If sanctified items are sold, what can be done with the money. There is a hierarchy of sanctified items and one can only go up the list, not down. Does the public square where prayers take place on a public fast have sanctity or since it is not used permanently, it does not? A shul in a city is considered owned by many people, even those not from the town, and therefore one cannot sell it as it belongs to the public. Why was Rav Ashi’s shul in Mata Mechasia an exception to this rule? A contradiction to this rule is raised from a braita regarding the sale of a shul in Jerusalem. Why was the law different there? Another question is raised from a tannaitic debate regarding laws of a leperous house in Jerusalem – can it become leperous as it is a private space and only the Temple is not or can it not become leprous as it is all considered public space? If one holds that only the Temple is public, shuls are private! Perhaps what was meant was “holy spaces” and not only the Temple. The root of that debate is whether Jerusalem was divided between Benjamin and Judah or didn’t belong to any particular tribe. The Gemara brings another tannaitic debate on that topic – one opinion holds that the Temple was divided between Benjamin and Judah – which parts belonged to who? Where is there a reference to this in the Torah? The other holds that one cannot rent out space in Jerusalem when people come to the Temple for aliya laregel as the space is owned by all. In that case, what was customarily taken by the hosts as compensation since they couldn’t charge rent? What can be derived from here as good advice for one who is a guest in another’s house? Even though sanctified items cannot be sold for something of lesser sanctity, there is an exception to the rule – if it is stipulated by seven people who are in charge of communal activities for the city and in front of the people of the city. It is forbidden to take apart bricks or beams from an old shul and put them in a new shul. Why? If one sells a shul, the money becomes sanctified and the sanctity leaves the shul and the space can be used for other lesser things. But can it be rented? Is the same true for the bricks and other parts? On what does it depend? If the shul is given as a gift, does the sanctity leave the space? There are different levels of sanctity to items that are used for a mitzva and items that are used for a sanctified item. What falls into which category and can those items be thrown away or do they need to be buried? What can be done with a safer Torah that has fallen apart?

Megillah

Masechet Megilah is sponsored by Jordana and Kalman Schoor on behalf of their daughter Daria Esther who is completing Masechet Megilla in honor of her Bat Mitzva. Mazal tov!

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Today’s daily daf tools:

Megillah

Masechet Megilah is sponsored by Jordana and Kalman Schoor on behalf of their daughter Daria Esther who is completing Masechet Megilla in honor of her Bat Mitzva. Mazal tov!

Today’s daily daf tools:

Delve Deeper

Broaden your understanding of the topics on this daf with classes and podcasts from top women Talmud scholars.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

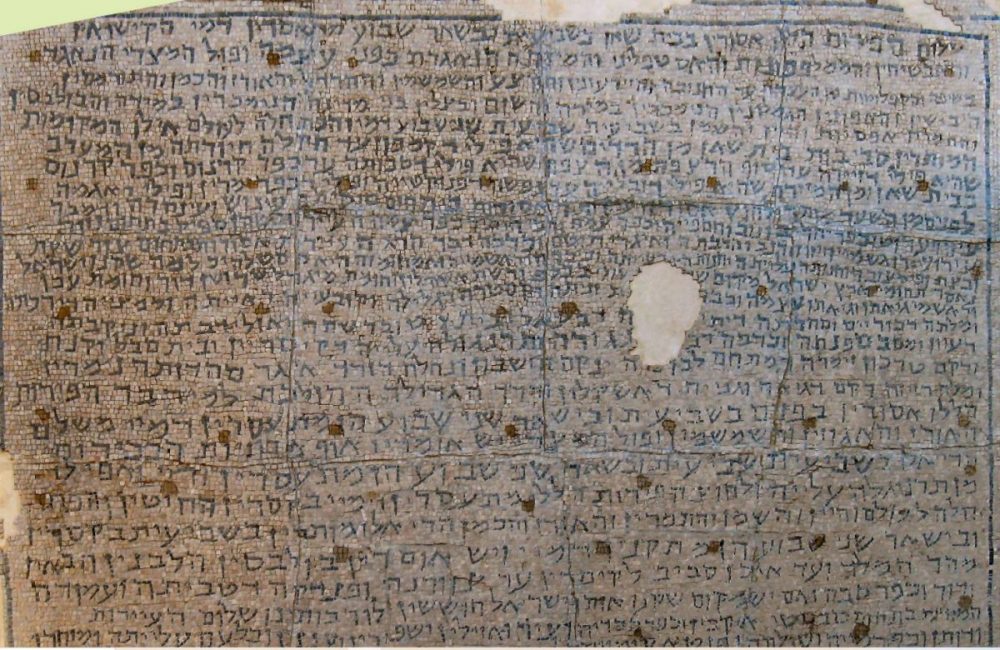

Megillah 26

יִקְחוּ סְפָרִים. סְפָרִים — לוֹקְחִין תּוֹרָה.

they may purchase scrolls of the Prophets and the Writings. If they sold scrolls of the Prophets and Writings, they may purchase a Torah scroll.

אֲבָל אִם מָכְרוּ תּוֹרָה — לֹא יִקְחוּ סְפָרִים. סְפָרִים — לֹא יִקְחוּ מִטְפָּחוֹת. מִטְפָּחוֹת — לֹא יִקְחוּ תֵּיבָה. תֵּיבָה — לֹא יִקְחוּ בֵּית הַכְּנֶסֶת. בֵּית הַכְּנֶסֶת — לֹא יִקְחוּ אֶת הָרְחוֹב.

However, the proceeds of a sale of a sacred item may not be used to purchase an item of a lesser degree of sanctity. Therefore, if they sold a Torah scroll, they may not use the proceeds to purchase scrolls of the Prophets and the Writings. If they sold scrolls of the Prophets and Writings, they may not purchase wrapping cloths. If they sold wrapping cloths, they may not purchase an ark. If they sold an ark, they may not purchase a synagogue. If they sold a synagogue, they may not purchase a town square.

וְכֵן בְּמוֹתְרֵיהֶן.

And similarly, the same limitation applies to any surplus funds from the sale of sacred items, i.e., if after selling an item and purchasing something of a greater degree of sanctity there remain additional, unused funds, the leftover funds are subject to the same principle and may be used to purchase only something of a degree of sanctity greater than that of the original item.

גְּמָ׳ בְּנֵי הָעִיר שֶׁמָּכְרוּ רְחוֹבָהּ שֶׁל עִיר. אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר בַּר חָנָה אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: זוֹ דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי מְנַחֵם בַּר יוֹסֵי סְתִומְתָּאָה, אֲבָל חֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: הָרְחוֹב אֵין בּוֹ מִשּׁוּם קְדוּשָּׁה.

GEMARA: The mishna states: Residents of a town who sold the town square may purchase a synagogue with the proceeds. Concerning this mishna, Rabba bar bar Ḥana said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: This is the statement of Rabbi Menaḥem bar Yosei, cited unattributed. However, the Rabbis say: The town square does not have any sanctity. Therefore, if it is sold, the residents may use the money from the sale for any purpose.

וְרַבִּי מְנַחֵם בַּר יוֹסֵי, מַאי טַעְמֵיהּ? הוֹאִיל וְהָעָם מִתְפַּלְּלִין בּוֹ בְּתַעֲנִיּוֹת וּבְמַעֲמָדוֹת. וְרַבָּנַן — הַהוּא אַקְרַאי בְּעָלְמָא.

And Rabbi Menaḥem bar Yosei, what is his reason for claiming that the town square has sanctity? Since the people pray in the town square on communal fast days and on non-priestly watches, it is defined as a place of prayer and as such has sanctity. And the Rabbis, why do they disagree? They maintain that use of the town square is merely an irregular occurrence. Consequently, the town square is not to be defined as a place of prayer, and so it has no sanctity.

בֵּית הַכְּנֶסֶת — לוֹקְחִין תֵּיבָה. אָמַר רַבִּי שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר נַחְמָנִי אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹנָתָן: לֹא שָׁנוּ אֶלָּא בֵּית הַכְּנֶסֶת שֶׁל כְּפָרִים, אֲבָל בֵּית הַכְּנֶסֶת שֶׁל כְּרַכִּין, כֵּיוָן דְּמֵעָלְמָא אָתוּ לֵיהּ — לָא מָצוּ מְזַבְּנִי לֵיהּ, דְּהָוֵה לֵיהּ דְּרַבִּים.

§ The mishna states: If they sold a synagogue, they may purchase an ark. The Gemara cites a qualification to this halakha: Rabbi Shmuel bar Naḥmani said that Rabbi Yonatan said: They taught this only with regard to a synagogue of a village, which is considered the property of the residents of that village. However, with regard to a synagogue of a city, since people come to it from the outside world, the residents of the city are not able to sell it, because it is considered to be the property of the public at large and does not belong exclusively to the residents of the city.

אָמַר רַב אָשֵׁי: הַאי בֵּי כְנִישְׁתָּא דְּמָתָא מַחְסֵיָא, אַף עַל גַּב דְּמֵעָלְמָא אָתוּ לַהּ, כֵּיוָן דְּאַדַּעְתָּא דִּידִי קָאָתוּ — אִי בָּעֵינָא מְזַבֵּינְנָא לַהּ.

Rav Ashi said: This synagogue of Mata Meḥasya, although people from the outside world come to it, since they come at my discretion, as I established it, and everything is done there in accordance with my directives, if I wish, I can sell it.

מֵיתִיבִי, אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: מַעֲשֶׂה בְּבֵית הַכְּנֶסֶת שֶׁל טוּרְסִיִּים שֶׁהָיָה בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם שֶׁמְּכָרוּהָ לְרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר וְעָשָׂה בָּהּ כׇּל צְרָכָיו, וְהָא הָתָם דִּכְרַכִּים הֲוָה! הָהִיא, בֵּי כְנִישְׁתָּא זוּטֵי הֲוָה, וְאִינְהוּ עַבְדוּהּ.

The Gemara raises an objection to Rabbi Shmuel bar Naḥmani’s statement, from a baraita: Rabbi Yehuda said: There was an incident involving a synagogue of bronze workers [tursiyyim] that was in Jerusalem, which they sold to Rabbi Eliezer, and he used it for all his own needs. The Gemara asks: But wasn’t the synagogue there one of cities, as Jerusalem is certainly classified as a city; why were they permitted to sell it? The Gemara explains: That one was a small synagogue, and it was the bronze workers themselves who built it. Therefore, it was considered exclusively theirs, and they were permitted to sell it.

מֵיתִיבִי: ״בְּבֵית אֶרֶץ אֲחוּזַּתְכֶם״, אֲחוּזַּתְכֶם מִיטַּמָּא בִּנְגָעִים, וְאֵין יְרוּשָׁלָיִם מִיטַּמָּא בִּנְגָעִים. אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: אֲנִי לֹא שָׁמַעְתִּי אֶלָּא מְקוֹם מִקְדָּשׁ בִּלְבַד.

The Gemara raises an objection from another baraita: The verse states with regard to leprosy of houses: “And I put the plague of leprosy in a house of the land of your possession” (Leviticus 14:34), from which it may be inferred: “Your possession,” i.e., a privately owned house, can become ritually impure with leprosy, but a house in Jerusalem cannot become ritually impure with leprosy, as property there belongs collectively to the Jewish people and is not privately owned. Rabbi Yehuda said: I heard this distinction stated only with regard to the site of the Temple alone, but not with regard to the entire city of Jerusalem.

הָא בָּתֵּי כְנֵסִיּוֹת וּבָתֵּי מִדְרָשׁוֹת מִיטַּמְּאִין, אַמַּאי? הָא דִּכְרַכִּין הָווּ! אֵימָא, אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: אֲנִי לֹא שָׁמַעְתִּי אֶלָּא מְקוֹם מְקוּדָּשׁ בִּלְבַד.

The Gemara explains: From Rabbi Yehuda’s statement, it is apparent that only the site of the Temple cannot become ritually impure, but synagogues and study halls in Jerusalem can become ritually impure. Why should this be true given that they are owned by the city? The Gemara answers: Emend the baraita and say as follows: Rabbi Yehuda said: I heard this distinction stated only with regard to a sacred site, which includes the Temple, synagogues, and study halls.

בְּמַאי קָמִיפַּלְגִי? תַּנָּא קַמָּא סָבַר: לֹא נִתְחַלְּקָה יְרוּשָׁלַיִם לִשְׁבָטִים, וְרַבִּי יְהוּדָה סָבַר: נִתְחַלְּקָה יְרוּשָׁלַיִם לִשְׁבָטִים.

With regard to what principle do the first tanna and Rabbi Yehuda disagree? The first tanna holds that Jerusalem was not apportioned to the tribes, i.e., it was never assigned to any particular tribe, but rather it belongs collectively to the entire nation. And Rabbi Yehuda holds: Jerusalem was apportioned to the tribes, and it is only the site of the Temple itself that belongs collectively to the entire nation.

וּבִפְלוּגְתָּא דְהָנֵי תַנָּאֵי.

The Gemara notes: They each follow a different opinion in the dispute between these tanna’im:

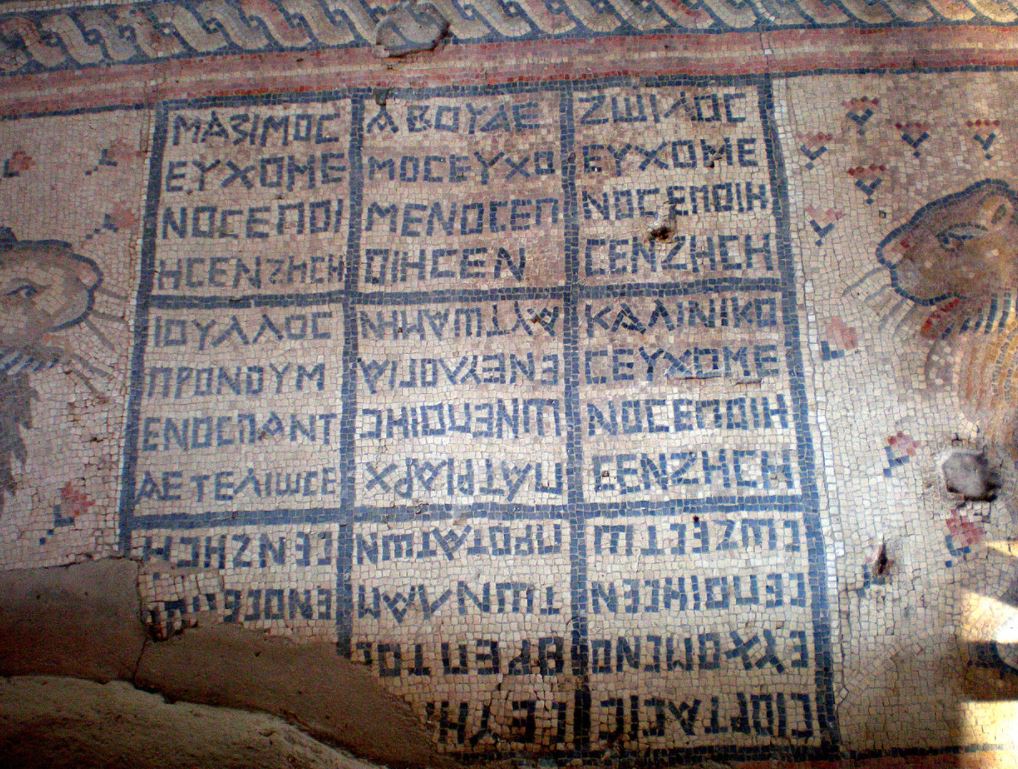

דְּתַנְיָא: מָה הָיָה בְּחֶלְקוֹ שֶׁל יְהוּדָה — הַר הַבַּיִת, הַלְּשָׁכוֹת, וְהָעֲזָרוֹת. וּמָה הָיָה בְּחֶלְקוֹ שֶׁל בִּנְיָמִין — אוּלָם, וְהֵיכָל, וּבֵית קׇדְשֵׁי הַקֳּדָשִׁים.

One tanna holds that Jerusalem was apportioned to the tribes, as it is taught in a baraita: What part of the Temple was in the tribal portion of Judah? The Temple mount, the Temple chambers, and the Temple courtyards. And what was in the tribal portion of Benjamin? The Entrance Hall, the Sanctuary, and the Holy of Holies.

וּרְצוּעָה הָיְתָה יוֹצֵאת מֵחֶלְקוֹ שֶׁל יְהוּדָה וְנִכְנֶסֶת בְּחֶלְקוֹ שֶׁל בִּנְיָמִין, וּבָהּ מִזְבֵּחַ בָּנוּי, וְהָיָה בִּנְיָמִין הַצַּדִּיק מִצְטַעֵר עָלֶיהָ בְּכׇל יוֹם לְבוֹלְעָהּ, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״חוֹפֵף עָלָיו כׇּל הַיּוֹם״, לְפִיכָךְ זָכָה בִּנְיָמִין וְנַעֲשָׂה אוּשְׁפִּיזְכָן לַשְּׁכִינָה.

And a strip of land issued forth from the portion of Judah and entered into the portion of Benjamin, and upon that strip the altar was built, and the tribe of Benjamin, the righteous, would agonize over it every day desiring to absorb it into its portion, due to its unique sanctity, as it is stated in Moses’ blessing to Benjamin: “He covers it throughout the day, and he dwells between his shoulders” (Deuteronomy 33:12). The phrase “covers it” is understood to mean that Benjamin is continually focused upon that site. Therefore, Benjamin was privileged by becoming the host [ushpizekhan] of the Divine Presence, as the Holy of Holies was built in his portion.

וְהַאי תַּנָּא סָבַר לֹא נִתְחַלְּקָה יְרוּשָׁלַיִם לִשְׁבָטִים. דְּתַנְיָא: אֵין מַשְׂכִּירִים בָּתִּים בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁאֵינָן שֶׁלָּהֶן. רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר (בַּר צָדוֹק) אוֹמֵר: אַף לֹא מִטּוֹת. לְפִיכָךְ, עוֹרוֹת קָדָשִׁים — בַּעֲלֵי אוּשְׁפִּיזִין נוֹטְלִין אוֹתָן בִּזְרוֹעַ.

And this other tanna holds that Jerusalem was not apportioned to the tribes, as it is taught in a baraita: One may not rent out houses in Jerusalem, due to the fact that the houses do not belong to those occupying them. Rather, as is true for the entire city, they are owned collectively by the nation. Rabbi Elazar bar Tzadok says: Even beds may not be hired out. Therefore, in the case of the hides of the renter’s offerings that the innkeepers take in lieu of payment, the innkeepers are considered to be taking them by force, as they did not have a right to demand payment.

אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ אוֹרַח אַרְעָא לְמִישְׁבַּק אִינָשׁ גּוּלְפָּא וּמַשְׁכָּא בְּאוּשְׁפִּיזֵיהּ.

Apropos the topic of inns, the Gemara reports: Abaye said: Learn from this baraita that it is proper etiquette for a person to leave his wine flask and the hide of the animal that he slaughtered at his inn, i.e., the inn where he stayed, as a gift for the service he received.

אָמַר רָבָא: לֹא שָׁנוּ אֶלָּא שֶׁלֹּא מָכְרוּ שִׁבְעָה טוֹבֵי הָעִיר בְּמַעֲמַד אַנְשֵׁי הָעִיר, אֲבָל מָכְרוּ שִׁבְעָה טוֹבֵי הָעִיר בְּמַעֲמַד אַנְשֵׁי הָעִיר, אֲפִילּוּ

§ The Gemara returns its discussion of the mishna: Rava said: They taught that there is a limitation on what may be purchased with the proceeds of the sale of a synagogue only when the seven representatives of the town who were appointed to administer the town’s affairs had not sold the synagogue in an assembly of the residents of the town. However, if the seven representatives of the town had sold it in an assembly of the residents of the town, then even

לְמִישְׁתֵּא בֵּיהּ שִׁיכְרָא — שַׁפִּיר דָּמֵי.

to drink beer with the proceeds seems well and is permitted. The seven representatives have the authority to annul the sanctity of the synagogue, and therefore the proceeds of its sale do not retain any sanctity.

רָבִינָא הֲוָה לֵיהּ הָהוּא תִּילָּא דְּבֵי כְנִישְׁתָּא. אֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּרַב אָשֵׁי, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: מַהוּ לְמִיזְרְעֵהּ? אֲמַר לֵיהּ: זִיל זַבְנֵיהּ מִשִּׁבְעָה טוֹבֵי הָעִיר בְּמַעֲמַד אַנְשֵׁי הָעִיר, וְזַרְעֵהּ.

The Gemara relates: Ravina had a certain piece of land on which stood a mound of the ruins of a synagogue. He came before Rav Ashi and said to him: What is the halakha with regard to sowing the land? He said to him: Go, purchase it from the seven representatives of the town in an assembly of the residents of the town, and then you may sow it.

רָמֵי בַּר אַבָּא הֲוָה קָא בָנֵי בֵּי כְנִישְׁתָּא. הֲוָה הָהִיא כְּנִישְׁתָּא עַתִּיקָא, הֲוָה בָּעֵי לְמִיסְתְּרַיהּ וּלְאֵתוֹיֵי לִיבְנֵי וּכְשׁוּרֵי מִינַּהּ וְעַיּוֹלֵי לְהָתָם. יָתֵיב וְקָא מִיבַּעְיָא לֵיהּ הָא דְּרַב חִסְדָּא, דְּאָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא: לָא לִיסְתּוֹר בֵּי כְנִישְׁתָּא עַד דְּבָנֵי בֵּי כְנִישְׁתָּא אַחֲרִיתִי — הָתָם מִשּׁוּם פְּשִׁיעוּתָא, כִּי הַאי גַוְונָא מַאי? אֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּרַב פָּפָּא וַאֲסַר לֵיהּ. לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּרַב הוּנָא וַאֲסַר לֵיהּ.

Rami bar Abba was once building a synagogue. There was a certain old synagogue that he wished to demolish, and bring bricks and beams from it, and bring them to there, to construct a new synagogue. He sat and considered that which Rav Ḥisda said, as Rav Ḥisda said: One should not demolish a synagogue until one has built another synagogue. Rami bar Abba reasoned that Rav Ḥisda’s ruling there is due to a concern of negligence, as perhaps after the first synagogue is demolished, people will be negligent and a new one will never be built. However, in a case like this, where the new synagogue is to be built directly from the materials of the old one, what is the halakha? He came before Rav Pappa to ask his opinion, and he prohibited him from doing so. He then came before Rav Huna, and he also prohibited him from doing so.

אָמַר רָבָא: הַאי בֵּי כְנִישְׁתָּא, חַלּוֹפַהּ וְזַבּוֹנַהּ — שְׁרֵי, אוֹגוֹרַהּ וּמַשְׁכּוֹנַהּ — אֲסִיר. מַאי טַעְמָא: בִּקְדוּשְׁתַּהּ קָאֵי.

Rava said: With regard to this synagogue, exchanging it for a different building or selling it for money is permitted, but renting it out or mortgaging it is prohibited. What is the reason for this? When a synagogue is rented out or mortgaged, it remains in its sacred state. Therefore, it is prohibited to rent it out or mortgage it, because it will then be used for a non-sacred purpose. However, if it is exchanged or sold, its sanctity is transferred to the other building or to the proceeds of the sale, and therefore the old synagogue building may be used for any purpose.

לִיבְנֵי נָמֵי, חַלּוֹפִינְהוּ וְזַבּוֹנִינְהוּ — שְׁרֵי, אוֹזוֹפִינְהוּ — אֲסִיר. הָנֵי מִילֵּי בְּעַתִּיקָתָא, אֲבָל בְּחַדְתָּ[תָ]א — לֵית לַן בַּהּ.

The same halakha is also true of the bricks of a synagogue; exchanging them or selling them is permitted, but renting them out is prohibited. The Gemara comments: This applies to old bricks that have already been part of a synagogue, but as for new bricks that have only been designated to be used in a synagogue, we have no problem with it if they are rented out for a non-sacred purpose.

וַאֲפִילּוּ לְמַאן דְּאָמַר הַזְמָנָה מִילְּתָא הִיא, הָנֵי מִילֵּי כְּגוֹן הָאוֹרֵג בֶּגֶד לַמֵּת. אֲבָל הָכָא, כְּטָווּי לְאָרִיג דָּמֵי, וְלֵיכָּא לְמַאן דְּאָמַר.

And even according to the one who said that mere designation is significant, i.e., although a certain object was not yet used for the designated purpose, the halakhic ramifications of using it for that purpose already take hold, this applies only in a case where it was created from the outset for that purpose, for example, one who weaves a garment to be used as shrouds for a corpse. However, here the bricks are comparable to already spun thread that was then designated to be used to weave burial shrouds. Concerning such designation, where nothing was specifically created for the designated purpose, there is no one who said that the designation is significant.

מַתָּנָה, פְּלִיגִי בַּהּ רַב אַחָא וְרָבִינָא, חַד אָסַר, וְחַד שָׁרֵי. מַאן דְּאָסַר: בְּמַאי תִּפְקַע קְדוּשְׁתַּהּ?! וּמַאן דְּשָׁרֵי: אִי לָאו דַּהֲוָה לֵיהּ הֲנָאָה מִינֵּיהּ — לָא הֲוָה יָהֵיב לֵיהּ, הֲדַר הָוֵה לַיהּ מַתָּנָה כִּזְבִינֵי.

Rav Aḥa and Ravina disagree about whether it is permitted to give away a synagogue as a gift to then be used for a non-sacred purpose. One of them prohibited it, and the other one permitted it. The one who prohibits it says: Is it possible that with this act of giving alone its sanctity is removed? This cannot be the case. Since the synagogue was not exchanged for anything else, there is nothing to which the sanctity may be transferred. Consequently, the synagogue remains sacred. And the one who permitted it does so because he reasons that if the donor did not receive any benefit from giving the synagogue, he would not have given it. Therefore, the gift has reverted to being like a sale, and the sanctity is transferred to the benefit received.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: תַּשְׁמִישֵׁי מִצְוָה — נִזְרָקִין. תַּשְׁמִישֵׁי קְדוּשָּׁה — נִגְנָזִין. וְאֵלּוּ הֵן תַּשְׁמִישֵׁי מִצְוָה: סוּכָּה, לוּלָב, שׁוֹפָר, צִיצִית. וְאֵלּוּ הֵן תַּשְׁמִישֵׁי קְדוּשָּׁה: דְּלוֹסְקְמֵי סְפָרִים, תְּפִילִּין וּמְזוּזוֹת, וְתִיק שֶׁל סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, וְנַרְתִּיק שֶׁל תְּפִילִּין וּרְצוּעוֹתֵיהֶן.

§ The Sages taught in a baraita: Articles used in the performance of a mitzva may be thrown out after use. Although these items were used in the performance of a mitzva, they are not thereby sanctified. However, articles associated with the sanctity of God’s name, i.e. articles on which God’s name is written, and articles that serve an article that has God’s name written on it, even after they are no longer used, must be interred in a respectful manner. And these items are considered articles of a mitzva: A sukka; a lulav; a shofar; and ritual fringes. And these items are considered articles of sanctity: Cases of scrolls, i.e. of Torah scrolls; phylacteries; and mezuzot; and a container for a Torah scroll; and a cover for phylacteries; and their straps.

אָמַר רָבָא, מֵרֵישׁ הֲוָה אָמֵינָא: הַאי כּוּרְסְיָא, תַּשְׁמִישׁ דְּתַשְׁמִישׁ הוּא, וּשְׁרֵי. כֵּיוָן דַּחֲזֵינָא דְּמוֹתְבִי עִלָּוֵיהּ סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, אָמֵינָא: תַּשְׁמִישׁ קְדוּשָּׁה הוּא, וַאֲסִיר.

Rava said: Initially, I used to say that this lectern in the synagogue upon which the Torah is read is only an article of an article of sanctity, as the Torah scroll does not rest directly upon the lectern but rather upon the cloth that covers it. And the halakha is that once an article of an article of sanctity is no longer used, it is permitted to throw it out. However, once I saw that the Torah scroll is sometimes placed directly upon the lectern without an intervening cloth. I said that it is an article used directly for items of sanctity, and as such it is prohibited to simply discard it after use.

וְאָמַר רָבָא, מֵרֵישׁ הֲוָה אָמֵינָא: הַאי פְּרִיסָא, תַּשְׁמִישׁ דְּתַשְׁמִישׁ הוּא. כֵּיוָן דַּחֲזֵינָא דְּעָיְיפִי לֵיהּ וּמַנְּחִי סִיפְרָא עִלָּוֵיהּ, אָמֵינָא: תַּשְׁמִישׁ קְדוּשָּׁה הוּא, וַאֲסִיר.

And Rava similarly said: Initially, I used to say that this curtain, which is placed at the opening to the ark as a decoration, is only an article of an article of sanctity, as it serves to beautify the ark but is not directly used for the Torah scroll. However, once I saw that sometimes the curtain is folded over and a Torah scroll is placed upon it. I said that it is an article used directly for items of sanctity and as such it is prohibited to simply discard it after use.

וְאָמַר רָבָא: הַאי תֵּיבוּתָא דְּאִירְפַט, מִיעְבְּדַהּ תֵּיבָה זוּטַרְתִּי — שְׁרֵי, כּוּרְסְיָיא — אֲסִיר. וְאָמַר רָבָא: הַאי פְּרִיסָא דִּבְלָה, לְמִיעְבְּדֵיהּ פְּרִיסָא לְסִפְרֵי — שְׁרֵי, לְחוּמְשִׁין — אֲסִיר.

And Rava further said: With regard to this ark that has fallen apart, constructing a smaller ark from its materials is permitted, as both have the same level of sanctity, but to use the materials to construct a lectern is prohibited because the lectern has a lesser degree of sanctity. And Rava similarly said: With regard to this curtain used to decorate an ark that has become worn out, to fashion it into a wrapping cloth for Torah scrolls is permitted, but to fashion it into a wrapping cloth for a scroll of one of the five books of the Torah is prohibited.

וְאָמַר רָבָא: הָנֵי זְבִילֵי דְחוּמָּשֵׁי וְקַמְטְרֵי דְסִפְרֵי — תַּשְׁמִישׁ קְדוּשָּׁה נִינְהוּ, וְנִגְנָזִין. פְּשִׁיטָא! מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: הָנֵי לָאו לְכָבוֹד עֲבִידָן, לְנַטּוֹרֵי בְּעָלְמָא עֲבִידִי, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

And Rava also said: With regard to these cases for storing scrolls of one of the five books of the Torah and sacks for storing Torah scrolls, they are classified as articles of sanctity. Therefore, they are to be interred when they are no longer in use. The Gemara asks: Isn’t that obvious? The Gemara answers: Lest you say that since these items are not made for the honor of the scrolls but rather are made merely to provide protection, they should not be classified as articles of sanctity, Rava therefore teaches us that although they are indeed made to protect the scrolls, they also provide honor and are therefore to be classified as articles of sanctity.

הָהוּא בֵּי כְנִישְׁתָּא (דִּיהוּדָאֵי) [דְּ]רוֹמָאֵי דַּהֲוָה פְּתִיחַ לְהָהוּא אִידְּרוֹנָא דַּהֲוָה מַחֵית בֵּיהּ מֵת, וַהֲווֹ בָּעוּ כָּהֲנֵי לְמֵיעַל לְצַלּוֹיֵי הָתָם. אֲתוֹ, אֲמַרוּ לֵיהּ לְרָבָא. אֲמַר לְהוּ: דַּלּוֹ תֵּיבוּתָא אוֹתְבוּהָ, דְּהָוֵה לֵיהּ כְּלִי עֵץ הֶעָשׂוּי לְנַחַת, וּכְלִי עֵץ הֶעָשׂוּי לְנַחַת אֵינוֹ מְקַבֵּל טוּמְאָה וְחוֹצֵץ בִּפְנֵי הַטּוּמְאָה.

The Gemara relates: There was a certain synagogue of the Jews of Rome that opened out into a room in which a corpse was lying, thereby spreading the ritual impurity of the corpse throughout the synagogue. And the priests wished to enter the synagogue in order to pray there. However, it was prohibited for them to do so because a priest may not come in contact with ritual impurity of a corpse. They came and spoke to Rava, about what to do. He said to them: Lift up the ark and put it down in the opening between the two rooms, as it is a wooden utensil that is designated to rest in one place and not be moved from there, and the halakha is that a wooden utensil that is designated to rest is not susceptible to ritual impurity, and therefore it serves as a barrier to prevent ritual impurity from spreading.

אֲמַרוּ לֵיהּ רַבָּנַן לְרָבָא: וְהָא זִמְנִין דִּמְטַלְטְלִי לֵיהּ כִּי מַנַּח סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה עִלָּוֵיהּ, וְהָוֵה לֵיהּ מִיטַּלְטֵל מָלֵא וְרֵיקָם! אִי הָכִי לָא אֶפְשָׁר.

The Rabbis said to Rava: But isn’t the ark sometimes moved when a Torah scroll is still resting inside it, and therefore it is a utensil that is moved both when it is full and when it is empty; such a utensil is susceptible to ritual impurity and cannot prevent ritual impurity from spreading. He said to them: If so, if it is as you claim, then it is not possible to remedy the situation.

אָמַר מָר זוּטְרָא: מִטְפְּחוֹת סְפָרִים שֶׁבָּלוּ — עוֹשִׂין אוֹתָן תַּכְרִיכִין לְמֵת מִצְוָה, וְזוֹ הִיא גְּנִיזָתָן.

Mar Zutra said: With regard to wrapping cloths of Torah scrolls that have become worn out, they may be made into shrouds for a corpse with no one to bury it [met mitzva], and this is their most appropriate manner for being interred.

וְאָמַר רָבָא: סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה שֶׁבָּלָה — גּוֹנְזִין אוֹתוֹ אֵצֶל תַּלְמִיד חָכָם, וַאֲפִילּוּ שׁוֹנֶה הֲלָכוֹת. אָמַר רַב אַחָא בַּר יַעֲקֹב: וּבִכְלִי חֶרֶס, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וּנְתַתָּם בִּכְלִי חָרֶשׂ לְמַעַן יַעַמְדוּ יָמִים רַבִּים״.

And Rava said: A Torah scroll that became worn out is interred and buried next to a Torah scholar, and in this regard, a Torah scholar is defined even as one who only studies the halakhot in the Mishna and the baraitot but is not proficient in their analysis. Rav Aḥa bar Ya’akov said: And when it is buried, it is first placed in an earthenware vessel, as it is stated: “And put them in an earthenware vessel, that they may last for many days” (Jeremiah 32:14).

(וְאָמַר) רַב פַּפִּי מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דְּרָבָא: מִבֵּי כְנִישְׁתָּא לְבֵי רַבָּנַן — שְׁרֵי, מִבֵּי רַבָּנַן לְבֵי כְנִישְׁתָּא — אֲסִיר. וְרַב פָּפָּא מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דְּרָבָא מַתְנִי אִיפְּכָא. אָמַר רַב אַחָא:

§ And Rav Pappi said in the name of Rava: To convert a building from a synagogue into a study hall is permitted, but from a study hall into a synagogue is prohibited, as he holds that a study hall has a higher degree of sanctity than a synagogue. And Rav Pappa in the name of Rava teaches the opposite, as he holds that a synagogue has a higher degree of sanctity than a study hall. Rav Aḥa said: