“Rav Ḥiyya bar Ashi said: Many times I would stand before Rav and place water on his shoes,” (Zevachim 94a)

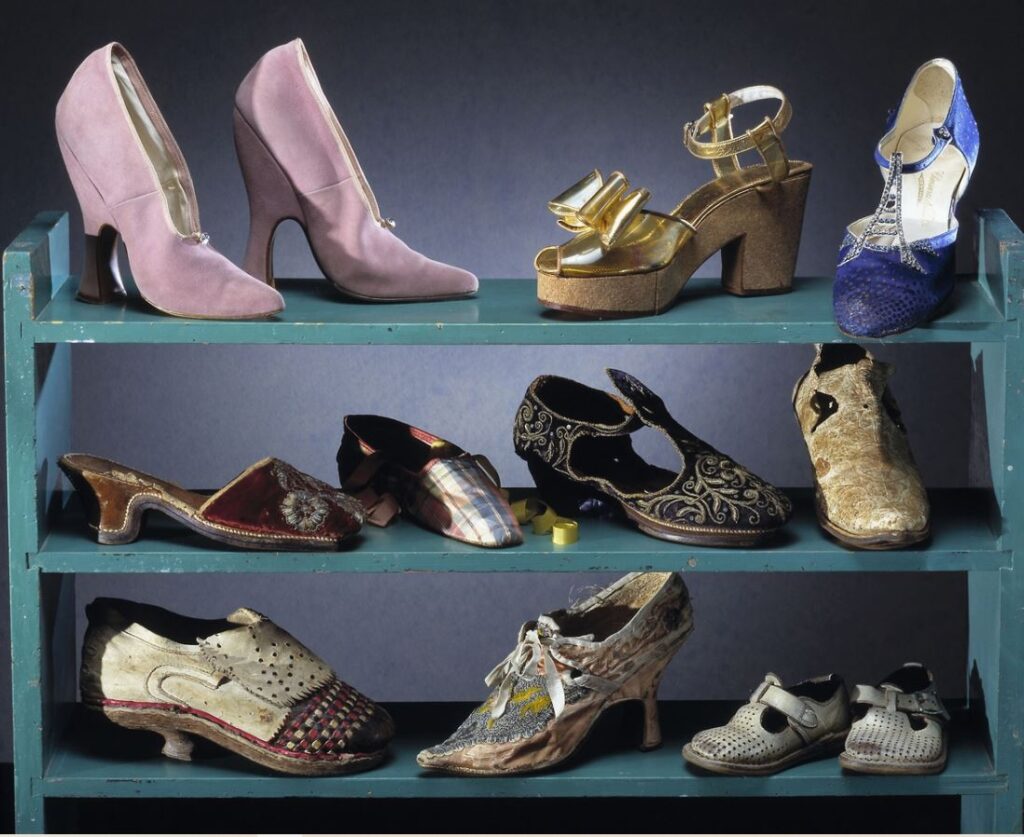

Maybe you have an Imelda Marcos-like shoe closet or maybe you just wear your trusty sneakers. Either way, most of us wear shoes all the time. But do shoes have a deeper meaning in Judaism? Let’s take a look at some sources about footwear in the Bible and in Rabbinic literature.

Shoes are a basic item, one that it is hard to do without, especially in a cold or wet climate. The Rabbis emphasized this idea:

“Rav Yehuda said that Rav said: One should always sell the beams of his house and purchase shoes for his feet” (Shabbat 129a)

Rashi adds that the reason to always have shoes is that there is nothing more degrading than walking barefoot in public spaces. Yet despite the necessity of shoes and their importance, they are considered a small and marginal item. When the King of Sdom offers all the spoils to Abraham after he frees the king’s prisoners, Abraham will not deign to accept anything. He emphasizes that he won’t take even the least important item from Sdom:

“I will not take so much as a thread or a sandal strap of what is yours; you shall not say, ‘It is I who made Abram rich’ “ (Bereshit 14:23)

The insignificance and relative cheapness of shoes are again used by the prophet Amos to show that Israelite judges were easily bribed and would sell out the poor for a small payment: a pair of shoes.

“Thus said GOD:

For three transgressions of Israel,

For four, I will not revoke the decree:

Because they have sold for silver

Those whose cause was just,

And the needy for a pair of sandals.” (Amos 2:6)

While most shoes were ubiquitous and inexpensive, others were status symbols, as they are today. Roman statues often use footwear to indicate importance and rank. Servants (if they appeared in statues or pictures at all) were barefoot. Emperors wore calcei, closed laced shoes that were meant for the nobility. Soldiers were depicted with caligae, nailed sandals, fit for battle. The most unusual were the gods. While some gods did have special shoes, like Hermes and his winged sandals, others were depicted barefoot. This was for a very different reason than the servants. While they were too poor to afford shoes, the divine gods did not need the mundane protection of shoes.

Shoes found at the ancient Roman site of Vindolanda in England

Victuallers, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Shoes were absolutely necessary for a long journey, and so the Israelites were commanded to eat their Passover sacrifice with their shoes on:

“This is how you shall eat it: your loins girded, your sandals on your feet, and your staff in your hand; and you shall eat it hurriedly: it is a Passover offering to the LORD.” (Shmot 12:11)

Rabbi Yirmiya’s instructions on his deathbed were meant to prepare him for a different kind of journey:

“Rabbi Yirmiya commanded: Dress me in clean white, dress me in my socks, put my shoes on my feet and a walking stick in my hand, lay me on my side, when the Messiah comes I shall be ready” (Yerushalmi Kilayim 9:3)

Like everything else in life, shoes are provided by God and He needs to be thanked for them:

“Upon putting on his shoes, one should recite: Blessed…Who has provided me with all I need,” (Berachot 60b)

Shoes provide essential protection from the elements and thus symbolize our connection to this material life. In order to approach the Divine, shoes must be removed, as Moses is commanded when he sees the burning bush:

“And He said, “Do not come closer. Remove your sandals from your feet, for the place on which you stand is holy ground.” (Shmot 3:5)

Similarly, one cannot step on the holy areas of the Temple Mount with shoes and the priests have to serve in the Temple barefoot:

“One may neither enter the Temple Mount with his staff in his hand, nor with his shoes on his feet, nor with money tied in his cloth and with his money-belt slung behind him” (Brachot 62b)

Since taking off your shoes means you are disconnecting from the world, it makes sense that going barefoot is also a sign of mourning. This is illustrated in the Bible when David flees Jerusalem:

“David meanwhile went up the slope of the [Mount of] Olives, weeping as he went; his head was covered and he walked barefoot.” (Samuel II 15:30)

The Rabbis codified this in halacha, both for a mourner (Moed Katan 15b) as well as on fast days like Tisha B’Av and Yom Kippur (Mishnah Yoma 8:1).

Perhaps the most famous shoe in the Torah is that of the man who refuses to marry his brother’s childless wife. He has to take part in a ceremony where he takes his shoe off and she spits in his face. The ceremony itself is called chalitza, the taking off of shoes:

“his brother’s widow shall go up to him in the presence of the elders, pull the sandal off his foot, spit in his face, and make this declaration: Thus shall be done to the man who will not build up his brother’s house! And he shall go in Israel by the name of ‘the family of the unsandaled one.’ ” (Devarim 25:9-10)

While the text implies that the use of the shoe is to humiliate the man who won’t do his duty by his family, Rabbenu Bahya offers a different explanation. If the brother were to marry the widow and have a child, that would keep his dead brother alive. Since he refuses to do that, he is now formally showing that his brother is dead and so he has to mourn, by taking off his shoe as mourners do.

Halitza shoe

LGJMS, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Shoes have been found in archaeological excavations all over the ancient world. Here in Israel sandals were found in the desert, in the Qumran community of ascetics as well as in the rebel stronghold of Masada. We have even found Roman soldier’s nailed sandals.

Sandals found in the Bar Kokhba cave hideout in Nahal Hever

Chamberi, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Shoes were a common item that made their wearer, even if he or she was poor, feel human and not on the level of animals, as we see in this statement:

“He said to him: One who rides on a horse is a king. One who rides on a donkey is a free man. And one who wears shoes is at least a human being.” (Shabbat 152a)

Heels or flats, boots or sandals, shoes make the (wo)man.

Nordic Museum, CC BY 3.0 NO <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/no/deed.en>, via Wikimedia Commons