author-post/pearls-of-wisdom/

But there are also differences between the two. The most obvious one is that kad is a much more ancient word than havit. A kad is referred to numerous times in the Bible while the word havit does not appear there at all; a havit on the other hand is the predominant word in Rabbinic literature. In the Bible we hear about a kad in a few different stories. The most famous one is the story in Bereshit about Rebecca watering the camels of Abraham’s servant despite the hard work involved:

“He had scarcely finished speaking, when Rebecca, who was born to Bethuel, the son of Milcah the wife of Abraham’s brother Nahor, came out with her jar (kadah) on her shoulder.” (Bereshit 24:15)

Rebecca not only gives the servant water from her kad, she proceeds to fill and empty it numerous times to water his many camels.

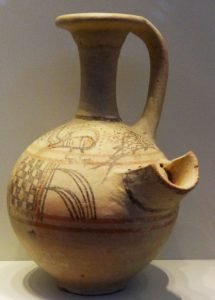

A Bronze Age storage vessel

Photo: Lauren Shachar

In two stories in the book of Kings, the kad is used for water as well as for flour: Elijah pours 4 kadim of water on the wood he sets up on his altar on Mount Carmel (Kings I 18:34) and he performs a miracle with the container (kad) of flour of a poor widow, making it last indefinitely:

“The jar (kad) of flour did not give out, nor did the jug (tzapachat) of oil fail, just as God had spoken through Elijah.” (Kings I 17:16)

A more unusual use of a kad is by Gideon, in his battle against the Midianites:

“He divided the three hundred men into three columns and equipped them all with a ram’s horn and an empty jar (kad), with a torch in each jar.” (Judges 7:16)

At Gideon’s word, the soldiers smashed the kadim, revealing the torches inside; the noise and the fire caused panic in the Midianite camp, ensuring the Israelite victory.

The word kad does not disappear in later periods but it is largely replaced by the word havit, as well as by other terms like kankan (קנקן). Havit is usually translated as a barrel, but it is a pottery vessel, not a wooden barrel like what we are used to today. The havit has a flat bottom, while the kad often has a pointed bottom. They can both have handles.

Both the kad and the havit can come in different sizes but the havit seems to be a larger version of this drinking vessel. A great example of the relative sizes of the two is in a story in Betzah. Rabbi Eliezer gave a lengthy sermon on Yom Tov. As his students tired and slowly snuck out to go home to their meals, Rabbi Eliezer called them out. The earliest to leave are the ones that he claims are the greediest, and have the most food, each later group has smaller containers, meaning they have less food awaiting them at home:

“When the first group left, he said: These must be owners of extremely large jugs [pittasin]. When a second group departed, he said: These are owners of barrels (haviyot), [which are smaller than pittasin.] Later a third group took its leave, and he said: These are owners of jugs (kadim), [even smaller than barrels].” (Betzah 15b)

Have we found examples of these vessels in archaeology? Yes, but we cannot clearly say what was a kad or a havit. In archaeological terms in Israel a drinking vessel is usually called a pach (פך) and a little one is a pachit. How do you know what is a drinking or storage jar and what is a cooking pot? Besides its basic shape, (tall and thin versus short and fat), anything that has a spout is meant for drinking. Here is a nice example:

Photo: Abbie Rosenbaum

Of course, most vessels are found in pieces and have to be put together, if possible. Rarely is a full and intact vessel found, like this lovely one:

Photo: Abbie Rosenbaum

If archaeologists are really lucky, they find remnants of what was in the container, which can be analyzed in the lab and then we can know what people ate and drank. Recently a multi-disciplinary team that included a brewer was able to take yeast from a Philistine vessel and use it to make Philistine style beer!

Philistine beer jug

Hanay, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Where was all this pottery made? In the Land of Israel, a center for pottery production were two villages in the Galilee, Kfar Hananya and Kfar Shikhin. The Gemara tells us that dishes made in these places were considered to be particularly strong:

“vessels from the village of Shikḥin and vessels from the village of Ḥananya also do not typically break” (Shabbat 120b)

Jug found in Kfar Shikhin

משלחת חפירות שיחין Shikhin archaeological expedition, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Kfar Hananya was so full of pottery that the Rabbinic version of “bringing coals to Newcastle” or “selling ice to Eskimos” is to bring potters to Kfar Hananya:

“He said: ‘What, Joseph, are you bringing straw to Efrayim, earthenware pots to Kfar Ḥananya, fleeces to Damascus, sorcery to Egypt – sorcery in a place of sorcerers?’” (Bereshit Rabba 86:5)

Although our Mishnah warns us of the danger of stumbling over pottery in a public place, we would be pretty excited to find an intact kad or havit on a nature stroll, as sometimes happens in Israel. Keep your eyes open!

Thank you to Abbie Rosenbaum, premier guide and archaeologist, for providing pictures and answering all my annoying pottery questions.