It’s Elul, time for those new year resolutions. But what many of us forget is that it is hard to keep up with the new and improved you. Maybe that is why the custom has evolved to take on certain more restrictive laws only in Elul or only in the ten days between Rosh haShana and Yom Kippur. Maybe I cannot be careful all year about eating bread baked by non-Jews, but at least I can do it for ten days.

Having trouble keeping more restrictive laws is something that the rabbis were well aware of. In addition to enacting many gezerot, rules that are meant to safeguard us from violating Torah law, they formulated an important principle that appears here in Horayot, as well as in several other places in the Gemara:

“Our Sages relied on the statement of Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel and on the statement of Rabbi Elazar, son of Rabbi Tzadok, who would say: One does not issue a decree (gezera) upon the congregation unless the majority of the congregation is able to withstand it.” (Horayot 3b)

This axiom is modified slightly in the Yerushalmi, where the focus is more on people’s willingness to keep the decree, rather than their ability:

“any restrictive decree passed by a court which is not accepted by the majority of the public is not a decree” (Yerushalmi Avodah Zarah 2:8)

Maimonides explains that if the people cannot live up to the gezera, it is not valid.

“If a court issued a decree, thinking that the majority of the community could uphold it and after the decree was issued, the majority of the community raised contentions and the practice did not spread throughout the majority of the community, the decree is nullified.” (Mishneh Torah Hilchot Mamrim 2:6)

Of course, this only applies to Rabbinic injunctions meant to protect the Torah law, not to Torah itself.

What are some cases where this principle has been applied? The Mishnah in Bava Kamma tells us that it is forbidden to raise small animals (בהמה דקה), meaning sheep and goats, in the Land of Israel. The Gemara adds that while this is true, large animals (cows) can be raised here because not doing so would be too difficult for farmers. They would not be able to import all the oxen they need for working the land. Interestingly, the Gemara limits the restriction on small animals as well:

“But one may raise them in the forests of Eretz Yisrael . . . one may raise them in the wilderness that is in Judea and in the wilderness that is on the border near Akko.” (Bava Kamma 79b)

Professor Zeev Safrai believes that the law against raising goats is a utopian law, an ideal that could not be kept in real life. Goats and sheep were a large part of the economy of the Land of Israel. While the Gemara acknowledges that people could not live with a rule against large animals, perhaps in reality they did not follow the law about small ones either.

Goats in Carmel forest

אילן קוסטיקה, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons

In a different situation, we see that decrees were annulled when it was seen that people were not keeping them. This is the case with Gentile oil. In the list of things made by Gentiles that Jews cannot eat, oil is featured (Avodah Zarah 35b). The Gemara discusses how this was a gezera from the time of Daniel but Rabbi Judah Nesia (Rebbe’s grandson, circa 220 CE) revoked this rule. He was (perhaps) criticized for this by his own student, Rabbi Simlai:

“Rabbi Yehuda Nesia was traveling while leaning upon the shoulder of Rabbi Simlai, his attendant. Rabbi Yehuda Nesia said to him: Simlai, you were not in the study hall last night when we permitted the oil of gentiles. Rabbi Simlai said to him: In our days, you will permit bread of gentiles as well.” (Avodah Zarah 37a)

Maresha oil press, with a niche for an idol

I, Chai, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

The Bavli does not explain why the oil decree was so hard to keep, only that the rabbis noticed that it was not being kept: But was it universally not observed? Josephus tells two fascinating mini-stories about Gentile oil; in both of which it seems that the Jews were very careful about not using it, even as they were less stringent on other matters. In Antiquities of the Jews he writes that the Jews in the Diaspora refused to use Gentile oil in the gymnasium, so instead of receiving free oil, like the other participants, they got a sum of money:

“An argument for which you have in this, that whereas the Jews do not make use of oil prepared by foreigners, they receive a certain sum of money from the proper officers belonging to their exercises, as the value of that oil” (Antiquities 12:3)

Joining the games in the gymnasium was considered fine, while Gentile oil was prohibited – interesting priorities, and ones that contradict our Gemara. In addition, Josephus tells us that during the Great Revolt one of the Jewish rebel leaders made sure that the Jews in the north (Panias) received kosher oil, since they could not use Gentile oil:

“For he said, that those Jews who inhabited Caesarea Philippi, and were shut up by the order of the King’s deputy there, had sent to him to desire him, that, since they had no oil that was pure for their use, he would provide a sufficient quantity of such oil for them: lest they should be forced to make use of oil that came from the Greeks, and thereby transgress their own laws.” (Life 13)

While animals and oil are very practical decrees, connected to the economy and to Jews mixing in Gentile society, our final example relates to a more spiritual concern. After the Temple was destroyed, the rabbis encouraged restraint, knowing that the people would not be able to continue the difficult practices they wanted to impose upon themselves:

“When the Temple was destroyed a second time, there was an increase in the ascetics among the Jews, to not eat meat and to not drink wine. Rabbi Yehoshua . . said to them: My children, for what reason do you not eat meat and do you not drink wine? They said to him: Shall we eat meat, from which offerings are sacrificed upon the altar, and now the altar has ceased to exist? Shall we drink wine, which is poured as a libation upon the altar, and now the altar has ceased to exist?”

Rabbi Yehoshua challenges the ascetics and says that according to their logic, bread, fruit and even water should be forbidden, since all of these were used in the Temple. Finally, he gently explains to them:

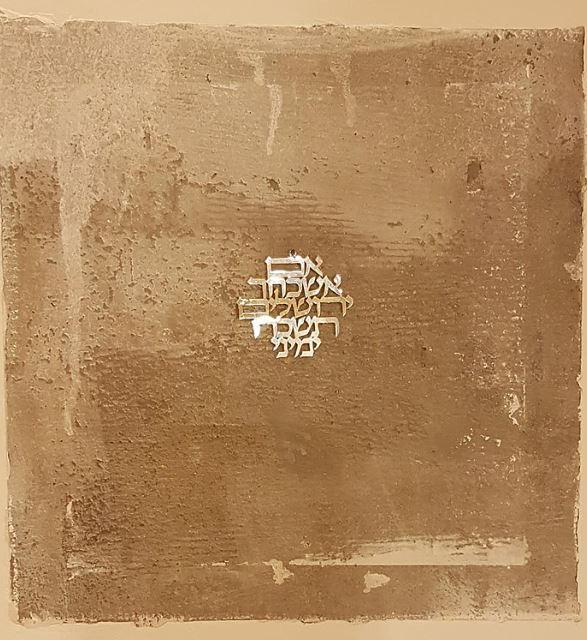

“Rabbi Yehoshua said to them: My children, come, and I will tell you. To not mourn at all is impossible, as the decree was already issued. But to mourn excessively is also impossible, as the Sages do not issue a decree upon the public unless a majority of the public is able to abide by it , . . Rather, this is what the Sages said: A person may plaster his house with plaster, but he must leave over a small amount in it. . .” (Bava Batra 60b)

The Rabbis were concerned with the law but they also displayed a deep understanding of psychology. They used their awareness of human flaws as a way to encourage a better and more holy life for all Jews.

Yehud830, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons