This week we enter the realm of the lost: chapter two of Bava Metzia is all about lost objects: what needs to be returned and how owners can claim their property. The law is based on the verses in the Torah that talk about returning lost items to their owner:

“If you see your fellow Israelite’s ox or sheep gone astray, do not ignore it; you must take it back (הָשֵׁ֥ב תְּשִׁיבֵ֖ם) to your peer. . .You shall do the same with that person’s ass; you shall do the same with that person’s garment; and so too shall you do with anything that your fellow Israelite loses (לְכׇל־אֲבֵדַ֥ת אָחִ֛יךָ אֲשֶׁר־תֹּאבַ֥ד ) and you find: you must not remain indifferent.” (Devarim 22:1, 3)

The highlighted Hebrew words, hashev and aveida, return and lost item, are the source for the term commonly used in halacha, hashavat aveida, returning lost objects. Interestingly, most of the instances of the root אבד in Tanakh are about destruction, i.e., permanent loss and not about temporarily misplacing something. For example, the Israelites are commanded אבד תאבדון, destroy completely the sites of the Canaanite idol worshippers (Devarim 12:2). A powerful personal example is Esther’s resolve to go before Achashverosh no matter what the consequences:

לֵךְ֩ כְּנ֨וֹס אֶת־כׇּל־הַיְּהוּדִ֜ים הַֽנִּמְצְאִ֣ים בְּשׁוּשָׁ֗ן וְצ֣וּמוּ עָ֠לַ֠י וְאַל־תֹּאכְל֨וּ וְאַל־תִּשְׁתּ֜וּ שְׁלֹ֤שֶׁת יָמִים֙ לַ֣יְלָה וָי֔וֹם גַּם־אֲנִ֥י וְנַעֲרֹתַ֖י אָצ֣וּם כֵּ֑ן וּבְכֵ֞ן אָב֤וֹא אֶל־הַמֶּ֙לֶךְ֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר לֹֽא־כַדָּ֔ת וְכַאֲשֶׁ֥ר אָבַ֖דְתִּי אָבָֽדְתִּי׃

“Go, assemble all the Jews who live in Shushan, and fast in my behalf; do not eat or drink for three days, night or day. I and my maidens will observe the same fast. Then I shall go to the king, though it is contrary to the law; and if I am to perish, I shall perish!” (Esther 4:16)

The Torah law is meant to ensure that lost objects are not אבד, lost forever, but returned to their owners. As Professor Zeev Safrai points out in his Mishnah commentary, this is part of monetary law, not merely a nice thing to do. The law of the State of Israel also incorporates many (although not all) of the laws of hashavat aveida, requiring finders to seek out losers.

Andy F / TfL lost property office on Baker Street

Besides personal property, many things have famously been lost in Jewish history. The Ark of the Covenant disappeared at the end of First Temple times (https://hadran.org.il/author-post/calling-indiana-jones/) and ten of the twelve Israelite tribes even earlier than that ( https://hadran.org.il/author-post/lost-and-found/). We are still hoping to find the lost Temple vessels, taken as spoils to Rome two millennia ago:

Paolo Villa, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

With the advent of archaeology, some lost items have famously been found. Some are small but wonderful examples of a life lived, like the lost earring found in City of David excavations:

Michelle Levitz

Another example is the seal of Nahmanides found on the road to Akko (https://hadran.org.il/author-post/lover-of-zion/), giving us a physical relic of someone who otherwise is known only through his writings. There are also much more monumental finds: whole cities that we knew about from literature but needed to unearth from the dust. A great example is Zippori (https://hadran.org.il/author-post/unsafe-spaces/).

Outside of Israel, one of the most prominent “found cities” is Nineveh, in the empire of Assyria. Although Nineveh features prominently in the Biblical narrative, its site was unknown for centuries. The first to understand that Mosul, on the banks of the Tigris River, contained the remains of ancient Nineveh was that peripatetic Jew, Benjamin of Tudela, in the 12th century. But no one followed up on his suggestion and only in the mid-19th century was Nineveh “discovered.” A British adventurer and treasure hunter named Austen Henry Layard began to dig up the site in the 1840s with the assistance of local Christian Arab Hormuzd Rassam. The two uncovered amazing treasures, most of which they shipped back to London where today they are displayed in splendor in the British Museum.

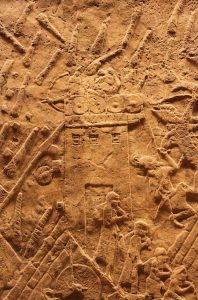

Nineveh was the royal city of Assyrian kings like Tiglat Pileser, Sennacherib and Ashurbanipal. Each built a palace and decorated it lavishly, primarily with enormous reliefs of battle scenes. These served a dual purpose: they were decorative and they ensured that any foreign dignitary who might be considering rebelling against Assyria understood quite clearly what lay in store for him. For Bible scholars the most important relief is the one Sennacherib made after he conquered the Judean town of Lachish. It clearly depicts the Assyrian siege ramp, the Judean counter-ramp and the arrows and catapult stones, all of which were found when Lachish itself was excavated in the 1930s.

Part of Lachish relief

Oren Rozen, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Sennacherib did not only destroy, he also upgraded the city of Nineveh, creating broad streets, canals and building an aqueduct from a site sixty-five kilometers away to bring more water to the city. But it was his grandson Ashurbanipal who left the most lasting legacy. He was a powerful king as well as a cultured scholar. As a book collector he assembled a library of over thirty thousand cuneiform tablets. Among the laws, letters, medical advice, and religious texts are tablets with ancient stories that were seen for the first time here. The stories of the great flood in the Tale of Gilgamesh and the creation of the world in Enuma Elish were mainstays of Mesopotamian culture and the Bible is aware of them and plays off of them. Today they are an inextricable piece of Biblical scholarship yet they were unknown until the late nineteenth century.

Ashurbanipal library tablets, as displayed in the British Museum

Gary Todd, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Nineveh was destroyed and sacked in 612 and the mighty Assyrian empire disappeared, swallowed up by its successor Babylonia. For millennia, the city, and the library, were “lost,” only to be returned to the world by nineteenth century adventurers.

Besides objects and sites, there are lost people as well. Jacob is described as a lost or wandering Aramean ארמי אובד אבי (Devarim 26:5). The Gemara deduces from the verses in Devarim that a lost person must be helped to find his way:

“From where is it derived that the requirement applies even to returning his body, [i.e., helping a lost person find his way]? The verse states: “And you shall restore it to him” (Deuteronomy 22:2), [which can also be translated as: And you shall restore himself to him]” (Bava Kamma 81b).

Today we still have many “lost,” captured by an evil enemy who refuses to return them to their homes and families. We pray for the immediate and safe return of all our hostages to their borders!

Oren Rozen, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons