אמרי נהרדעי The Sages of Nehardea say. . . (Bava Kamma 70a)

Depending upon the circles you travel in, certain names have a huge impact. For a whole generation of Americans, it was Harvard, Yale and Princeton (not anymore). If you are a part of the Torah world, the names are different: Gush, Lakewood, Yeshiva University, Ponevezh. And if you are from old school European Torah scholars you have yet another set of names: Volozhin, Mir, Lublin.

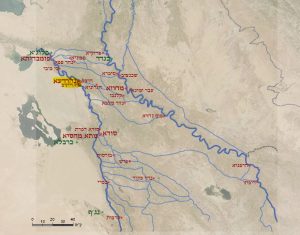

The Gemara also has institutions that inspire respect just from their names. In the Land of Israel they are Yavneh, Usha, Zippori and Tverya among others. The Babylonian names are Sura, Pumbedita, Mahoza but king of all of them is Nehardea. Some derive the town’s name from a combination of nehar – river and deah – knowledge, whether this etymology is correct or not, from Nehardea flowed the sources for the great Babylonian academies.

יהונתן, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The phrase “the Sages of Nehardea say” appears more than forty times in the Talmudic corpus, far more than similar phrases about other academies. Does it refer to a group of scholars or to the people of the town? There is a suggestion from a Gemara in Sanhedrin that it refers to one particular scholar Rav Hama, and his predecessors from Nehardea, Shmuel and Rav Nahman:

“The amora’im of Neharde’a, is referring to Rav Ḥama.” (Sanhedrin 17b)

Whether or not this is correct, it is interesting to understand the background to the yeshiva in Nehardea. As its name implies, Nehardea was located on the banks of the great river Euphrates. It also was next to a tributary, or more accurately a canal, called the Malka River, that connected the Euphrates to the Tigris. This made a good location great and the town was a prosperous one. We have several sources about the early Jewish community in Nehardea. Josephus tells us about it in his Antiquities of the Jews:

“There was a city in Babylonia, called Nehardea: not only a very populous one; but one that had a good and a large territory about it: and besides its other advantages full of men also. It was besides not easily to be assaulted by enemies, from the river Euphrates’s encompassing it all round; and from the walls that were built about it. . . For which reason the Jews, depending on the natural strength of these places, deposited in them that half shekel which every one, by the custom of our country, offers unto God. . .whence, at a proper time, they were transmitted to Jerusalem.” (Josephus Antiquities of the Jews 18:9:1)

A later source, the Letter of Rav Sherira Gaon, relates that Nehardea’s Jewish population was founded by exiles from Jerusalem in 597 BCE, the first exile of the Jews from that city. The refugees brought with them stones from Jerusalem with which they made the foundation of their synagogue, called Shef veYativ (moved and settled). This synagogue was famous in the Talmud for being a place where the Divine Presence rested and where rabbis congregated:

“the father of Shmuel and Levi were once sitting in the synagogue of Shef veYativ in Nehardea. The Divine Presence came and they heard a loud sound, so they arose and left.” (Megillah 29)

Nehardea remained an important Jewish center and Rabbi Akiva traveled there to intercalate the year (Mishnah Yevamot 16:7). The Exilarch had his seat there for a while, but only with the advent of the family of Shmuel did the town gain a yeshiva. Shmuel (3rd century CE) was a Nehardea patriot. He famously explained his knowledge of astronomy by saying that the paths of the stars are as well known to him as the paths of Nehardea (Berachot 58b). His yeshiva was known for its expertise in monetary law and civil suits. When Shmuel’s contemporary, Rav, returned from the Land of Israel, he came first to Nehardea but then struck out on his own to form his own yeshiva in Sura. The two schools became the pillars of Babylonian learning.

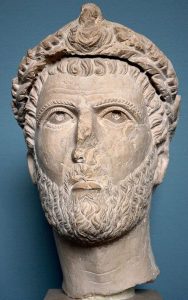

Shmuel’s yeshiva continued to thrive and after his death his student Rav Nahman took over. But then hard times came to Nehardea. As a wealthy city in a strategic location it was no stranger to armies passing through and even trying to conquer it. But in 260 a terrible blow came. Odaenathus, king of Palmyra, conquered the city with Roman support. This king, known as Ben Netzer, in Rabbinic sources, caused great destruction to the town and to the Jewish community.

Odaenathus,

Carole Raddato, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Rav Nahman left and eventually relocated to Machoza. He tried to reestablish the Nehardea yeshiva there but ultimately it was reincarnated in the Pumbedita yeshiva under Rav Yehuda’s auspices (for a story of the conflict between Rav Yehuda and Rav Nahman see https://hadran.org.il/author-post/order-in-the-court/). Nehardea never regained its prominence and indeed its dark side emerges here and there in the Gemara. There are questions about the lineage of the townspeople, partly because of the many military conquests, and presumably rape of the local women by the soldiers. These issues, along with the moving of the yeshiva and the conquest of the town, meant that physical Nehardea lost its place of importance in the Torah world.

But here is the extraordinary thing – years later, the “Sages of Nehardea” and the school of Nehardea are still being quoted, albeit in Pumbedita and Mahoza. The community of Nehardean exiles kept the name and reputation of their school and their teachers alive. A letter from the tenth century relates a tradition that in the yeshiva of Pumbedita the first three rows were occupied by “scholars of Nehardea,” a town that had been destroyed seven hundred years earlier!

Just as today there are people who study in the “Brisker way” long after the destruction of the Jewish community of Brisk, the Nehardeans kept the spirit and learning of their yeshiva alive for centuries. The pride the exiled scholars felt in their town and their school meant that one could say אמרי נהרדעי long after Nehardea was no longer.