Did you ever learn to count in another language? Not so hard, right? Now how about counting in the letters of another language? That’s already a different story. Our Gemara shows us that the Rabbis were familiar with Greek numbers:

“Sumakhos said heina, he is a nazirite for one [term of naziriteship], if he said digon, he is a nazirite for two terms; if he said terigon, he is a nazirite for three terms; tetrigon, for four terms; pentigon, for five” (Bava Batra 164a)

The numbers here are Greek (or a bad pronunciation of Greek): Hen, duo, tria, tettara, pente: respectively one, two, three, four, five. Saying them commits you to that number of times of being a nazir. But Tosafot asks, why do we need to be told that? What does it matter if you say the number in Hebrew or Greek or English for that matter? Tosafot explains that even if you don’t know what the word means, saying it obligates you – that is the power of the word itself.

Greek was a language that many in the Land of Israel were familiar with (see here). The Rabbis liked to play with Hebrew words that sound like Greek ones, as in this remarkable passage:

“As Rabbi Yoḥanan said in the name of Rabbi Elazar: The Holy One, Blessed be He, has in His world only fear of Heaven alone, as it is stated . . . “And unto man He said: Behold [hen], the fear of the Lord, that is wisdom;” (Job 28:28), as in the Greek language they call one hen.” (Shabbat 31b)

But Greek, like Hebrew, does not only have names for numbers, it also assigns numerical value to the letters. This is clear from the suggestion in Shekalim that Greek letters mark the various stores of coins in the Temple:

“The funds are collected from the Temple treasury chamber with three baskets, each measuring three se’a. On the baskets is written, respectively, aleph, beit, gimmel, Rabbi Yishmael says: The letters written on them were in Greek, alpha, beta, gamma.” (Shekalim 3:2)

In the ancient world, there were no symbols for numbers. Numbers were spelled out, as in this passage in the Torah:

וַיִּהְיוּ֙ חַיֵּ֣י שָׂרָ֔ה מֵאָ֥ה שָׁנָ֛ה וְעֶשְׂרִ֥ים שָׁנָ֖ה וְשֶׁ֣בַע שָׁנִ֑ים שְׁנֵ֖י חַיֵּ֥י שָׂרָֽה׃

“Sarah’s lifetime—the span of Sarah’s life—came to one hundred and twenty-seven years.” (Bereshit 23:1)

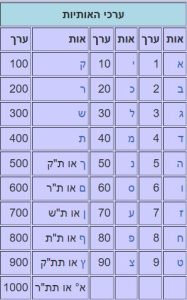

By the Rabbinic period, numbers were also written as letters. Each letter had a numerical value: aleph equals one, bet equals two, etc, and so numbers could be written as a combination of letters: kaf כ =20, zayin ז = 7, so כז = 27.

This system, which seems odd and laborious today, made sense before the widespread use of what are called Arabic numerals, which only came to Europe around the tenth century CE. Even today, pages of the Gemara are numbered with Hebrew letters, and chapters and verses in the Bible also use that system. The Hebrew year is also written out in letters, which can be a source of frustration when trying to figure out dates on graves and signs:

When did Rabbi Moshe die and how many years did he serve as a judge?

אריאל פלמון Ariel Palmon, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

In the early days of Zionism, Hebrew letters were sometimes used in lieu of numerals on clocks or on houses:

My another account, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The use of letters to correspond to numbers was not unique to the Jews, and like the Jews, the numbers and letters were played with, to create double meanings or to write codes. The Greek term for this is isosephy, Greek for “equal count.” The sum of the letters of one word, can equal the sum of the letters of another word, to show how they are related, similar etc. Probably the most famous, if disputed, example of this is in the New Testament. In the book of Revelations (13:18) the number 666 is supposed to equal the number of a man. Much ink has been spilled over explaining this passage but one possible, simple explanation is that the Aramaic name for Nero, נרון קסר, a man not particularly friendly to the early Christians, equals 666. A similar idea is cited by the Roman historian Suetonius: the letters for Nero equal the letters for “he killed his own mother.” A more lighthearted example was found as graffiti in Pompeii: “I love her whose number is 545.”

In Hebrew this word and number play is known as gematria. It is one of the Rabbis’ many literary techniques. By showing that one word equals another word, you create a connection and a lesson. When Jacob dreams of a ladder, he is really dreaming that his descendants will receive the Torah at Sinai:

“Another matter, “behold, a ladder” – this is Sinai. The letters of this equals the letters of that.” (Bereshit Rabba 68:12)

Another oft-mentioned example: the letters of the word יין -wine- equal seventy, as do the letters of word סוד – secret. Thus, when wine goes in, a secret comes out (Eruvin 65a).

Not only the technique but also the word gematria comes from the Greek. There are different explanations for what it means. Some scholars say it is derived from geometry, which literally means measuring land. This was a shorthand for any kind of counting. A more fun explanation divides the word into gamma, the third letter of the Greek alphabet and tria, the number three. Literally: gamma equals tria, a classic use of gematria!

Print of the letter gamma

Public domain, Wikipedia Commons

Basic gematria assigns a numerical value to each letter. There are more complicated versions as well which resemble code breaking: atbash אתבש, where aleph signifies tav, bet signifies shin and so on; use of the final letters אותיות סופיות , squaring letters and more.

The Rabbis used gematria to illustrate a point or back up an idea. They did not use it to determine halacha and rarely used it to innovate a new idea. Some later commentators loved gematria, others did not see much in it. The Baalei Tosafot in Northern France and the Hasidei Ashkenaz in Germany were enamored of gematria, as were later Kabbalists and even followers of Sabbatai Zevi. Nachmanides and Abraham ibn Ezra on the other hand warn against putting too much store in it. Here is the Ibn Ezra’s comment on the Rabbinic idea that Abraham took his servant Eliezer to battle, since Eliezer in gematria equals 318, the number cited in the text as Abraham’s soldiers:

“His trained men: Those who identify Abraham’s trained men with his servant Eliezer on the basis of the numerical value of the latter’s name are indulging in Midrash, as Scripture does not speak in gematria. With this type of interpretation one can interpret any name as he wishes, both in a positive and a negative manner. Eliezer is to be taken literally.” (Abraham Ibn Ezra on Bereshit 14:14)

Does gematria equal fun or education or both?

Thanks to Rabbi Jonathan Mishkin whose value is always equal to great husband.