Having a few chickens in your backyard has become trendy, especially among young hipster types in cities in the United States. However, this trend would not have caught on in Second Temple period Jerusalem. Among what we might call the zoning laws at the end of chapter seven of Bava Kamma, we have this rule:

“One may not raise chickens in Jerusalem, due to the sacrificial meat” (Bava Kamma 79b)

Chickens were a very common part of the average household in ancient Israel. They provided eggs and, eventually, dinner. But they were known for mischief and for poking around and breaking things. That is the ostensible reason why they were not allowed in Jerusalem. A chicken will root through garbage looking for food and may produce something unclean, like one of the seven impure creatures (שרצים). Then it might take that impure object and bring it somewhere where it will defile holy food, like meat from the sacrifices. In a city whose population included many priests, and where many visitors ate from their sacrifices, this could cause trouble.

Rbreidbrown, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

According to Professor Zeev Safrai (Mishnat Eretz Yisrael), this fear was not very realistic. Chickens were kept in their respective owners’ yards and so they did not wander around pecking at garbage heaps or graves. Even if they found something impure, it was likely to be miniscule and not of the requisite size to defile food. He claims that this law was meant to preserve a utopian ideal, to create the highest possible level of purity in the holiest of cities. It was not meant as a practical precaution.

Chickens were domesticated in our region at least four thousand years ago. We have depictions of them on two seal impressions from the seventh century BCE, where they seem to be ready to fight – we know cockfighting was a sport in ancient times. By the Second Temple period they were widely used for food and the Mishnah and Gemara are replete with mentions of them. Chickens today are probably the quintessential Jewish meat. We don’t eat pig, and cow is large and expensive. Go to many Jewish households on Shabbat and a roast chicken, as well as chicken soup, will grace the table. And yet, chickens do not appear in the Bible and they are not brought as sacrifices – that honor goes to pigeons and doves (יונה, תור). Professor Zohar Amar suggests a reason for this. The rabbis’ descriptions of chickens and roosters show that they were not considered particularly pleasant creatures. The chicken is described as עז, brazen (Beitzah 25b) as well as promiscuous and dirty. So while it may have been tasty (Rabbi Yohanan describes it as the king of birds in Bava Metzia 86b) it may have been considered unfit for the Temple, a place of peace and cleanliness.

While our Mishnah only mentions chickens in connection to Jerusalem, a Baraita a few pages later lists other restrictions on Jerusalem homeowners:

“Ten matters were stated with regard to Jerusalem: . . and one may not establish garbage dumps in Jerusalem; and one may not build kilns in it; and one may not plant gardens and orchards [pardesot] in it, except for the rose gardens that were already there from the times of the early prophets; and one may not raise chickens in it; . .” (Bava Kamma 82b)

Jerusalem is the holiest city. But despite its growth in Second Temple times, it was not a particularly large or spacious city. It was filled with residences, institutional buildings and narrow streets that led from one place to another. It did not have much in the way of open spaces. That, combined with the need to keep it holy and clean, kept agriculture out of the city. In addition, many residents were not farmers, unlike in the rest of the country (or the ancient world for that matter). Jerusalem’s population included many priests and Levites who served in the Temple plus government functionaries and teachers, just as it does today. But Jerusalem had a huge need for agriculture. Besides its many residents, visitors at peak times probably doubled the population. And the Temple was a large consumer of agriculture, from birds and animals for sacrifices to grain, oil and wine to accompany the offerings. Where did all that food come from?

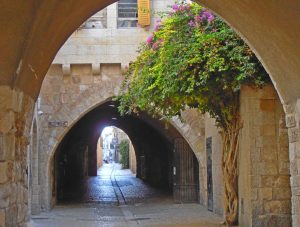

A contemporary Jerusalem alley

ekeidar, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The solution to Jerusalem’s food problem came from the surrounding villages. The city had two rings around it. The first was a ring of graves, since Jews did not permit burial within the city. Burial caves were located in and above the valleys around the city (the Kidron and the Hinnom Valleys) as well as north of the city (the area near the Damascus Gate of today and on Mount Scopus). These were close by so that people could bury their dead easily and conveniently.

Ancient burial cave behind the King David hotel

Alistair from Montreal, Canada, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The second ring, which is slowly being revealed to us by archaeology, was a ring of farming villages about five kilometers outside Jerusalem. Today we know about such villages in the (current Jerusalem) neighborhoods of Ramat Rachel (south of the city), Givat Ram (west), Ein Karem (west), Bethany and Issawiya (east) and more. A few years ago such a village was discovered in the Arab neighborhood of Sharafat, near Gilo in the south. The economy of these villages was based on agriculture and sometimes they specialized in a particular product. For example, Ein Karem, which may have been called Bet HaKerem in ancient times, produced grapes and wine (a kerem is a vineyard).

Ancient winepress in Ein Karem

Ron Havilio, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Because the intended market for the produce was Jerusalem, either for the Temple, the priests or visitors, all of whom wanted to maintain their pure status, there were often ritual baths located near food production sites, so that wine and oil could be made in purity. The need for a working food supply chain from outside the city was emphasized in times of siege, when Jerusalem was cut off from its neighbors. In the Great Revolt, the wealthy of Jerusalem prepared storehouses of food, for just this eventuality, but the Zealots destroyed them, causing starvation and defeat (Gittin 56a)

Jerusalem, city of light, holiness, Godliness. . . but not of farmers.