Questions are raised against Rav Sheshet’s opinion, that carrying the blood to be sprinkled could be performed with the left hand. An additional question is brought by Rav Papa (continuation from the previous pages) regarding the handful of the incense. Rabbi Yehushua ben Levi asks a question about the handful – if a Kohen Gadol took the handful and died, would his replacement be able to take that handful or would he need to take his own? Rabbi Chanina’s reaction to his question spurs a whole discussion in and of itself regarding when Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi was born – in the generation before or after Rabbi Chanina? How does his question relate to the debate regarding what happens if the Kohen Gadol dies after slaughtering the bull – does his replacement need to slaughter a new one? What is the answer to Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi’s question? The gemara brings two different answers. Does the Kohen Gadol take the incense in his hands again when he is inside the Holy of Holies? If so, how is it done, technically? If the Kohen Gadol dies after slaughtering but before sprinkling the bull’s blood, does his replacement need to slaughter a new bull? Two sides of the debate are brought and analyzed.

Yoma 49

Share this shiur:

This week’s learning is sponsored for the merit and safety of Haymanut (Emuna) Kasau, who was 9 years old when she disappeared from her home in Tzfat two years ago, on the 16th of Adar, 5784 (February 25, 2024), and whose whereabouts remain unknown.

This week’s learning is dedicated of the safety of our nation, the soldiers and citizens of Israel, and for the liberation of the Iranian people. May we soon see the realization of “ליהודים היתה אורה ושמחה וששון ויקר”.

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Today’s daily daf tools:

This week’s learning is sponsored for the merit and safety of Haymanut (Emuna) Kasau, who was 9 years old when she disappeared from her home in Tzfat two years ago, on the 16th of Adar, 5784 (February 25, 2024), and whose whereabouts remain unknown.

This week’s learning is dedicated of the safety of our nation, the soldiers and citizens of Israel, and for the liberation of the Iranian people. May we soon see the realization of “ליהודים היתה אורה ושמחה וששון ויקר”.

Today’s daily daf tools:

Delve Deeper

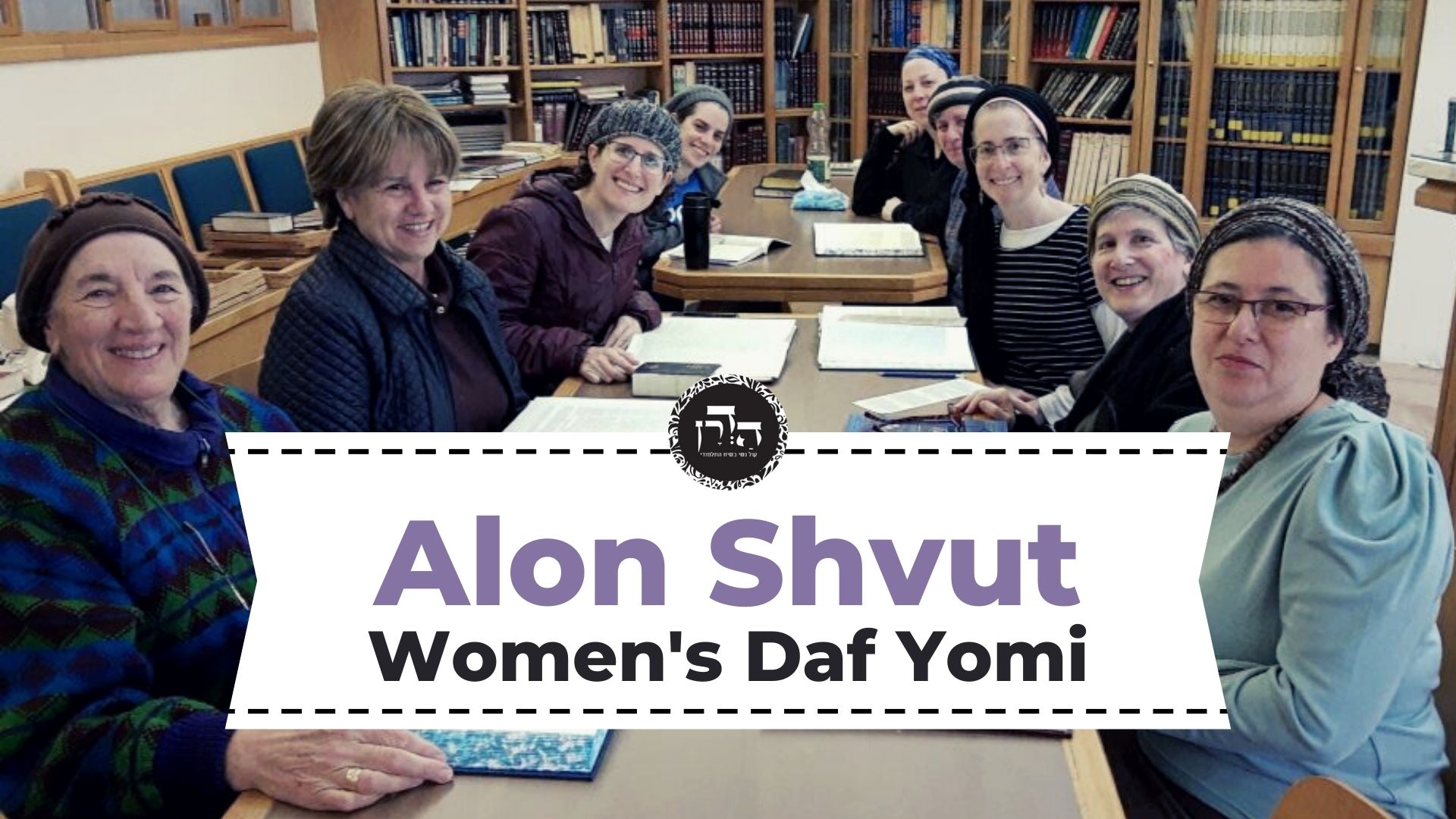

Broaden your understanding of the topics on this daf with classes and podcasts from top women Talmud scholars.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Yoma 49

מֵיתִיבִי: זָר, וְאוֹנֵן, שִׁיכּוֹר, וּבַעַל מוּם, בְּקַבָּלָה וּבְהוֹלָכָה וּבִזְרִיקָה — פָּסוּל. וְכֵן יוֹשֵׁב, וְכֵן שְׂמֹאל — פָּסוּל! תְּיוּבְתָּא.

The Gemara raises an objection from a baraita: With regard to receiving, carrying, or sprinkling blood, if a non-priest, a mourner on his first day of mourning, a drunk priest, and a blemished priest, performed the rite, it is disqualified. And likewise if the priest was sitting, and likewise if he performed one of these rites with his left hand, it is disqualified. This statement contradicts the ruling of Rav Sheshet. The Gemara concludes: This is indeed a conclusive refutation, and Rav Sheshet’s opinion is rejected.

וְהָא רַב שֵׁשֶׁת הוּא דְּאוֹתְבַהּ, דַּאֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב שֵׁשֶׁת לְאָמוֹרֵיהּ דְּרַב חִסְדָּא, בְּעִי מִינֵּיהּ מֵרַב חִסְדָּא: הוֹלָכָה בְּזָר מַהוּ? אֲמַר לֵיהּ: כְּשֵׁירָה, וּמִקְרָא מְסַיְּיעֵנִי: ״וַיִּשְׁחֲטוּ הַפָּסַח וַיִּזְרְקוּ הַכֹּהֲנִים מִיָּדָם וְהַלְוִיִּם מַפְשִׁיטִים״!

The Gemara asks: But wasn’t Rav Sheshet the one who objected on the basis of this very baraita? As Rav Sheshet said to the interpreter of Rav Ḥisda: Raise the following dilemma before Rav Ḥisda: What is the halakha with regard to carrying the blood performed by a non-priest? He said to him: It is valid, and a verse supports me: “And they slaughtered the Paschal offering and the priests sprinkled with their hand, and the Levites flayed” (II Chronicles 35:11). This verse indicates that the priests took the blood from the hands of the Levites, from which it can be inferred that the Levites carried the blood from the place of slaughtering to the place of sprinkling.

וּמוֹתֵיב רַב שֵׁשֶׁת: זָר וְאוֹנֵן, שִׁיכּוֹר וּבַעַל מוּם, בְּקַבָּלָה וּבְהוֹלָכָה וּבִזְרִיקָה — פָּסוּל, וְכֵן יוֹשֵׁב וְכֵן שְׂמֹאל — פָּסוּל.

And Rav Sheshet objected based on the aforementioned baraita: With regard to receiving, carrying, or sprinkling blood, if a non-priest, a mourner on his first day of mourning, a drunk priest, and a blemished priest, performed the rite, it is disqualified. This statement proves that carrying cannot be performed by a non-priest. Since Rav Sheshet himself cited this baraita in his objection, he was certainly familiar with it. How, then, could he issue a ruling in contradiction to the baraita?

בָּתַר דְּשַׁמְעַהּ הֲדַר אוֹתְבַהּ. וְהָא רַב חִסְדָּא קְרָא קָאָמַר? דַּעֲבוּד מַעֲשֵׂה אִיצְטְבָא.

The Gemara explains: After Rav Sheshet heard the baraita that was cited against his opinion, he objected to the ruling of Rav Ḥisda from that same baraita. At first Rav Sheshet was unaware of the baraita, which is why he ruled against it, but when he learned it, he relied upon it to object to Rav Ḥisda’s statement. The Gemara asks: But didn’t Rav Ḥisda cite a verse in support of his opinion? How can a baraita contradict a verse? The Gemara answers: The verse does not mean that the Levites walked with the blood, but rather that they acted like benches and merely stood holding the bowls of blood in their hands.

בָּעֵי רַב פָּפָּא: חָפַן חֲבֵירוֹ, וְנָתַן לְתוֹךְ חׇפְנָיו מַהוּ? ״מְלֹא חׇפְנָיו״ בָּעֵינַן, וְהָא אִיכָּא! אוֹ דִילְמָא: ״וְלָקַח״ ״וְהֵבִיא״ בָּעֵינַן? וְהָא לֵיכָּא! תֵּיקוּ.

§ The Gemara returns to the issue of appropriate methods for taking handfuls of incense. Rav Pappa raised a dilemma: What is the halakha with regard to a case where another priest scooped and placed the incense into the hands of the High Priest? The Gemara clarifies the two sides of the question: Do we require: “His full hands,” and that is fulfilled here, as in practice the High Priest has a handful of incense? Or perhaps we require that the High Priest must fulfill the mitzvot: “And he shall take…and he shall bring” (Leviticus 16:12), and that is not the case here, as the High Priest did not scoop and take the incense himself? This question was also left unanswered, and the Gemara concludes: Let it stand unresolved.

בָּעֵי רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: חָפַן וָמֵת, מַהוּ שֶׁיִּכָּנֵס אַחֵר בַּחֲפִינָתוֹ? אָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא: בֹּא וּרְאֵה שְׁאֵלַת הָרִאשׁוֹנִים.

§ Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi raised a dilemma: If the High Priest scooped and died, what is the halakha with regard to the possibility that another High Priest may replace him and enter with his handful? May the second priest enter the Holy of Holies with the incense that the first priest scooped, or must he start from the beginning of the process? Rabbi Ḥanina said to his students in excitement: Come and see that Sages from a later generation were able to ask a difficult question on par with the question of the earlier generations. Even I, Rabbi Ḥanina, asked this same question, which was posed by my elder, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi.

לְמֵימְרָא דְּרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי קַשִּׁישׁ? וְהָאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: לִי הִתִּיר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא לִשְׁתּוֹת שַׁחֲלַיִים בְּשַׁבָּת!

The Gemara analyzes this comment: Is that to say that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi was older than Rabbi Ḥanina, which is why Rabbi Ḥanina referred to him as an early Sage? But didn’t Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi say: Rabbi Ḥanina permitted me to drink cress juice on Shabbat for medicinal purposes. Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi’s deference to Rabbi Ḥanina shows that Rabbi Ḥanina was older than him.

לִשְׁתּוֹת, פְּשִׁיטָא? דִּתְנַן: כׇּל הָאוֹכָלִין אוֹכֵל אָדָם לִרְפוּאָה, וְכׇל הַמַּשְׁקִין שׁוֹתֶה!

Since it has been raised, the Gemara addresses the issue of cress juice on Shabbat: Did Rabbi Ḥanina permit him to drink cress juice? It is obvious that it is permitted to drink this juice; why would it be prohibited? As we learned in a mishna: All types of food that healthy people eat may be eaten by people even for medicinal purposes, and one may likewise drink all drinks for medicinal purposes, as the Sages did not include these in their decree against taking medicine on Shabbat.

אֶלָּא: לִשְׁחוֹק וְלִשְׁתּוֹת שַׁחֲלַיִים בְּשַׁבָּת. הֵיכִי דָמֵי? אִי דְּאִיכָּא סַכַּנְתָּא — מִשְׁרָא שְׁרֵי. וְאִי דְּלֵיכָּא סַכַּנְתָּא — מֵיסָר אֲסִיר! לְעוֹלָם דְּאִיכָּא סַכַּנְתָּא, וְהָכִי קָא מִבַּעְיָא לֵיהּ: מִי מַסְּיָא, דְּנֵיחוּל עֲלַיְיהוּ שַׁבְּתָא, אוֹ לָא מַסְּיָא וְלָא נֵיחוּל עֲלַיְיהוּ שַׁבְּתָא.

Rather, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi’s question was: Is it permitted to grind and drink cress on Shabbat? The Gemara asks: What are the circumstances? If it involves a situation where there is danger to life, and this is the prescribed cure, it is certainly permitted; and if it is a case where there is no danger, it is prohibited as labor on Shabbat. The Gemara answers: Actually, the question concerns a case where there is a life-threatening danger, and this is the dilemma that he raised before him: Does this drink heal, which would mean that it is appropriate to violate Shabbat for it, or does it not heal, and therefore one should not violate Shabbat for it?

וּמַאי שְׁנָא רַבִּי חֲנִינָא? מִשּׁוּם דְּבָקִי בִּרְפוּאוֹת הוּא. דְּאָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא: מֵעוֹלָם לֹא שְׁאָלַנִי אָדָם עַל מַכַּת פִּרְדָּה לְבָנָה וְחָיָה.

The Gemara asks: And if this was not a halakhic question but a medical one, what is different about this question that led him to ask it specifically of Rabbi Ḥanina? The Gemara explains: Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi asked Rabbi Ḥanina because he is an expert in medicines, as Rabbi Ḥanina said: No man ever consulted me about a wound inflicted by a white mule and recovered. This shows that people came to Rabbi Ḥanina for medical advice.

וְהָא קָא חָזֵינַן דְּחַיֵּי! אֵימָא: וְחָיָית. וְהָא קָא חָזֵינַן דְּמִיתַּסִּי! בְּסוּמָּקָן אִינְהוּ וְחִיוָּרָן רֵישׁ כַּרְעַיְהוּ קָאָמְרִינַן.

The Gemara expresses surprise at this claim: But we see that people who are kicked by mules do survive. The Gemara answers that instead it should say: No man ever consulted me about a wound of this kind and the wound survives, i.e., the wound never heals. The Gemara challenges this statement as well: But we see that it does heal. The Gemara responds: We say that the wound will never heal only when the mules are red and the tops of their legs are white.

מִכׇּל מָקוֹם, שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ דְּרַבִּי חֲנִינָא קַשִּׁישׁ? אֶלָּא הָכִי קָאָמַר: שְׁאֵלָתָן כִּשְׁאֵילָה שֶׁל רִאשׁוֹנִים.

The Gemara returns to its previous question. In any event, one can learn from this discussion that Rabbi Ḥanina was older than Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi. Why, then, does Rabbi Ḥanina refer to Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi as a member of an earlier generation? Rather, we must explain that this is what he said, i.e., that Rabbi Ḥanina’s statement should be understood as follows: Their question is like the question of the early ones. In other words, Rabbi Ḥanina meant that this question, posed by a member of a later generation, is as difficult as that of the early Sages.

וּמֵי אָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא הָכִי? וְהָאָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא: ״בְּפַר״, וְלֹא בְּדָמוֹ שֶׁל פַּר.

The Gemara asks: And did Rabbi Ḥanina actually say that this question, of one High Priest using the incense scooped by another, was difficult to answer? But didn’t Rabbi Ḥanina say: “With this Aaron shall come into the sacred place, with a bull” (Leviticus 16:3); this means that the High Priest must enter with the offering of a bull and not with the blood of the bull? In other words, the High Priest himself must slaughter his bull. Should a different priest slaughter the bull, receive its blood, and then die, the priest who replaces him may not enter the Holy of Holies with the blood of the bull slaughtered by his predecessor. Instead, he must bring a new bull, slaughter it, collect its blood, and take that blood inside.

וְאָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא: קְטוֹרֶת שֶׁחֲפָנָהּ קוֹדֶם שְׁחִיטַת הַפָּר לֹא עָשָׂה וְלֹא כְלוּם!

And likewise, Rabbi Ḥanina said: If the priest scooped the incense before the slaughtering of the bull, he did nothing, as the handful of incense must be taken after the slaughter of the bull. If so, in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Ḥanina, it is impossible for a priest to enter the Sanctuary with the handful taken by his fellow priest. The reason is that if the first priest died after the handful was taken, he certainly has not yet entered with the blood he collected from the bull. Consequently, his slaughter was not effective for the substitute priest, who must repeat the entire service from the slaughter onward.

הָכִי קָאָמַר: מִדְּקָא מִיבַּעְיָא לֵיהּ, הָא מִכְּלָל דְּקָסָבַר ״בְּפַר״, וַאֲפִילּוּ בְּדָמוֹ שֶׁל פַּר. וּלְמַאי דִּסְבִירָא לֵיהּ — שְׁאִילָתוֹ כִּשְׁאֵילַת הָרִאשׁוֹנִים.

The Gemara explains that this is what Rabbi Ḥanina said: From the fact that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi raised this dilemma, it can be understood by inference that he holds that the verse “with a bull” means that the High Priest may enter the Holy of Holies even with the blood of a bull. This means that the second priest does not have to go back and slaughter a second bull. And according to that which Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi maintains, his question is like the question of the earlier generations. Although the question does not arise according to the opinion of Rabbi Ḥanina himself, according to the ruling of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, the question is indeed a difficult one.

מַאי הָוֵי עֲלַהּ? אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא: אִי חוֹפֵן חוֹזֵר וְחוֹפֵן — חֲבֵירוֹ נִכְנָס בַּחֲפִינָתוֹ — דְּהָא מִקַּיְימָא חֲפִינָה. אִי אֵין חוֹפֵן וְחוֹזֵר וְחוֹפֵן — תִּבְּעֵי לָךְ.

The Gemara asks: What halakhic conclusion was reached about this matter? What in fact is the ruling in a situation where the High Priest took a handful of incense and then died? May the newly appointed High Priest use the handful that has already been scooped, or does he require a new handful? Rav Pappa said: The resolution of this question depends on a different problem. If the High Priest scoops the handful when he takes the incense from the coal pan, and again scoops a handful in the Holy of Holies, this would mean that another priest may enter with the handful of the first High Priest, as the mitzva of scooping the handful has been fulfilled. However, if the High Priest does not scoop and again scoop, let the dilemma be raised.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב הוּנָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב יְהוֹשֻׁעַ לְרַב פָּפָּא: אַדְּרַבָּה, אִי חוֹפֵן וְחוֹזֵר וְחוֹפֵן, לֹא יִכָּנֵס אַחֵר בַּחֲפִינָתוֹ — אִי אֶפְשָׁר שֶׁלֹּא יְחַסֵּר וְשֶׁלֹּא יוֹתִיר. וְאִי אֵין חוֹפֵן חוֹזֵר וְחוֹפֵן — תִּיבְּעֵי לָךְ.

Rav Huna, son of Rav Yehoshua, said to Rav Pappa: On the contrary, if the High Priest scoops and again scoops, another priest should not be permitted to enter with his handful, as it is impossible that the new handful will be neither less nor more than the amount of the first handful, which means the handful will not have been taken properly. But conversely, if he does not scoop and again scoop, let the dilemma be raised, as the mitzva of taking a handful has already been fulfilled by the first priest, and the second priest has merely to place the incense on the coals.

דְּאִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: חוֹפֵן חוֹזֵר וְחוֹפֵן, אוֹ לָא? תָּא שְׁמַע: כָּךְ הָיְתָה מִידָּתָהּ. מַאי לָאו: כְּשֵׁם שֶׁמִּדָּתָהּ מִבַּחוּץ כָּךְ מִדָּתָהּ מִבִּפְנִים!

The Gemara explains the background to this problem. As a dilemma was raised before the Sages: Does the High Priest scoop a handful from the incense once and again scoop a handful a second time in the Holy of Holies, or does he not scoop a second time? The Gemara suggests: Come and hear a resolution to this dilemma from the mishna: This was the measure of the spoon. What, is it not correct to infer from the mishna that just as its measure is on the outside, so is its measure on the inside, i.e., there is no need to scoop another handful, as this is its fixed measure that he pours onto the coal pan.

לָא, דִּילְמָא שֶׁאִם רָצָה לַעֲשׂוֹת מִדָּה — עוֹשֶׂה, אִי נָמֵי: שֶׁלֹּא יְחַסֵּר וְשֶׁלֹּא יוֹתִיר.

The Gemara rejects this suggestion: No, that is not necessarily the correct interpretation of the mishna. Perhaps it means that if he wants to measure a precise amount for his handful, he may measure with a utensil for this purpose. Alternatively, it could mean that he may take neither less nor more than the measure he initially took. Consequently, there is no proof from the mishna with regard to whether the High Priest must scoop a second handful.

תָּא שְׁמַע:

The Gemara further suggests: Come and hear a resolution to this dilemma from a baraita:

כֵּיצַד הוּא עוֹשֶׂה? אוֹחֵז אֶת הַבָּזֵךְ בְּרֹאשׁ אֶצְבְּעוֹתָיו, וְיֵשׁ אוֹמְרִים בְּשִׁינָּיו, וּמַעֲלֶה בְּגוּדָלוֹ עַד שֶׁמַּגַּעַת לְבֵין אַצִּילֵי יָדָיו, וְחוֹזֵר וּמַחְזִירָהּ לְתוֹךְ חׇפְנָיו, וְצוֹבְרָהּ, כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּהֵא עֲשָׁנָהּ שׁוֹהֶה לָבוֹא. וְיֵשׁ אוֹמְרִים: מְפַזְּרָהּ, כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּהֵא עֲשָׁנָהּ מְמַהֶרֶת לָבוֹא.

How should the High Priest act in the Holy of Holies, when he needs to place the incense on the coals by taking a handful from the spoon and placing it in his hands? After he places the coal pan on the ground, he holds the front of the ladle, i.e., the spoon of incense, with his fingertips, and some say he holds it with his teeth. At this stage the handle of the spoon rests between his arms. And he pushes it and raises it up slowly with his thumb toward his body until it reaches between his elbows, which he then uses to turn it over. He then returns the incense into his palms, after which he pours it from his hands into the coal pan. And he heaps the incense into a pile on the coals so that its smoke rises slowly. And some say he does the opposite, that he scatters it so that its smoke rises quickly.

וְזוֹ הִיא עֲבוֹדָה קָשָׁה שֶׁבַּמִּקְדָּשׁ. זוֹ הִיא וְתוּ לָא? וְהָא אִיכָּא מְלִיקָה! וְהָא אִיכָּא קְמִיצָה! אֶלָּא: זוֹ הִיא עֲבוֹדָה קָשָׁה מֵעֲבוֹדוֹת קָשׁוֹת שֶׁבַּמִּקְדָּשׁ. שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ: חוֹפֵן וְחוֹזֵר וְחוֹפֵן. שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ.

And this taking of a handful of incense is the most difficult sacrificial rite in the Temple. The Gemara asks: This one is the hardest rite, and no other? But there is pinching, which is also considered extremely difficult; and there is taking a handful of a meal-offering, another complex rite. Rather, this taking of a handful of incense is one of the most difficult rites in the Temple, rather than the single most difficult one. In any event, you can learn from this that the High Priest scoops a handful and again scoops. The Gemara concludes: Indeed, learn from this that it is so.

אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: שָׁחַט וָמֵת, מַה הוּא שֶׁיִּכָּנֵס אַחֵר בְּדָמוֹ? מִי אָמְרִינַן: ״בְּפַר״ — וַאֲפִילּוּ בְּדָמוֹ שֶׁל פַּר, אוֹ דִילְמָא: ״בְּפַר״ — וְלֹא בְּדָמוֹ שֶׁל פַּר.

§ A dilemma was raised before the Sages: If a High Priest slaughtered the bull and died, what is the halakha with regard to whether another High Priest may enter the Holy of Holies with the blood of the bull that his predecessor slaughtered? Do we say that the verse: “With this Aaron shall come into the sacred place, with a bull” (Leviticus 16:3) teaches that the priest must enter with the blood of a bull, but it need not necessarily be the blood of the bull he himself slaughtered, and in that case he may enter even with the blood of a bull slaughtered by someone else? Or perhaps the verse should be interpreted precisely: “With a bull,” and not with the blood of a bull slaughtered by another?

רַבִּי חֲנִינָא אוֹמֵר: ״בְּפַר״ — וְלֹא בְּדָמוֹ שֶׁל פַּר, וְרֵישׁ לָקִישׁ אָמַר: ״בְּפַר״ — וַאֲפִילּוּ בְּדָמוֹ שֶׁל פַּר. רַבִּי אַמֵּי אָמַר: ״בְּפַר״ — וְלֹא בְּדָמוֹ שֶׁל פַּר, רַבִּי יִצְחָק אָמַר: ״בְּפַר״ — וַאֲפִילּוּ בְּדָמוֹ שֶׁל פַּר.

The Sages disputed this matter. Rabbi Ḥanina says: “With a bull,” and not with the blood of a bull, which means that the newly appointed High Priest must slaughter another bull, as he can enter only with the blood of a bull he himself slaughtered. And Reish Lakish said: “With a bull,” and even with the blood of a bull. Likewise, Rabbi Ami said: “With a bull” and not with the blood of a bull; Rabbi Yitzḥak said: “With a bull,” and even with the blood of a bull.

אֵיתִיבֵיהּ רַבִּי אַמֵּי לְרַבִּי יִצְחָק נַפָּחָא: נִמְנִין וּמוֹשְׁכִין יְדֵיהֶן מִמֶּנּוּ עַד שֶׁיִּשָּׁחֵט, וְאִם אִיתָא — ״עַד שֶׁיִּזְרוֹק״ מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ!

Rabbi Ami raised an objection to Rabbi Yitzḥak Nappaḥa, the smith: To join a group of people who arranged to partake together of a single Paschal offering, individuals may register as part of a group and they may withdraw from it and join another group until the offering is slaughtered. And if it is so, that the blood of an animal is considered part of the offering, this tanna who authored this statement should have said that they may withdraw until the blood is sprinkled. If, as you maintain, the blood of an offering is part of the offering itself, why can’t a person register to or withdraw from a group of a Paschal offering until its blood is sprinkled?

שָׁנֵי הָתָם, דִּכְתִיב: ״מִהְיוֹת מִשֶּׂה״ — מֵחַיּוּתֵהּ דְּשֶׂה.

He answered him: It is different there, as it is written: “And if the household is too small for a lamb [mehiyot miseh], he and his neighbor who is next to his house” (Exodus 12:4). The phrase “mehiyot miseh” is read as meiḥiyutei deseh, from the life of a lamb. In other words, one can withdraw from a group only as long as the lamb is alive. If so, its blood is not considered part of the Paschal lamb by a special decree of the Torah, which does not apply to Yom Kippur.

מֵתִיב מָר זוּטְרָא: וְאֵין פּוֹדִין — לֹא בָּעֵגֶל וְלֹא בְּחַיָּה וְלֹא בִּשְׁחוּטָה וְלֹא בִּטְרֵיפָה וְלֹא בְּכִלְאַיִם וְלֹא בְּכוֹי, אֶלָּא בְּשֶׂה. שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּיָלֵיף ״שֶׂה״ ״שֶׂה״ מִפֶּסַח.

Mar Zutra raised an objection: And one may not redeem a male firstborn donkey with a calf, nor with an undomesticated animal, nor with a slaughtered lamb, nor with an animal with a condition that will cause it to die within twelve months [tereifa], nor with the product of the prohibited crossbreeding of a lamb and a goat, nor with a koy, a kosher animal with characteristics of both a domesticated animal and a non-domesticated animal, but with a lamb. This proves that a slaughtered animal is not considered a lamb. The Gemara rejects this claim: It is different there, as that tanna derives a verbal analogy of “lamb” (Exodus 13:13) and “lamb” (Exodus 12:4) from the Paschal offering: Just as a slaughtered lamb cannot be used for a Paschal offering, the same applies to the case of a firstborn donkey.

אִי מָה לְהַלָּן זָכָר תָּם וּבֶן שָׁנָה, אַף כָּאן זָכָר תָּם וּבֶן שָׁנָה? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״תִּפְדֶּה״ ״תִּפְדֶּה״ רִיבָּה.

The Gemara asks: If so, just as there, the Paschal offering must be male, unblemished, and a year old, so too here, for the redemption of a firstborn donkey, one should be obligated to use a male that is unblemished and a year old. Therefore the verse states: “And every firstborn of a donkey you shall redeem with a lamb; and if you shall not redeem it, then you shall break its neck” (Exodus 13:13). The repetition of: “You shall redeem,” “you shall not redeem,” serves to amplify the definition of the offering and include other animals as acceptable for this redemption, not merely those fit for the Paschal offering.

אִי ״תִּפְדֶּה״ ״תִּפְדֶּה״ רִיבָּה, אֲפִילּוּ כּוּלְּהוּ נָמֵי! אִם כֵּן, ״שֶׂה״ מַאי אַהֲנִי לֵיהּ?

The Gemara asks: If the phrases “You shall redeem” “you shall redeem” serve to amplify, even all animals should also be fit for the redemption of a firstborn donkey, including a calf, undomesticated beast, a slaughtered animal, and the other exceptions listed above. The Gemara answers: If so, what purpose does the verbal analogy of “lamb” serve? Rather, it is evident that certain animals are included while others are excluded. In any case, it is clear that the halakha of the blood of the bull on Yom Kippur cannot be derived from here.