How fast does news travel? In our world of Whatsapp and Twitter, Instagram and TikTok, very fast. In the Mishnaic world, a little slower. The time it took to find out about a squatter on your land is an important element in determining chazaka, the squatter’s claim on the land:

“MISHNA: There are three lands with regard to presumptive ownership: Judea, and Transjordan, and the Galilee. [If the prior owner of the field] was in Judea and [another] took possession of his field in the Galilee, or if he was in the Galilee and another took possession of his field in Judea, [the possessor does not establish] presumptive ownership until [the one possessing the field] will be with the prior owner in one province.”

If you are not living near your property, you may be unaware that someone is on it and therefore you will not lodge a complaint. People did not talk about land in other parts of the country and the owner would not have visited so frequently. Even today, when transportation is so much easier, how often do residents of northern Israel get to Jerusalem, and vice versa?

This tripartite division of the land of Israel appears in a few other places. Two have to do with agriculture: when do fruits grow and when is it spring in various parts of the country can determine the halacha for that area:

“There are three territories in respect to the law of removal [of sheviit produce]: [these are]: Judea, Transjordan, and Galilee, and there are three territories in each one.” (Sheviit 9:2)

In a sabbatical year, once a fruit or vegetable no longer grows in the field, you have to remove it from your house, this is called biur. But depending on the climate and the topography, fruits ripen at different times, a phenomenon that is easy to see today as you see ripe pomegranates already on the trees in the hot Jordan Valley, while they are still small and hard in the hills of Gush Etzion. Different ripening times mean different biur times.

A different distinction is connected to society. A man cannot marry a woman from one region and force her to move to another; it may be hard for her to adjust away from her home and family:

“Eretz Yisrael is divided into three separate lands with regard to marriage: Judea, Transjordan, and the Galilee.” (Ketubot 13:10)

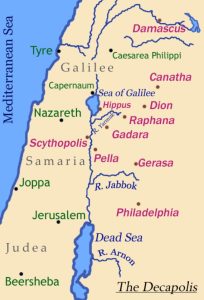

In all these examples, we hear about Judah, the Galilee and the Transjordan. Other places leave out Transjordan and only mention Judah and Galilee, like in the discussion about marriage customs (see here). Professor Zeev Safrai suggests that the mishnayot that include Transjordan were composed earlier, since that area had a robust Jewish population in Second Temple times but suffered a great decline with the destruction of the Temple and then the Bar Kokhba Revolt. By the time of the Gemara, Transjordan was largely irrelevant for Jews. Josephus in his The Jewish War talks about Transjordan, which he calls by the Greek name Perea (which means the same thing as trans or עבר in Hebrew, the land beyond) as an important Jewish center since that is what it was in his time. Other parts of the country, like Samaria, the Jezreel Valley and the coastal plain are not included in this categorization because there Jews were the minority and the majority population were either Samaritans or pagans.

What do we know about Transjordan? Is it even part of the Land of Israel? In Biblical times, two and a half tribes settle there; on the other hand, Moses dies there and he famously sees the land from afar and does not enter it. In or out?

Transjordan is the land to the east of the river Jordan. It mirrors the western bank of the Jordan in having a flat plain that stretches for a few kilometers, and then ascends to a mountain ridge. But Jordan’s mountains are much higher than Israel’s. Transjordan has a number of deep and important wadis, or riverbeds, that cut across it from east to west: the Zared, Arnon, the Yabok, and the Yarmuk.

Nichalp, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

The mountain ridge that extends from north to south has a major road on it called the King’s Highway, Derech haMelech in Hebrew. We first hear of it when Moses asks permission to traverse the land of Edom, promising that the Israelites will stay on the road, not go off into the fields:

“Allow us, then, to cross your country. We will not pass through fields or vineyards, and we will not drink water from wells. We will follow the king’s highway, turning off neither to the right nor to the left until we have crossed your territory.” (Bamidbar 20:17)

This King’s Highway was a major throughfare for centuries and exists today, albeit in a paved version. Tourists travel it to reach sites like Madaba, Mount Nebo and Petra.

Kings Highway highlighted

The eastern side of the Jordan is where the Children of Israel entered the land with Joshua. But it is also the place where Moses battled Sihon and Og, and gained valuable territory that was then settled by the tribes of Reuven, Gad and half of the huge tribe of Menashe. Throughout the next few centuries, Transjordan’s land changed hands: the tribes shared it, they were conquered by or conquered the nations of Edom, Moab, Ammon, Midian and Aram. Only with the Assyrian invasions in the eighth century BCE did all these groups end their time on the land.

Makeandtoss, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

By Hasmonean times (second century BCE) much of the central part of Transjordan had returned to Jewish hands. It was part of Herod’s kingdom as well and got the new name Perea. Perea had a strong Jewish community and it was also a waystation for Jews traveling to Jerusalem, to the Temple. Many Jews feared traveling through Samaria; the Samaritan population was often hostile and their land was considered impure. So some would cross the Jordan in the north, travel south through Perea, and re-cross near Jericho. From there they would travel west towards Jerusalem, on the winding desert highway.

Wikipedia User:Andrew c, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

With the destruction of the Temple and subsequent revolts, as well as the rise of Christianity, Transjordan became less Jewish and more of a Byzantine Christian stronghold. Churches and monasteries were built and the Jewish population dwindled. Other centers, like Babylonia and Alexandria became more important.

Many centuries later, Zeev Jabotinsky, the founder of the Revisionist Zionist movement, wrote a poem called The Left of the Jordan. Its theme is that the Jordan has two banks, and both of them belong to the country of Israel:

שתי גדות לירדן, זו שלנו זו גם כן

This poem, which was also the source for the symbol of the Etzel, was written in 1929, seven years after the British decided to take the eastern bank of the Jordan and create the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan there. While some of the Zionist establishment made peace with that decision, Jabotinsky and his followers would not give up on the “left bank” (left if you are sailing south on the Jordan), seeing both east and west as integral parts of Israel.

Avi1111 dr. avishai teicher, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons