Learning the laws of courts and capital punishment, one might be forgiven for a small question lurking in the back of our minds – why do we need to know this? When is the last time a bet din had the power to execute someone? Not only the daf learner of today, but even the Amoraim in the Gemara asked this question:

“Rav Yosef said: Does one issue a halakha for the messianic period?” (Sanhedrin 51b)

Once we ask about the relevance of courts and capital punishment for our (their) time, we open the door to a host of other topics which at first glance seem irrelevant. And indeed that is Abaye’s response to his teacher’s question:

“Abaye said to him: If that is so, let us not teach all the halakhot of the slaughter of sacrificial animals, it is a halakha for the messianic period” (Sanhedrin 51b)

Which parts of the halachic system were still necessary and viable in a post Temple world, where most Jew were living outside of Eretz Yisrael? Laws connected to the life cycle (circumcision, marriage, divorce, death), food and some purity laws, Shabbat and holidays, prayer. But whole sections of Jewish law became impossible to keep and therefore (perhaps) unnecessary to learn. Among these categories: anything to do with the Temple, capital punishment, and laws about agriculture.

However, the Rabbis did not see it that way. Not only did they believe in keeping the memory of the Temple alive in all areas of Jewish life (see here), they believed in the concept of learning for its own sake:

“Rather, [one studies these halakhot due to the principle of] study Torah and receive reward” (Sanhedrin 51b)

By studying the commandments, we keep them alive until we can fulfill them. In the introduction to the Sefer Mitzvot Gadol (mid-13th century France) Rabbi Moses ben Jacob of Coucy states:

“Some of the people will say, what do these commandments about the Temple, the Land and purity have to do with me? They are not kept in this time. Do not say this! We need to know these commandments even if we do not keep them. . .” (Sefer Mitzvot Gadol, introduction to Mitzvot Aseh)

Rabbi Moses goes on to say that a mitzva has two components: learning and doing. Even if we are unable today to practice the laws connected to the Temple and the Land, we can still remember and study them.

The Rabbis take this idea a step further. Learning about a law can be the equivalent of keeping it! At the end of the tractate of Menachot, devoted to offerings given in the Temple, we have a whole page devoted to the concept that studying Torah is equal to bringing sacrifices:

“Rabbi Yitzḥak said: What is the meaning of that which is written: “This is the law of the sin offering” (Leviticus 6:18), and: “This is the law of the guilt offering” (Leviticus 7:1) That anyone who engages in studying the law of the sin offering it is as though he sacrificed a sin offering, and anyone who engages in studying the law of a guilt offering it is as though he sacrificed a guilt offering.” (Menachot 110a)

Preparing for the rebuilding of the Temple at the Temple Institute

פארוק, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Tosafot on our page and in a parallel Gemara in Zevachim (45a) go in a different direction. Rather than say that studying obsolete law equals keeping it, they look for the practical implications for today in those laws that seem outdated. For example, in Yoma (13a) we learn that if a high priest has to be replaced for the Yom Kippur service, he may return to serve afterwards in the Temple. Tosafot compares this to a community leader who is reinstated after having to leave his post for a time. Another example has to do with when we begin to say the prayer for rain (Taanit 4b). Even though one reason for delaying the prayer is no longer relevant – pilgrims do not need to return to Babylonia from the Temple – another is still applicable, that of the produce still growing in the fields.

At various times in Jewish history, false messiahs proclaimed that the end times were already here and therefore halacha has changed. They inverted the idea that we have in the Gemara – rather than the time of redemption being when we can return to keeping all the old laws, it became a time to cast aside halachot that they felt no longer applied in this new, enlightened age. A classic example is abolishing the fasts for commemorating the destruction of the Temple, something done by Shabbatai Tzvi in the seventeenth century. Perhaps to combat this idea, Maimonides at the end of the Mishneh Torah states:

“Do not presume that in the Messianic age any facet of the world’s nature will change or there will be innovations in the work of creation. Rather, the world will continue according to its pattern” (Mishneh Torah Kings and Wars 12:1)

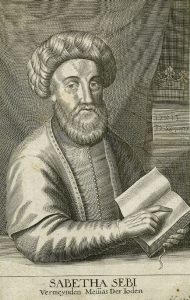

Shabbatai Tzvi

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A fascinating twist on the question of “Messianic halacha” is what has taken place in Israel in the last one hundred and fifty years. While Diaspora Jews had no ability to keep the complex halachot of shmita, teruma and maaserot, laws that apply only in the Land of Israel, Zionist pioneers did have to grapple with these issues. With the return to the Land in the nineteenth century, we have the first shmitta controversies. The conflict between wanting to follow the Torah laws (for the first time in centuries!) and needing to grow food to survive was particularly difficult in these early years. Today we have institutes dedicated to studying the laws of agriculture in Eretz Yisrael and scholars who try to figure out how to have a thriving economy while still remaining true to the spirit and letter of halacha.

The challenge of a modern State of Israel, where Jews are the rulers and not the subjects, is a formidable one in many ways. How do we remain true to Torah while having a functioning economy, an army that defends us even on Shabbat and hospitals and doctors that operate according to ethical Torah principles? Yet it is one of the enormous privileges of our time, a chance to see these laws return to their proper place in Jewish life.

Sign in a field in Israel stating that the owner is keeping the shmitta

Eliran t, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons