If one designated birds from one nest and found birds in front of the nest on Yom Tov instead of in the nest, they are forbidden because they may not be the ones he designated. Is it because when there is “majority” and “proximity”, we follow the majority? Rava and Abaye explain the case – each in a different way, each showing that this is not a case where proximity is different than the majority. What does the mishna means when it says that if there are no more chicks in the area, then it can be assumed that what one finds is what was designated? Isn’t it obvious?! Beit Shamai and Beit Hillel disagree on the matter of using a pestle on Shabbat for cutting meat, a permitted activity. Abaye derives from the mishna that only a pestle is forbidden by Beit Shammai, but a wooden anvil would be permitted. There is a slightly different version of Abaye’s opinion. According to the second version, Beit Shamai is not concerned that one will change one’s mind regarding the use of the anvil – however, this contradicts other cases where Beit Shami is concerned one will change one’s mind. What is the difference between the cases? How can one take care of the hide of an animal that is slaughtered on Yom Tov? Can one put it on the floor and people will trample on it? What can be done with the forbidden fats of the animal on Yom Tov? Is it possible to salt a few pieces of meat on a Yom Tov if you only need one for the holiday? Is it possible to remove shutters in a store on Yom Tov to sell items needed for the holiday? Is it possible to return them to their place after, to protect the goods? There is a dispute between Beit Shamai and Beit Hillel on the issue. Ulla counts three cases and Rechava adds a fourth in which something is allowed because of its beginning – in order for people to perform another mitzvah, such as to ensure people will slaughter animals and fulfill the mitzvah of Simchat Yom Tov. Why did Ulla have to indicate these cases – what was not clear in the mishnayot in which all these cases were mentioned? Why did Ulla not mention the case of Rehava? How did Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar understand differently the dispute between Beit Shamai and Beit Hillel regarding the shutters? And in which case did they agree – with/without a hinge? What kind of hinge?

This month’s learning is dedicated to the refuah shleima of our dear friend, Phyllis Hecht, גיטל פעשא בת מאשה רחל by all her many friends who love and admire her. Phyllis’ emuna, strength, and positivity are an inspiration.

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Today’s daily daf tools:

This month’s learning is dedicated to the refuah shleima of our dear friend, Phyllis Hecht, גיטל פעשא בת מאשה רחל by all her many friends who love and admire her. Phyllis’ emuna, strength, and positivity are an inspiration.

Today’s daily daf tools:

Delve Deeper

Broaden your understanding of the topics on this daf with classes and podcasts from top women Talmud scholars.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Beitzah 11

דְּמִתְעַכַּל קִטְרַיְיהוּ.

their knot becomes worn and untied. Consequently, it is possible that someone took only one of the two pouches.

בְּתוֹךְ הַקֵּן וּמָצָא לִפְנֵי הַקֵּן — אֲסוּרִין. לֵימָא מְסַיַּיע לֵיהּ לְרַבִּי חֲנִינָא, דְּאָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא: רוֹב וְקָרוֹב — הַלֵּךְ אַחַר הָרוֹב!

§ The mishna taught that if one designated fledglings inside the nest and found them before the nest, they are prohibited. The Gemara comments: Let us say that this supports the opinion of Rabbi Ḥanina, as Rabbi Ḥanina said: In a case involving a majority and an item that is near, one follows the majority. Since doves from the outside world are more numerous than those that one designated, the assumption is that these fledglings are from the majority, and therefore they are prohibited.

אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: בְּדַף. רָבָא אָמַר: בִּשְׁנֵי קִנִּין זוֹ לְמַעְלָה מִזּוֹ עָסְקִינַן. וְלָא מִבַּעְיָא זִמֵּן בַּתַּחְתּוֹנָה וְלֹא זִמֵּן בָּעֶלְיוֹנָה, וּמָצָא בַּתַּחְתּוֹנָה וְלֹא מָצָא בָּעֶלְיוֹנָה — דַּאֲסִירָן, דְּאָמְרִינַן: הָנָךְ אֲזַלוּ לְעָלְמָא, וְהָנָךְ אִשְׁתְּרַבּוֹבֵי אִשְׁתַּרְבּוּב וּנְחוּת.

Abaye said, in refutation of this claim: Here we are dealing with a ledge affixed to the front of the nest, where all the doves gather. Therefore, the principle pertaining to a majority and an item that is near does not apply to this case. Rava said: Here we are dealing with two nests, one above the other, i.e., adjacent nests rather than any two nests. And it is not necessary to state that in the case of one who designated the fledglings in the lower nest and did not designate those in the upper one, and he found fledglings in the lower one and he did not find fledglings in the upper one, that the fledglings are all prohibited. The reason is that we say: These that were in the lower nest went to the outside world, while these still present have dragged themselves and come down.

אֶלָּא אֲפִילּוּ זִמֵּן בָּעֶלְיוֹנָה וְלֹא זִמֵּן בַּתַּחְתּוֹנָה, וּבָא וּמָצָא בָּעֶלְיוֹנָה וְלֹא מָצָא בַּתַּחְתּוֹנָה — הָנָךְ נָמֵי אֲסִירִי, דְּאָמְרִינַן: הָנָךְ אֲזַלוּ לְעָלְמָא, וְהָנָךְ סָרוֹכֵי סָרוּךְ וּסְלִיקוּ.

Rather, even if one designated fledglings in the upper nest and did not designate fledglings in the lower one, and he came and found fledglings in the upper one and did not find fledglings in the lower one, those in the upper nest are also prohibited, as we say: Those that he originally designated went to the outside world, and those in the lower nest have clutched and climbed. Therefore, there is cause for concern in both of these cases.

וְאִם אֵין שָׁם אֶלָּא הֵן — הֲרֵי אֵלּוּ מוּתָּרִין. הֵיכִי דָמֵי? אִילֵּימָא בִּמְפוֹרָחִין, אִיכָּא לְמֵימַר: הָנָךְ אֲזַלוּ לְעָלְמָא, וְהָנֵי אַחֲרִינֵי נִינְהוּ.

The mishna states that if there are no others there apart from them, they are permitted. The Gemara asks: What are the circumstances? If we say that the mishna is dealing with fledglings that are already able to fly, it is possible to say that those that he designated went to the outside world, and the ones that are present are other ones.

אֶלָּא בְּמִדַּדִּין. אִי דְּאִיכָּא קֵן בְּתוֹךְ חֲמִשִּׁים אַמָּה — אִדַּדּוֹיֵי אִדַּדּוֹ, וְאִי דְּלֵיכָּא קֵן בְּתוֹךְ חֲמִשִּׁים אַמָּה — פְּשִׁיטָא דְּמוּתָּרִין, דְּאָמַר מָר עוּקְבָא בַּר חָמָא: כׇּל הַמְדַדֶּה — אֵין מְדַדֶּה יוֹתֵר מֵחֲמִשִּׁים אַמָּה.

Rather, the mishna must be referring to fledglings that can only hop from one place to another. However, if it deals with a case where there is another dove nest within fifty cubits, the fledglings might have jumped and come from that nest; and if there is no nest within fifty cubits, it is obvious that they are permitted, for from where could they have come? As Mar Ukva bar Ḥama said: With regard to any creature that hops, it does not hop more than fifty cubits.

לְעוֹלָם דְּאִיכָּא קֵן בְּתוֹךְ חֲמִשִּׁים אַמָּה, וּכְגוֹן דְּקָיְימָא בְּקֶרֶן זָוִית. מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: אִדַּדּוֹיֵי אִדַּדּוֹ, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן כׇּל הֵיכָא דְּמִדַּדֵּה וַהֲדַר חָזֵי לְקִנֵּיהּ — מִדַּדֵּה, וְאִי לָא — לָא מִדַּדֵּה.

The Gemara answers: Actually, it is referring to a case where there is another nest within fifty cubits, and it deals with a situation where the additional nest is situated around a corner from the first nest, rather than in a straight line from it. Lest you say: The fledglings jumped from one nest to the other, the mishna therefore teaches us that anywhere that a fledgling hops and turns and sees its nest, it will continue to hop. But if it can no longer see its original nest, it will not hop any farther.

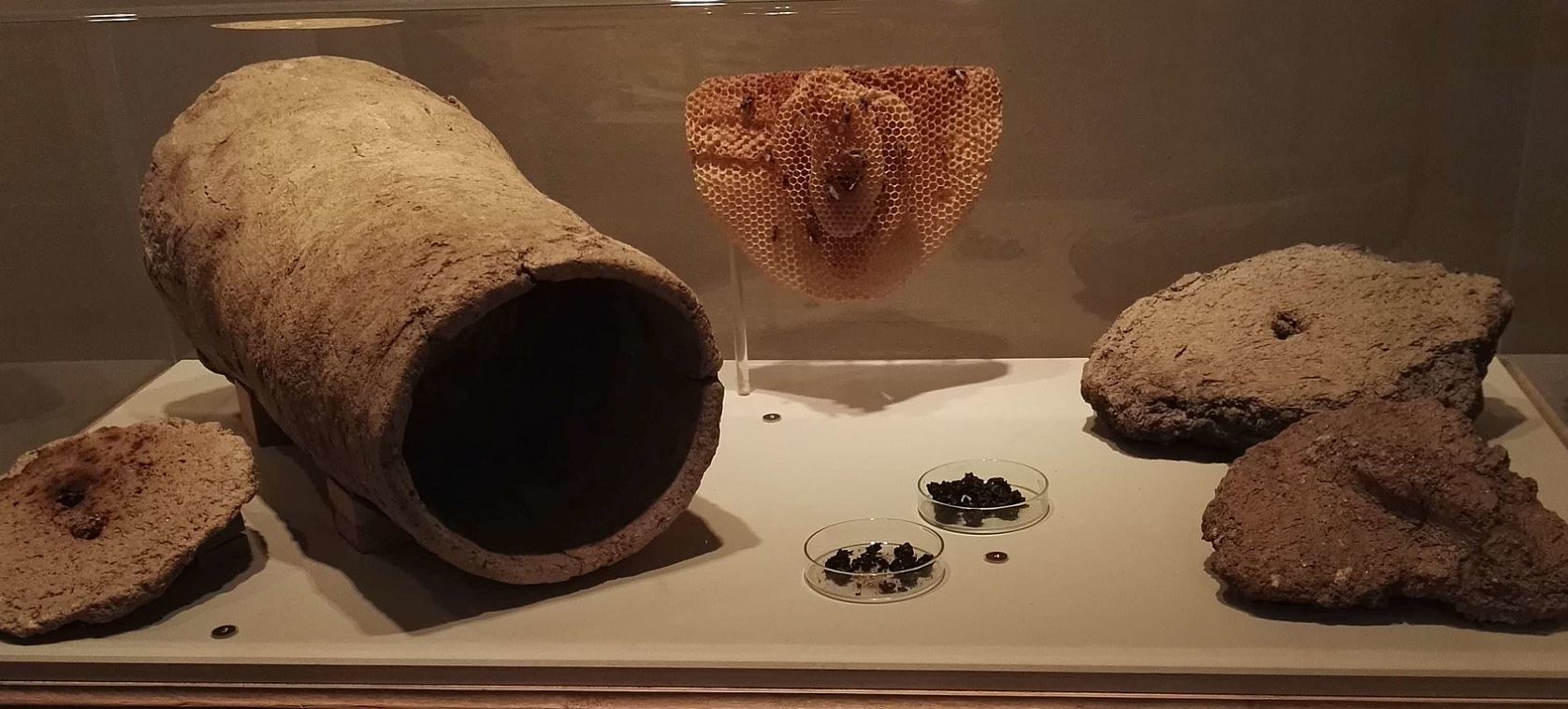

מַתְנִי׳ בֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים: אֵין נוֹטְלִים אֶת הָעֱלִי לְקַצֵּב עָלָיו בָּשָׂר, וּבֵית הִלֵּל מַתִּירִין. בֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים: אֵין נוֹתְנִין אֶת הָעוֹר לִפְנֵי הַדּוֹרְסָן. וְלֹא יַגְבִּיהֶנּוּ, אֶלָּא אִם כֵּן יֵשׁ עִמּוֹ כְּזַיִת בָּשָׂר, וּבֵית הִלֵּל מַתִּירִין.

MISHNA: Beit Shammai say: One may not take a large pestle from a mortar, which is normally used for crushing wheat in the preparation of porridge, for any other purpose on a Festival, e.g., to cut meat on it; and Beit Hillel permit it. Likewise, Beit Shammai say: One may not place an unprocessed hide before those who will tread on it, as this constitutes the prohibited labor of tanning on a Festival. And one may not lift the hide from its place, as it is considered muktze, unless there is an olive-bulk of meat on it, in which case it may be carried on account of its meat; and Beit Hillel permit it in both cases.

גְּמָ׳ תָּנָא: וְשָׁוִין שֶׁאִם קִצֵּב עָלָיו בָּשָׂר — שֶׁאָסוּר לְטַלְטְלוֹ.

GEMARA: The Sage taught in a baraita: And Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel agree that if one already cut the meat he needs for the Festival on the pestle, it is prohibited to move the pestle farther on the Festival. The reason is that the vessel is muktze as a utensil whose primary function is a prohibited use, and therefore it is permitted to handle it only when one requires it.

אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: מַחֲלוֹקֶת בֶּעֱלִי, אֲבָל בְּתָבְרָא גַּרְמֵי — דִּבְרֵי הַכֹּל מוּתָּר. פְּשִׁיטָא, עֱלִי תְּנַן!

Abaye said: This dispute applies specifically in the case of a pestle; however, in the case of a wooden anvil used for breaking bones, everyone agrees that it is permitted. The Gemara asks: This is obvious; we learned in the mishna: A pestle. Why would one think that an object not even mentioned in the mishna is prohibited?

מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: הוּא הַדִּין דַּאֲפִילּוּ תָּבְרָא גַּרְמֵי נָמֵי. וְהַאי דְּקָתָנֵי עֱלִי, לְהוֹדִיעֲךָ כֹּחָן דְּבֵית הִלֵּל, דַּאֲפִילּוּ דָּבָר שֶׁמְּלַאכְתּוֹ לֶאֱסוֹר נָמֵי שָׁרוּ — קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara answers: Abaye’s statement is necessary, lest you say: The same is true, i.e., Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel disagree, even with regard to a wooden anvil used for breaking bones; and that which the mishna specifically teaches: A pestle, is to convey the far-reaching nature of the opinion of Beit Hillel, that they permitted moving even an object whose primary function is for a prohibited use. Abaye therefore teaches us that Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel did not disagree with regard to a wooden anvil used for breaking bones.

אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי, אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: לֹא נִצְרְכָא אֶלָּא אֲפִילּוּ תָּבְרָא גַּרְמֵי חַדְתִּי, מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: מִמְּלֵךְ וְלָא תָּבַר עֲלַהּ — קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

Some say a different version of the previous discussion. Abaye said: It is necessary to say only: Even a new wooden anvil used for breaking bones is also permitted. Lest you say: Perhaps one will reconsider and not break bones on it, but rather set it aside for a different purpose, Abaye therefore teaches us that this is not a concern.

וּבֵית שַׁמַּאי לָא חָיְישִׁי לְאִמְּלוֹכֵי? וְהָתַנְיָא, בֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים: אֵין מוֹלִיכִין טַבָּח וְסַכִּין אֵצֶל בְּהֵמָה, וְלֹא בְּהֵמָה אֵצֶל טַבָּח וְסַכִּין. וּבֵית הִלֵּל אוֹמְרִים: מוֹלִיכִין זֶה אֵצֶל זֶה.

The Gemara asks: And is that so? Are Beit Shammai not concerned about the possibility that one might reconsider? But isn’t it taught (Tosefta, Beitza 1:13): Beit Shammai say: On a Festival, one may not lead a butcher with a knife in hand to an animal located far from him, so that he can slaughter it; nor may one lead an animal to a butcher with a knife, lest he reconsider, in which case he will have handled the knife unnecessarily, which is prohibited; and Beit Hillel say: One may lead them from one to the other, as they are not concerned about unnecessary use of the knife.

בֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים: אֵין מוֹלִיכִין תַּבְלִין וּמָדוֹךְ אֵצֶל מְדוֹכָה, וְלֹא מְדוֹכָה אֵצֶל תַּבְלִין וּמָדוֹךְ. וּבֵית הִלֵּל אוֹמְרִים: מוֹלִיכִין זֶה אֵצֶל זֶה!

By the same reasoning, Beit Shammai say: One may not bring spices or a pestle to a mortar, nor a mortar to spices and a pestle, as he might change his mind and will have handled these utensils on the Festival for no purpose. And Beit Hillel say: One may bring one to the other, as there is no concern that he may reconsider. This shows that Beit Shammai are, in general, concerned that one might reconsider, as they prohibit one to handle items for this reason.

הָכִי הַשְׁתָּא?! בִּשְׁלָמָא בְּהֵמָה אָתֵי לְאִמְּלוֹכֵי, דְּאָמַר: נִשְׁבֹּק הַאי בְּהֵמָה כְּחוּשָׁה, וּמַיְיתֵינָא בְּהֵמָה אַחֲרִיתִי דְּשַׁמִּינָה מִינַּהּ. קְדֵרָה נָמֵי אָתֵי לְאִימְּלוֹכֵי, דְּאָמַר: נִשְׁבֹּק הַאי קְדֵרָה דְּבָעֲיָא תַּבְלִין, וּמַיְיתֵינָא אַחֲרִיתִי דְּלָא בָּעֲיָא תַּבְלִין. הָכָא מַאי אִיכָּא לְמֵימַר? מִמְּלֵךְ וְלָא תָּבַר? כֵּיוָן דְּשַׁחְטַהּ — לִתְבִירָא קָיְימָא.

The Gemara refutes this: How can these cases be compared? Granted, in the case of an animal, one is liable to come to reconsider, as he might say: Let us leave aside this animal, as it is thin, and we will bring a different animal, fatter than it. With regard to a pot, too, one is liable to come to reconsider, as he might say: Let us leave aside this pot of cooked food, as it requires spices and would take great effort to prepare, and I will bring a different one that does not require spices and can be cooked as it is. However, here, with regard to a wooden anvil used for breaking bones, what is there to say? Will one reconsider and not break the bones? Since he has slaughtered an animal, it stands ready for its bones to be broken, as it cannot be eaten in any other way.

בֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים: אֵין נוֹתְנִין אֶת הָעוֹר. תָּנָא: וְשָׁוִין שֶׁמּוֹלְחִין עָלָיו בָּשָׂר לְצָלִי. אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: לֹא שָׁנוּ אֶלָּא לְצָלִי, אֲבָל לִקְדֵרָה — לֹא.

§ It was taught in the mishna that Beit Shammai say: One may not place an unprocessed hide before the one who will tread on it. The Sage taught (Tosefta, Beitza 1:13): And Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel agree that one may salt meat for roasting on this hide, and there is no concern that some of the salt will fall on the hide, which would be similar to tanning the hide by salting. Abaye said: They taught that one may salt meat only for roasting, in which case it is not salted a great deal. However, in the case of meat for a pot, i.e., for cooking, the Sages did not say that one may salt it on the hide, as meat must be well-salted on all sides before cooking, and a large amount of salt will inevitably spill onto the hide.

פְּשִׁיטָא — לְצָלִי תְּנַן! הָא קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן דַּאֲפִילּוּ לְצָלִי, כְּעֵין קְדֵרָה — אָסוּר.

The Gemara asks: It is obvious the one may not salt meat for cooking in a pot, as we explicitly learned in the Tosefta just cited: For roasting, and not for cooking. The Gemara answers: This comes to teach us that even the permission to salt meat for roasting applies only if one does so in the usual manner. However, if one salts it in a manner of meat salted to be cooked in a pot, which requires more salt than is necessary for roasting, it is prohibited.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: אֵין מוֹלְחִין אֶת הַחֲלָבִים וְאֵין מְהַפְּכִין בָּהֶן. מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ אֲמַרוּ: שׁוֹטְחָן בָּרוּחַ עַל גַּבֵּי יְתֵדוֹת.

The Sages taught: On a Festival, one may not salt the fats of an animal, which is done so that they will not decompose and emit a foul odor. This is true even if the animal was slaughtered on the Festival. And one may not turn them over. The fats are unfit for use on the Festival, and therefore they are muktze. They said in the name of Rabbi Yehoshua: One may spread the fats out in the wind on pegs to prevent them from decaying.

אָמַר רַב מַתְנָה: הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ. אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי, אָמַר רַב מַתְנָה: אֵין הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ. בִּשְׁלָמָא לְמַאן דְּאָמַר הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ — אִצְטְרִיךְ, סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ אָמֵינָא יָחִיד וְרַבִּים הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּים, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן הֲלָכָה כְּיָחִיד.

Rav Mattana said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehoshua. Some say that Rav Mattana said: The halakha is not in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehoshua. The Gemara asks: Granted, according to the one who said that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehoshua, this statement is necessary. Otherwise, it might enter your mind to say that since this is a dispute between an individual and the many, one should apply the principal that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of the many. Rav Mattana therefore teaches us that, in this case, the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of the individual.

אֶלָּא לְמַאן דְּאָמַר אֵין הֲלָכָה — פְּשִׁיטָא, יָחִיד וְרַבִּים הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּים! מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: מִסְתַּבַּר טַעְמֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ דְּאִי לָא שָׁרֵית לֵיהּ מִמְּנַע וְלָא שָׁחֵיט, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

However, according to the one who said that the halakha is not in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehoshua, this is obvious. In a case involving an individual and the many, the halakha is in accordance with the many. The Gemara answers: This ruling is nevertheless necessary, lest you say: Rabbi Yehoshua’s opinion is more reasonable, for if you do not permit him to air out the fats, he will refrain and not slaughter an animal at all. Rav Mattana therefore teaches us that this factor is not taken into consideration.

וּמַאי שְׁנָא מֵעוֹר לִפְנֵי הַדּוֹרְסָן?

The Gemara asks: And in what way is this case different from placing a hide before those who will tread on it, which Beit Hillel, whose ruling is accepted as halakha, permit for the very reason that, if one is not allowed to do so, he will refrain from slaughtering animals?

הָתָם לָא מוֹכְחָא מִלְּתָא, מִשּׁוּם דַּחֲזֵי לְמִזְגֵּא עֲלֵיהּ. הָכָא אָתֵי לְמֵימַר: מַאי טַעְמָא שָׁרוּ לִי רַבָּנַן — כִּי הֵיכִי דְּלָא לִסְרַח. מָה לִי לְמִשְׁטְחִינְהוּ, מָה לִי לְמִמְלְחִינְהוּ.

The Gemara answers: There, in the case of spreading out the hide, the matter is not so evident that it is spread out for tanning because in its current state, it is fit to recline on, and therefore it can be said that one placed it for this purpose. However, here, with regard to fats, he himself might come to say: What is the reason that the Sages permitted it to me? So that it will not emit a foul odor. If so, what is the difference to me if I spread them out, and what is the difference to me if I salt them? This reasoning will lead one to salt hides, which is a prohibited labor.

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: מוֹלֵחַ אָדָם כַּמָּה חֲתִיכוֹת בָּשָׂר בְּבַת אַחַת, אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁאֵינוֹ צָרִיךְ אֶלָּא לַחֲתִיכָה אַחַת. רַב אַדָּא בַּר אַהֲבָה מַעֲרִים וּמָלַח גַּרְמָא גַּרְמָא.

Rav Yehuda said that Shmuel said: A person may salt on a Festival several pieces of meat at one time, although he requires only one piece, as it is all one act of salting. Rav Adda bar Ahava would employ artifice and salt bone by bone. After salting one bone, he would say: I prefer this one instead, and would thereby salt all the meat in his possession.

מַתְנִי׳ בֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים: אֵין מְסַלְּקִין אֶת הַתְּרִיסִין בְּיוֹם טוֹב, וּבֵית הִלֵּל מַתִּירִין אַף לְהַחְזִיר.

MISHNA: Beit Shammai say: One may not remove the shutters [terisin] of a store on a Festival, due to the prohibition against building and demolishing. And Beit Hillel permit one not only to open the shutters, but even to replace them.

גְּמָ׳ מַאי תְּרִיסִין? אָמַר עוּלָּא: תְּרִיסֵי חֲנוּיוֹת.

GEMARA: The Gemara asks: What are these shutters? Ulla said: This is referring to shutters of shops. The marketplace shops or stalls were large crates or wagons, not buildings. They were closed at night with shutters. The shopkeepers would open the shutters on the Festival so that people who did not manage to finish all of their Festival preparations before the Festival could take the articles they required and settle accounts with the storekeeper later. Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel disputed whether the shutters may be opened and closed on the Festival itself.

וְאָמַר עוּלָּא: שְׁלֹשָׁה דְּבָרִים הִתִּירוּ סוֹפָן מִשּׁוּם תְּחִלָּתָן, וְאֵלּוּ הֵן: עוֹר לִפְנֵי הַדּוֹרְסָן, וּתְרִיסֵי חֲנוּיוֹת,

And Ulla said: With regard to three matters, the Sages permitted an action whose result is undesirable in order to encourage a desirable initial action. And these are the three matters: First, they permitted spreading out the hide of an animal slaughtered on a Festival before those who will tread on it, a stage in its tanning. This was permitted because the Sages wish to encourage slaughtering the animal to enable celebration on the Festival. And second, the Sages permitted the replacement of shutters of shops on a Festival, so that storeowners could supply the Festival requirements for those in need.

וַחֲזָרַת רְטִיָּה בַּמִּקְדָּשׁ.

And the third permitted action is the replacement of a bandage in the Temple. If a priest had an injury on his hand, he would have to remove the bandage while performing the Temple service, as it is prohibited for any item to interpose between his hand and whatever he must handle as part of the rite. After concluding his Temple service, he was allowed to replace the bandage on Shabbat, despite the fact that this is ordinarily prohibited, so as not to discourage him from engaging in Temple service.

וְרַחֲבָא אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: אַף הַפּוֹתֵחַ חָבִיתוֹ, וּמַתְחִיל בְּעִיסָּתוֹ עַל גַּב הָרֶגֶל —

And Raḥava said that Rabbi Yehuda said: There is also one other matter, i.e., another instance where the Sages permitted an action whose result was undesirable in order to encourage a desirable initial action. This concerns a ḥaver, a member of a group that is meticulous with regard to the halakhot of ritual impurity, who opens his barrel of wine or prepares and begins to sell his dough to pilgrims for the sake of the Festival.

וְאַלִּיבָּא דְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה דְּאָמַר יִגְמוֹר.

And this is according to the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda, who said: He may finish selling all the bread made from that dough and all the wine in the barrel. Wine or dough sold to the general public is usually classified as ritually impure, as it might have been touched by an am ha’aretz, one who is not careful with regard to the halakhot of ritual impurity. During a Festival, however, the Sages decreed that all wine and dough sold in Jerusalem is ritually pure, so as not to embarrass ignorant people, and they may therefore be bought even by a ḥaver. Rabbi Yehuda adds that even if a large quantity of wine or dough remains after the Festival, it retains its status as ritually pure and one may continue to sell it to a ḥaver. This is a case of permitting an action whose result is undesirable for the sake of an initial action, in that the Sages maintained the wine and dough’s status as ritually pure after the Festival in order to encourage people to sell wine and dough on the Festival.

עוֹר לִפְנֵי הַדּוֹרְסָן, תְּנֵינָא! מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא טַעְמַיְיהוּ דְּבֵית הִלֵּל מִשּׁוּם דַּחֲזֵי לְמִזְגֵּא עֲלַיְיהוּ, וַאֲפִילּוּ מֵעֶרֶב יוֹם טוֹב נָמֵי — קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן הִתִּירוּ סוֹפָן מִשּׁוּם תְּחִלָּתָן: דְּיוֹם טוֹב — אִין, דְּעֶרֶב יוֹם טוֹב — לָא.

With regard to Ulla’s statement, the Gemara asks: We already learned the halakha that one may spread out an animal’s hide before those who will tread on it. Why did Ulla find it necessary to restate an explicit teaching of a mishna? The Gemara explains: Lest you say that the reason of Beit Hillel is because the hide is fit for reclining on it, and therefore even if the animal was slaughtered on the eve of the Festival, it would also be permitted to spread out its hide on the Festival. Ulla therefore teaches us that the reason for the leniency is that the Sages permitted an action whose result was undesirable in order to encourage a desirable initial action. Consequently, in the case of an animal slaughtered on a Festival, yes, this halakha applies; but with regard to one that was slaughtered on the eve of a Festival, no, one may not spread out its hide.

תְּרִיסִי חֲנוּיוֹת נָמֵי תְּנֵינָא [וּבֵית הִלֵּל מַתִּירִין אַף לְהַחְזִיר]! מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא טַעְמַיְיהוּ דְּבֵית הִלֵּל מִשּׁוּם דְּאֵין בִּנְיָן בְּכֵלִים וְאֵין סְתִירָה בְּכֵלִים, וַאֲפִילּוּ דְּבָתִּים נָמֵי — קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן הִתִּירוּ סוֹפָן מִשּׁוּם תְּחִלָּתָן: דַּחֲנוּיוֹת — אִין, דְּבָתִּים — לָא.

The Gemara further asks: We already learned the halakha of the shutters of shops as well, as the mishna states that Beit Hillel permit one even to replace them. The Gemara explains: This, too, is necessary. Lest you say: Beit Hillel’s reason for being lenient is that there is no prohibition of building with regard to vessels and no prohibition of dismantling with regard to vessels. Since these shops are not attached to the ground, they are vessels rather than houses, and it is therefore permitted to replace their shutters; and as a result, the dismantlement and replacement of shutters of large vessels, even of those found in houses, should also be permitted. To counter this logic, Ulla therefore teaches us that the reason the Sages allowed the replacement of shutters of shops on a Festival is because they permitted an action whose result is undesirable in order to encourage a desirable initial action. Consequently, in the case of the shutters of shops, yes, they permitted their replacement; in the case of those of houses, no, they did not allow it.

חֲזָרַת רְטִיָּה בַּמִּקְדָּשׁ נָמֵי תְּנֵינָא: מַחְזִירִין רְטִיָּה בַּמִּקְדָּשׁ אֲבָל לֹא בַּמְּדִינָה! מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא טַעְמָא מַאי — מִשּׁוּם דְּאֵין שְׁבוּת בַּמִּקְדָּשׁ, אֲפִילּוּ כֹּהֵן דְּלָאו בַּר עֲבוֹדָה הוּא, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן הִתִּירוּ סוֹפָן מִשּׁוּם תְּחִלָּתָן: דְּבַר עֲבוֹדָה — אִין, דְּלָאו בַּר עֲבוֹדָה — לָא.

The Gemara further asks: We already learned the halakha of the replacement of a bandage in the Temple as well: One may replace a bandage in the Temple but not in the rest of the country. The Gemara explains that this halakha is necessary. Lest you say: What is the reason that a bandage may be replaced? It is because rabbinic decrees prohibiting labor do not apply in the Temple. Since the prohibition against applying a bandage is by rabbinic law, this leniency should apply to all who are in the Temple, even to a priest who is not a candidate to perform the Temple service. Ulla teaches us that this is not the case; rather, it is an instance where the Sages permitted a result for the sake of an initial action: If one is a candidate for service, yes, he may replace his bandage; if one is not a candidate for service, no, he may not replace his bandage.

פּוֹתֵחַ אֶת חָבִיתוֹ נָמֵי תְּנֵינָא: הַפּוֹתֵחַ אֶת חָבִיתוֹ, וּמַתְחִיל בְּעִיסָּתוֹ עַל גַּב הָרֶגֶל, רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: יִגְמוֹר, וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: לֹא יִגְמוֹר.

The Gemara asks a similar question with regard to Raḥava’s addition: We already learned the halakha of one who opens his barrel of wine, as well: In the case of one who opens his barrel to sell its wine, and similarly in the case of one who begins selling his dough for the sake of the Festival, the substance is ritually pure. If some is left over, the tanna’im disputed whether it retains its presumed status as ritually pure after the Festival and one may continue to sell it to a ḥaver. Rabbi Yehuda says: He may finish selling the wine or dough, and the Rabbis say: He may not finish. What is added by including it in the list of matters where a result is permitted for the sake of an initial action?

מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא טוּמְאַת עַם הָאָרֶץ בָּרֶגֶל כְּטׇהֳרָה שַׁוְּיוּהָ רַבָּנַן, וְאַף עַל גַּב דְּלָא הִתְחִיל נָמֵי, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן הִתִּירוּ סוֹפָן מִשּׁוּם תְּחִלָּתָן: הִתְחִיל — אִין, לֹא הִתְחִיל — לָא.

The Gemara explains: Raḥava’s statement is necessary. Lest you say: It is permitted to finish selling the wine or dough because the Sages rendered the ritual impurity of an am ha’aretz on a Festival as ritually pure, and although one did not begin to sell this wine or dough on the Festival but at an earlier stage, he should likewise be permitted to finish, as items do not contract ritual impurity on a Festival. To counter this logic, Raḥava therefore teaches us: In this case, too, the Sages permitted an action whose result is undesirable in order to encourage a desirable initial action. If one had begun, yes, he may finish selling; if one had not begun, no, he may not do so.

וְעוּלָּא מַאי טַעְמָא לָא אָמַר הָא? בִּפְלוּגְתָּא לָא קָא מַיְירֵי. הָנָךְ נָמֵי פְּלוּגְתָּא נִינְהוּ! בֵּית שַׁמַּאי בִּמְקוֹם בֵּית הִלֵּל אֵינָהּ מִשְׁנָה.

The Gemara asks: And Ulla, what is the reason that he did he not state this halakha alongside the other cases he listed? The Gemara answers: He is not dealing with a case that is a matter of dispute. He listed only cases where the ruling is unanimous. The Gemara challenges this: These other three matters are also subject to dispute, as they all involve a disagreement between Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel. The Gemara answers: When Beit Shammai express an opinion where Beit Hillel disagree, Beit Shammai’s opinion is not considered a legitimate opinion in the Mishna, and it is completely disregarded. Since everyone knows that Beit Shammai’s opinion is entirely rejected by halakha, it is not taken into consideration. Therefore, those cases are not viewed as disputes at all.

מַתְנִיתִין דְּלָא כִי הַאי תַּנָּא דְּתַנְיָא, אָמַר רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן אֶלְעָזָר: מוֹדִים בֵּית שַׁמַּאי וּבֵית הִלֵּל שֶׁמְּסַלְּקִין אֶת הַתְּרִיסִין בְּיוֹם טוֹב, לֹא נֶחְלְקוּ אֶלָּא לְהַחֲזִיר. שֶׁבֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים: אֵין מַחְזִירִין, וּבֵית הִלֵּל אוֹמְרִים: אַף מַחְזִירִין. בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים — בְּשֶׁיֵּשׁ לָהֶן צִיר, אֲבָל אֵין לָהֶן צִיר — דִּבְרֵי הַכֹּל מוּתָּר.

§ The Gemara comments: The mishna is not in accordance with the opinion of this tanna, as it is taught: Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar said: Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel agree that one may remove shutters on a Festival. They disagree only as to whether it is permitted to replace them, as well, as Beit Shammai say: One may not replace them, and Beit Hillel say: One may even replace them. And in what case is this statement said? When these shutters have a hinge that can be inserted into a slot in the side of the vessel. However, if they do not have a hinge, everyone agrees that it is permitted, as this is merely replacement of a board, and it is not similar to building.

וְהָתַנְיָא: בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים — בְּשֶׁאֵין לָהֶן צִיר, אֲבָל יֵשׁ לָהֶן צִיר — דִּבְרֵי הַכֹּל אָסוּר! אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: בְּשֶׁיֵּשׁ לָהֶן צִיר מִן הַצַּד — דִּבְרֵי הַכֹּל אָסוּר. אֵין לָהֶן צִיר כׇּל עִיקָּר — דִּבְרֵי הַכֹּל מוּתָּר. כִּי פְּלִיגִי בְּשֶׁיֵּשׁ לָהֶן צִיר בָּאֶמְצַע.

The Gemara challenges this claim: But isn’t it taught in a baraita: In what case is this statement said? What is the situation in which Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel disagree? They disagree when the shutters do not have a hinge; however, if they have a hinge, everyone agrees that it is prohibited. Abaye said that the two sources can be reconciled: When they have a hinge on the side, everyone agrees that it is prohibited, as the placement of a hinge in the side is a complicated endeavor that resembles building. If they have no hinge at all, everyone agrees that it is permitted, as it is considered merely the replacement of a board. When they disagree, it is with regard to a case where they have a hinge in the middle rather than on the side.