There are laws regarding clearing out an entire storage area, moving items from one roof to the next, or bringing items down from the roof using a rope that were forbidden either on Yom Tov or Shabbat and the Gemara ponders whether it would also be forbidden as well on Shabbat/Yom Tov, relying on the differences discussed at the end of Beitzah 35. The Mishna stated that one could cover fruits if there is water dripping on them. Ulla and Rabbi Yitzchak disagree about whether this is only true for fruits that are ready to be eaten or whether this would apply even to a pile of bricks. The Gemara tries to bring proofs for each of the opinions from our Mishna and other tannaitic sources. However, each proof is rejected as it can be explained according to the other opinion as well. One can put out a utensil to catch water dripping from the roof and can keep emptying it and letting it refill. A story is told of Abaye who didn’t take the advice of Raba when water was dripping on his millstone and Raba suggested he bring out his bed and that will them create a situation where he can move the water as it is disgusting to sleep next to it (just as one can move a bowl full of bodily waste). Items that are disgusting are permitted to be moved on Shabbat, even if they are muktze. In the end, his millstone fell (as the water moistened the dirt that it was standing on), and was destroyed. He blamed himself for not heeding Raba’s advice. A utensil used for bodily waste can be carried out and emptied into the garbage, but can it be brought back inside? If so, how? The Mishna lists different categories of things that are forbidden on both Shabbat and Yom Tov and provides examples of each. The categories divide into actions that are forbidden that have no mitzva associated with them, actions that are forbidden even though they are somewhat of a mitzva, and actions that are forbidden, even though they are a mitzvah. The Gemara starts going through the actions listed in the first category and explains why each action is forbidden. In the second category, the Gemara questions some of the cases as they actually seem to be a proper mitzva and answers each question.

Beitzah 36

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Today’s daily daf tools:

Today’s daily daf tools:

Delve Deeper

Broaden your understanding of the topics on this daf with classes and podcasts from top women Talmud scholars.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Beitzah 36

הָתָם תְּנַן ״אֲבָל לֹא אֶת הָאוֹצָר״, וְאָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: מַאי ״אֲבָל לֹא אֶת הָאוֹצָר״ — אֲבָל לֹא יִגְמוֹר אֶת הָאוֹצָר כּוּלּוֹ, דִּלְמָא אָתֵי לְאַשְׁוֹיֵי גּוּמּוֹת. הָכָא מַאי?

The Gemara poses another question with regard to the same issue. We learned elsewhere, at the end of the mishna cited above concerning clearing out sacks for guests and study: But one may not clear out a storeroom. And Shmuel said: What is the meaning of: But not a storeroom? It means: But one may not finish clearing out the entire storeroom while clearing out the sacks, exposing the floor of the storeroom. The reason this is prohibited is lest he come to level out depressions in the dirt floor of the storeroom, which would constitute a biblically prohibited labor. What would be the halakha here, with regard to lowering the produce from the roof on a Festival to prevent its ruin in the rain? Is it prohibited also in this case to remove all of it and thereby expose the floor of the roof?

הָתָם הוּא בְּשַׁבָּת דְּאָסוּר — מִשּׁוּם דַּחֲמִיר, אֲבָל יוֹם טוֹב דְּקִיל — שַׁפִּיר דָּמֵי. אוֹ דִלְמָא: הָתָם דְּאִיכָּא בִּטּוּל בֵּית הַמִּדְרָשׁ — אָמְרַתְּ לָא, הָכָא דְּלֵיכָּא בִּטּוּל בֵּית הַמִּדְרָשׁ — לֹא כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן.

The Gemara specifies the possible arguments: Perhaps it is there, on Shabbat, that it is prohibited, because punishment for Shabbat desecration is severe, but on a Festival, which has a lighter punishment for desecration, it is acceptable. Or perhaps it can be argued to the contrary: There, in the case of the sacks on Shabbat, even though there is suspension of study in the study hall, i.e., the clearing out facilitates a mitzva, you say that they did not permit exposing the floor. Here, in the case of lowering produce on a Festival to prevent its ruin, where there is no suspension of study in the study hall, i.e., clearing out the produce does not facilitate any mitzva, is it not all the more so prohibited?

וְהָכָא תְּנַן: מַשִּׁילִין פֵּירוֹת דֶּרֶךְ אֲרוּבָּה בְּיוֹם טוֹב, וְאָמַר רַב נַחְמָן: לֹא שָׁנוּ אֶלָּא בְּאוֹתוֹ הַגָּג, אֲבָל מִגַּג לְגַג — לָא. וְתַנְיָא נָמֵי הָכִי: אֵין מְטַלְטְלִין מִגַּג לְגַג אֲפִילּוּ כְּשֶׁגַּגּוֹתֵיהֶן שָׁוִין.

The Gemara poses a further question. And here we learned in the mishna: One may lower produce through a skylight on a Festival, and Rav Naḥman said: They taught this halakha only with regard to the same roof, i.e., only if the skylight is in the same roof where the produce is located, but to carry the produce from one roof to another roof in order to lower it through a skylight in the second roof is not permitted. This would involve too much exertion to be permitted on the Festival. And this ruling is also taught in a baraita: One may not carry from one roof to another roof, even when the two roofs are on the same level and there is no extra effort of lifting or lowering the produce while transporting it between the roofs.

הָתָם מַאי? (כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן שַׁבָּת דַּחֲמִירָא, אוֹ דִלְמָא:) הָכָא הוּא דְּאָסוּר — מִשּׁוּם יוֹם טוֹב דְּקִיל, וְאָתֵי לְזַלְזוֹלֵי בֵּיהּ, אֲבָל שַׁבָּת דַּחֲמִירָא, וְלָא אָתֵי לְזַלְזוֹלֵי בַּהּ — שַׁפִּיר דָּמֵי.

The question arises: There, in the case of moving sacks on Shabbat for guests or for study, what is the halakha? May the sacks be moved from one roof or house to another for this purpose? Perhaps all the more so they may not be moved on Shabbat, because Shabbat is more severe than a Festival? Or perhaps it can be argued to the contrary: It is here, with regard to a Festival, that it is prohibited to transfer from one roof to another, because a Festival is regarded lightly by people and they might consequently come to belittle it; but on Shabbat, which is severe in people’s eyes and so they will not come to belittle it, it is acceptable to transfer even from one house to another.

אוֹ דִלְמָא: מָה הָכָא דְּאִיכָּא הֶפְסֵד פֵּירוֹת — אָמְרַתְּ לָא, הָתָם דְּלֵיכָּא הֶפְסֵד פֵּירוֹת — לֹא כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן.

Or perhaps it may be argued: If here, in the case of clearing produce from the roof, when there is the issue of the loss of the produce, you say he may not transfer from one roof to another, then there, in the case of moving sacks on Shabbat for guests or study, when there is no issue of loss of produce, is it not all the more so prohibited?

הָכָא (תְּנַן): לֹא יְשַׁלְשְׁלֵם בְּחֶבֶל בְּחַלּוֹנוֹת, וְלֹא יוֹרִידֵם דֶּרֶךְ סוּלָּמוֹת, הָתָם מַאי? הָכָא בְּיוֹם טוֹב הוּא דְּאָסוּר — דְּלֵיכָּא בִּטּוּל בֵּית הַמִּדְרָשׁ, אֲבָל שַׁבָּת, דְּאִיכָּא בִּטּוּל בֵּית הַמִּדְרָשׁ — שַׁפִּיר דָּמֵי.

The Gemara presents yet another dilemma: Here, with regard to bringing produce into one’s house from the roof, we learned in a baraita: If there is no skylight from the roof to the house, necessitating another method of moving the produce out of the rain, he may not lower them by means of a rope through the windows, nor may he take them down by way of ladders. There, with regard to moving sacks on Shabbat, what is the halakha? May they be moved by ropes or using a ladder? Perhaps it is only here, in the case of moving produce out of the rain on a Festival, that it is prohibited, because produce left on a roof does not entail suspension of a mitzva such as study in the study hall; but on Shabbat, when there is the possibility that leaving the sacks in their current location will lead to suspension of study in the study hall, it is acceptable to remove them even via windows and ladders.

אוֹ דִלְמָא: הָכָא דְּאִיכָּא הֶפְסֵד פֵּירוֹת — אָמְרַתְּ לָא, הָתָם דְּלֵיכָּא הֶפְסֵד פֵּירוֹת — לֹא כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן. תֵּיקוּ.

Or perhaps it can be argued to the contrary: Here, in the case of the produce on the roof, when there is the issue of the loss of the produce, you say it is not permitted. There, in the case of clearing out sacks on Shabbat, where there is no issue of the loss of produce, should it not all the more so be prohibited to lower them via windows and ladders? No resolution was found, so the dilemma shall stand unresolved.

וּמְכַסִּין אֶת הַפֵּירוֹת. אָמַר עוּלָּא: וַאֲפִילּוּ אַוֵּירָא דְלִבְנֵי. רַבִּי יִצְחָק אָמַר: פֵּירוֹת הָרְאוּיִן. וְאַזְדָּא רַבִּי יִצְחָק לְטַעְמֵיהּ. דְּאָמַר רַבִּי יִצְחָק: אֵין כְּלִי נִיטָּל אֶלָּא לְדָבָר הַנִּיטָּל בְּשַׁבָּת.

§ It was taught in the mishna: And one may cover produce with cloths to prevent damage due to a leak. Ulla said: And even a row of bricks that might be ruined by the rain may be covered to prevent damage. Although the halakha in the mishna mentions produce, it is not limited to that case, but extends to any item liable to be spoiled. Rabbi Yitzḥak said: It applies only to an item like produce, which is fit for use on the Festival, but not to items such as bricks, which are designated for building and are not fit for use on the Festival. The Gemara comments: And Rabbi Yitzḥak follows his line of reasoning in this regard, as Rabbi Yitzḥak said: A vessel, even if it is of the type that may be handled on Shabbat, may be handled on Shabbat only if it is going to be used for something that may itself be handled on Shabbat, but not for the sake of set-aside [muktze] objects. Since the bricks are muktze, one may not handle cloths to cover the bricks.

תְּנַן: מְכַסִּין אֶת הַפֵּירוֹת בְּכֵלִים. פֵּירוֹת — אִין, אַוֵּירָא דְלִבְנֵי — לָא! הוּא הַדִּין דַּאֲפִילּוּ אַוֵּירָא דְלִבְנֵי, וְאַיְּידֵי דִּתְנָא רֵישָׁא מַשִּׁילִין פֵּירוֹת — תְּנָא סֵיפָא נָמֵי מְכַסִּין אֶת הַפֵּירוֹת.

The Gemara attempts to find a proof for this view: We learned in the mishna: One may cover produce with cloths, which seems to imply: Produce, yes, because it may be handled on the Festival, but muktze items such as a row of bricks, no. The Gemara rejects this argument: This is no proof, as it is possible that the same is true even for a row of bricks, i.e., that they may be covered. But since the tanna taught in the first clause of the mishna: One may lower produce, and there it is referring specifically to produce, as bricks may not be handled at all and surely not lowered from the roof, he taught also in the latter clause: One may cover produce. The example of produce was chosen to parallel the first clause in the mishna, not in order to imply exclusion of bricks.

תְּנַן: וְכֵן כַּדֵּי יַיִן וְכֵן כַּדֵּי שֶׁמֶן! הָכָא בְּמַאי עָסְקִינַן, בְּטִיבְלָא.

The Gemara offers a different proof. We learned in the mishna: And similarly one may cover jugs of wine and jugs of oil due to a leak in the ceiling. This choice of examples seems to indicate that one may cover only things that are fit for use on the Festival, as opposed to objects such as bricks, which are muktze. The Gemara rejects this proof: With what are we dealing here? With jugs that contain wine and oil that are untithed, which are not fit for Festival use and are therefore muktze. And the same would be true for bricks.

הָכִי נָמֵי מִסְתַּבְּרָא, דְּאִי סָלְקָא דַעְתָּךְ כַּדֵּי יַיִן וְכַדֵּי שֶׁמֶן דְּהֶתֵּירָא, הָא תְּנָא לֵיהּ רֵישָׁא פֵּירוֹת?

The Gemara goes further: So, too, it is in fact more reasonable that this is the case, as if it enters your mind that the mishna is referring to jugs of wine and jugs of oil containing permitted liquids, didn’t the tanna already teach in the first clause of this part of the mishna that it is permitted to cover produce? What new information would be added by specifying jugs as well?

כַּדֵּי יַיִן וְכַדֵּי שֶׁמֶן אִצְטְרִיכָא לֵיהּ, סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ אָמֵינָא: לְהֶפְסֵד מְרוּבֶּה — חָשְׁשׁוּ, לְהֶפְסֵד מוּעָט — לֹא חָשְׁשׁוּ, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara rejects this assertion. It is possible that the mishna is referring specifically to jugs containing permitted liquids. Nevertheless, it was necessary for the tanna to add the example of jugs of wine and jugs of oil, as it could enter your mind to say that the Sages were concerned over a substantial loss, such as of produce, which can be ruined by drops of rain that leak on it. But with regard to a minor loss, such as drops of rain falling into a wine jug or an oil jug, they were not concerned, and they did not permit covering them. The mishna therefore teaches us that those may be covered as well.

תְּנַן: נוֹתְנִין כְּלִי תַּחַת הַדֶּלֶף בְּשַׁבָּת. בְּדֶלֶף הָרָאוּי.

The Gemara raises objections against Rabbi Yitzḥak’s view: We learned in the mishna: One may place a vessel beneath a leak on Shabbat. It is permitted, then, to bring a bucket for the purpose of containing the water leaking into the house, although that water is ostensibly not fit for drinking and is therefore muktze. The Gemara rejects this objection: The case in the mishna is of leakage of water that is in fact fit to be drunk, at least by animals, and is consequently fit for Festival use.

תָּא שְׁמַע: פּוֹרְסִין מַחְצֶלֶת עַל גַּבֵּי לְבֵנִים בְּשַׁבָּת! דְּאִיַּיתּוּר מִבִּנְיָנָא, דַּחֲזֵי לְמִזְגֵּא עֲלַיְיהוּ.

Come and hear another objection from a baraita: One may spread a mat over bricks on Shabbat to protect against rain. The baraita explicitly permits covering bricks, which Rabbi Yitzḥak prohibited. The Gemara rejects this argument: This baraita is referring to bricks that were left over from building and are no longer designated for use in building, and which are consequently fit for use on the Festival by sitting on them.

תָּא שְׁמַע: פּוֹרְסִין מַחְצֶלֶת עַל גַּבֵּי אֲבָנִים בְּשַׁבָּת! בַּאֲבָנִים מְקוּרְזָלוֹת, דְּחַזְיָין לְבֵית הַכִּסֵּא.

Come and hear another objection. It was taught in a baraita: One may spread a mat over stones on Shabbat, although stones are muktze. The Gemara responds: That baraita is speaking not of ordinary stones but of rounded [mekurzalot] stones, which are fit for use in personal hygiene in the lavatory on Shabbat, and are therefore not muktze.

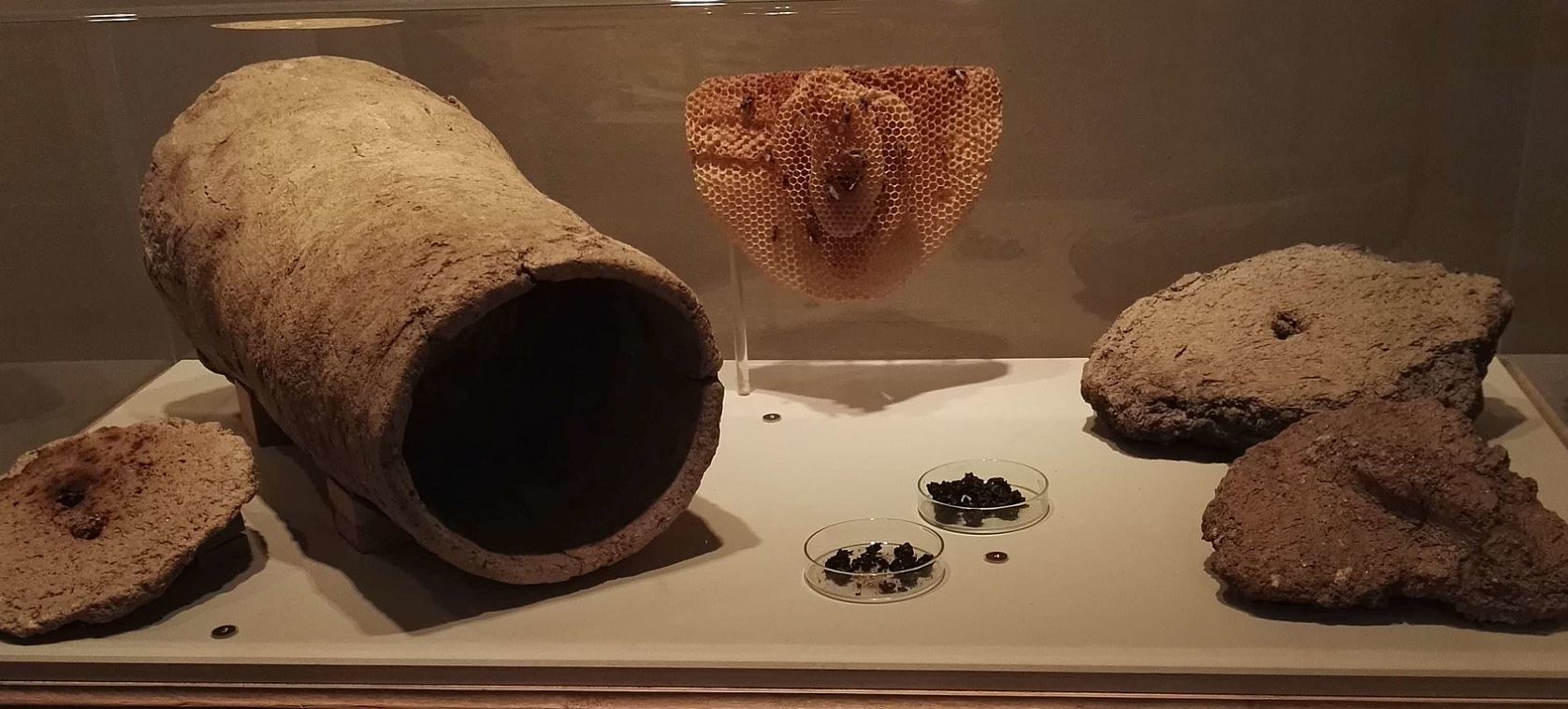

תָּא שְׁמַע: פּוֹרְסִין מַחְצֶלֶת עַל גַּבֵּי כַּוֶּרֶת דְּבוֹרִים בְּשַׁבָּת, בַּחַמָּה — מִפְּנֵי הַחַמָּה, וּבַגְּשָׁמִים — מִפְּנֵי הַגְּשָׁמִים, וּבִלְבַד שֶׁלֹּא יִתְכַּוֵּין לָצוּד! הָתָם נָמֵי, דְּאִיכָּא דְּבַשׁ.

Come and hear an objection from a different source. One may spread a mat over a beehive on Shabbat to protect it from the elements, in the sun due to the sun, and in the rain due to the rain, provided he does not have the intent to trap the bees inside by covering the hive, as trapping is prohibited on Shabbat. A beehive and its bees are not fit for Shabbat use, yet it is permitted to handle a mat in order to cover the hive. The Gemara rejects this: There, too, the reference is to an item that is fit for Shabbat use, as it is discussing a hive when there is honey in it, which can be eaten on Shabbat. It is therefore permitted to handle the mat for the sake of the honey.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב עוּקְבָא מִמֵּישָׁן לְרַב אָשֵׁי: הָתִינַח בִּימוֹת הַחַמָּה, דְּאִיכָּא דְּבַשׁ. בִּימוֹת הַגְּשָׁמִים, מַאי אִיכָּא לְמֵימַר? לֹא נִצְרְכָא אֶלָּא לְאוֹתָן שְׁתֵּי חַלּוֹת. אוֹתָן שְׁתֵּי חַלּוֹת מוּקְצוֹת הֵן! הָכָא בְּמַאי עָסְקִינַן — שֶׁחִשֵּׁב עֲלֵיהֶם.

Rav Ukva from Meishan said to Rav Ashi: This explanation works out well with regard to the summer, when there is honey, but in the rainy season, when there is no honey in beehives, what can be said? The baraita explicitly mentioned the two phrases in the sun and in the rain. The Gemara answers: This halakha is necessary only for those two honeycombs left in the beehive in the winter to sustain the bees. The Gemara questions this: Are those two honeycombs not muktze, as they have clearly been left for the sake of the bees, and not to be used by humans? The Gemara replies: With what case are we dealing here? This is a case when the beekeeper had in mind before the Festival that he was going to take them from the bees and eat them himself.

אֲבָל לֹא חִשֵּׁב עֲלֵיהֶם מַאי — אָסוּר? אַדְּתָנֵי וּבִלְבַד שֶׁלֹּא יִתְכַּוֵּין לָצוּד, לִפְלוֹג וְלִתְנֵי בְּדִידַהּ: בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים — שֶׁחִשֵּׁב עֲלֵיהֶן, אֲבָל לֹא חִשֵּׁב עֲלֵיהֶם — אָסוּר!

The Gemara raises an objection to this interpretation. But if he did not have in mind to take them for himself, what would be the halakha? Wouldn’t it be prohibited to spread a mat over the hive? If so, when the baraita goes on to specify that sometimes it is prohibited to cover the hive, rather than teaching: As long as he does not have the intent to trap the bees, introducing a totally new factor into the discussion, let it make a distinction within the case itself by saying: In what case is this statement said, that the beehive may be covered? When he had in mind beforehand to take the honeycombs; but if he did not have in mind to take them, it is prohibited.

הָכִי קָאָמַר: אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁחִשֵּׁב עֲלֵיהֶן — וּבִלְבַד שֶׁלֹּא יִתְכַּוֵּין לָצוּד.

The Gemara responds: This is what the tanna is saying: Even if he had in mind to take the honeycombs, so that there is no problem of the hive’s being muktze, it is still permitted to cover it provided he does not have intent to trap the bees.

בְּמַאי אוֹקֵימְתָּא — כְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה, דְּאִית לֵיהּ מוּקְצֶה? אֵימָא סֵיפָא: וּבִלְבַד שֶׁלֹּא יִתְכַּוֵּין לָצוּד — אֲתָאן לְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן, דְּאָמַר: דָּבָר שֶׁאֵין מִתְכַּוֵּין מוּתָּר!

The Gemara raises a further objection against this interpretation of the baraita. In what manner did you establish and explain this baraita? In accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda, who, in disagreement with Rabbi Shimon, holds that the halakhot of muktze apply. But now say the latter clause of the baraita: Provided he does not have the intent to trap. This indicates that even though the bees may be trapped in the process of covering, it is permitted if this was not his intention. If so, we have come to the opinion of Rabbi Shimon, who, in disagreement with Rabbi Yehuda, said: An unintentional act is permitted even though it leads inadvertently to a prohibited result. This interpretation of the baraita is internally conflicted, half in accordance with Rabbi Yehuda and half in accordance with Rabbi Shimon.

וְתִסְבְּרָא דְּרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן? וְהָא אַבָּיֵי וְרָבָא דְּאָמְרִי תַּרְוַיְיהוּ: מוֹדֶה רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בִּפְסִיק רֵישֵׁיהּ וְלָא יְמוּת!

The Gemara rejects this argument. And how can you understand that the baraita follows the view of Rabbi Shimon at all? But didn’t Abaye and Rava both say: Rabbi Shimon concedes that even an unintentional act is prohibited in a case of: Cut off its head and will it not die? In this case the person covering the hive with a mat inevitably traps the bees, even if he does not have intent to do so, and this act should be prohibited even by Rabbi Shimon.

לְעוֹלָם כּוּלַּהּ רַבִּי יְהוּדָה הִיא, וְהָכָא בְּמַאי עָסְקִינַן — דְּאִית בֵּיהּ כַּוֵּי. וְלָא תֵּימָא לְרַבִּי יְהוּדָה, וּבִלְבַד שֶׁלֹּא יִתְכַּוֵּין לָצוּד,

Rather, actually all of the baraita is in accordance with Rabbi Yehuda, and with what case are we dealing here? With a beehive that has windows, i.e., small openings, besides the main opening on top, so that some of the windows remain uncovered and covering the hive does not inevitably trap the bees. And in the baraita you should not say, according to Rabbi Yehuda: Provided he does not have intent to trap the bees, which would imply that the deciding factor is the intention of the one who covers them,

אֶלָּא אֵימָא: וּבִלְבַד שֶׁלֹּא יַעֲשֶׂנָּה מְצוּדָה. פְּשִׁיטָא! מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: בְּמִינוֹ נִצּוֹד — אָסוּר, שֶׁלֹּא בְּמִינוֹ נִצּוֹד — מוּתָּר, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

but rather say the following: Provided he does not make it a trap as he covers it, i.e., as long as he takes care not to cover all the openings. The Gemara questions this: But it is obvious that it is prohibited to directly trap bees on Shabbat; why would the baraita mention it? The Gemara responds: It does inform us of something that is not obvious: Lest you say: An animal whose type is generally trapped and hunted by people for some purpose is prohibited to be trapped on Shabbat, whereas an animal whose type is not generally trapped, such as a bee, is permitted to be trapped even ab initio, as this is not considered to be the normal manner of hunting. The baraita therefore teaches us that one may not in fact trap bees.

רַב אָשֵׁי אָמַר: מִי קָתָנֵי בִּימוֹת הַחַמָּה וּבִימוֹת הַגְּשָׁמִים? בַּחַמָּה מִפְּנֵי הַחַמָּה וּבַגְּשָׁמִים מִפְּנֵי הַגְּשָׁמִים קָתָנֵי — בְּיוֹמֵי נִיסָן וּבְיוֹמֵי תִשְׁרֵי, דְּאִיכָּא חַמָּה, וְאִיכָּא גְּשָׁמִים, וְאִיכָּא דְּבַשׁ.

Rav Ashi said a different elucidation: Is it taught in the baraita: In the summer, and: In the rainy season? No, it is taught: In the sun due to the sun and in the rain due to the rain. The baraita speaks not of the summer and the rainy season, but of the spring days of Nisan and the autumn days of Tishrei, when there is sometimes sun and there is sometimes rain, and when there is also honey in the hive. It is possible, then, that the baraita permits covering the hive during these seasons because of the honey that is in it, as initially proposed.

וְנוֹתְנִין כְּלִי תַּחַת הַדֶּלֶף בְּשַׁבָּת. תָּנָא: אִם נִתְמַלֵּא הַכְּלִי — שׁוֹפֵךְ וְשׁוֹנֶה, וְאֵינוֹ נִמְנָע.

§ It was taught in the mishna: And one may place a vessel beneath a leak in order to catch the water on Shabbat. A Sage taught in a baraita: If the vessel became full with the leaking water, he may pour out its contents, place the vessel back under the leak, and repeat the entire process if necessary, and he need not refrain from doing so.

בֵּי רִחְיָא דְּאַבָּיֵי דְּלוּף. אֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּרַבָּה, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: זִיל עַיְּילֵיהּ לְפוּרְיָךְ לְהָתָם, דְּלֶהֱוֵי כִּגְרָף שֶׁל רְעִי, וְאַפְּקֵיהּ.

The Gemara relates: Abaye’s millhouse once developed a leak on Shabbat. Abaye was concerned about the potential damage to the millstones, which were made partly of clay and which would become ruined from the leaking water, and he did not have enough buckets to catch all the water without emptying and refilling them. But the water was unfit for drinking and was therefore muktze and could not be removed. Abaye came before Rabba to ask him how to proceed. Rabba said to him: Go and bring your bed into the millhouse, so that the dirty water will be considered like a container of excrement, which, despite being muktze, may be removed from one’s presence due to its repulsive nature, and then remove the water.

יָתֵיב אַבָּיֵי וְקָא קַשְׁיָא לֵיהּ: וְכִי עוֹשִׂין גְּרָף שֶׁל רְעִי לְכַתְּחִלָּה? אַדְּהָכִי נְפַל בֵּי רִחְיָא דְאַבָּיֵי. אָמַר: תֵּיתֵי לִי דַּעֲבַרִי אַדְּמַר.

Abaye sat and examined the matter and posed a difficulty: And may one initiate a situation of a container of excrement, i.e., may one intentionally place any repulsive matter into a situation which will bother him and will then have to be removed, ab initio? In the meantime, as he was deliberating the issue, Abaye’s millhouse collapsed. He said: I had this coming to me for having gone against the words of my master, Rabba, by not following his ruling unquestioningly.

אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: גְּרָף שֶׁל רְעִי וְעָבִיט שֶׁל מֵימֵי רַגְלַיִם — מוּתָּר לְהוֹצִיאָן לָאַשְׁפָּה, וּכְשֶׁהוּא מַחְזִירוֹ — נוֹתֵן בּוֹ מַיִם וּמַחְזִירוֹ.

Shmuel said: With regard to a container of excrement and a container of urine, it is permitted to remove them on Shabbat to a garbage heap. And when he returns the container to the house he must place water in it first and then return it, for it is prohibited to carry these containers alone, as their foul odor makes them muktze due to their repulsive nature.

סְבוּר מִינַּהּ: גְּרָף שֶׁל רְעִי, אַגַּב מָנָא — אִין, בִּפְנֵי עַצְמוֹ — לָא. תָּא שְׁמַע: דְּהָהוּא עַכְבַּרְתָּא דְּאִשְׁתְּכַח בֵּי אִסְפַּרְמָקֵי דְּרַב אָשֵׁי. אֲמַר לְהוּ רַב אָשֵׁי: נִקְטֻהּ בְּצוּצִיתֵהּ וְאַפְּקוּהּ.

Some Sages at first understood from the wording of Shmuel’s statement that with regard to removing a container of excrement on account of the vessel, i.e., along with its vessel: Yes, this is permitted; but to remove the excrement by itself, without a vessel containing it: No, this is prohibited. The Gemara counters this conclusion with the following story: Come and hear that a certain dead mouse was discovered in Rav Ashi’s storeroom for spices [isparmekei]. Rav Ashi said to them: Take hold of it by its tail and remove it. This shows that repulsive matter may be removed even directly.

מַתְנִי׳ כׇּל שֶׁחַיָּיבִין עָלָיו מִשּׁוּם שְׁבוּת, מִשּׁוּם רְשׁוּת, מִשּׁוּם מִצְוָה, בְּשַׁבָּת — חַיָּיבִין עָלָיו בְּיוֹם טוֹב.

MISHNA: Any act for which one is liable due to a rabbinic decree made to enhance the character of Shabbat as a day of rest [shevut]; or if it is notable because it is optional, i.e., it involves an aspect of a mitzva but is not a complete mitzva; or if it is notable because it is a full-fledged mitzva, if it is prohibited on Shabbat, one is liable for it on a Festival as well.

וְאֵלּוּ הֵן מִשּׁוּם שְׁבוּת: לֹא עוֹלִין בָּאִילָן, וְלֹא רוֹכְבִין עַל גַּבֵּי בְּהֵמָה, וְלֹא שָׁטִין עַל פְּנֵי הַמַּיִם, וְלֹא מְטַפְּחִין וְלֹא מְסַפְּקִין וְלֹא מְרַקְּדִין.

And these are the acts prohibited by the Sages as shevut: One may not climb a tree on Shabbat, nor ride on an animal, nor swim in the water, nor clap his hands together, nor clap his hand on the thigh, nor dance.

וְאֵלּוּ הֵן מִשּׁוּם רְשׁוּת: לֹא דָּנִין, וְלֹא מְקַדְּשִׁין, וְלֹא חוֹלְצִין, וְלֹא מְיַבְּמִין.

And the following are acts that are prohibited on Shabbat and are notable because they are optional, i.e., which involve an aspect of a mitzva but are not complete mitzvot: One may not judge, nor betroth a woman, nor perform ḥalitza, which is done in lieu of levirate marriage, nor perform levirate marriage.

וְאֵלּוּ הֵן מִשּׁוּם מִצְוָה: לֹא מַקְדִּישִׁין, וְלֹא מַעֲרִיכִין, וְלֹא מַחֲרִימִין, וְלֹא מַגְבִּיהִין תְּרוּמָה וּמַעֲשֵׂר.

And the following are prohibited on Shabbat despite the fact that they are notable because of the full-fledged mitzva involved in them: One may not consecrate, nor take a valuation vow (see Leviticus 27), nor consecrate objects for use by the priests or the Temple, nor separate teruma and tithes from produce.

כׇּל אֵלּוּ בְּיוֹם טוֹב אָמְרוּ, קַל וָחוֹמֶר בַּשַּׁבָּת. אֵין בֵּין יוֹם טוֹב לַשַּׁבָּת אֶלָּא אוֹכֶל נֶפֶשׁ בִּלְבָד.

The Sages spoke of all these acts being prohibited even with regard to a Festival; all the more so are they prohibited on Shabbat. The general principle is: There is no difference between a Festival and Shabbat, except for work involving preparation of food alone, which is permitted on a Festival but prohibited on Shabbat.

גְּמָ׳ לֹא עוֹלִין בָּאִילָן — גְּזֵרָה שֶׁמָּא יִתְלוֹשׁ.

GEMARA: The Gemara clarifies the reasons for each of these halakhot: One may not climb a tree. This is a decree that was made lest one detach branches or leaves as he climbs, thereby transgressing the prohibited labor of reaping.

וְלֹא רוֹכְבִין עַל גַּבֵּי בְּהֵמָה — גְּזֵרָה שֶׁמָּא יֵצֵא חוּץ לַתְּחוּם. שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ תְּחוּמִין דְּאוֹרָיְיתָא! אֶלָּא: גְּזֵרָה שֶׁמָּא יַחְתּוֹךְ זְמוֹרָה.

Nor ride on an animal: This is a decree that was made lest one go beyond the Shabbat limit on the animal. The Gemara asks: Can one then learn from here that the prohibition against venturing beyond the Shabbat limits, which applies also to Festivals, is by Torah law? If the prohibition with regard to the Shabbat limit were rabbinic, the Sages would not have reinforced it with the additional decree against riding an animal. It is known that this is a matter of dispute; in light of this explanation of the mishna it would be a proof that Shabbat boundaries are of Torah origin. Rather, give a different reason for the prohibition: It is a decree that was made lest one cut off a branch to use as a riding switch, and thereby perform the labor of reaping, which is prohibited by Torah law.

וְלֹא שָׁטִין עַל פְּנֵי הַמַּיִם — גְּזֵרָה שֶׁמָּא יַעֲשֶׂה חָבִית שֶׁל שַׁיָּיטִין.

Nor swim in the water: This is a decree that was made lest one make a swimmer’s barrel, i.e., an improvised flotation device used to teach beginners how to swim.

וְלֹא מְטַפְּחִין וְלֹא מְסַפְּקִין וְלֹא מְרַקְּדִין — גְּזֵרָה שֶׁמָּא יְתַקֵּן כְּלֵי שִׁיר.

Nor clap one’s hands together, nor clap his hand on the thigh, nor dance: All of these are prohibited due to a decree that was made lest one fashion a musical instrument to accompany his clapping or dancing.

וְאֵלּוּ הֵן מִשּׁוּם רְשׁוּת: לֹא דָּנִין. וְהָא מִצְוָה קָעָבֵיד! לָא צְרִיכָא, דְּאִיכָּא דַּעֲדִיף מִינֵּיהּ.

§ It was taught in the mishna: And the following are acts that are prohibited on Shabbat and are notable because they are optional, i.e., which involve an aspect of a mitzva but are not complete mitzvot: One may not judge. The Gemara asks: But doesn’t one perform a full-fledged mitzva by acting as a judge in a court? Why is it categorized as optional rather than as a full-fledged mitzva? The Gemara answers: No, it is necessary for the mishna to categorize it as optional, as it is speaking of a case where there is another person who is more qualified than he. Since the other person can judge even better, it is not considered an absolute mitzva for the first one to judge.

וְלֹא מְקַדְּשִׁין. וְהָא מִצְוָה קָעָבֵיד! לָא צְרִיכָא,

§ Nor betroth a woman: The Gemara asks: Why is this categorized as optional, indicating that it is not a full-fledged mitzva? But doesn’t one perform a full-fledged mitzva when he marries, as this enables him to fulfill the mitzva to be fruitful and multiply? The Gemara answers: No, it is necessary for the mishna to categorize it as optional,