Beitzah 30

בַּעֲרֵמַת הַתֶּבֶן, אֲבָל לֹא בָּעֵצִים שֶׁבַּמּוּקְצֶה.

from the pile of straw, although he did not designate the pile for this purpose the day before; but one may not begin to take from the wood in the wood storage, a small yard behind the house where people store various items that they do not intend to use in the near future.

גְּמָ׳ תָּנָא: אִם אִי אֶפְשָׁר לְשַׁנּוֹת — מוּתָּר.

GEMARA: A tanna taught in a baraita: If it is impossible to modify the manner in which one carries a vessel, whether due to the vessel or due to time constraints, it is permitted to act in the typical weekday manner.

אַתְקִין רָבָא בְּמָחוֹזָא: דְּדָרוּ בְּדוּחְקָא — לִדְרוֹ בְּרִגְלָא. דְּדָרוּ בְּרִגְלָא — לִדְרוֹ בְּאַגְרָא. דְּדָרוּ בְּאַגְרָא — לִדְרוֹ בְּאַכְפָּא. דְּדָרוּ בְּאַכְפָּא — נִפְרוֹס סוּדָרָא עִלָּוֵיהּ, וְאִם לָא אֶפְשָׁר — שְׁרֵי. דְּאָמַר מָר: אִם אִי אֶפְשָׁר לְשַׁנּוֹת — מוּתָּר.

The Gemara relates that Rava instituted the following in his city, Meḥoza: One who usually carries his burden with difficulty on a weekday should modify his habit on a Festival and carry it on a pitchfork. One who usually carries it on a pitchfork should carry it on a carrying pole held by two people on their shoulders. One who carries it on a carrying pole held by two people on their shoulders should carry it on a carrying pole in his hands, although he is not thereby making it easier for himself. One who carries burdens on a carrying pole in his hands should spread a scarf [sudara] over it. And if it is not possible to make these modifications due to time constraints, it is permitted to proceed in the usual manner, as the Master said above: If it is impossible to modify, it is permitted.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב חָנָן בַּר רָבָא לְרַב אָשֵׁי: אֲמוּר רַבָּנַן כַּמָּה דְּאֶפְשָׁר לְשַׁנּוֹיֵי מְשַׁנֵּינַן בְּיוֹמָא טָבָא. וְהָא הָנֵי נְשֵׁי דְּקָא מָלְיָין חַצְבַיְיהוּ מַיָּא בְּיוֹמָא טָבָא, וְלָא קָא מְשַׁנְּיָין, וְלָא אָמְרִינַן לְהוּ וְלָא מִידֵּי!

Rav Ḥanan bar Rava said to Rav Ashi: The Sages said: As much as it is possible to modify the weekday manner, one should modify on a Festival. A question was asked of Rav Ashi: But don’t those women fill their jugs with water on a Festival without modifying, and we say nothing to them by way of protest; why do we not instruct them to alter their usual manner?

אֲמַר לֵיהּ: מִשּׁוּם דְּלָא אֶפְשָׁר. הֵיכָא לֶיעְבַּד? דְּמָלְיָא בְּחַצְבָּא רַבָּה תִּמְלֵי בְּחַצְבָּא זוּטָא — קָא מַפְּשָׁא בְּהִלּוּכָא.

He said to him: It is because it is not possible for them to fill their jugs any other way. How should they act? She who is accustomed to filling a large jug, should she instead fill a small jug? Won’t this mean that she increases her walking, since she has to make more than one trip to bring home more than one jug, and she will thereby perform unnecessary labor on the Festival?

דְּמָלְיָא בְּחַצְבָּא זוּטָא תִּמְלֵי בְּחַצְבָּא רַבָּה — קָא מַפְּשָׁא בְּמַשּׂוֹי. תְּכַסְּיֵיהּ בְּנִכְתְּמָא — זִמְנִין דְּנָפֵיל וְאָתֵי לְאֵתוֹיֵי. תִּקְטְרֵיהּ — זִמְנִין דְּמִפְּסִיק וְאָתֵי לְמִקְטְרֵיהּ. תִּפְרוֹס סוּדָרָא עִלָּוֵיהּ — זִמְנִין דְּמִטְּמִישׁ בְּמַיָּא וְאָתֵי לִידֵי סְחִיטָה. הִלְכָּךְ לָא אֶפְשָׁר.

If one were to suggest the opposite, that one who fills a small jug should fill a large jug, won’t this mean that she increases her load? Furthermore, if one were to suggest that she should cover the jug with a wooden cover, sometimes it falls and she might come to bring it by hand, in the manner of a burden. Should she tie the cover to the jug, the rope might occasionally break, and she might come to tie it, a prohibited labor. Finally, should she spread a scarf over it, it occasionally falls off and becomes soaked in water, and she might come to transgress the prohibition against squeezing. Therefore, it is not possible to make a modification, and those women may act in the regular manner.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא בַּר רַב חָנִין לְאַבָּיֵי, תְּנַן: אֵין מְטַפְּחִין וְאֵין מְסַפְּקִין וְאֵין מְרַקְּדִין, וְהָאִידָּנָא דְּקָא חָזֵינַן דְּעָבְדָן הָכִי, וְלָא אָמְרִינַן לְהוּ וְלָא מִידֵּי?

Rava bar Rav Ḥanin said to Abaye: We learned in a mishna: The Rabbis decreed that one may not clap, nor strike a hand on his thigh, nor dance on a Festival, lest he come to repair musical instruments. But nowadays we see that women do so, and yet we do not say anything to them.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ: וּלְטַעְמָךְ הָא דְּאָמַר (רָבָא): לָא לֵיתֵיב אִינִישׁ אַפּוּמָּא דְלִחְיָא, דִּלְמָא מִגַּנְדַּר לֵיהּ חֵפֶץ וְאָתֵי לְאֵתוֹיֵי (אַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת בִּרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים), וְהָא הָנֵי נְשֵׁי דְּשָׁקְלָן חַצְבַיְיהוּ, וְאָזְלָן וְיָתְבָן אַפּוּמָּא דִמְבוֹאָה, וְלָא אָמְרִינַן לְהוּ וְלָא מִידֵּי!

He said to him: And according to your reasoning, how do you explain that which Rava said: A person should not sit at the entrance to an alleyway, next to the side post that has been placed at the edge of an alleyway in order for it to be considered a private domain, as perhaps an object will roll away from him and he will come to carry it four cubits in the public domain, thereby transgressing a biblical prohibition? But don’t these women take their jugs, and go, and sit at the entrance to an alleyway, and we do not say anything to them?

אֶלָּא: הַנַּח לָהֶם לְיִשְׂרָאֵל, מוּטָב שֶׁיִּהְיוּ שׁוֹגְגִין וְאַל יִהְיוּ מְזִידִין. הָכָא נָמֵי: הַנַּח לָהֶם לְיִשְׂרָאֵל, מוּטָב שֶׁיִּהְיוּ שׁוֹגְגִין וְאַל יִהְיוּ מְזִידִין.

Rather, the accepted principle is: Leave the Jews alone; it is better that they be unwitting sinners and not be intentional sinners. If people engage in a certain behavior that cannot be corrected, it is better not to reprove them, as they are likely to continue regardless of the reproof, and then they will be sinning intentionally. It is therefore preferable for them to be unaware that they are violating a prohibition and remain merely unwitting sinners. Here, too, with regard to clapping and dancing, leave the Jews alone; it is better that they be unwitting sinners and not be intentional sinners.

וְהָנֵי מִילֵּי בִּדְרַבָּנַן, אֲבָל בִּדְאוֹרָיְיתָא — לָא. וְלָא הִיא, לָא שְׁנָא בִּדְאוֹרָיְיתָא וְלָא שְׁנָא בִּדְרַבָּנַן, לָא אָמְרִינַן לְהוּ וְלָא מִידֵּי, דְּהָא תּוֹסֶפֶת יוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים דְּאוֹרָיְיתָא הוּא, וְאָכְלִי וְשָׁתוּ עַד שֶׁחָשְׁכָה, וְלָא אָמְרִינַן לְהוּ וְלָא מִידֵּי.

The Gemara comments: There were those who understood that this principle applies only to rabbinic prohibitions but not to Torah prohibitions, with regard to which the transgressors must be reprimanded. However, this is not so; it is no different whether the prohibition is by Torah law or whether it is by rabbinic law, we do not say anything to them. For example, on the eve of Yom Kippur, there is an obligation that one begin the fast while it is still day, before sunset, as the extension of Yom Kippur. During this time, one must observe all the halakhot. This mitzva of extending Yom Kippur is by Torah law, and yet people eat and drink until darkness falls but we do not say anything to them, as we know they will pay no attention.

וּמַתְחִילִין בַּעֲרֵמַת הַתֶּבֶן. אָמַר רַב כָּהֲנָא: זֹאת אוֹמֶרֶת, מַתְחִילִין בָּאוֹצָר תְּחִלָּה. מַנִּי — רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן הִיא, דְּלֵית לֵיהּ מוּקְצֶה.

It is taught in the mishna: And one may begin taking straw from the pile of straw. Rav Kahana said: That is to say that one may begin removing items from a storeroom on a Festival ab initio. Although the items in this storeroom are designated for other purposes, it is not assumed that one put them out of his mind. If so, in accordance with whose opinion is this mishna? It is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Shimon, who is not of the opinion that there is a prohibition of set-aside [muktze]. According to him, on Shabbat and Festivals it is not prohibited to handle items that one has removed from his mind.

אֵימָא סֵיפָא: אֲבָל לֹא בָּעֵצִים שֶׁבַּמּוּקְצֶה. אֲתָאן לְרַבִּי יְהוּדָה, דְּאִית לֵיהּ מוּקְצֶה! הָכָא בְּאַרְזֵי וְאַשּׁוּחֵי עָסְקִינַן, דְּמוּקְצֶה מֵחֲמַת חֶסְרוֹן כִּיס, וַאֲפִילּוּ רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן מוֹדֶה.

The Gemara challenges: Say the latter clause of the same mishna as follows: But not wood in the wood storage. If so, we have come to the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda, who is of the opinion that there is a prohibition of muktze. The Gemara answers: Here, we are dealing with wood of cedars and firs, which are expensive and used only in the construction of important buildings, not for kindling; the wood storage is therefore considered muktze due to potential monetary loss. With regard to an item that one removes from his mind due to the financial loss he might suffer were he to use it, but not due to any prohibition involved, even Rabbi Shimon concedes that it may not be handled due to the prohibition of muktze.

אִיכָּא דְּמַתְנֵי לַהּ אַסֵּיפָא: אֲבָל לֹא בָּעֵצִים שֶׁבַּמּוּקְצֶה. אָמַר רַב כָּהֲנָא: זֹאת אוֹמֶרֶת, אֵין מַתְחִילִין בָּאוֹצָר תְּחִלָּה. מַנִּי — רַבִּי יְהוּדָה הִיא, דְּאִית לֵיהּ מוּקְצֶה. אֵימָא רֵישָׁא: מַתְחִילִין בַּעֲרֵמַת הַתֶּבֶן, אֲתָאן לְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן דְּלֵית לֵיהּ מוּקְצֶה! הָתָם בְּתִבְנָא סַרְיָא.

There are those who taught the statement of Rav Kahana as referring to the latter clause of the mishna, as follows: But not wood from the wood storage area. Rav Kahana said: That is to say that one may not begin removing items from a storeroom ab initio. If so, in accordance with whose opinion is the mishna? It is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda, who maintains that there is a prohibition of muktze. The Gemara challenges: Say the first clause of the mishna, which states that one may begin taking from the pile of straw. If so, we have come to the opinion of Rabbi Shimon, who is not of the opinion that there is a prohibition of muktze. The Gemara answers: There, in the first clause of the mishna, it is dealing with straw that has rotted and become rancid. Since it is no longer fit as animal fodder, even Rabbi Yehuda concedes that it will be used for kindling and is not muktze.

תִּבְנָא סַרְיָא, הָא חֲזֵי לְטִינָא! דְּאִית בֵּיהּ קוֹצִים.

The Gemara asks: Isn’t rancid straw fit for clay in the making of bricks; why can one assume that it will be used as fuel? The Gemara answers: The mishna is referring to straw that has thorns, which cannot be kneaded into clay. It will certainly be used only for kindling.

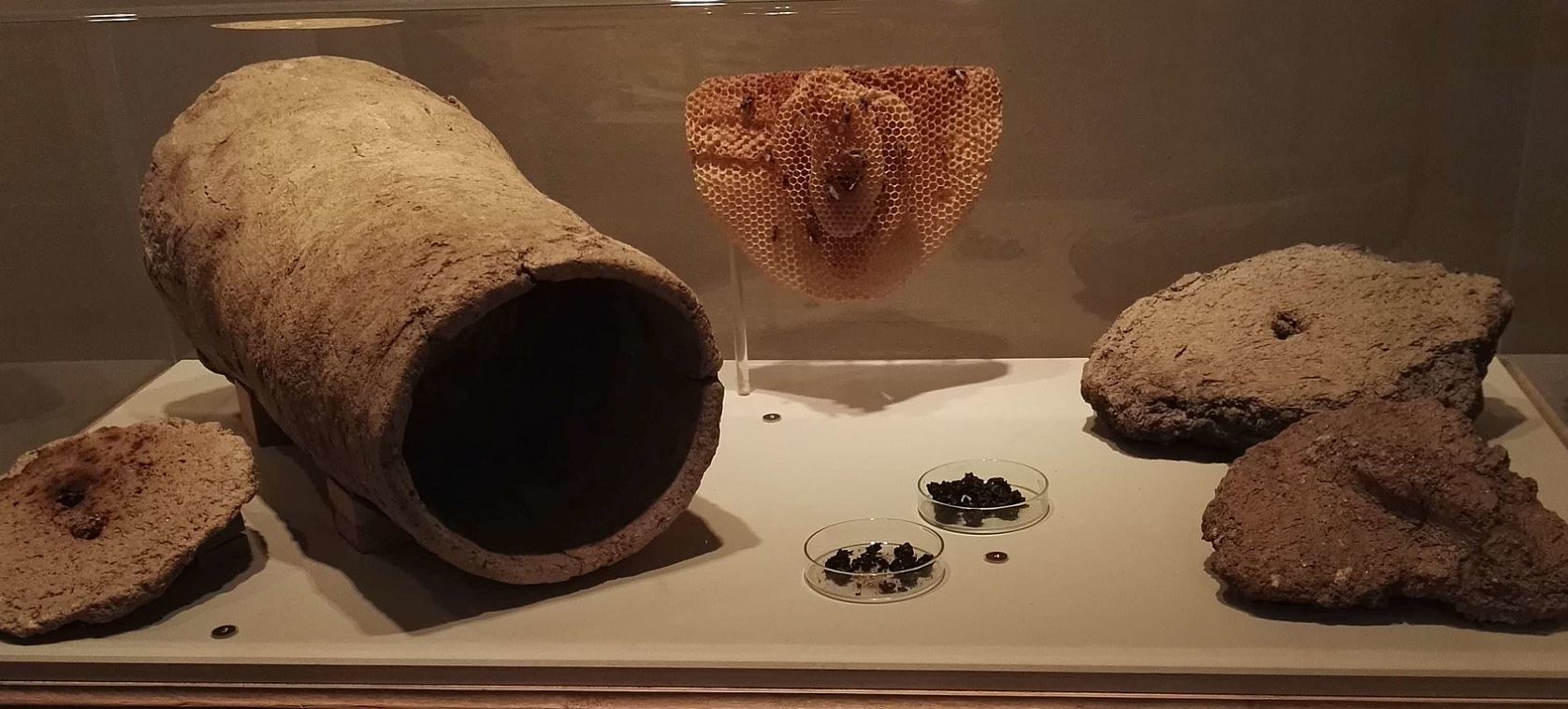

מַתְנִי׳ אֵין נוֹטְלִין עֵצִים מִן הַסּוּכָּה, אֶלָּא מִן הַסָּמוּךְ לָהּ.

MISHNA: One may not take wood from a sukka on any Festival, not only on the festival of Sukkot, because this is considered dismantling, but one may take from near it.

גְּמָ׳ מַאי שְׁנָא מִן הַסּוּכָּה דְּלָא — דְּקָא סָתַר אֻהְלָא, מִן הַסָּמוּךְ לָהּ נָמֵי — קָא סָתַר אֻהְלָא?

GEMARA: The Gemara poses a question with regard to the mishna: In what way is this case different? Why did the mishna teach that from the sukka itself one may not remove wood? It is because one thereby dismantles a tent, which is a prohibited labor. But if so, if one takes wood from near it, too, doesn’t he thereby dismantle a tent? Why, then, does the mishna permit him to do so?

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: מַאי סָמוּךְ — סָמוּךְ לַדְּפָנוֹת. רַב מְנַשְּׁיָא אָמַר: אֲפִילּוּ תֵּימָא בְּשֶׁאֵין סָמוּךְ לַדְּפָנוֹת, כִּי תַּנְיָא הָהִיא — בְּאִסּוּרְיָיתָא.

Rav Yehuda said that Shmuel said: What is the meaning of: Near it? It means near the walls. Wood placed near the walls may be removed because it is not part of the sukka itself; the walls themselves may not be removed. Rav Menashya said: Even if you say that it is referring to a case where the wood is not near the walls but is part of the roof of the sukka itself, when that baraita was taught, it was with regard to bundles of reeds that are not considered part of the roof of the sukka, as they have not been untied. Therefore, one may remove them.

תַּנְיָא רַבִּי חִיָּיא בַּר יוֹסֵף קַמֵּיהּ דְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: אֵין נוֹטְלִין עֵצִים מִן הַסּוּכָּה אֶלָּא מִן הַסָּמוּךְ לָהּ, וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן מַתִּיר. וְשָׁוִין בְּסוּכַּת הַחַג בֶּחָג — שֶׁאֲסוּרָה. וְאִם הִתְנָה עָלֶיהָ — הַכֹּל לְפִי תְנָאוֹ.

Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Yosef taught the following baraita before Rabbi Yoḥanan: One may not take wood from the sukka itself but only from the nearby wood. And Rabbi Shimon permits one to take wood from the sukka as well. And all agree, even Rabbi Shimon, that with regard to the sukka that was built for the festival of Sukkot, during the Festival it is prohibited to remove wood from it. But if at the outset one stipulated a condition with regard to it allowing him to use it for other purposes, it is all according to his stipulation.

וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן מַתִּיר? וְהָא קָא סָתַר אֻהְלָא! אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק: הָכָא בְּסוּכָּה נוֹפֶלֶת עָסְקִינַן, וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן לְטַעְמֵיהּ, דְּלֵית לֵיהּ מוּקְצֶה. דְּתַנְיָא: מוֹתַר הַשֶּׁמֶן שֶׁבַּנֵּר וְשֶׁבַּקְּעָרָה — אָסוּר. וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן מַתִּיר.

The Gemara questions this baraita: And does Rabbi Shimon permit one to take wood from the sukka itself? But isn’t one dismantling a tent, which is a prohibited labor? The Gemara answers that Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak said: Here, we are dealing with a sukka that has already collapsed. Therefore, the only potential concern is muktze, not dismantling. And Rabbi Shimon conforms to his standard line of reasoning, as he is not of the opinion that there is a prohibition of muktze, as it is taught in a baraita: If a wick in oil was lit before Shabbat, and it went out on Shabbat, the remainder of the oil in a lamp or in a bowl is prohibited for use, as it is muktze. And Rabbi Shimon permits one to use it. Consequently, Rabbi Shimon also permits one to take wood from the sukka.

מִי דָּמֵי? הָתָם אָדָם יוֹשֵׁב וּמְצַפֶּה אֵימָתַי תִּכְבֶּה נֵרוֹ, הָכָא אָדָם יוֹשֵׁב וּמְצַפֶּה אֵימָתַי תִּפּוֹל סוּכָּתוֹ?

The Gemara rejects this claim: Is it comparable? There, in the case of oil in a lamp, a person sits and anticipates when his lamp will be extinguished. It is clear to him that it will be extinguished, and he can safely assume that a certain amount of oil will remain in the lamp or the bowl. Here, however, can it be said that a person sits and anticipates when his sukka will fall? He cannot know ahead of time that his sukka will collapse.

אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק: הָכָא בְּסוּכָּה רְעוּעָה עָסְקִינַן, דְּמֵאֶתְמוֹל דַּעְתֵּיהּ עִלָּוַהּ.

Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak said: Here, we are dealing with a sukka that is not sturdy, as from yesterday, the Festival eve, one already had his mind on it. He thought it might collapse, and therefore he did not remove the possibility of using its wood from his mind.

וְשָׁוִין בְּסוּכַּת הֶחָג בֶּחָג שֶׁהִיא אֲסוּרָה, וְאִם הִתְנָה עָלֶיהָ — הַכֹּל לְפִי תְנָאוֹ. וּמִי מַהֲנֵי בַּהּ תְּנַאי?

§ The above baraita states: All agree with regard to the sukka that was built for the festival of Sukkot, that during the Festival it is prohibited to remove wood from it, but if one stipulated a condition with regard to it, it is all according to his condition. The Gemara asks: And is a condition effective with regard to it?

וְהָאָמַר רַב שֵׁשֶׁת מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא: מִנַּיִן לַעֲצֵי סוּכָּה שֶׁאֲסוּרִין כׇּל שִׁבְעָה — שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״חַג הַסּוּכּוֹת שִׁבְעַת יָמִים לַה׳״, וְתַנְיָא, רַבִּי יְהוּדָה בֶּן בְּתִירָא אוֹמֵר: מִנַּיִן שֶׁכְּשֵׁם שֶׁחָל שֵׁם שָׁמַיִם עַל הַחֲגִיגָה, כָּךְ חָל שֵׁם שָׁמַיִם עַל הַסּוּכָּה — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״חַג הַסּוּכּוֹת שִׁבְעַת יָמִים לַה׳״, מָה חַג לַה׳ — אַף סוּכָּה לַה׳.

But didn’t Rav Sheshet say in the name of Rabbi Akiva: From where is it derived that the wood of a sukka is prohibited to be used for any other use all seven days of the Festival? It is as it is stated: “The festival of Sukkot to the Lord, seven days” (Leviticus 23:34). And it is taught in a different baraita in explanation of this that Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira says: From where is it derived that just as the name of Heaven takes effect upon the Festival peace-offering, so too, does the name of Heaven take effect upon the sukka? The verse states: “The festival of Sukkot to the Lord, seven days” (Leviticus 23:34), from which it is learned: Just as the Festival offering is consecrated to the Lord, so too, the sukka is consecrated to the Lord. Since the wood of the sukka is compared to consecrated objects, how may one stipulate a condition with regard to it?

אָמַר רַב מְנַשְּׁיָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרָבָא: סֵיפָא אֲתָאן לְסוּכָּה דְעָלְמָא, אֲבָל סוּכָּה דְמִצְוָה — לָא מַהֲנֵי בַּהּ תְּנָאָה.

Rav Menashya, son of Rava, said: In the latter clause, where the stipulation is mentioned, we have arrived at the case of a regular sukka, a hut used throughout the year, not specifically for the Festival. With regard to such a sukka, one may stipulate to use the wood as he wishes; but as for a sukka of mitzva, used for the Festival, a condition is not effective with regard to it.

וְסוּכָּה דְּמִצְוָה לָא? וְהָתַנְיָא: סִכְּכָהּ כְּהִלְכָתָהּ וְעִטְּרָהּ בִּקְרָמִים וּבִסְדִינִין הַמְצוּיָּירִין, וְתָלָה בָּהּ אֱגוֹזִים שְׁקֵדִים אֲפַרְסְקִים וְרִמּוֹנִים וּפַרְכִּילֵי עֲנָבִים, יֵינוֹת שְׁמָנִים וּסְלָתוֹת וְעַטְרוֹת שִׁבֳּלִים — אָסוּר לְהִסְתַּפֵּק מֵהֶן עַד מוֹצָאֵי יוֹם טוֹב הָאַחֲרוֹן שֶׁל חַג. וְאִם הִתְנָה עֲלֵיהֶם — הַכֹּל לְפִי תְנָאוֹ.

The Gemara asks a question from a different angle: And is a condition not effective for a sukka of mitzva? But isn’t it taught in the Tosefta: In the case of a sukka that one roofed in accordance with its halakha, and decorated it with embroidered clothes and with patterned sheets, and hung on it nuts, almonds, peaches, pomegranates, and vines [parkilei], of grapes and glass containers filled with wine, oil, and flour, and wreaths of ears of corn for decoration, it is prohibited to derive benefit from any of these until the conclusion of the last Festival day. But if one stipulated a condition with regard to them whereby he allows himself to use them, it is all according to his condition. This shows that conditions are effective even with regard to a sukka of mitzva.

אַבָּיֵי וְרָבָא דְּאָמְרִי תַּרְוַיְיהוּ: בְּאוֹמֵר אֵינִי בּוֹדֵל מֵהֶם כׇּל בֵּין הַשְּׁמָשׁוֹת, דְּלָא חָלָה קְדוּשָּׁה עֲלַיְיהוּ. אֲבָל עֲצֵי סוּכָּה, דְּחָלָה קְדוּשָּׁה עֲלַיְיהוּ — אִתַּקְצַאי לְשִׁבְעָה.

The Gemara answers based on the opinion of Abaye and Rava, who both say that this is referring to a case where one says: I am not removing myself from them throughout twilight. In other words, he announces from the outset that he will not set them aside as sukka decorations, but rather he will use them for other purposes as well. In that case, no sanctity devolves upon them at all, and he may therefore use them throughout the Festival. However, as for the actual wood of a sukka, sanctity devolves upon it through the very construction of the sukka, and it has therefore been set aside from use for the entire seven days.

וּמַאי שְׁנָא מֵהָא דְּאִתְּמַר: הִפְרִישׁ שִׁבְעָה אֶתְרוֹגִים לְשִׁבְעַת הַיָּמִים, אָמַר רַב: כׇּל אַחַת וְאַחַת יוֹצֵא בָּהּ וְאוֹכְלָהּ לְאַלְתַּר. וְרַב אַסִּי אָמַר: כׇּל אַחַת יוֹצֵא בָּהּ וְאוֹכְלָהּ לְמָחָר!

The Gemara asks: And in what way is it different from that which was stated with regard to a different halakha: In the case of one who separated seven etrogim for each of the seven Festival days, one for each day, Rav said: He fulfills his obligation through each and every one of them when he recites the blessing over the lulav and etrog, and if he so desires he may eat it immediately after the blessing. And Rav Asi said: He fulfills his obligation through each one, and he may eat it the following day, as it retains its sanctity for the duration of that entire day. In any case, all agree that the sanctity of each etrog does not extend to the following day. If so, why does the sanctity of the sukka extend through all seven days?

הָתָם, דְּמַפְסְקוּ לֵילוֹת מִיָּמִים — כׇּל חַד וְחַד יוֹמָא מִצְוָה בְּאַפֵּי נַפְשֵׁיהּ הוּא. הָכָא, דְּלָא מַפְסְקוּ לֵילוֹת מִיָּמִים — כּוּלְּהוּ יוֹמֵי כַּחֲדָא יוֹמָא אֲרִיכְתָּא דָּמֵי.

The Gemara answers: There is a difference between an etrog and a sukka. There, with regard to an etrog, the nights are divided from the days, as the mitzva of etrog applies only during the day and not at night. This means that each and every day is its own mitzva, and therefore an item that is sanctified for one day is not necessarily sanctified for the following day. However, here, with regard to a sukka, where the nights are not divided from the days, as the mitzva of sukka applies at night as well, all seven days are considered as one long day. Throughout the Festival, there is no moment during which the sanctity of sukka leaves the wood; it leaves only at the conclusion of the Festival.