One of the extensive list of things that render a Kohen’s work unfit is not standing directly on the floor of the Temple.

“Rabbi Ami raises a dilemma: If one of the stone tiles of the Temple floor came loose and began to wobble, and the priest stood on it, what is the halakha?” (Zevachim 24a)

The Gemara’s question prompts us to try to reconstruct how the Temple floor looked. Ostensibly this is a question that is impossible to answer since we cannot excavate underneath the Temple Mount in its current situation. However, we can do three things – look at the sources, look at the floor of the Temple Mount today and study the remains that were taken out from underneath the mountain.

The lengthy description of Solomon’s Temple includes a few words about the stones used there:

“The king ordered huge blocks of choice stone אבנים יקרות to be quarried, so that the foundations of the house might be laid with hewn stones” (Kings I 5:31)

Rashi explains that the word translated here as choice, יקרות means heavy. The outdoor areas of the Temple Mount needed to be paved with resilient heavy stones that could withstand the extreme heat and cold of Jerusalem. Maimonides uses this same word יקרות in his description of the courtyard paving:

“Choice stones were laid on the floor of the entire courtyard.” (Maimonides Bet HaBechira 1:10)

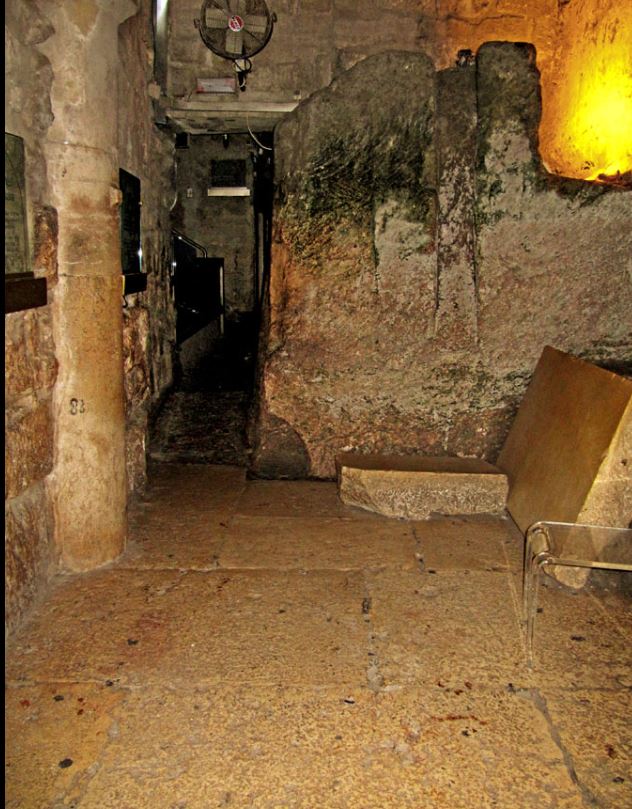

What were these heavy stones? We can see remains of them in several areas. Massive paving stones, carved from local limestone, were used to pave the main street that ran alongside the western wall of the Temple Mount. They can be seen near Robinson’s Arch at the Southern Wall excavations, as well as at the opposite end of this street, in the Western Wall tunnels. Dr. Leen Ritmeyer notes that there are still some on the Temple Mount itself, near the Cotton Gate and under the Dome of the Spirits, both on the western side of the platform. Clearly they were durable if they are still being used two thousand years later!

Paving stones in the Western Wall tunnels, note the unused stone standing up on the right

Tamar HaYardeni Wikimedia Commons

However, in recent years we have discovered a different, much more unusual flooring. The reason we could find it is because of the sifting project, an incredible effort by Jerusalem archaeologists to turn lemons into lemonade. In 1999 Tzachi Dvira noticed that the Waqf was illegally digging under the Temple Mount in order to build a massive mosque. He was understandably upset – this was not an archaeological excavation but a construction project, with bulldozers pulling out tons of dirt along with precious artifacts from one of the world’s most sensitive and valuable sites. However, he understood that this was a way to explore this site, which otherwise was completely off limits to archaeologists. The dirt was hauled from the Kidron Valley to a site on the Mount of Olives in 2004 and volunteers have been sifting through it ever since, finding things ranging from Ottoman pipes to First Temple stone weights.

One of the items that turned up frequently were colored stones shaped into triangles, squares and other shapes. Unlike mosaic stones, which are usually square and of a relatively uniform size and shape, these pieces were varied. About one hundred of them can be dated to the Herodian (late Second Temple) period. One of the supervisors at the dig, Frankie Snyder, noticed these pieces and using her math background and her knowledge of Herodian period sites, she began to reconstruct what the floors looked like.

The technique used here was called opus sectile, Latin for cut work. The idea was to take stone in all different colors and materials: marble, chalk, alabaster and more – and cut them in shapes to make intricate patterns. This style was popular in Rome and we have some magnificent examples from Hadrian’s villa:

Opus sectile is different than mosaics, which use small pieces to create a pattern. Here is an example of both techniques used together:

Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Herod, as an admirer of all things Roman, brought the technique of opus sectile to Israel. He used it in his own palaces, like this simple pattern in the Masada bathhouse (note that many of the tiles are missing, stolen over the centuries) :

Bukvoed, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

From the king, the practice spread towards the merely wealthy. In the houses of the Kohanim discovered in Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter we have examples of opus sectile tiling:

Roded Shlomo Pikiwiki Israel, CC BY 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons

Herod wanted the Temple to be a showstopping piece of art and our sources say that it was. It stands to reason that he would include the exclusive and beautiful opus sectile tiling. He imported stone from all over the Roman Empire; the pieces we have found come from Tunisia, Turkey, Greece and Egypt. But where would he put this gorgeous floor? It was much too delicate and precious to withstand the rigors of the Temple courtyard. Snyder and Professor Gaby Barkai suggest that it was put in covered areas, perhaps in the colonnades beneath the Royal Stoa on the south or even in the various chambers around the Women’s Court. Whoever was lucky enough to see these patterns must have remembered them for a long time. Perhaps the author of this description in the Gemara was one of those eyewitnesses:

“One who has not seen Herod’s building has never seen a beautiful building in his life. With what did he build it? Rabba said: With stones of white and green marble. There are those who say that he built it with stones of blue, white, and green marble . . it looks like the waves of the sea.” (Bava Batra 4a)

אסף אברהם, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons