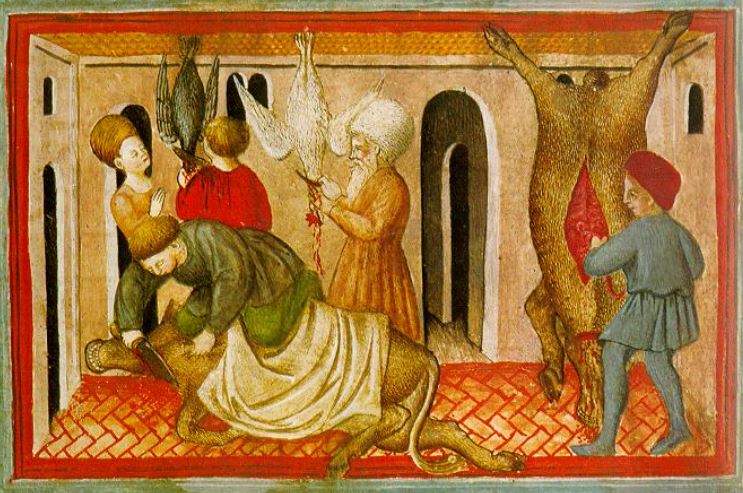

Zevachim is a very bloody masechet. Not in a metaphorical sense, like a murder mystery, but in the sense that we have spent a lot of time talking about blood – where it goes, what to do with the remains of it, and even how to launder it from the kohen’s robes. In our chapter of mixtures, the question is what to do about “good” blood that has been mixed up with “bad” blood:

“MISHNA: If the blood of unblemished offerings was mixed with the blood of blemished animals, the entire mixture shall be poured into the Temple drain.” (Zevachim 79b)

Putting the blood on the corners of the altar is the defining moment of a sacrifice, the one that ensures that it is accepted. What is so important about blood?

Blood is mentioned numerous times in the Torah – in connection with the sacrifices, as a metaphor for guilt (his blood shall be on his head) and repeatedly, as a dietary prohibition. The first time we hear about the ban on eating blood is when Noah emerges from the ark:

“You must not, however, eat flesh with its life-blood in it.” (Bereshit 9:4)

All people, not only Jews, are forbidden from eating a limb from a living animal, and hence its blood. This universal prohibition is echoed in the Torah, but here the emphasis is on the blood itself:

“And you must not consume any blood, either of bird or of animal, in any of your settlements” (VaYikra 7:26)

The Torah connects the prohibition of eating blood with the positive commandment of putting the blood on the altar. This is the blood paradox – it is forbidden to people but required to give to God:

“that the priest may dash the blood against the altar of God at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting . . .And if anyone of the house of Israel or of the strangers who reside among them partakes of any blood, I will set My face against the person who partakes of the blood; I will cut that person off from among kin” (VaYikra 17: 6, 10)

The blood is what creates the atonement:

“For the life of the flesh is in the blood, and I have assigned it to you for making expiation for your lives upon the altar; it is the blood, as life, that effects expiation.”

(VaYikra 17:1)

The two laws – forbidding human consumption of blood and commanding divine consumption – are a pair. As Nachmanides explains, God permitted people to eat meat after the flood, but only He could receive the blood because the blood is the essence of life:

“Thus He permitted man to use their [animals] bodies for his benefit and needs because their life was on account of man’s sake, and that their soul [i.e., blood] should be used for man’s atonement when offering them up before Him, blessed be He, but not to eat it, since one creature possessed of a soul is not to eat another creature with a soul, for all souls belong to God.” (Nachmanides to VaYikra 17:11)

Rashi also emphasizes that blood is life. He explains that the animal soul (nefesh, which is contained in the blood) will come and atone for the human soul that has sinned. The lifeblood can only be used by God and by symbolically giving it to Him by sprinkling it on the altar, we are asking Him to forgive our own souls.

That blood has power and is the source of life was not an unusual idea in the ancient Near East. What is unusual is that the Israelites (and all people, according to Bereshit) were forbidden from using it for themselves. Rather than using the blood in magic rituals or swallowing it to give them godlike powers, we were enjoined from any kind of blood consumption. Life is sacred and only God can receive the elemental force of life, blood.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Blood carries heavy symbolism in the Bible. Besides its use in sacrifices, we also see it in other roles in the Temple. It is used to purify the leper (Vayikra 14:6-7) and to consecrate the priests for work in the Temple (Shemot 29:20). It is also placed on the doorposts of the Israelites in Egypt to protect them (Shemot 12:13), although here it is not the blood itself which protects, but the courage of the Israelites in their defiance of the Egyptians (see here).

Perhaps most powerfully, blood is a sign of a covenant. Even today we use the term “blood brothers.” In some ancient cultures people would mix their blood to show that they were joined in an alliance. The people of Israel also symbolically exchange blood with their covenantal partner, God, at Mount Sinai:

“Moses took one part of the blood and put it in basins, and the other part of the blood he dashed against the altar . . . Moses took the blood and dashed it on the people and said, “This is the blood of the covenant that God now makes with you concerning all these commands.” (Shemot 24:6, 8)

Professor David Biale explains that this is covenant of blood is different than the standard idea that “blood is thicker than water.”

“The Israelites are a blood community here not because of the blood that flows in their veins but because of the blood that is on their bodies.” (The Blood Project)

This covenant is renewed every time we circumcise a Jewish baby boy. The “dam brit,” blood of the covenant, is a potent symbol of our commitment to God and the Torah (see here). The midrash explicates the verse in Ezekiel (16:6) that we say at every circumcision:

“and when the Holy One, blessed be He, passed over to plague the Egyptians, He saw the blood of the covenant of circumcision upon the lintel of their houses and the blood of the Paschal lamb, and He was filled with compassion on Israel, as it is said, When I passed by you and saw you wallowing in your blood, I said to you: ‘in your blood live! in your blood live!’ ” (Pirkei deRabbi Eliezer 29:12)

Instruments for a brit milah

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Blood played an outsize role in Temple worship, and the prohibition of blood continues to be prominent in Jewish life. Preparation of meat, checking eggs and removing the slightest hint of blood in food are prominent aspects of kashrut. This is why the blood libel, aimed at Jews from ancient times until today, is so patently absurd. Ahad haAm, the great Zionist writer of a century ago, explained this in words that can easily apply to contemporary blood libels against Israel in the last few years:

“Every Jew who has been brought up among Jews knows as an indisputable fact that throughout the length and breadth of Jewry there is not a single individual who drinks human blood for religious purposes…”But,” you ask, “is it possible that everybody can be wrong, and the Jews right?” Yes, it is possible: the blood accusation proves it possible” (Ahad haAm, “Hatzi Nechama”)