An open pit in a public space would normally be considered a menace, the epitomy of the concept of בור. And yet on our daf we have a figure who goes around opening pits and he is considered a righteous man:

“And this was the practice of Neḥunya the digger of pits, ditches, and caves, who would dig, open, and transfer them to the public. When the Sages heard about the matter, they said: He has fulfilled this halakha.” (Bava Kamma 50a)

Why was Nehunya praised for his actions? Because he would give his pits and cisterns over to the public and people would have water to drink.

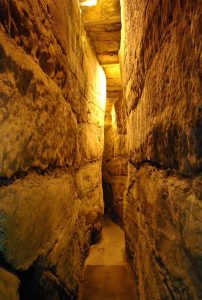

Water is an essential commodity for any functioning society. Issues of water rights and technology to obtain clean water are still front-page news in the twenty-first century, how much more so in ancient times. Every household in our dry land worried about water and made sure to have private water-collecting cisterns on their property. But cities, and certainly large and popular cities like Second-Temple era Jerusalem, also needed to provide water for their institutions and their visitors. The Temple was a huge consumer of water. There was a need for drinking water but also to fill the purifying mikvaot, to pour out on the altar, and to cleanse the complex of the vast amounts of blood that flowed there. Excavations of the Western Wall Tunnels in the last few decades have uncovered cisterns, ritual baths and even fountains that were located alongside the main street of Jerusalem two-thousand years ago.

A guardrail protecting a cistern in the Western Wall Tunnels

Chana Koren

In addition, with the massive pilgrimages that Jerusalem experienced (scholars estimate that the population of the city doubled at holiday times), the city needed water to quench the thirst of visitors. The Siloam (Shiloach) pool fed by the Gihon spring was impressive and a stopping points for visitors to Jerusalem but it could not serve the needs of all the thirsty sojourners. That is why rulers of the city in Second Temple times, starting with the Hasmoneans and continuing under Herod, built aqueducts and pools to bring water to Jerusalem from springs further south. Remains of these aqueducts still exist today both in the New City (by the Haas Promenade) and in the Old (in the Western Wall Tunnels).

The Hasmonean aqueduct north of the Temple Mount

Berthold Werner, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Besides these large-scale projects, there were more modest efforts to provide water. Our sources tell us about a wealthy individual who troubled himself to provide water for pilgrims. This is the famous story of Nakdimon ben Gurion who saw that Jerusalem’s visitors did not have enough water and arranged to “borrow” water from a Gentile ruler, in the hopes that God would refill the cisterns with rain in time to repay his debt. (Taanit 19b-20a).

But who dug those cisterns to begin with? Here is where the diggers like Nehunya come in. While the beginning of the Mishnah in Shekalim ensures us that the rabbis were tasked with providing water for the pilgrims:

“And on the fifteenth day of the month of Adar, . . they also repair the roads, and the streets, and the cisterns.” (Mishnah Shekalim 1:1)

it does not tell us who really did the work. But if we look a few chapters later in Masechet Shekalim we find a list of “professional” workers and contractors in the Temple:

“These are the officials who served in specific positions in the Temple: Yoḥanan ben Pineḥas was responsible for the seals Aḥiyya was responsible for the libations, Matya ben Shmuel was responsible for the lotteries,. Neḥunya was the well digger. . .” (Mishnah Shekalim 5:1)

Who are these people? The Second Temple stood for centuries, surely there was more than one person responsible for these jobs over that span of time. The Yerushalmi commentary on the Mishnah suggests two possibilities: these are the people who held these jobs when the Mishnah was created, or these are the “all-stars,” the ones who did their job best over time, and so they are remembered.

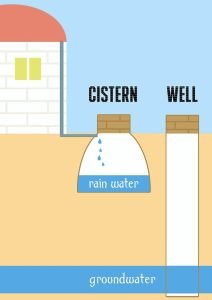

Each of these professional jobs is interesting but we will focus on Nehunya. According to our source in Bava Kamma, he seems to have dug the ditches not as a job but on his own initiative, and then he handed them over to the public. He is mentioned here as a digger of ditches, שיחין. The Mishnah and Gemara often group together three similar, but different categories: בורות שיחין ומערות, cisterns, ditches and caves. For our purposes, they are all spaces where water can be collected, albeit of different sizes and shapes.

It seems that Nehunya did not just dig pits that then filled with rainwater, he also sought out underground sources of water, as the Yerushalmi in Shekalim explains:

“He was digging ditches and caves and knew which rock has water and which rock has cracks and how far the cracks extended.” (Yerushalmi Shekalim 5:1)

This would make Nehunya not just a manual laborer but someone with the skill of finding water in an arid landscape. In the old days this was called a water diviner or a dowser and it was thought to be an almost magical ability. Today we know that water can be found if you look for geological and topographical clues, which seems to be what Nehunya was doing.

תמר הירדני Tamar Hayardeni, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Modern Israel also has a dire need for water. One of the more recent “Nehunyas” was a man named Simcha Blass (1897-1982), the premier water engineer in the pre-State Yishuv and one of the founders, along with Levi Eshkol and Pinchas Sapir, of Mekorot, the State of Israel’s water company. Blass was one of the innovators behind the National Water Carrier, a huge project in Israel’s first decade to bring water from the north to the center and south of the country. In addition, along with his son, he invented the drip irrigation system which fuels Israeli agriculture and has been exported all over the world.

Button drip irrigation system

Borisshin, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

But in 1947 Blass was involved in a smaller scale but vital project – bringing water to the Negev and the new settlements that were being built there. He found a good source of water by Nir Am, in the Northern Negev, and laid two pipelines, a total of more than two hundred kilometers, to reach the eleven new Negev settlements that had been founded in 1946. Blass’ pipeline allowed these communities to survive and these facts on the ground pushed the United Nations to include the Negev in their plan for a Jewish State.

The eleven new communities (in red)

Tamar Hayardeni, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons

Nehunya then and Nehunya now – quenching Jewish thirst and settling the land!