As we are nearing the end of Masechet Zevachim, the Gemara describes places for sacrifices that were used before the building of the Temple in Jerusalem. The lengthy Mishnah on daf 112b tells us what was allowed at the various holy sites, and what wasn’t:

“And from the time that the Tabernacle was established, private altars were prohibited and the sacrificial service was performed by the priests. . . When they arrived at Gilgal private altars were permitted, offerings of the most sacred order were then eaten within the curtains, and offerings of lesser sanctity were eaten anywhere. When they arrived at Shiloh, private altars were prohibited. . .” (Zevachim 112b)

Later the Gemara explains that in Gilgal, Nov and Givon there was not only the Tent of Meeting with the large bama but individual bamot as well:

“Rabbi Yehuda says: Any offering that the public or an individual could sacrifice in the Tent of Meeting in the wilderness could also be sacrificed in the Tent of Meeting in Gilgal. What, then, is the difference between the Tent of Meeting in the wilderness and the Tent of Meeting in Gilgal? During the period of the Tent of Meeting in the wilderness private altars were not permitted while during the period of the Tent of Meeting in Gilgal private altars were permitted.” (Zevachim 117a)

These interim sites, between the full holy places of the desert, Shilo and Jerusalem, have an unusual status. One can offer both public sacrifices on the large bama, and individual offerings on private bamot. The Meiri on Masechet Megillah (9b) explains this strange status. He says that in Gilgal, Nov and Givon the desert altar was standing but the Ark of the Covenant was not by its side. In Gilgal, the Ark was going out to war with the Israelites, in their wars of conquest with Joshua. In Nov and Givon the Ark, returned from Philistine captivity, was waiting in Kiryat Yearim until the Temple was built. Without the Ark, the Tabernacle only had a semi-holy status and therefore the bamot were permitted.

The first of these transitional sites is Gilgal. The Gemara tells us (Zevachim 118b) that the Tabernacle was in Gilgal for fourteen years, the years that Joshua and the people conquered and divided up the land. Then it was moved to Shilo where it stayed for almost four centuries. Gilgal is very prominent in the book of Joshua, as well as in later Biblical books. What was its importance and can we identify where it was?

We first hear of Gilgal in Devarim, where we have very specific (but confusing) directions to Mount Gerizim and Mount Eival. From this verse, Gilgal seems to be located near the two mountains, and near Elon Moreh, next to Shechem:

“Both are on the other side of the Jordan, beyond the west road that is in the land of the Canaanites who dwell in the Arabah—near Gilgal, by the terebinths of Moreh.” (Devarim 11:31)

In the book of Joshua, Gilgal becomes more meaningful. It is the first camp of the Israelites after they cross the Jordan and the place where they erect a (second) monument of twelve stones, after they put one up in the Jordan itself:

“The people came up from the Jordan on the tenth day of the first month, and encamped at Gilgal on the eastern border of Jericho.” (Joshua 4:19)

Even more significantly, Gilgal is the place where the first Passover in the land of Israel is celebrated and where the people begin eating the produce of the land (Joshua 5:10). The Israelites stay camped in Gilgal, while venturing out to fight, and this is where the Givonim come and trick Joshua into making a covenant with them (Joshua 9:6). Joshua’s army leaves from Gilgal on a daring night raid to save the Givonim from the Canaanite kings who attack them:

“Joshua took them by surprise, marching all night from Gilgal.” (Joshua 10:9)

Gilgal appears again, numerous times, in the book of Samuel. It is part of Samuel’s judging circuit (Samuel I 7:16), the place where Saul is crowned for a second time (11:14) and the site of both times that Saul disobeys Samuel’s orders and loses the kingship (chapters 13 and 15). Clearly Gilgal had great religious and ritual importance if it was chosen to be the location of these events.

When Elijah goes on his final journey with Elisha, they travel from Bet El to Gilgal to Jericho to the Jordan. Elijah is doing a reverse entrance to the land, going to the sites of the book of Joshua but in the opposite order, taking leave of Israel and its people (Kings II 2). Finally, the prophets Amos and Hoshea condemn Gilgal as a place of false worship and tell the people to return to God:

“Do not seek Bethel,

Nor go to Gilgal,

Nor cross over to Beer-sheba;

For Gilgal shall go into exile,

And Bethel shall become a delusion.” (Amos 5:5)

These sources tell us that Gilgal was a place of religious importance for a long period, until the people started to abuse it and had to be directed back to the Temple and God. But where is it? And can we find any traces of it?

From the texts above there seem to be not one but a number of Gilgals. In Devarim, Gilgal is near Shechem, in the mountains of Samaria. In Joshua, it appears to be between the Jordan and Jericho. In the stories in the book of Samuel, it seems closer to Bet El and to Saul’s capital Givah, both in the area of Benjamin. How could they all be Gilgal?

One approach to this question is that Gilgal is just a name for a nomadic site, one that would leave few remains and could be located in a number of places. Searching for the “real” Gilgal would be useless since it was not a permanent site.

A daring and innovative approach was put forward by the maverick Israeli archaeologist Adam Zertal. In the 1980s, Zertal conducted an enormous archaeological survey of the area of Menashe. Alongside the discovery of the altar on Mount Eival, he also found a number of strange sites that seemed to be similar. They were large compounds, lower than the surrounding area, with a square or round bama inside them. The most unusual characteristic that these sites shared was that they were shaped like a footprint, and had a path around the perimeter that people could walk on. Five of the six sites could be dated by their pottery to the time of conquest of the land, approximately 1200 BCE. They also contained a form of a theater, a seating area where you could watch the events.

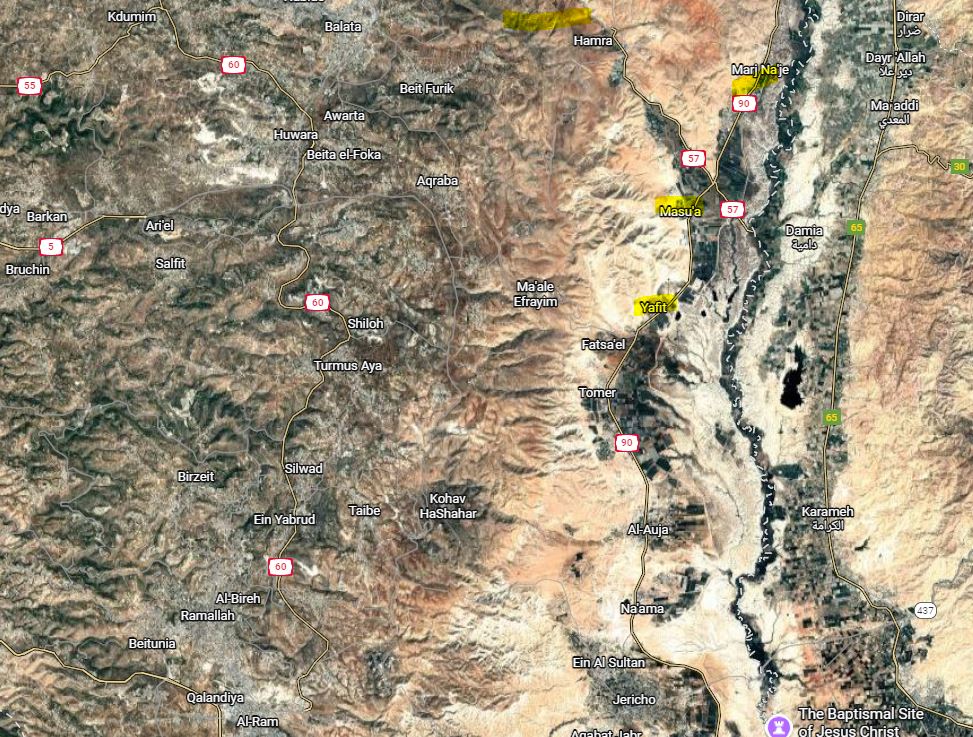

Highlighted places are some of the footprint sites

These sites are all located in the Jordan Valley, on Mount Eival or in the Tirtza Valley on the way to Shechem. The best preserved one is in Argaman, in the Jordan Valley. What were these “footprint” sites? Zertal believed that these are the earliest ritual sites of the Israelites in the land and that these were the “Gilgals.” They were used for sacrifices but also for a symbolic procession in the shape of a foot. Why a foot? The footprint symbolizes taking and keeping the land:

“Every spot on which your foot treads shall be yours;” (Devarim 11:24)

It can also be a symbol of subjugating our enemies and even of God’s power:

“Thus said GOD:

The heaven is My throne

And the earth is My footstool:” (Isaiah 66:1)

Holidays are known as regalim, feet, and ascending to Jerusalem is called aliya laregel. A holiday is called chag, from the word circle. Could these ancient sites hold the key not only to the identity of Gilgal but to the beginnings of our rituals?

The footprint site in Binyamin

Lipkin.Aaron, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons