A chance encounter in a public space has unintended consequences. A respected teacher is suspected of improper behavior. His name is cleared but he still feels guilty. Ripped from the headlines? No, a story in Masechet Avodah Zarah. Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus is accused of heresy and it seems it is because he was seen speaking to a min, a heretic:

“Rabbi Eliezer said to him: Akiva, you are right, as you have reminded me that once I was walking in the upper marketplace of Zippori, and I found a man who was one of the students of Jesus the Nazarene, and his name was Ya’akov of Kfar Sekhanya.” (Avodah Zarah 17a)

Who is the cast of characters in this tale and what is the setting? Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus (see here) needs little introduction. He was one of the greatest of the Tannaim of the Yavneh generation, student of Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai and teacher, along with Rabbi Yehoshua, of Rabbi Akiva. His name appears throughout the Mishnah and the Gemara. He was known to be very conservative in his views, never teaching anything that he had not heard himself from his teachers (Yoma 66), and one of the few Tannaim who followed the school of Shamai and not Hillel (Niddah 7b and Tosafot “Shamuti”).

His partner in conversation is well known too, albeit for negative reasons. Yaakov/Jacob/James (the Latin version of Jacob) of Kfar Sekhanya appears in other texts in the role of the Jewish Christian, or heretic (min in Hebrew). Most famously, he appears ten pages later in our masechet as a healer, forbidden by Rabbi Yishmael to help Rabbi Eliezer ben Dama:

“an incident involving ben Dama, son of Rabbi Yishmael’s sister, in which a snake bit him. And Ya’akov of Kfar Sekhanya came to treat him, but Rabbi Yishmael did not let him” (Avodah Zarah 27b)

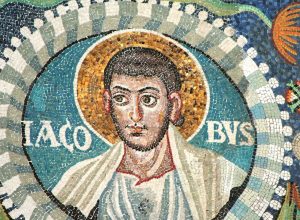

Can we identify Yaakov with anyone in early Christian history? Yaakov was a relatively common name in our period and in Jesus’ inner circle there are at least two, maybe three James. Two are apostles, students of Jesus: James the son of Zebedee (the Greater) and James the son of Alphaeus (the Lesser). There is also someone named James the Just. Is our Yaakov one of these or just a garden variety Jewish follower of Jesus? His position as a straw man for early Christianity in our sources would seem to argue that he is someone of importance.

James the Greater, Ravenna church sixth century

© José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro

Yaakov comes from Sekhanya, or as we call it today, Sakhnin. This was an ancient town in the lower Galilee, not far from Zippori. It was known for having a strong Jewish community. Rabbi Hanina ben Teradion, Bruria’s father, taught in Sekhanya; another sage from there was Rabbi Yehoshua of Sikhnin.

Modern day Sakhnin

מואפק חלאילה, CC BY 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons

The story takes place in the marketplace of Zippori (other versions of the story say the main street). Zippori had a strong Jewish community and among its luminaries were Rabbi Halafta, Rabbi Hanina and Rabbi Judah the Prince. However, it also had a strong pagan, and eventually Christian, presence. In addition, its thriving marketplace was patrolled by Roman soldiers and often visited by Roman tax collectors:

“Rabbi Yitzḥak said: there is not a single Festival on which troops did not come to Tzippori” [to conduct searches or to collect taxes] (Shabbat 145b)

The main street of ancient Zippori

Yair Haklai, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

This cosmopolitan scene lends itself to our story. Unlike a small provincial town, in Zippori you could and would encounter all types of people.

Finally, what is the time period in which our story takes place? Rabbi Eliezer is prominent in the generation of the destruction of the Temple and afterwards; the late first century CE. The Jewish community was rebuilding itself after the cataclysm of the Great Revolt, and had not yet been devastated by the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Christianity was just beginning and most Christians were Jews who also believed in Jesus. The communities were mixed. Christianity was outlawed by the Romans, and Christians were persecuted for their faith. Roman soldiers were everywhere.

Jews opposed this new phenomenon of Christianity as well. They labelled the early Christians “minim,” heretics, and established the Birkat HaMinim in the amida in order to make Jewish Christians uncomfortable in synagogues. But as we see from our story, it was not always easy to identify the heretics.

Let’s take a closer look at the “Torah” that Yaakov taught Rabbi Eliezer and try to understand it.

“He said to me: It is written in your Torah: ‘You shall not bring the payment to a prostitute, or the price of a dog, into the house of the Lord your God’ (Deuteronomy 23:19). What is the halakha: Is it permitted to make from the payment to a prostitute for services rendered a toilet for a High Priest in the Temple? And I said nothing to him in response. He said to me: Jesus the Nazarene taught me the following: It is permitted, as derived from the verse: ‘For of the payment to a prostitute she has gathered them, and to the payment to a prostitute they shall return’ (Micah 1:7). Since the coins came from a place of filth, let them go to a place of filth” (Avodah Zarah 17a)

Yaakov asked the rabbi a seemingly legal question – can a commodity that a prostitute earns be used for something non-sacred, in fact the most profane thing in the Temple, a toilet? He answered his own question in a classic Rabbinic way by using a Biblical verse – money that came from something dirty can be returned to something dirty. What are we to make of this odd rhetorical question?

Rabbi Benjamin Lau sees the story as playing both on Rabbi Eliezer’s asceticism and Christianity’s inclination to separate the physical and the spiritual. As a follower of Shamai, Rabbi Eliezer saw bodily functions as necessary but not elevated, as we can see in Hillel and Shamai’s different takes on physicality:

“When Hillel went somewhere, they would say to him ‘Where are you going?’ ’To do a mitzvah.’ ‘What mitzvah Hillel?’ ‘I am going to the toilet!’ ‘And is that a mitzvah?’ He said to them, ‘Certainly, so that one’s body should not be damaged’ . . .Shamai did not say this, but rather, ‘Let a person perform his duties with this body.’”(Avot deRabbi Natan B, 30)

Christianity took this idea to the extreme and advocated asceticism and even celibacy if possible. Perhaps Yaakov is trying to lure Rabbi Eliezer to the Jewish Christian world with this coded polemic against prostitution, physicality and the Temple. Rabbi Eliezer admits that he enjoyed this teaching.

A very different approach is taken by Shlomy Raiskin in an article in the Mamakim journal (1998). He sees the conversation not as proselytizing for Christianity but as a coded polemic against the Roman empire. Vespasian, the emperor in Rabbi Eliezer’s time, famously collected a tax from the urine in public urinals (urine had many useful functions in the ancient world). This money, along with a tax on prostitution, was used to build the Colosseum. Raskin explains that the Roman emperor was also called the Pontifex Maximus, the Great Priest, or the High Priest as we would say in Hebrew. Yaakov is making fun of the Romans, who use earnings from the bathroom and prostitution to fund the projects of the “High Priest.” And why say this in code? Because Roman soldiers are everywhere in Zippori. Rabbi Eliezer, as a Jew who has suffered under the Romans, appreciates the joke.

Both explanations seem valid when we read Rabbi Eliezer’s reaction to the story:

“ ‘Remove your way far from her,’ this is a reference to heresy; ‘and do not come near the entrance of her house,’ this is a reference to the ruling authority.” (Avodah Zarah 17a)

Fittingly, the verse Rabbi Eliezer chooses for this lesson refers to prostitution, thereby riffing on Yaakov’s teaching.

However we interpret this story, one thing is clear. In late first century Galilee, the line between Rabbinic Jews and Jewish followers of Jesus was blurry. They lived together, shopped together and had conversations about Torah. A century or so later, the two groups would be much more separate and the Rabbinic need to create distance would be unnecessary.

Medieval depiction of the Church and the Synagogue, Ecclesia and Synagoga

Sodabottle, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons