Nedarim 56

מַתְנִי׳ הַנּוֹדֵר מִן הַבַּיִת — מוּתָּר בַּעֲלִיָּיה, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי מֵאִיר. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: עֲלִיָּיה בִּכְלַל הַבַּיִת. הַנּוֹדֵר מִן עֲלִיָּיה — מוּתָּר בְּבַיִת.

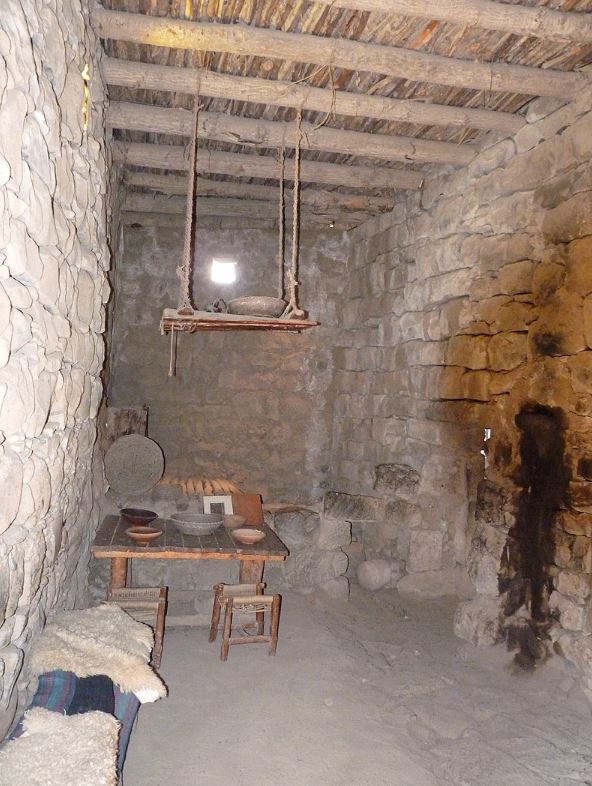

MISHNA: For one who vows that a house is forbidden to him, entry is permitted for him in the upper story of the house; this is the statement of Rabbi Meir. And the Rabbis say: An upper story is included in the house, and therefore, entry is prohibited there as well. However, for one who vows that an upper story is forbidden to him, entry is permitted in the house, as the ground floor is not included in the upper story.

גְּמָ׳ מַאן תְּנָא ״בְּבֵית״ לְרַבּוֹת אֶת הַיָּצִיעַ, ״בְּבֵית״ לְרַבּוֹת אֶת הָעֲלִיָּיה? אָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא: רַבִּי מֵאִיר הִיא, דְּאִי רַבָּנַן, הָאָמְרִי רַבָּנַן: עֲלִיָּיה בִּכְלַל הַבַּיִת, לְמָה לִי קְרָא ״בְּבֵית״ לְרִיבּוּיָא?

GEMARA: The Gemara asks: Who is the tanna who taught with regard to the halakhot of leprosy that in the verse “it appears to me as it were a plague in the house” (Leviticus 14:35), the term “in the house” comes to include the gallery, a half story above the ground floor, and “in the house” comes to include the upper story? Rav Ḥisda said: The tanna is Rabbi Meir, as, if the tanna were the Rabbis, didn’t the Rabbis say that a second story is included in the house? Why then do I need the verse containing the phrase “in the house” to include the second story?

אַבָּיֵי אָמַר: אֲפִילּוּ תֵּימָא רַבָּנַן, בָּעֲיָא קְרָא. דְּסָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ אָמֵינָא ״בְּבֵית אֶרֶץ אֲחֻזַּתְכֶם״ כְּתִיב. דִּמְחַבַּר בְּאַרְעָא — שְׁמֵיהּ בַּיִת, עֲלִיָּיה — הָא לָא מְחַבַּר בְּאַרְעָא.

Abaye said: Even if you would say that the tanna is the Rabbis, they too require a verse to include the second story in this case, as it might enter your mind to say that since it is written: “In a house of the land of your possession” (Leviticus 14:34), only that which is attached to the ground has the status of a house but with regard to a second story, that is not attached to the ground. Even according to the Rabbis, the verse is necessary to prevent the conclusion that the legal status of a second story is not that of a house with regard to leprosy.

כְּמַאן אָזְלָא הָא דְּאָמַר רַב הוּנָא בַּר חִיָּיא מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דְּעוּלָּא: ״בַּיִת בְּבֵיתִי אֲנִי מוֹכֵר לָךְ״ — מַרְאֵהוּ עֲלִיָּיה. טַעְמָא דַּאֲמַר לֵיהּ ״בַּיִת שֶׁבְּבֵיתִי אֲנִי מוֹכֵר לָךְ״, אֲבָל ״בַּיִת״ סְתָם — אֵינוֹ מַרְאֵהוּ עֲלִיָּיה. לֵימָא, רַבִּי מֵאִיר הִיא? אֲפִילּוּ תֵּימָא רַבָּנַן, מַאי ״עֲלִיָּיה״ — מְעוּלָּה שֶׁבַּבָּתִּים.

The Gemara asks: In accordance with whose opinion is that which Rav Huna bar Ḥiyya said in the name of Ulla? If the seller says to the buyer: A house in my house I am selling to you, he may show the buyer that he purchased the second story [aliyya]. The Gemara infers: The reason is that the seller said to him: A house in my house I am selling to you. However, if he sold him a house, unspecified, he may not show him a second story. Let us say that this is the opinion of Rabbi Meir, who states that the second story is not included in the house. The Gemara rejects this claim: Even if you would say that it is in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis, what is the meaning of the term aliyya in this context? It does not mean second story; it means the most outstanding of the houses. Rav Huna bar Ḥiyya said in the name of Ulla that when one says a house in my house, he must show him the most outstanding part of his house. However, if he sold him a house without specification, he may show him a second story.

מַתְנִי׳ הַנּוֹדֵר מִן הַמִּטָּה — מוּתָּר בַּדַּרְגֵּשׁ, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי מֵאִיר. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: דַּרְגֵּשׁ בִּכְלַל מִטָּה. הַנּוֹדֵר מִן הַדַּרְגֵּשׁ — מוּתָּר בַּמִּטָּה.

MISHNA: For one who vows that a bed is forbidden to him, it is permitted to lie in a dargash, which is not commonly called a bed; this is the statement of Rabbi Meir. And the Rabbis say: A dargash is included in the category of a bed. Everyone agrees that for one who vows that a dargash is forbidden to him, it is permitted to lie in a bed.

גְּמָ׳ מַאי דַּרְגֵּשׁ? אָמַר עוּלָּא: עַרְסָא דְגַדָּא. אֲמַרוּ לֵיהּ רַבָּנַן לְעוּלָּא, הָא דִּתְנַן: כְּשֶׁהֵן מַבְרִין אוֹתוֹ, כׇּל הָעָם מְסוּבִּין עַל הָאָרֶץ וְהוּא מֵיסֵב עַל הַדַּרְגֵּשׁ. כּוּלָּהּ שַׁתָּא לָא יָתֵיב עֲלֵהּ, הָהוּא יוֹמָא יָתֵיב עֲלֵהּ? מַתְקֵיף לַהּ רָבִינָא: מִידֵּי דְּהָוֵה אַבָּשָׂר וְיַיִן, דְּכוּלַּהּ שַׁתָּא אִי בָּעֵי — אָכֵיל, וְאִי בָּעֵי — לָא אָכֵיל, הָהוּא יוֹמָא אֲנַן יָהֲבִינַן לֵיהּ!

GEMARA: The Gemara asks: What is a dargash? Ulla said: It is a bed of good fortune, placed in the house as a fortuitous omen, and not designated for sleeping. The Rabbis said to Ulla: That which we learned in a mishna: When the people serve the king the meal of comfort after he buries a relative, all the people recline on the ground and the king reclines on a dargash during the meal. According to your explanation, during the entire year he does not sit on the bed; on that day of the funeral he sits on it? Ravina objects to the question of the Rabbis: This anomaly is just as it is with regard to meat and wine, as throughout the entire year if he wishes he eats them, and if he wishes he does not eat them; on that day of the funeral, we give him meat and wine in the meal of comfort.

אֶלָּא הָא קַשְׁיָא, דְּתַנְיָא: דַּרְגֵּשׁ לֹא הָיָה כּוֹפֵהוּ, אֶלָּא זוֹקְפוֹ. וְאִי אָמְרַתְּ עַרְסָא דְגַדָּא הוּא, וְהָתַנְיָא: הַכּוֹפֶה אֶת מִטָּתוֹ — לֹא מִטָּתוֹ בִּלְבַד הוּא כּוֹפֶה, אֶלָּא כׇּל מִטּוֹת שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ בְּתוֹךְ הַבַּיִת הוּא כּוֹפֶה! הָא לָא קַשְׁיָא,

Rather, this is difficult, as it is taught in a baraita with regard to the custom of overturning the beds in the house of a mourner: With regard to a dargash in his house, the mourner would not overturn it, but he merely stands it on its side. And if you say that a dargash is a bed of fortune, isn’t it taught in a baraita: A mourner who is required to overturn his bed is required to overturn not only his own bed, but to overturn all of the beds that he has inside his house, even those not used for sleeping. Why, then, is he not required to overturn the dargash? The Gemara rejects this contention: This is not difficult;

מִידֵּי דְּהָוֵה אַמִּטָּה הַמְיוּחֶדֶת לְכֵלִים, דְּתַנְיָא: אִם הָיְתָה מִטָּה הַמְיוּחֶדֶת לְכֵלִים — אֵין צָרִיךְ לִכְפּוֹתָהּ.

this is just as it is with regard to the case of a bed designated exclusively for vessels, as it is taught in a baraita: If the bed in a mourner’s house was a bed designated for vessels and not for sleeping, one need not overturn it. The same is true with regard to the bed of fortune. Since it is not for sleeping, one need not overturn it.

אֶלָּא אִי קַשְׁיָא — הָא קַשְׁיָא, דְּתַנְיָא, רַבָּן שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל אוֹמֵר: דַּרְגֵּשׁ — מַתִּיר קַרְבִּיטָיו וְהוּא נוֹפֵל מֵאֵלָיו. וְאִי דַּרְגֵּשׁ עַרְסָא דְגַדָּא הוּא, קַרְבִּיטִין מִי אִית לֵיהּ? כִּי אֲתָא רָבִין, אָמַר: שְׁאֵילְתֵּיהּ לְהָהוּא מֵרַבָּנַן וְרַב תַּחְלִיפָא בַּר מַעְרְבָא שְׁמֵיהּ, דַּהֲוָה שְׁכִיחַ בְּשׁוּקָא דְצַלָּעֵי, וְאָמַר לִי: מַאי דַּרְגֵּשׁ — עַרְסָא דְצַלָּא.

Rather, if defining a dargash as a bed of fortune is difficult, this is difficult, as it is taught in a baraita that Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel says: A mourner need not overturn a dargash; rather, he loosens the loops that connect the straps that support the bedding to the bedframe, and it collapses on its own. And if a dargash is a bed of fortune, does it have loops [karvitin]? When Ravin came from Eretz Yisrael to Babylonia, he said: I asked one of the Sages about the meaning of dargash, and Rav Taḥalifa, from the West, was his name, who frequented the tanners’ market. And he said to me: What is a dargash? It is a leather bed.

אִיתְּמַר, אֵיזֶהוּ מִטָּה וְאֵיזֶהוּ דַּרְגֵּשׁ? אָמַר רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה: מִטָּה — מְסָרְגִין אוֹתָהּ עַל גַּבָּהּ, דַּרְגֵּשׁ — מְסָרְגִין אוֹתוֹ מִגּוּפוֹ. מֵיתִיבִי: כְּלֵי עֵץ מֵאֵימָתַי מְקַבְּלִין טוּמְאָה? הַמִּטָּה וְהָעֲרִיסָה — מִשֶּׁיְּשׁוּפֵם בְּעוֹר הַדָּג. וְאִי מִטָּה מִסְתָּרֶגֶת עַל גַּבָּהּ, לְמָה לִי שִׁיפַת עוֹר הַדָּג?

It was stated: Which is a bed and which is a dargash? Rabbi Yirmeya said: In a bed, one fastens the supporting straps over the bedframe; in a dargash, one fastens the straps through holes in the bedframe itself. The Gemara raises an objection from a mishna in tractate Kelim (16:1): With regard to wooden vessels, from when are they considered finished vessels and susceptible to ritual impurity? A bed and a crib are susceptible from when he smooths them with the skin of a fish. And the objection is: If in a bed the straps are fastened over the bedframe, why do I need smoothing with the skin of a fish? The wood of the bedframe is obscured from view.

אֶלָּא הָא וְהָא מִגּוּפָן. מִטָּה — אַעוֹלֵי וְאַפּוֹקֵי בְּבִזְיָנֵי, דַּרְגֵּשׁ — אַעוֹלֵי וְאַפּוֹקֵי בַּאֲבַקְתָּא.

Rather, with regard to both this, a bed, and that, a dargash, one fastens the straps through holes in the bedframes themselves, and the difference between them is: In a bed, the straps are inserted and extracted through holes in the bedframe; in a dargash, the straps are inserted and extracted through loops attached to the bedframe, as Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel said that one loosens the loops and the bedding falls on its own.

אָמַר רַבִּי יַעֲקֹב בַּר אַחָא אָמַר רַבִּי: מִטָּה שֶׁנַּקְלִיטֶיהָ יוֹצְאִין, זוֹקְפָהּ וְדַיּוֹ. אָמַר רַבִּי יַעֲקֹב בַּר אִידֵּי אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: הֲלָכָה כְּרַבָּן שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל.

Rabbi Ya’akov bar Aḥa said that Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi said: With regard to a bed whose two posts [nakliteha] protrude, rendering its overturning impossible, he stands it on its side, and that is sufficient for him. Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi said that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel with regard to the overturning of a dargash.

מַתְנִי׳ הַנּוֹדֵר מִן הָעִיר — מוּתָּר לִיכָּנֵס לִתְחוּמָהּ שֶׁל עִיר, וְאָסוּר לִיכָּנֵס לְעִיבּוּרָהּ. אֲבָל הַנּוֹדֵר מִן הַבַּיִת — אָסוּר מִן הָאֲגַף וְלִפְנִים.

MISHNA: For one who vows that the city is forbidden to him, it is permitted to enter the Shabbat boundary of that city, the two-thousand-cubit area surrounding the city, and it is prohibited to enter its outskirts, the seventy-cubit area adjacent to the city. However, for one who vows that a house is forbidden to him, it is prohibited to enter only from the doorstop and inward.

גְּמָ׳ מְנָלַן דְּעִיבּוּרָא דְמָתָא כְּמָתָא דָּמֵי? אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״וַיְהִי בִּהְיוֹת יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בִּירִיחוֹ וְגוֹ׳״, מַאי בִּירִיחוֹ? אִילֵּימָא בִּירִיחוֹ מַמָּשׁ, וְהָכְתִיב: ״וִירִיחוֹ סֹגֶרֶת וּמְסֻגֶּרֶת״! אֶלָּא שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ בְּעִיבּוּרָהּ.

GEMARA: The Gemara asks: From where do we derive that the legal status of the outskirts of a city are like that of the city itself? Rabbi Yoḥanan said that it is as the verse states: “And it came to pass when Joshua was in Jericho, that he lifted up his eyes and looked” (Joshua 5:13). What is the meaning of “in Jericho”? If we say that it means in Jericho proper, isn’t it written: “And Jericho was completely shut” (Joshua 6:1)? Rather, learn from here that Joshua was in the outskirts of the city. And although he was in the outskirts, the verse states that he was in Jericho.

אֵימָא אֲפִילּוּ בִּתְחוּמָהּ! הָא כְּתִיב בִּתְחוּמָהּ ״וּמַדֹּתֶם מִחוּץ לָעִיר״.

The Gemara asks: Say that the legal status of one located even in the Shabbat boundary of a city is like that of one inside the town itself, and perhaps although Joshua was merely within the Shabbat boundary, the verse characterizes him as being in Jericho. The Gemara rejects this: Isn’t it written with regard to the boundary of a city: “And you shall measure outside the city…two thousand cubits” (Numbers 35:5)? This indicates that the boundary of a city is considered outside the town and not part of the city itself.

הַנּוֹדֵר מִן הַבַּיִת — אֵינוֹ אָסוּר אֶלָּא מִן הָאֲגַף וְלִפְנִים. אֲבָל מִן הָאֲגַף וְלַחוּץ — לֹא. מֵתִיב רַב מָרִי: ״וְיָצָא הַכֹּהֵן מִן הַבַּיִת״, יָכוֹל יֵלֵךְ לְבֵיתוֹ וְיַסְגִּיר — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״אֶל פֶּתַח הַבָּיִת״. אִי אֶל פֶּתַח הַבָּיִת, יָכוֹל יַעֲמוֹד תַּחַת הַמַּשְׁקוֹף וְיַסְגִּיר — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״מִן הַבַּיִת״, עַד שֶׁיֵּצֵא מִן הַבַּיִת כּוּלּוֹ.

§ We learned in the mishna: For one who vows that a house is forbidden to him, it is prohibited to enter only from the doorstop and inward. The Gemara infers: However, from the doorstop outward, no, it is permitted to enter. Rav Mari raised an objection based on a verse written with regard to leprosy: “And the priest shall go out from the house to the entrance of the house, and he shall quarantine the house” (Leviticus 14:38). And the question was raised in the halakhic midrash: One might have thought that the priest may go to his house and quarantine the leprous house that he examined from there. Therefore, the verse states: “To the entrance of the house” (Leviticus 14:38). If he may go only to the entrance of the house, one might have thought that he may stand beneath the lintel and quarantine the house from there. Therefore, the verse states: “And the priest shall go out from the house,” indicating that he may not quarantine the house until he goes out from the entire house.

הָא כֵּיצַד? עוֹמֵד בְּצַד הַמַּשְׁקוֹף וְיַסְגִּיר. וּמִנַּיִן שֶׁאִם הָלַךְ לְבֵיתוֹ וְהִסְגִּיר, אוֹ שֶׁעָמַד תַּחַת הַשָּׁקוֹף וְהִסְגִּיר, שֶׁהֶסְגֵּירוֹ מוּסְגָּר — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״וְהִסְגִּיר אֶת הַבַּיִת״, מִכׇּל מָקוֹם. שָׁאנֵי גַּבֵּי בַּיִת, דִּכְתִיב: ״מִן הַבַּיִת״, עַד שֶׁיֵּצֵא מִן הַבַּיִת כּוּלּוֹ.

How so? Ab initio, the priest stands outside, alongside the door jamb, and quarantines the house. And from where is it derived that if he went to his house and quarantined the house, or stood beneath the lintel and quarantined the house, that his quarantine is an effective quarantine after the fact? The verse states: “And he shall quarantine the house” (Leviticus 14:38), which means in any case. Apparently, the legal status of the area beneath the lintel is identical to the status inside the house, even if it is beyond the doorstop. The Gemara answers: It is different with regard to a leprous house, as it is written: “And the priest shall go out from the house,” indicating that he cannot quarantine the house until he goes out from the entire house.