Rava discusses more issues regarding a heiter iska. If a sharecropper who pays a fixed amount to the owner is not permitted to decide not to weed the field, for various reasons cited in the Mishna and Gemara. If one sharecrops for percentages and there is very little yield, the sharecropper does not assume responsibility. However, there is a minimum amount. What is that amount? The Gemara digresses to measurements in other areas of halakha including ritual impurity, particularly cases in which Rabbi Yannai takes a position. One who works in another’s land as a chokher and a plague or windblast ruins the crops – in which scenarios can the chokher pay less than the agreed upon amount?

Bava Metzia

Masechet Bava Metzia is sponsored by Rabbi Art Gould in memory of his beloved bride of 50 years, Carol Joy Robinson, Karina Gola bat Huddah v’Yehuda Tzvi.

רבות בנות עשו חיל ואת עלית על־כלנה

This week’s learning is sponsored for the merit and safety of Haymanut (Emuna) Kasau, who was 9 years old when she disappeared from her home in Tzfat two years ago, on the 16th of Adar, 5784 (February 25, 2024), and whose whereabouts remain unknown.

This week’s learning is dedicated of the safety of our nation, the soldiers and citizens of Israel, and for the liberation of the Iranian people. May we soon see the realization of “ליהודים היתה אורה ושמחה וששון ויקר”.

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Today’s daily daf tools:

Bava Metzia

Masechet Bava Metzia is sponsored by Rabbi Art Gould in memory of his beloved bride of 50 years, Carol Joy Robinson, Karina Gola bat Huddah v’Yehuda Tzvi.

רבות בנות עשו חיל ואת עלית על־כלנה

This week’s learning is sponsored for the merit and safety of Haymanut (Emuna) Kasau, who was 9 years old when she disappeared from her home in Tzfat two years ago, on the 16th of Adar, 5784 (February 25, 2024), and whose whereabouts remain unknown.

This week’s learning is dedicated of the safety of our nation, the soldiers and citizens of Israel, and for the liberation of the Iranian people. May we soon see the realization of “ליהודים היתה אורה ושמחה וששון ויקר”.

Today’s daily daf tools:

Delve Deeper

Broaden your understanding of the topics on this daf with classes and podcasts from top women Talmud scholars.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Bava Metzia 105

תְּרֵי עִיסְקֵי וְחַד שְׁטָרָא – פְּסֵידָא דְּלֹוֶה.

Conversely, if two people engaged in two joint ventures and recorded both in one document, this will be to the detriment of the borrower. They calculate the profits and losses of the two transactions together, and therefore as long as the profits of one joint venture are greater than the losses of the other, the investor will not have to suffer a loss.

וְאָמַר רָבָא: הַאי מַאן דְּקַבֵּיל עִיסְקָא מִן חַבְרֵיהּ וּפְסֵיד, טְרַח וּמַלְּיֵיהּ וְלָא אוֹדְעֵיהּ, לָא מָצֵי אֲמַר לֵיהּ: דְּרִי מֵהַיְאךְ פְּסֵידָא בַּהֲדַאי. מִשּׁוּם דַּאֲמַר לֵיהּ: לְהָכִי טְרַחְתְּ (לְמַלָּיוֹתֵיהּ) [וּמַלֵּיתֵיהּ] – כִּי הֵיכִי דְּלָא לִיקְרוֹ לָךְ ״מַפְסֵיד עִיסְקֵי״.

And Rava says: This one, who receives merchandise for a joint venture from another, and lost money in the process, and then made the effort to replace the loss but did not inform the investor that he had done so, he may not later say to the investor: Bear this original loss together with me. This is because the investor can say to him: It is for this reason that you made the effort to replace the loss, so that you should not be called a loser of ventures. You wanted to preserve your reputation in order to improve your future business prospects but did not intend to be reimbursed.

וְאָמַר רָבָא: הָנֵי בֵּי תְרֵי דְּעָבְדִי עִיסְקָא בַּהֲדֵי הֲדָדֵי וּרְוַוח, וַאֲמַר לֵיהּ חַד לְחַבְרֵיהּ: תָּא לִיפְלוֹג, אִי אֲמַר לֵיהּ אִידַּךְ: נַרְוַוח טְפֵי – דִּינָא הוּא דִּמְעַכֵּב. וְאִי אָמַר לֵיהּ: הַב לִי פַּלְגָא דְּרַוְוחָא – אָמַר לֵיהּ: רַוְוחָא – לְקַרְנָא מִשְׁתַּעְבֵּד.

And Rava said: With regard to these two managers who engaged in a joint venture together, i.e., they both received merchandise together from an investor, and profited from it, and one of them said to the other: Come, let us divide the profits and terminate the venture, the halakha is as follows: If the other said to him: Let us wait and profit more, the halakha is that the second manager indeed prevents the first from executing his request. And if, instead of requesting the final division of the profits and the termination of the venture, one said to the other: At least give me half the profits, the latter can say to him: The profit is liened to the principal, meaning that the profits and the principal are considered a single unit, and we can earn much more if we do not set aside the profits.

וְאִי אָמַר לֵיהּ: הַב לִי פַּלְגָא רַוְוחָא וּפַלְגָא קַרְנָא – אָמַר לֵיהּ: עִיסְקָא לַהֲדָדֵי מְשׁוּעְבַּד. וְאִי אָמַר לֵיהּ: נִפְלוֹג רַוְוחָא וְנִפְלוֹג קַרְנָא, וְאִי מָטֵי לָךְ פְּסֵידָא דָּרֵינָא בַּהֲדָךְ – אָמַר לֵיהּ: לָא מַזָּלָא דְּבֵי תְרֵי עָדִיף.

Rava continues: And if one says to the other: Give me half the profits and half the principal, the latter can say to him: The merchandise for the joint venture is liened to both of us. As we are equal partners in this venture, you cannot force me to divide it. And if one says to the other: Let us divide the profits and divide the principal, and if you suffer a loss as a result, I will bear the loss with you, his partner can say to him: No, I do not desire to do that, since the luck of two people is better. Consequently, I want to continue working together. In all these cases, the claims of the second manager are accepted.

מַתְנִי׳ הַמְקַבֵּל שָׂדֶה מֵחֲבֵירוֹ וְלֹא רָצָה לְנַכֵּשׁ, וְאָמַר לוֹ: מָה אִיכְפַּת לְךָ? הוֹאִיל וַאֲנִי נוֹתֵן לְךָ אֶת חֲכִירָךְ – אֵין שׁוֹמְעִין לוֹ. מִפְּנֵי שֶׁיָּכוֹל לוֹמַר לוֹ: לְמָחָר אַתָּה יוֹצֵא מִמֶּנָּה וּמַעֲלֵת לְפָנַי עֲשָׂבִים.

MISHNA: With regard to one who received a field from another to cultivate and did not want to weed it, and he then said to the owner: What do you care if I neglect the land? You will not suffer a loss since I will give you the amount of produce I owe you for your granting me tenancy, regardless of the state of the field. Nevertheless, they do not listen to him. The reason is because the owner of the land can say to him: Tomorrow you will depart from the field, and it will grow weeds for me, which will remain there and disrupt the yield of the field for years to come.

גְּמָ׳ אִי אָמַר לֵיהּ: לְבָתַר הָכִי כָּרֵיבְנָא לַהּ – אָמַר לֵיהּ: חִטֵּי מְעַלְּיָיתָא בָּעֵינָא. וְאִי אָמַר לֵיהּ: זָבֵינְנָא לָךְ חִטֵּי מִשּׁוּקָא – אָמַר לֵיהּ: חִטֵּי דְּאַרְעַאי בָּעֵינָא. וְאִי אָמַר לֵיהּ מְנַכֵּישְׁנָא לָךְ שִׁיעוּר מְנָתָיךְ – אָמַר לֵיהּ: קָא מַנְסְבַתְּ שֵׁם רַע לְאַרְעַאי.

GEMARA: If the cultivator said to the owner: Afterward, when I have reaped the field, I will plow it and remove the weeds, the owner can say to him: I want superior wheat, not wheat that sprouted among weeds. And if he says to the owner: I will buy good wheat for you from the market, the owner can say to him: I want wheat from my land. And if he says to the owner: I will weed for you according to the measure of your portion, but no more, the owner can say to him: You are giving a bad name to my land, as everyone will see that it is full of weeds.

וְהָתְנַן: מִפְּנֵי שֶׁמַּעֲלֵת לְפָנַי עֲשָׂבִים! אֶלָּא מִשּׁוּם דְּאָמַר לֵיהּ: בִּזְרָא דִּנְפַל – נְפַל.

The Gemara asks: But didn’t we learn in the mishna that the reason they do not listen to him is: Because it will grow weeds for me, indicating that these other claims are not accepted? Rather, the explanation must be because the owner can say to him: The seed that fell has fallen. In other words, even if the cultivator later plows the land and uproots all of the weeds, their seeds remain in the ground and will sprout in the following years.

מַתְנִי׳ הַמְקַבֵּל שָׂדֶה מֵחֲבֵירוֹ וְלֹא עָשְׂתָה, אִם יֵשׁ בָּהּ כְּדֵי לְהַעֲמִיד כְּרִי – חַיָּיב לִטַּפֵּל בָּהּ. אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: מַאי קִצְבָה בִּכְרִי? אֶלָּא אִם יֵשׁ בָּהּ כְּדֵי נְפִילָה.

MISHNA: With regard to one who receives a field from another to cultivate and it did not produce a sufficient crop to cover the expenses of its upkeep, if it has enough produce to form a pile he is obligated to take care of it and give the owner his share. Rabbi Yehuda says: What fixed measure is a pile? There is no inherent measure of produce that is considered significant, as it all depends on the size of the plot of land in question. Rather, the relevant issue is whether it has a crop equivalent to the measure of seeds for dropping in a field in order to sow it.

גְּמָ׳ תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: הַמְקַבֵּל שָׂדֶה מֵחֲבֵירוֹ וְלֹא עָשְׂתָה, אִם יֵשׁ בָּהּ כְּדֵי לְהַעֲמִיד כְּרִי – חַיָּיב לִטַּפֵּל בָּהּ. שֶׁכָּךְ כּוֹתֵב לוֹ: אֲנָא אֵוקֹים וְאֵנוּר וְאֶזְרַע וְאֶחְצוֹד וַאֲעַמַּר וְאֵדוּשׁ וְאֶידְרֵי וְאוֹקֵים כַּרְיָא קׇדָמָךְ, וְתֵיתֵי אַנְתְּ וְתִיטּוֹל פַּלְגָא, וַאֲנָא בְּעַמְלִי וּבְנַפְקוּת יְדַי פַּלְגָא.

GEMARA: The Sages taught: With regard to one who receives a field from another to cultivate and it did not produce a sufficient crop, if it has enough produce to form a pile he is obligated to take care of it and provide the owner with his share. This is because this is what he writes to him in the cultivator’s contract: I will stand and plow and plant and reap and bind and thresh and winnow and establish a pile before you, and you will come and take half, and I, for my work and expenses, will take the other half. Based on this contract, if there is sufficient produce to form a pile, the cultivator must fulfill the terms of the agreement.

וְכַמָּה כְּדֵי לְהַעֲמִיד בָּהּ כְּרִי? אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בְּרַבִּי חֲנִינָא: כְּדֵי שֶׁתַּעֲמוֹד בּוֹ הָרַחַת. אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: רַחַת הַיּוֹצֵא מֵהַאי גִּיסָא לְהַאי גִּיסָא, מַאי?

The Gemara asks: And how much is the amount of: Enough to form a pile? How large must the pile be? Rabbi Yosei, son of Rabbi Ḥanina, said: Enough for the winnowing shovel to stand in it. If the pile is big enough that the shovel can be placed there and stand independently without falling, it is considered a sufficiently large pile. A dilemma was raised before the Sages: With regard to a winnowing shovel that protrudes from this side to that side, i.e., whose edges extend beyond the pile, what is the halakha? Is this considered a pile in which a winnowing shovel can stand or not?

תָּא שְׁמַע: אָמַר רַבִּי אֲבָהוּ, לְדִידִי מִפָּרְשָׁא לִי מִינֵּיהּ דְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בְּרַבִּי חֲנִינָא: כֹּל שֶׁאֵין כּוֹנֵס שֶׁלּוֹ רוֹאֶה פְּנֵי הַחַמָּה. אִיתְּמַר: לֵוִי אָמַר שָׁלֹשׁ סְאִין, דְּבֵי רַבִּי יַנַּאי אָמְרִי סָאתַיִם. אָמַר רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ: סָאתַיִם שֶׁאָמְרוּ חוּץ מִן הַהוֹצָאָה.

The Gemara suggests: Come and hear a proof from that which Rabbi Abbahu said: This was explained to me by Rabbi Yosei, son of Rabbi Ḥanina: Any pile in which the blade of the winnowing shovel cannot see the face of the sun because it is covered by the pile is considered a significant one. It was stated that the amora’im engaged in a dispute concerning this issue: Levi says: This pile must be three se’a in size, while the Sages of the school of Rabbi Yannai say: Two se’a. Reish Lakish says: The two se’a of which they spoke is without deducting the expenses. Consequently, if he has paid the expenses and a profit of two se’a remains, in that case alone it is considered worthwhile to work the field. But if it cannot produce this amount, the cultivator may neglect the land if he so chooses.

תְּנַן הָתָם: פָּרִיצֵי זֵיתִים וַעֲנָבִים, בֵּית שַׁמַּאי מְטַמְּאִין, וּבֵית הִלֵּל מְטַהֲרִין.

The Gemara cites a dispute from a different area of halakha that discusses a similar measurement: We learned in a mishna there (Okatzin 3:6) concerning the halakhot of food impurities: With regard to unruly olives and grapes, Beit Shammai hold that they become susceptible to ritual impurity, as they are considered food, and Beit Hillel hold that they do not become susceptible to ritual impurity because they are of inferior quality and are unfit for consumption.

מַאי פָּרִיצֵי זֵיתִים? אָמַר רַב הוּנָא: רִשְׁעֵי זֵיתִים. אָמַר רַב יוֹסֵף: וּמַאי קְרָאָה – ״[וּבְנֵי] פָּרִיצֵי עַמְּךָ יִנַּשְּׂאוּ לְהַעֲמִיד חֲזוֹן וְנִכְשָׁלוּ״. רַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק אָמַר: מֵהָכָא – ״וְהוֹלִיד בֵּן פָּרִיץ שֹׁפֵךְ דָּם״.

The Gemara asks: What is the meaning of unruly [peritzei] olives? Rav Huna said: Wicked olives, i.e., olives that barely produce any oil. Rav Yosef said: And what is the verse from which it is derived? “Also the children of the wicked [peritzei] among your people shall raise themselves up to establish the vision but they shall stumble” (Daniel 11:14). This verse indicates that the word peritzei means wicked. Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak said that the meaning of this word can be derived from here: “If he beget a son that is a robber [paritz], a shedder of blood” (Ezekiel 18:10).

וְכַמָּה פָּרִיצֵי זֵיתִים? רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר אָמַר: אַרְבַּעַת קַבִּין לַקּוֹרָה. דְּבֵי רַבִּי יַנַּאי אָמְרִי: סָאתַיִם לַקּוֹרָה.

The Gemara asks: And how much is the amount of unruly olives? When are olives classified as unruly? Rabbi Elazar says: They are classified as such if it is possible to extract only four kav of oil from one press of the beam when the fruits are brought in together to the olive press. The Sages of the school of Rabbi Yannai say: They are classified as such if it is possible to extract only two se’a of oil from one press of the beam.

וְלָא פְּלִיגִי: הָא בְּאַתְרָא דִּמְעַיְּילִי כּוֹרָא בְּאוֹלָלָא, הָא בְּאַתְרָא דִּמְעַיְּילִי תְּלָתָא כּוֹרִין בְּאוֹלָלָא.

The Gemara comments: And these Sages do not disagree with regard to the halakha itself, as the difference between their rulings stems from divergent local practices. This statement of Rabbi Elazar is referring to a place where one kor is brought into the press, from which he must be able to extract four kav, whereas that halakha of the school of Rabbi Yannai is referring to a place where three kor are brought into the baskets of the oil press. Since they bring in three times the amount of fruit, it must produce exactly three times as much oil.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן:

The Sages taught:

עָלוּ בְּאִילָן שֶׁכּוֹחוֹ רַע, וּבְסוֹכָה שֶׁכּוֹחָהּ רַע – טָמֵא.

If a zav and a ritually pure person climbed a tree that has little strength, which shook as they climbed it, or if they climbed onto a branch that has little strength, the ritually pure person is rendered ritually impure. One of the ways a zav imparts impurity is by movement, and here the zav is viewed as having moved the pure person.

הֵיכִי דָּמֵי אִילָן שֶׁכּוֹחוֹ רַע? אָמְרִי דְּבֵי רַבִּי יַנַּאי: כֹּל שֶׁאֵין בְּעִיקָּרוֹ לָחוֹק רוֹבַע. הֵיכִי דָּמֵי סוֹכָה שֶׁכּוֹחָהּ רַע? אָמַר רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ: כֹּל שֶׁנֶּחְבֵּאת בְּחֶזְיוֹנָהּ.

The Gemara asks: What are the circumstances of this tree that has little strength, i.e., how is a tree with little strength defined? The Sages of the school of Rabbi Yannai say: It is any tree whose trunk is not broad enough that one can hollow out a vessel of a quarter–kav from it. What are the circumstances of a branch that has little strength? Reish Lakish said: It is any branch concerning which its circumference can be hidden, i.e., inserted, in a person’s fist. A branch of this size is generally not strong enough to hold two people without shaking.

תְּנַן הָתָם: הַמְהַלֵּךְ בְּבֵית הַפְּרָס, עַל גַּבֵּי אֲבָנִים שֶׁיָּכוֹל לְהָסִיט, עַל הָאָדָם וְעַל הַבְּהֵמָה שֶׁכּוֹחָן רַע – טָמֵא.

We learned in a mishna elsewhere (Oholot 18:6): With regard to one who walks in an area in which uncertainty exists concerning the location of a grave or corpse [beit haperas], if he treads over stones that he can move as he walks, raising concerns that he might have moved a bone of a corpse and thereby rendered himself impure, or if he was in that location, on the back of a person or riding on an animal that had little strength, he is impure, as he is considered to have moved the impurity himself.

הֵיכִי דָּמֵי אָדָם שֶׁכּוֹחוֹ רַע? אָמַר רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ: כֹּל שֶׁרוֹכְבוֹ וְאַרְכֻבּוֹתָיו נוֹקְשׁוֹת. הֵיכִי דָּמֵי בְּהֵמָה שֶׁכּוֹחָהּ רַע? אָמְרִי דְּבֵי רַבִּי יַנַּאי: כֹּל שֶׁרוֹכְבָהּ [וּ]מְטִילָה גְּלָלִים.

The Gemara asks: What are the circumstances of a person that has little strength? Reish Lakish said: Any person whose knees knock against each other when someone rides upon him. What are the circumstances of an animal that has little strength? The Sages of the school of Rabbi Yannai say: Any animal that releases excrement due to strain when a person rides upon it.

אָמְרִי דְּבֵי רַבִּי יַנַּאי: לִתְפִלָּה וְלִתְפִילִּין אַרְבָּעָה קַבִּין.

§ As the Gemara has cited the rulings of the school of Rabbi Yannai with regard to measurements, it now cites similar halakhot that the Sages of the school of Rabbi Yannai state: With regard to prayer and with regard to phylacteries, the measure is four kav.

לִתְפִלָּה מַאי הִיא? דְּתַנְיָא: הַנּוֹשֵׂא מַשּׂאוֹי עַל כְּתֵיפוֹ וְהִגִּיעַ זְמַן תְּפִלָּה, פָּחוֹת מֵאַרְבָּעָה קַבִּין – מַפְשִׁילָין לַאֲחוֹרָיו וּמִתְפַּלֵּל. אַרְבָּעָה קַבִּין – מַנִּיחַ עַל גַּבֵּי קַרְקַע וּמִתְפַּלֵּל.

The Gemara inquires: What is the relevance of this measure with regard to prayer? This is as it is taught in a baraita: With regard to one who carries a load on his shoulder and the time for prayer arrives, if the load is less than four kav, he lowers it behind him while still holding it and prays, as a light load of this size does not interfere with prayer. If the load is four kav, he places it on the ground and prays.

לִתְפִילִּין מַאי – הִיא דְּתַנְיָא: הָיָה נוֹשֵׂא מַשּׂאוֹי עַל רֹאשׁוֹ וּתְפִילִּין בְּרֹאשׁוֹ, אִם הָיוּ תְּפִילִּין רוֹצְצוֹת – אָסוּר, וְאִם לָאו – מוּתָּר. בְּאֵיזוֹ מַשּׂאוֹי אָמְרוּ – בְּמַשּׂאוֹי שֶׁל אַרְבַּעַת קַבִּין.

What is the relevance of this amount with regard to phylacteries? This is as it is taught in a baraita: If a man was carrying a load on his head and he had phylacteries on his head, if the phylacteries were being crushed under the load it is forbidden to leave them on his head, but if they were not being crushed, it is permitted. With regard to which load did the Sages state this halakha? They stated it with regard to a load of four kav.

תָּנֵי רַבִּי חִיָּיא: הַמּוֹצִיא זֶבֶל עַל רֹאשׁוֹ וּתְפִילִּין בְּרֹאשׁוֹ – הֲרֵי זֶה לֹא יְסַלְּקֵם לִצְדָדִין, וְלֹא יִקְשְׁרֵם בְּמׇתְנָיו, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁהוּא נוֹהֵג בָּהֶן מִנְהַג בִּזָּיוֹן. אֲבָל קוֹשְׁרָם עַל זְרוֹעוֹ בִּמְקוֹם תְּפִילִּין.

Rabbi Ḥiyya teaches: With regard to one who removes garbage by carrying it on his head and has phylacteries on his head, he may not move the phylacteries to the side to prevent them from being crushed, and likewise he may not tie the phylacteries of the head to his loins because he thereby treats them in a manner of degradation. But he may tie them on his arm in the location where the phylacteries of the hand are placed.

מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי שֵׁילָא אָמְרוּ: אֲפִילּוּ מִטְפַּחַת שֶׁלָּהֶן אָסוּר לְהַנִּיחַ עַל הָרֹאשׁ שֶׁיֵּשׁ בּוֹ תְּפִילִּין. וְכַמָּה? אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: אֲפִילּוּ רִבְעָא דְּרִבְעָא דְּפוּמְבְּדִיתָא.

The Sages said in the name of the school of Sheila: It is forbidden to place on the head of one that has phylacteries on it even the scarf in which they are wrapped. The Gemara asks: And how much does Rabbi Sheila permit one to place on his head while wearing phylacteries? Abaye said: Even as little as one-quarter of one-quarter of the smallest measurement of Pumbedita is still forbidden from being placed on one’s head.

אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: מַאי קִצְבָה בִּכְרִי? אֶלָּא: אִם יֵשׁ בּוֹ כְּדֵי נְפִילָה. וְכַמָּה כְּדֵי נְפִילָה? רַבִּי אַמֵּי אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: אַרְבַּעה סְאִין לְכוֹר. רַבִּי אַמֵּי דִּילֵיהּ אָמַר: שְׁמוֹנַת סְאִין לְכוֹר. אֲמַר לֵיהּ הָהוּא סָבָא לְרַב חָמָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַבָּה בַּר אֲבוּהּ: אַסְבְּרַהּ לָךְ, בִּשְׁנֵי דְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן הֲוָה שַׁמִּינָא אַרְעָא, בִּשְׁנֵי דְּרַבִּי אַמֵּי הֲוָה כְּחִישָׁא אַרְעָא.

§ The mishna teaches: Rabbi Yehuda says: What fixed measure is a pile? Rather, the relevant issue is whether it has a crop equivalent to the measure of seeds for dropping in a field in order to sow it. The Gemara asks: And how much is equivalent to the measure of seeds for dropping in a field in order to sow it? Rabbi Ami says that Rabbi Yoḥanan says: Four se’a for the amount of land sufficient to grow a kor. Rabbi Ami himself, though, says eight se’a for the amount of land sufficient to grow a kor. A certain elder said to Rav Ḥama, son of Rabba bar Avuh: I will explain it to you: In the years of Rabbi Yoḥanan the land was fat, while in the years of Rabbi Ami the land was lean, and it was therefore necessary to double the amount of seed for each unit of land.

תְּנַן הָתָם: הָרוּחַ שֶׁפִּיזְּרָה אֶת הָעוֹמָרִין, אוֹמְדִים אוֹתָהּ כַּמָּה לֶקֶט רְאוּיָה לַעֲשׂוֹת וְנוֹתֵן לַעֲנִיִּים. רַבָּן שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל אוֹמֵר: נוֹתֵן לַעֲנִיִּים כְּדֵי נְפִילָה.

We learned in a mishna elsewhere (Pe’a 5:1): If the wind scattered the standing sheaves so that it is no longer known which gleanings fell from the sheaves during the harvest and belong to the poor, one evaluates how many gleanings it was fit to produce, and he gives these to the poor. Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel says: He gives to the poor the amount equivalent to the measure of seeds dropping in the course of harvesting.

וְכַמָּה כְּדֵי נְפִילָה? כִּי אֲתָא רַב דִּימִי, אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר וְאִיתֵּימָא רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: אַרְבַּעַת קַבִּין לְכוֹר. בָּעֵי רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה: לְכוֹר זֶרַע, אוֹ לְכוֹר תְּבוּאָה? לְמַפּוֹלֶת יָד, אוֹ לְמַפּוֹלֶת שְׁווֹרִים?

The Gemara asks: And how much is the amount equivalent to the measure of seeds dropping in the course of harvesting? When Rav Dimi came from Eretz Yisrael he said that Rabbi Elazar said, and some say it was Rabbi Yoḥanan: Four kav for a kor. Rabbi Yirmeya raised a dilemma: Does this mean for a field that requires a kor of seed to plant it, or for a kor of produce? And if it is the former, does it refer to sowing by hand or to sowing by oxen?

תָּא שְׁמַע, דְּכִי אֲתָא רָבִין, אָמַר רַבִּי אֲבוּהּ אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר, וְאָמְרִי לָהּ אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: אַרְבַּעַת קַבִּין לְכוֹר זֶרַע. וַעֲדַיִין תִּבְּעֵי לָךְ: לְמַפּוֹלֶת יָד אוֹ לְמַפּוֹלֶת שְׁווֹרִים? תֵּיקוּ.

The Gemara answers: Come and hear, as when Ravin came from Eretz Yisrael he said that Rabbi Avuh said that Rabbi Elazar said, and some say that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: Four kav for a field sown with a kor of seed. The Gemara comments: And the other question should still raise a dilemma for you: Does this refer to sowing by hand or to sowing by oxen? No answer was found for this question, and the dilemma shall stand unresolved.

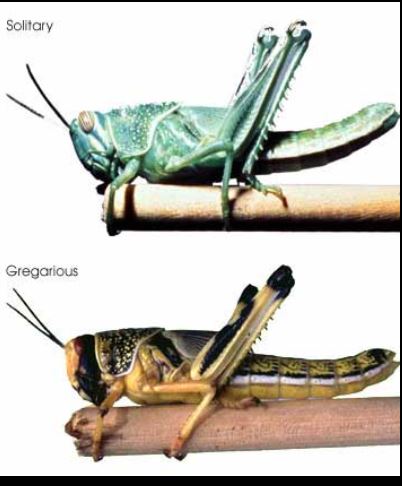

מַתְנִי׳ הַמְקַבֵּל שָׂדֶה מֵחֲבֵירוֹ וַאֲכָלָהּ חָגָב, אוֹ נִשְׁדְּפָה. אִם מַכַּת מְדִינָה הִיא – מְנַכֶּה לוֹ מִן חֲכוֹרוֹ. אִם אֵינָהּ מַכַּת מְדִינָה – אֵין מְנַכֶּה לוֹ מִן חֲכוֹרוֹ. רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: אִם קִיבְּלָהּ הֵימֶנּוּ בְּמָעוֹת, בֵּין כָּךְ וּבֵין כָּךְ אֵינוֹ מְנַכֶּה לוֹ מֵחֲכוֹרוֹ.

MISHNA: In the case of one who receives a field from another to cultivate and grasshoppers consumed it or it was wind blasted, if it is a regional disaster which affected all the fields in the area, the cultivator subtracts from the produce he owes as part of his tenancy. If it is not a regional disaster, the cultivator does not subtract from the produce he owes as part of his tenancy. Rabbi Yehuda says: If the cultivator received it from the owner for a fixed sum of money, whether this way, i.e., there is a regional disaster, or whether that way, i.e., there was no regional disaster, he does not subtract the produce he owes as part of his tenancy.

גְּמָ׳ הֵיכִי דָמֵי מַכַּת מְדִינָה? אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה: כְּגוֹן דְּאִישְׁתְּדוּף רוּבָּא דְבָאגָא. עוּלָּא אָמַר: כְּגוֹן שֶׁנִּשְׁתַּדְּפוּ אַרְבַּע שָׂדוֹת מֵאַרְבַּע רוּחוֹתֶיהָ.

GEMARA: The Gemara asks: What are the circumstances of a regional disaster? Rav Yehuda said: If, for example, most of that valley in which the field was located was wind blasted, it is considered a regional disaster. Ulla said: If, for example, four fields were wind blasted on its four sides, it is considered a regional disaster.

אָמַר עוּלָּא, בָּעוּ בְּמַעְרְבָא: נִשְׁדַּף תֶּלֶם אֶחָד עַל פְּנֵי כּוּלָּהּ, מַאי? נִשְׁתַּיֵּיר תֶּלֶם אֶחָד עַל פְּנֵי כּוּלָּהּ, מַהוּ? אִפְּסִיקא בְּיָרָא, מַאי? אַסְפַּסְתָּא,

Ulla also said: They raise the following dilemma in the West, Eretz Yisrael: If one furrow was wind blasted along its entire length, adjacent to other fields that were wind blasted, what is the halakha? Is this considered to be part of the regional disaster? Conversely, if one furrow remained undamaged along its entire length, what is the halakha? Does the remaining furrow mean that the entire field is not considered to be part of the regional disaster? If a fallow field divided between the cultivated fields and the fields that were wind blasted, what is the halakha? Alternatively, if there was a field of fodder between this field and the others that were wind blasted,